Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2025

Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts

| Content | Chemistry experiments - video | Physics experiments - video | Home Page - Chemistry and Chemists |

|

Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2025 Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts |

Qualitative Analysis (Identification) of Sulfuric Acid Volodymyr M. Viter |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

Qualitative Analysis (Identification) of Sulfuric Acid

In a chemist's work, situations often arise where labels fall off reagent bottles, or the inscriptions become illegible. Occasionally, the label may not match the contents. As a result, one might end up with a bottle containing an unknown liquid or powder.

Качественный анализ (идентификация) серной кислоты Classical chemistry literature advises discarding such reagents without hesitation. However, in practice, the reality is different. Reagents are expensive, and budgets are often tight. Even with sufficient funding, certain reagents may be unavailable or require long delivery times. These challenges could be compounded by exceptional circumstances, such as the current war in our country. Practicing chemists, therefore, don't follow the advice to discard unlabeled reagents blindly. Instead, they attempt to identify them. For instance, I came across a case online where someone posted: "Unknown bottles of some sort of acid.

We are clearing out my late grandparents' garage and came across these two bottles. Could anyone identify what they contain based on the pictures? The labels are badly damaged, but one of them says "acid," and that's all we can make out. The bottles are glass with plastic screw caps, each likely holding around 2 liters. Any advice on how to handle them would be appreciated. Thanks for your time."

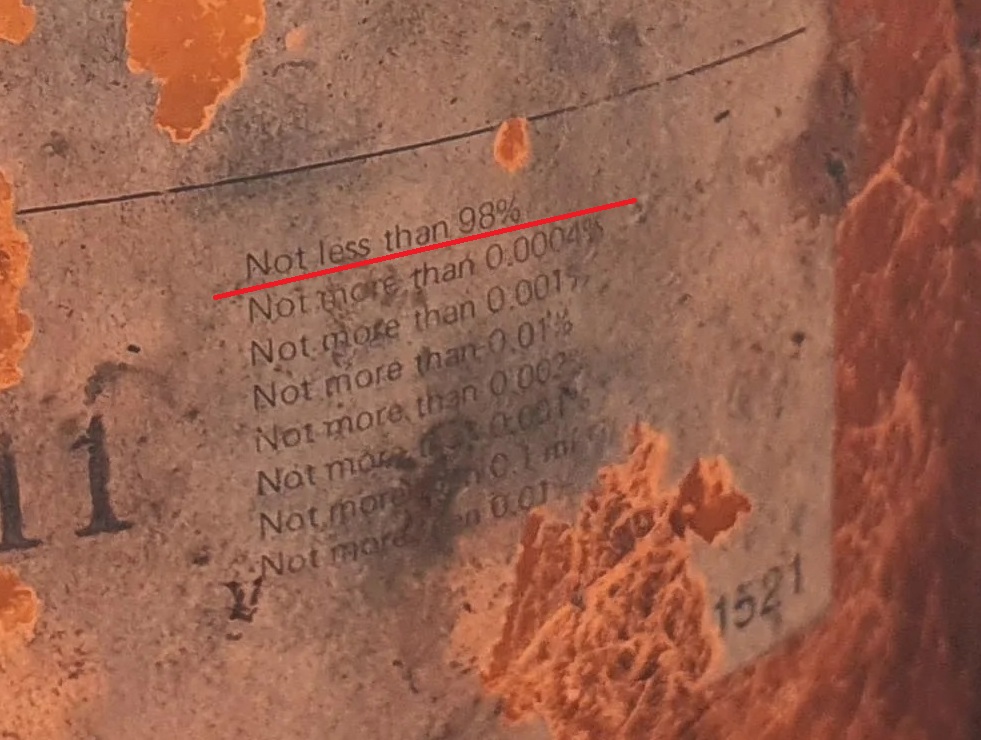

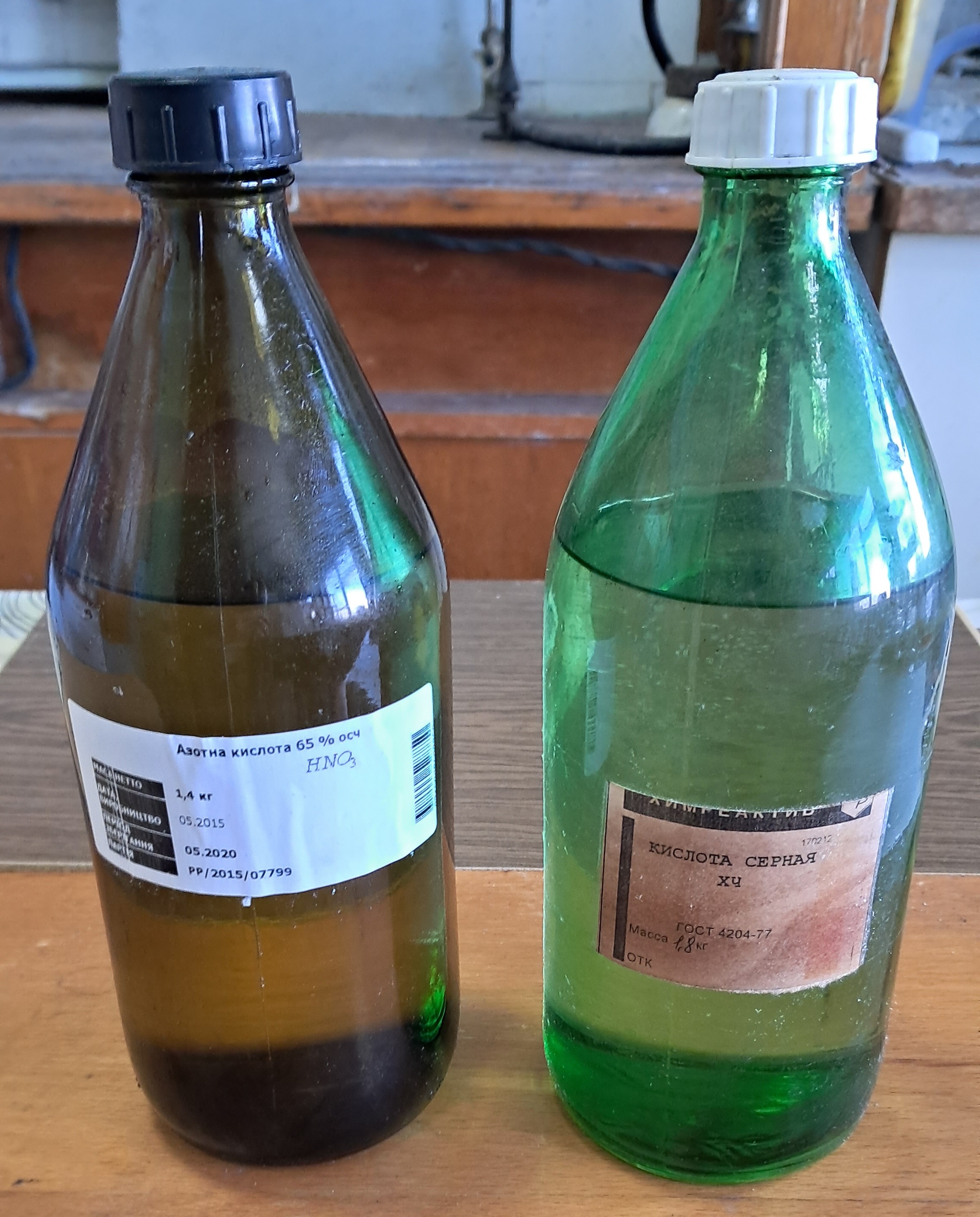

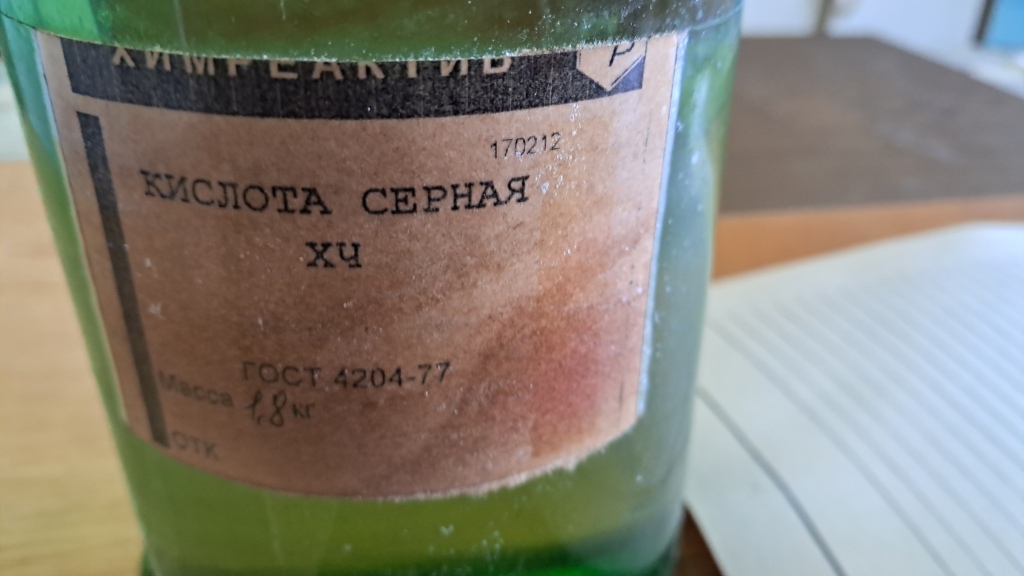

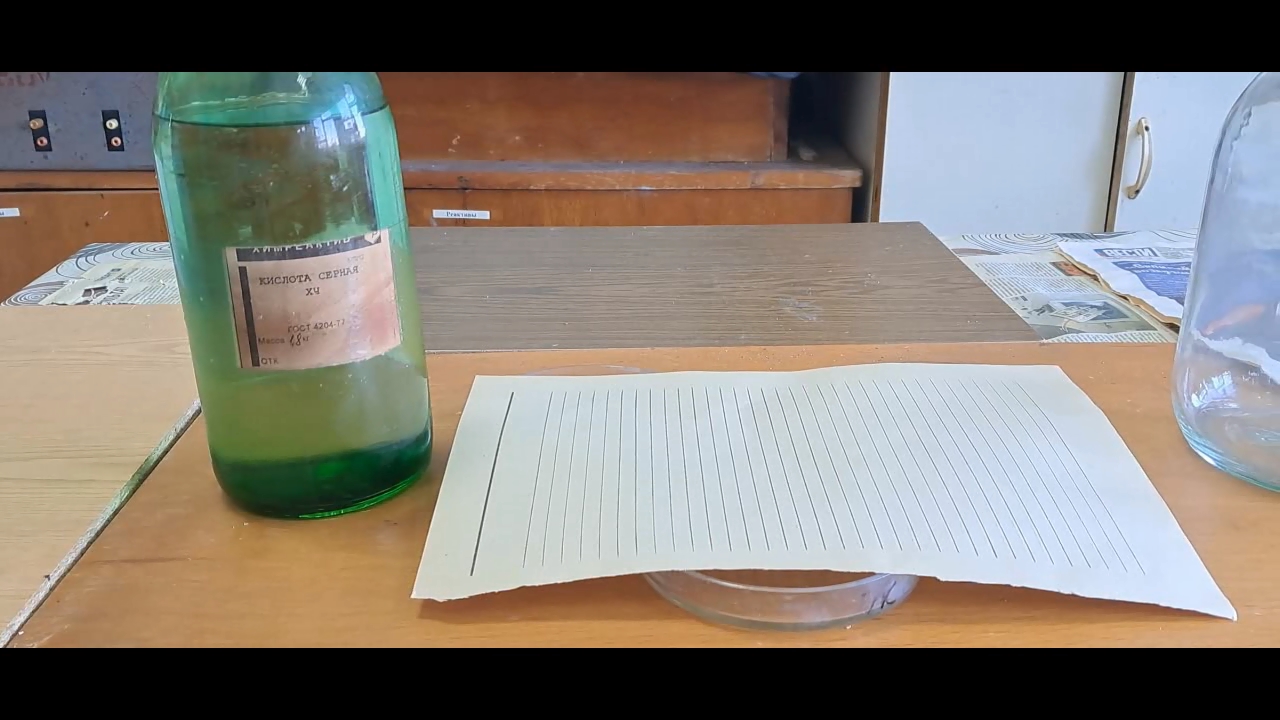

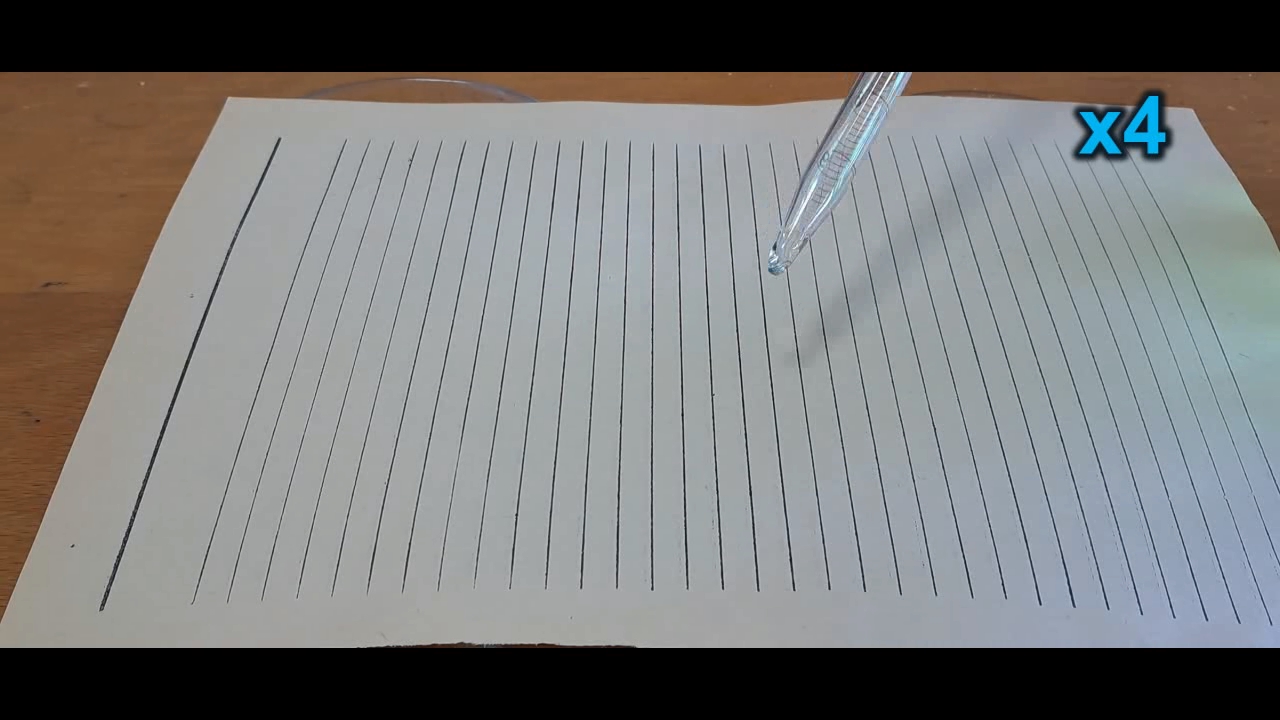

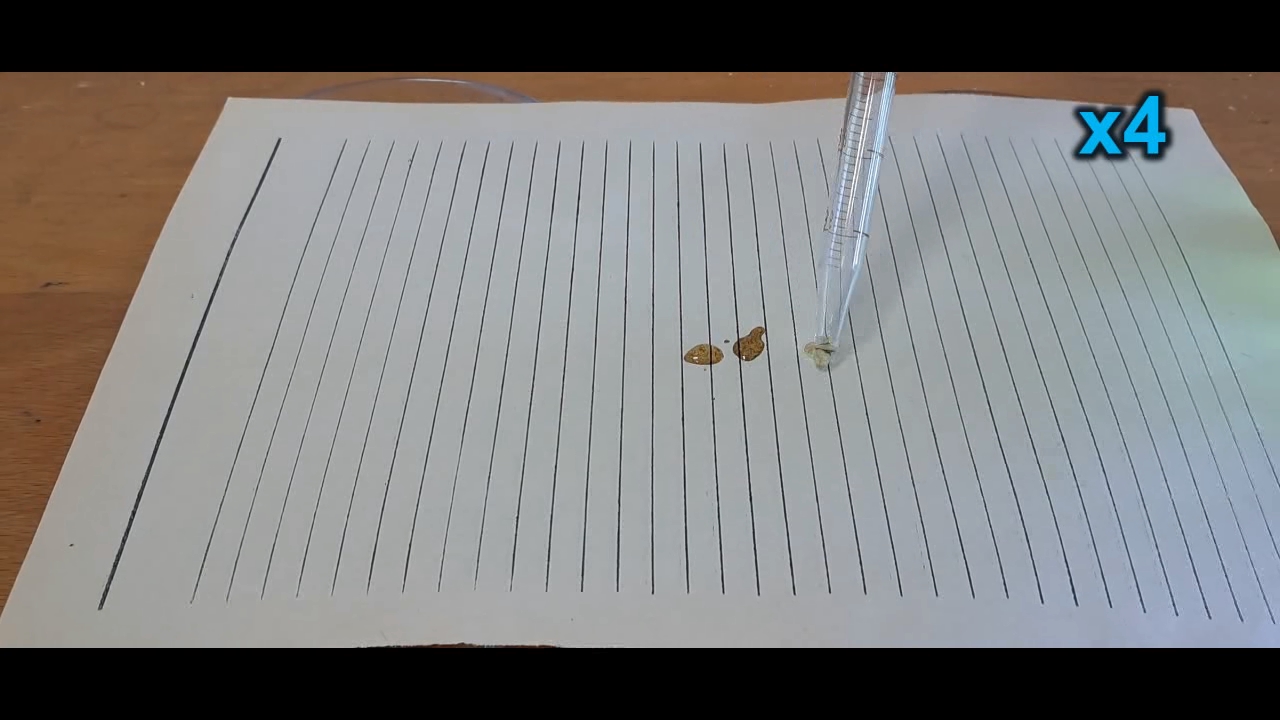

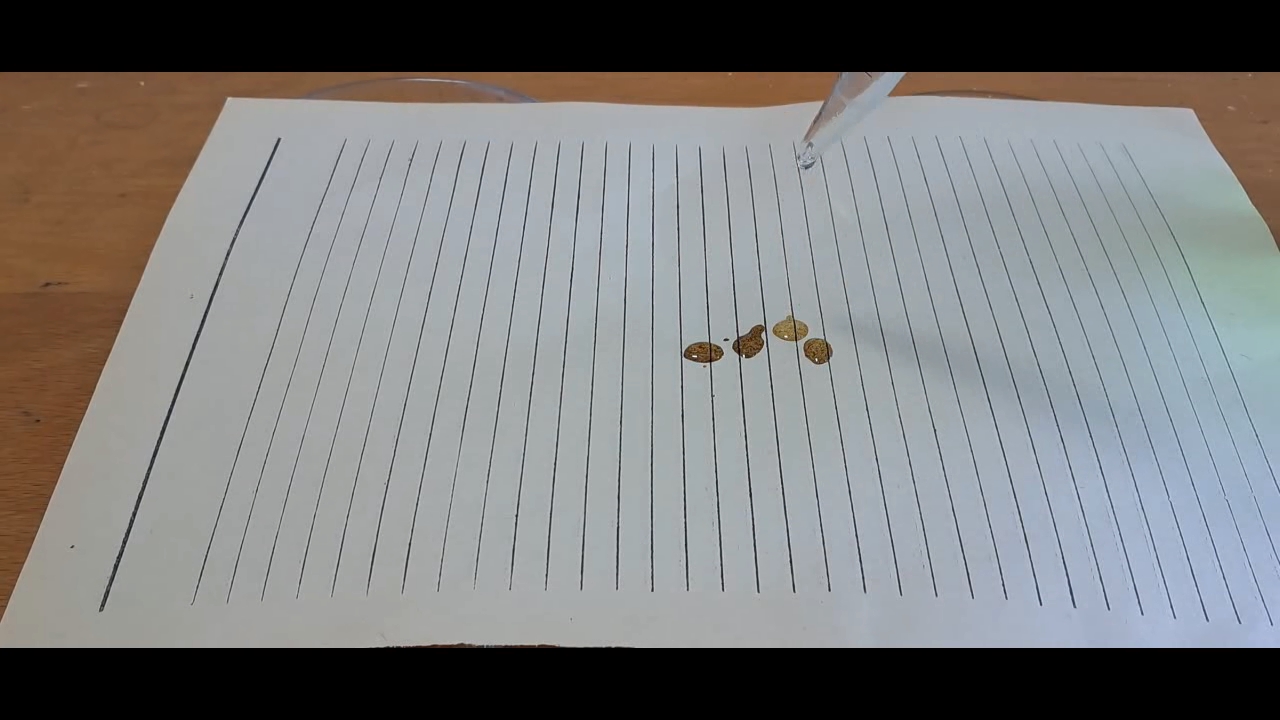

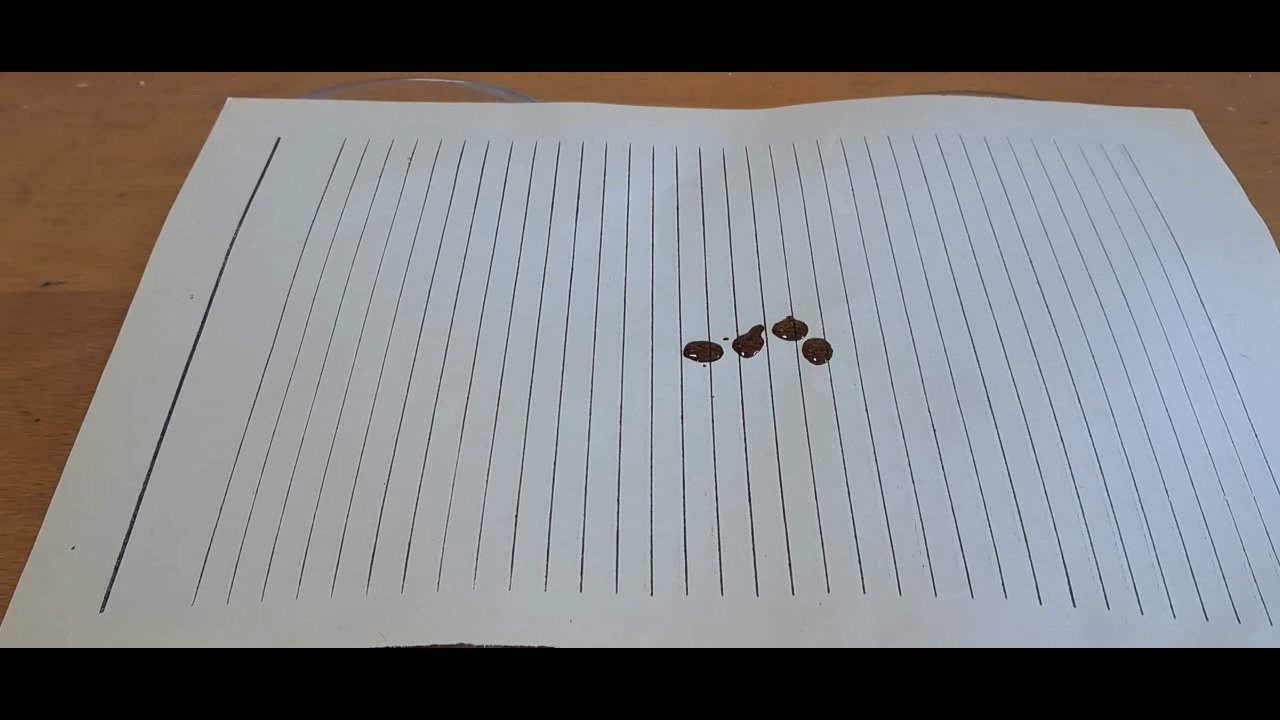

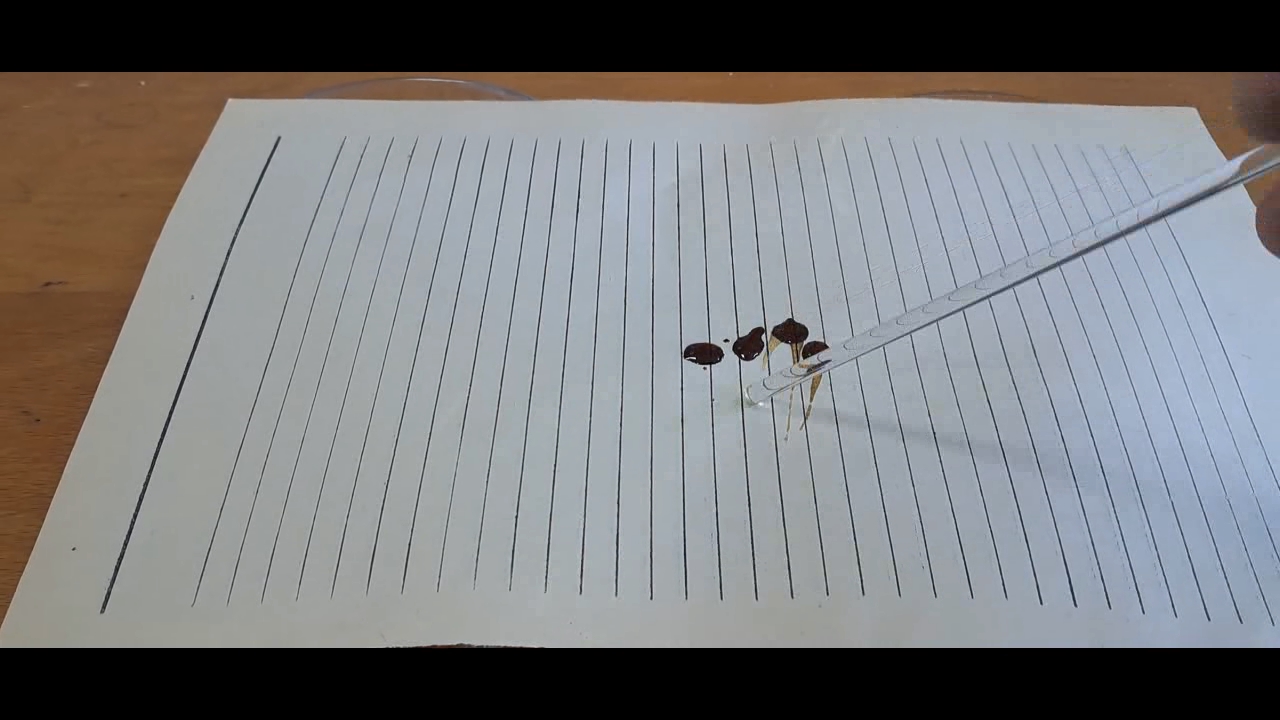

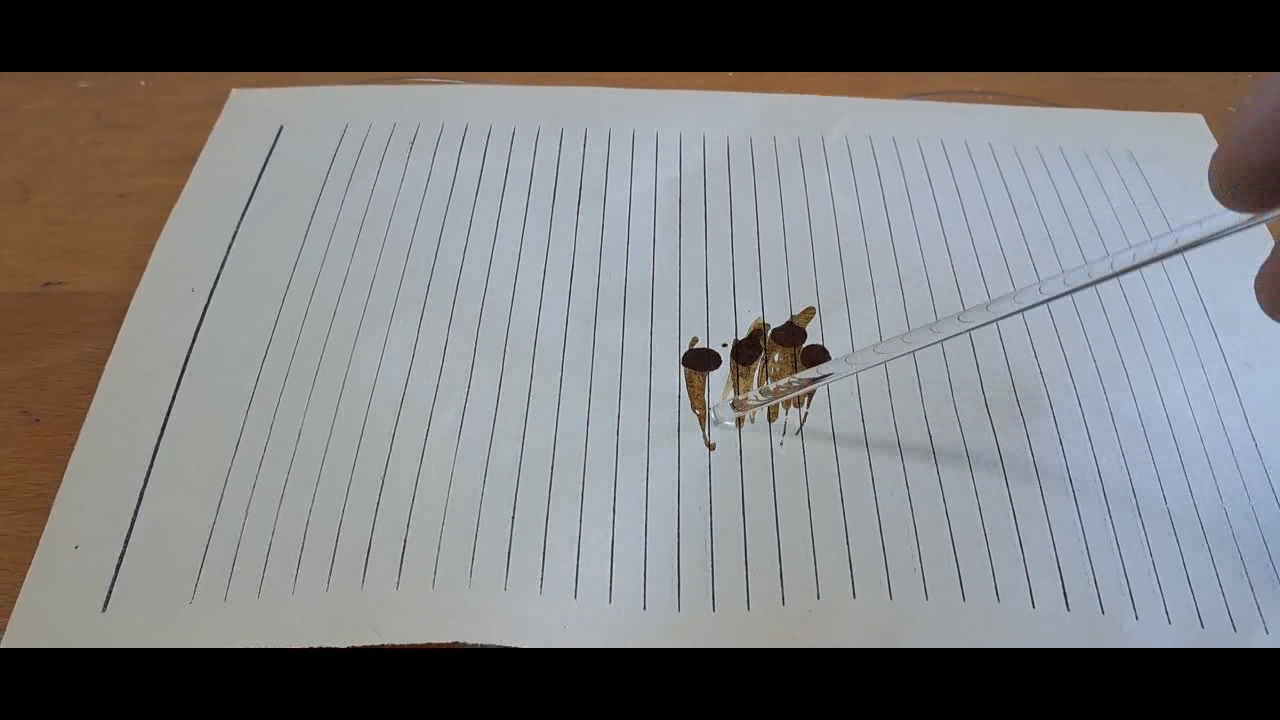

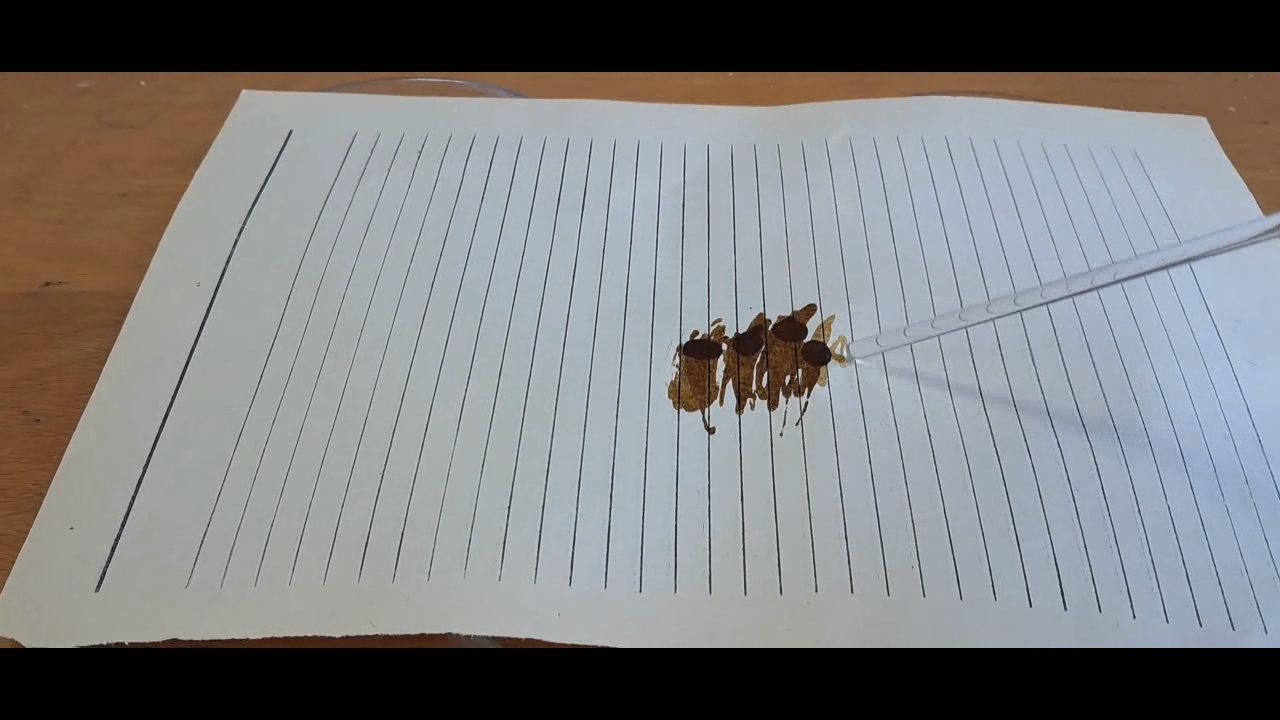

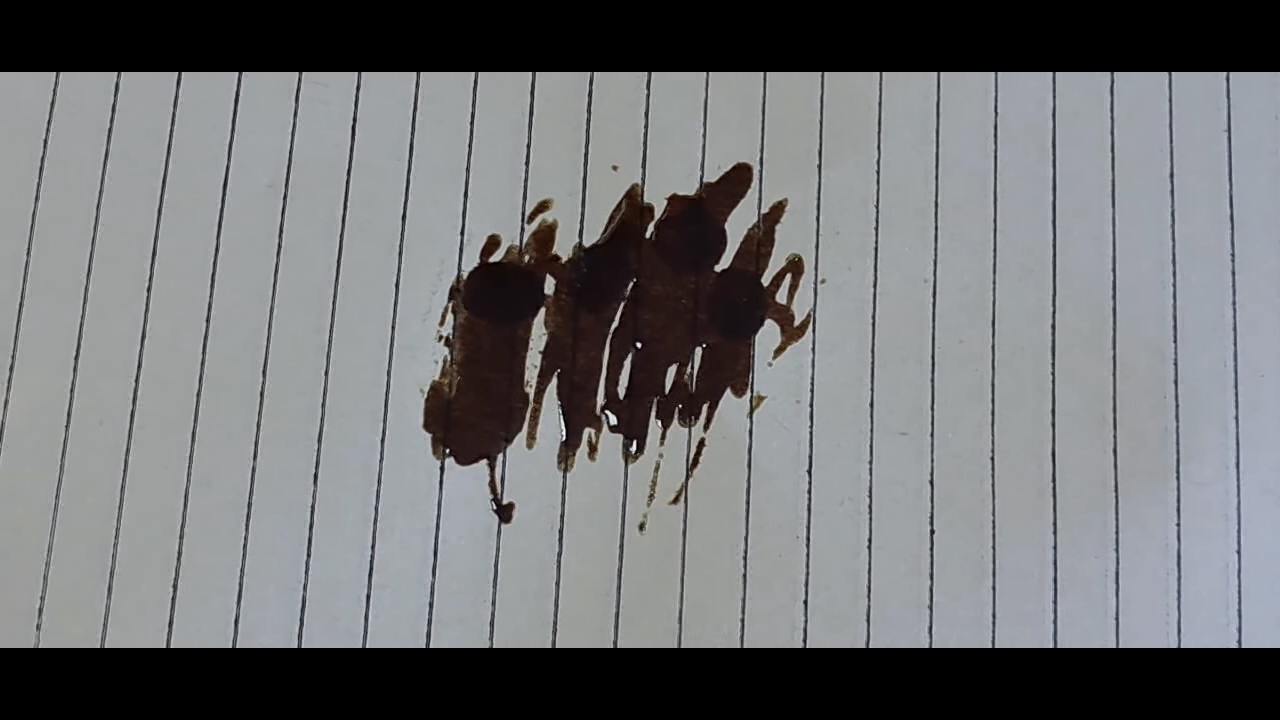

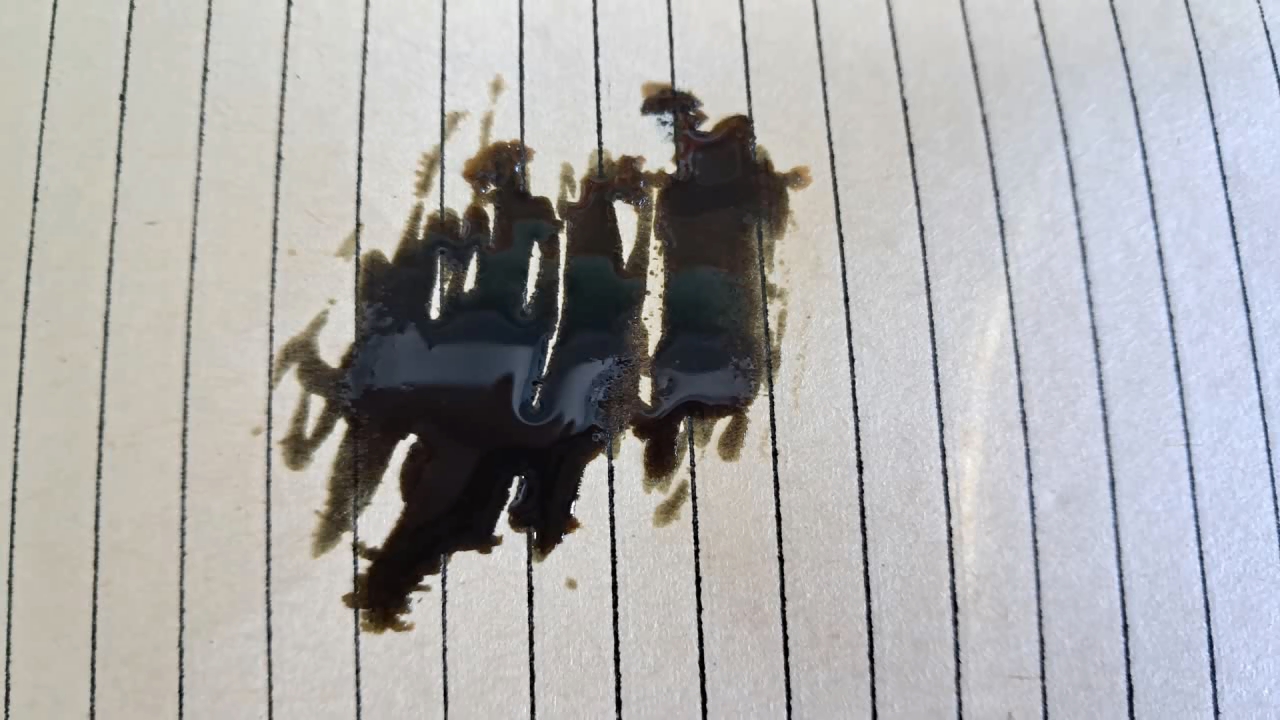

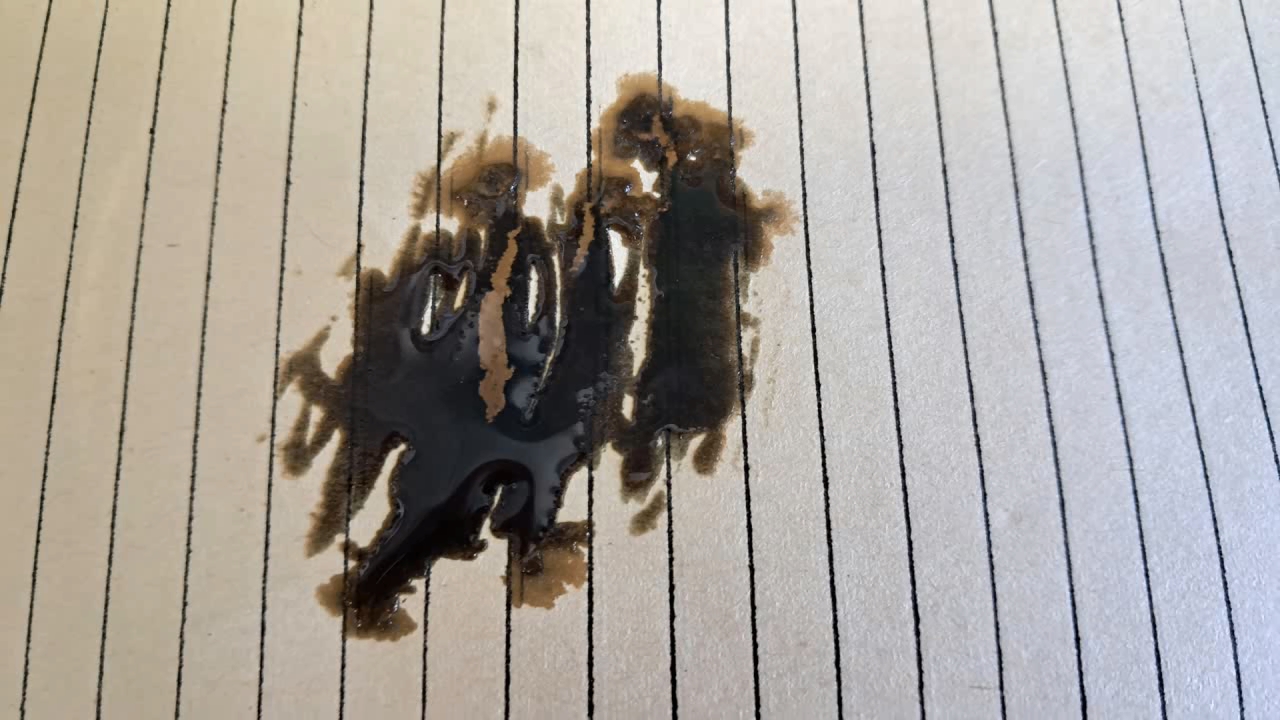

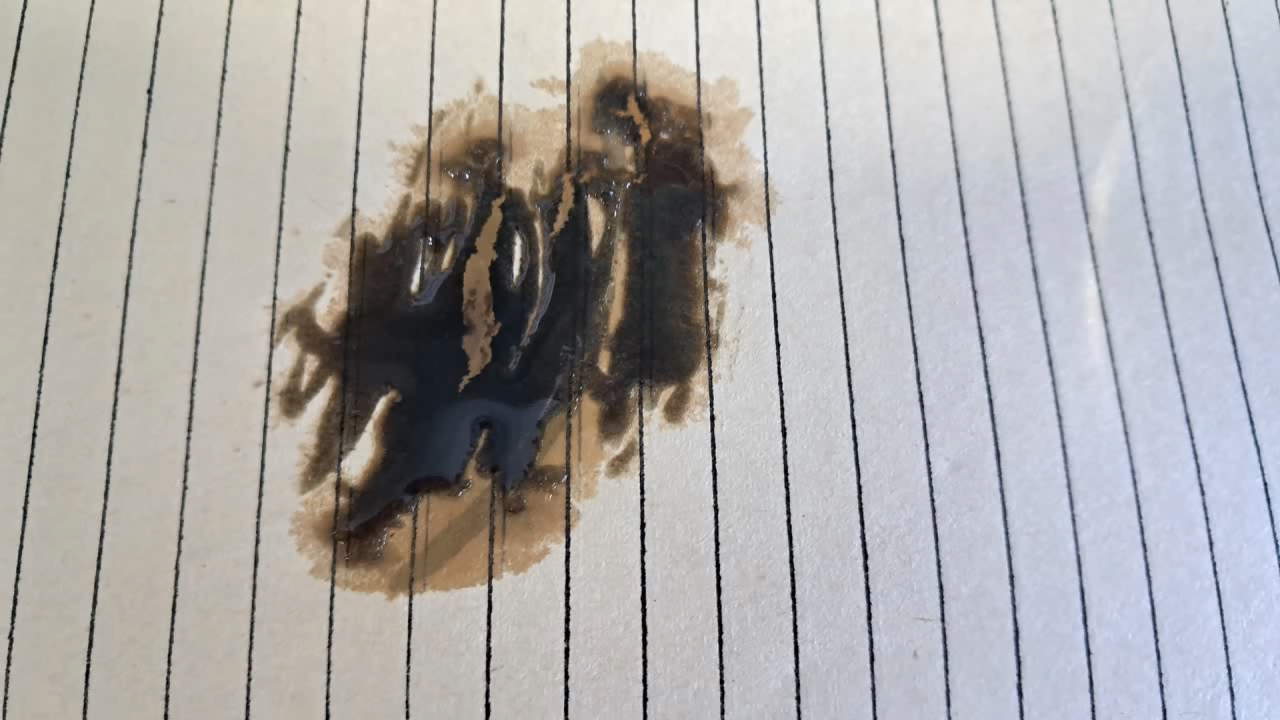

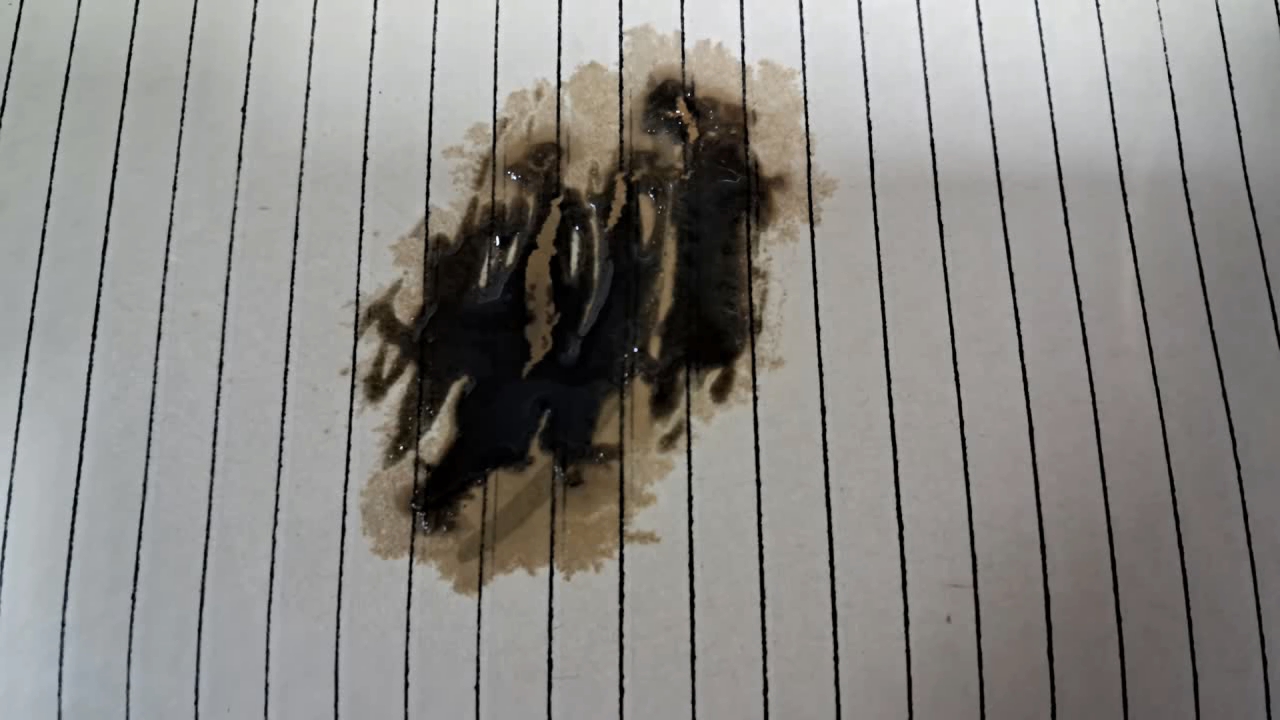

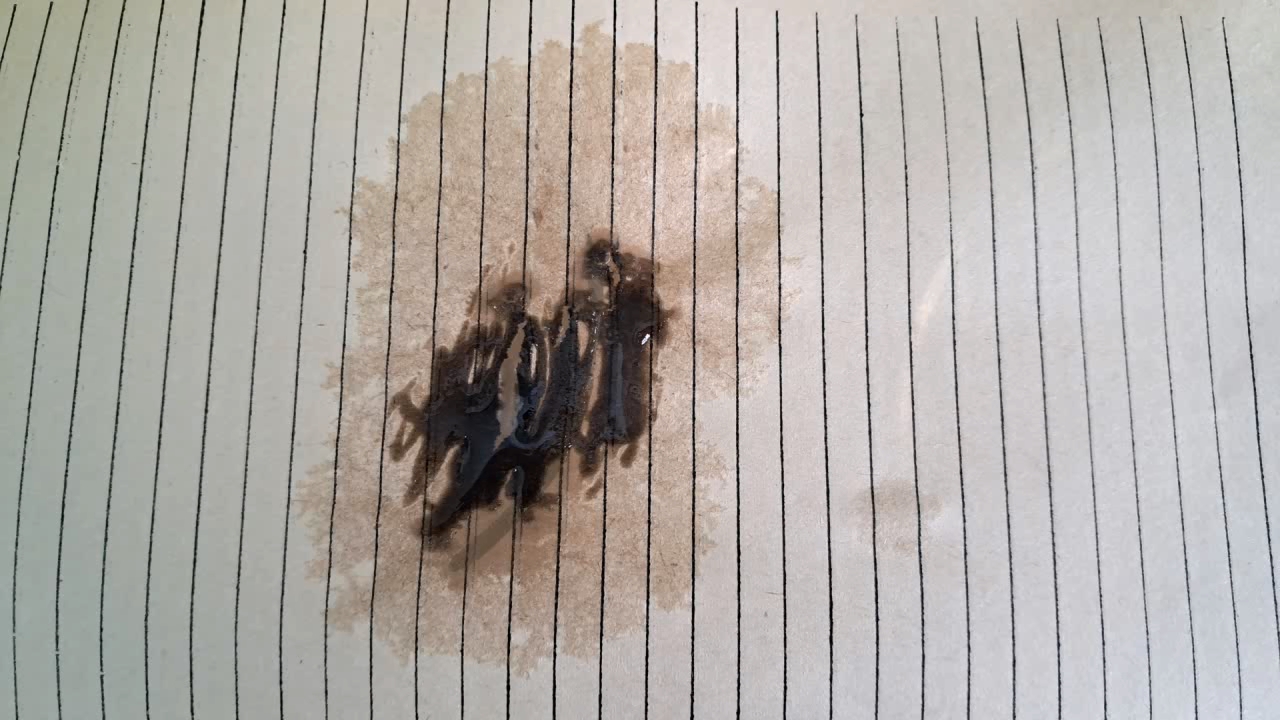

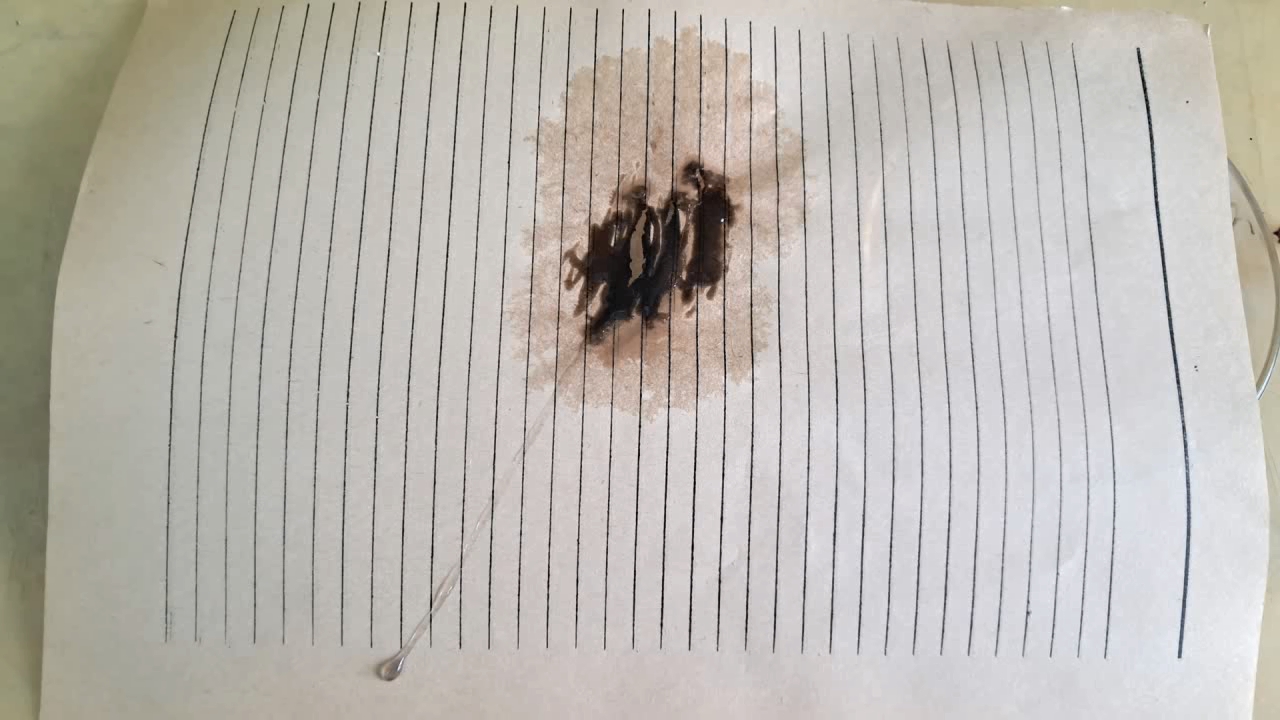

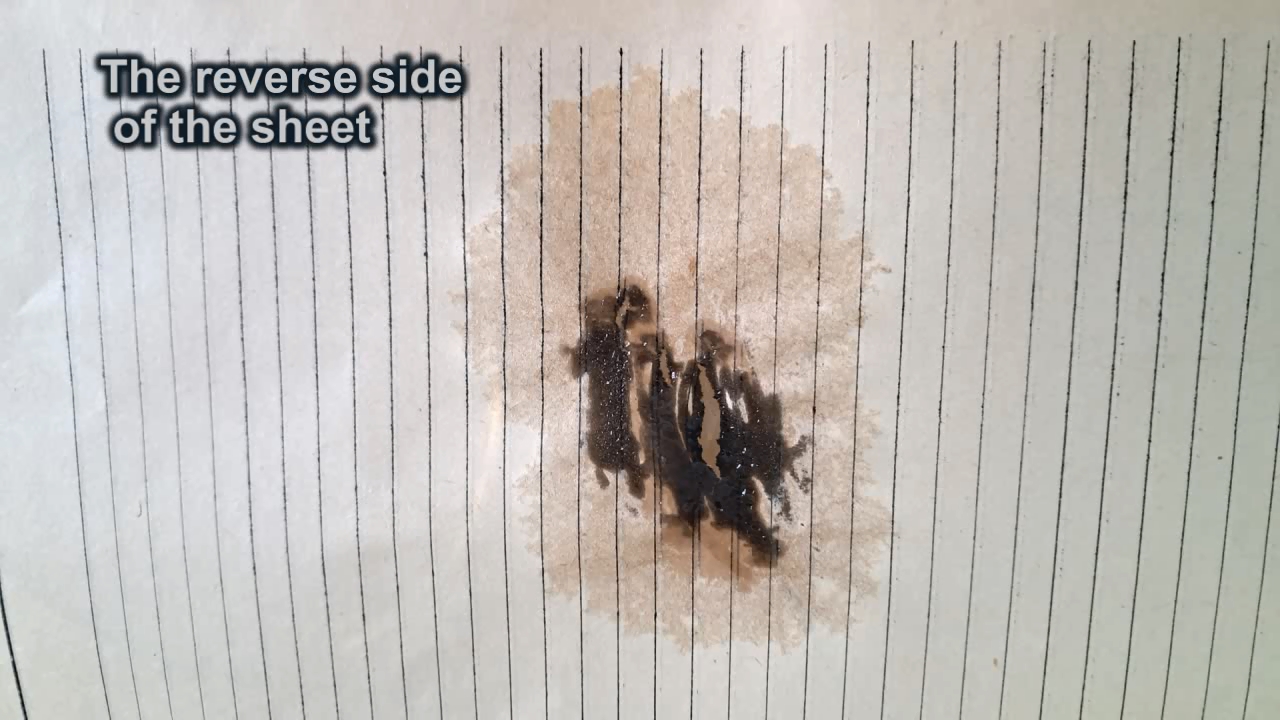

The photographs showed two bottles with deteriorated labels. On one label, the word "acid" was visible, along with the phrase "Not less than 98%." This suggests that the bottles most likely contain sulfuric acid.  However, a colleague objected pointing out a similar experience: "I was once asked to identify the acid in an unmarked bottle. The liquid was heavy, viscous, and odorless. Since only sulfuric and phosphoric acids are used at our galvanic plant, I tested it using a straw. It turned out to be phosphoric acid, as it didn't char the straw. Commercial available phosphoric acid usually has a concentration of 85%, but higher concentrations are possible. At 98% concentration, phosphoric acid is crystalline at room temperature but can remain liquid if supercooled. Despite the clues, it is essential to perform qualitative tests to confirm the compound's identity, as damaged labels may not match the bottles' contents. Meanwhile, I encountered a similar issue. The label on a bottle containing liquid read: "Concentrated sulfuric acid, chemically pure." The label was old, as it was written in Russian - nowadays, labels are typically in Ukrainian or English. The liquid was heavy, and while the label was intact and legible, I wasn't confident in its correctness. It was possible that a mistake had occurred (e.g., phosphoric acid or tetrachloromethane had been poured into the sulfuric acid bottle, but the label wasn't updated). Even deliberate sabotage couldn't be ruled out. If predecessors were treated unfairly, they might have done something like this before being dismissed. Does this sound paranoid? Perhaps, but I've encountered such situations before. To identify the sulfuric acid, I used the method described earlier, substituting paper for the straw. Initially, I considered using white printer paper, but I remembered that it contains chalk. Instead, I cut a yellowish page from an old laboratory workbook. The first challenge was opening the bottle - its cap was jammed, and I struggled to unscrew it. This reminded me of a joke: "On a urine test result form, the lab technician wrote: 'I couldn't open the jar!'." After finally opening the bottle, I applied a few drops of the liquid to the paper. The paper immediately turned brown at the contact points, and the stains darkened quickly. Using a glass rod, I spread the acid over a larger area. Within minutes, the stains turned dark brown. Although the result was already clear, I continued observing. A light brown halo formed around the dark stains, significantly exceeding the area of the stains themselves. Eventually, holes appeared at the center of the stains. Phosphoric acid does not affect paper this way. Conclusion: The bottle contained concentrated sulfuric acid. |

Qualitative Analysis (Identification) of Sulfuric Acid |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How Fungi Ate Radioactive Graphite Good Chemist |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

Background: The Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant Accident

Many years ago, a colleague told me a truly incredible story. But first, I must recall the well-known circumstances under which it all happened.

As you may know, two materials are primarily used to slow down neutrons in nuclear reactors: heavy (deuterium) water or high-purity graphite. The reactors at the nuclear power plant (NPP) in the Ukrainian city of Chornobyl utilized graphite as a neutron moderator. However, these reactors were designed with several serious flaws, making them unreliable and prone to accidents. The plant was built near Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. The potentially catastrophic consequences of an accident at such a plant could have been foreseen well before its construction. However, at that time, Ukraine was part of the USSR, and the Moscow leadership showed little regard for human life - neither its own citizens nor those of other nations. In fact, the primary purpose of the four reactors at this facility was not to generate electricity but to produce weapons-grade plutonium. The electricity produced by the reactors was a useful byproduct, but the plant's main goal was to supply plutonium for nuclear weapons, which were meant to support the USSR's strategy of global intimidation. The design of the Chornobyl reactors was guided by the goal of maximizing plutonium production, and this design logic ultimately contributed to the disaster. On the night of April 26, 1986, a combination of design flaws and gross operator errors led to an explosion in the reactor of the fourth power unit. This event became the largest nuclear accident in human history. Unlike the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, there was no towering "mushroom cloud," no shock wave leveling buildings, and no thousands of people vaporized by radiation. Only the reactor itself and the building surrounding it were destroyed. Nevertheless, the Chornobyl accident caused devastation comparable to that of a nuclear weapon detonation. For comparison, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima contained 64 kg of uranium, while the bomb dropped on Nagasaki contained 6.2 kg of plutonium. By contrast, a nuclear reactor can contain hundreds of tons of nuclear fuel. According to an article from "Radio Liberty" (2021): "According to official government data, up to 200 tons of nuclear fuel and fuel-containing materials remain in the fourth power unit - that is, 95% of the amount that was loaded into the reactor at the time of the 1986 accident." Let's calculate how much nuclear fuel and its fission products were released from the reactor during the explosion. At the time of the accident, the total amount of nuclear fuel in the reactor was: 200/0.95 = 210.5 tons The amount of fuel and fission products ejected during the explosion was: 210.5*(1-0.95) = 10.5 tons This means that approximately 10.5 tons of nuclear fuel and its fission products were released into the environment. In terms of mass, this corresponds to 165 times the amount of nuclear material used in the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima [1]. The release of such a vast amount of nuclear fuel and its fission products from the reactor caused large-scale, long-term radioactive contamination, far more severe than that seen in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Although 38 years have passed since the accident, the exclusion zone around the plant - known as the "Chornobyl 30-kilometer zone" - remains in place, with strict limits on human presence. When the reactor exploded, graphite blocks used as neutron moderators were also ejected. Soldiers — most of whom were young — were forced to collect this radioactive graphite with shovels, often without proper protection from radiation. Tragically, many of them later died from radiation-related illnesses. The Chornobyl accident is widely regarded as one of the key factors that contributed to the collapse of the USSR. The disaster exposed the inadequacy of Soviet propaganda and revealed to ordinary citizens the harsh reality of how little their lives were valued by the state. Of course, the soldiers were unable to collect all the radioactive graphite, as pieces of the graphite blocks had been scattered over a vast area. Despite the hazards, people continue to work in the Chornobyl zone today, including scientists, maintenance personnel, and security staff. Additionally, there are individuals who engage in "illegal tourism" within the zone. These people call themselves "stalkers." Stalkers enter the zone unlawfully by avoiding checkpoints, often traveling through forests, taking photographs, and collecting various items as souvenirs. For those who visit the exclusion zone legally, access is strictly controlled. Visitors must pass through security checkpoints where their documents are verified, their belongings inspected, and dosimetric control (radiation screening) is performed before they exit the zone. This is where our story begins. Fungi Ate Radioactive Graphite

Scientists decided to study several samples of radioactive graphite that had been ejected from the reactor during the accident. One of the samples was brought to the laboratory and temporarily placed in a jar of water (to shield it from ionizing radiation). The jar was then stored inside a safe.

After some time, the scientists opened the safe - and to their astonishment, the graphite was gone. It had completely disappeared. Instead, they found the jar filled with black fungi! In other words, the fungi had "eaten" the radioactive graphite. Intrigued, they attempted to replicate the experiment using non-irradiated graphite. This time, however, the fungi refused to consume it. Several graphite samples from the Chornobyl accident site remained available, and it would have been logical to continue the research. However, an inspection commission arrived at the institute for a review. Fearing discovery, one of the employees panicked and decided to hide the radioactive graphite samples. Here's the context: although the scientists worked legally in the Chornobyl exclusion zone, the graphite samples had been obtained illegally from "stalkers." The scientists had exchanged alcohol for the samples. This was done because obtaining official permits for sample collection and transport was extremely difficult - if not outright impossible - due to bureaucratic red tape. Although the "evil empire" (the USSR) had long since collapsed, its legacy of bureaucracy and corruption remained. When people leave the Chornobyl exclusion zone, they are required to go through dosimetric control, where both individuals and their luggage are checked for radiation. To smuggle the samples past security, one of the employees devised a clever strategy. He carried a radioactive calibration source (used to test dosimeters) and placed it near the graphite samples in his bag. When the guard detected radioactivity in the luggage, the employee calmly showed the calibration source and the official documents authorizing its use. In this way, the samples were successfully smuggled out. Once the samples were brought to the institute, they were hidden for safety reasons. The presence of illegal radioactive materials could result in serious legal consequences for the staff. When the commission arrived, one of the employees grew anxious. If the commission discovered the graphite, he could face imprisonment. One might wonder if someone had tipped off the commission, reporting that the institute was conducting unauthorized research with radioactive materials. But it turns out this was not the case. The commission had no knowledge of the samples' existence, and as a result, no issues arose. Unfortunately, the employees never managed to locate the hidden graphite samples again. It is possible that the samples are still in the institute's storage facility - unless, of course, fungi have already found them and "eaten" them. How did the scientists plan to publish the results without official permission to collect samples? This remains a mystery. Since I do not know the answer, I will not speculate. Finally, I would like to offer the following explanation for the strange "graphite-fungi interaction." The fungi "ate" irradiated graphite but refused to consume unirradiated graphite. This may be due to the presence of radiation-induced defects in the graphite structure, which could have made it more chemically "accessible" to the fungi. Of course, this is only a hypothesis. To draw firm conclusions, a series of controlled experiments with multiple samples would be required, as a single result is not sufficient to establish a scientific theory. __________________________________________________ 1 The uranium used as fuel in nuclear power plants has a significantly lower enrichment level (the ratio of uranium-235 to the sum of the isotopes: uranium-238 and uranium-235) than the uranium used in atomic bombs, but the percentage of uranium-235 in the fuel is still significant. In addition, uranium-238 absorbs neutrons during reactor operation, undergoing a series of nuclear reactions to form plutonium-239 (another type of nuclear fuel) and, in some cases, americium. Уран, который используется на АЭС в качестве топлива, имеет существенно более низкую степень обогащения (соотношение урана-235 к сумме изотопов: уран-238 и уран-235), чем уран, используемый для атомных бомб, но содержание урана-235 в топливе все равно значительное. Кроме того, уран-238 поглощает нейтроны во время работы реактора, претерпевая ряд ядерных превращений с образованием плутония-239 (еще одного вида ядерного топлива) и, в некоторых случаях, америция. |

|

Как грибы радиоактивный графит съели

Предыстория. Авария на Чернобыльской атомной станции

Много лет назад коллега рассказал просто невероятную историю. Но сначала я должен напомнить известные обстоятельства, при которых все это произошло.

Как вы, вероятно, знаете, для замедления нейтронов в ядерных реакторах используется в основном два материала: тяжелая (дейтериевая) вода или высокочистый графит. В реакторах атомной электростанции (АЭС) в украинском городе Чернобыль использовался графит. Реакторы на данной электростанции были спроектированы с рядом серьезных ошибок конструкции. Поэтому атомные реакторы данного типа были ненадежны и склонны к авариям. Саму станцию построили вблизи от столицы Украины, города Киева. Фатальные последствия аварии на такой станции можно было предвидеть задолго ДО ее строительства. Однако тогда Украина входила в состав СССР, а московское руководство никогда не ценило жизнь людей: ни своих, ни чужих. Фактически все четыре реактора данной станции предназначались не для производства электроэнергии, а для наработки оружейного плутония. Электроэнергия, вырабатываемая реакторами, служила бонусом, но основной целью данной атомной станции был плутоний, необходимый, чтобы запугивать весь мир ядерным оружием. Именно получение максимального количества плутония послужило критерием, на основе которого была разработана конструкция ректоров в Чернобыле. Из-за ошибок конструкторов и грубейших ошибок персонала станции реактор четвертого энергоблока взорвался в ночь на 26 апреля 1986 года. Произошла крупнейшая атомная авария в истории человечества. Не было ни огромного "атомного гриба", как в Хиросиме и Нагасаки в 1945 г, ни тысяч людей, превращенных излучением в пепел, ни огромной ударной волны, которая сметала здания. Разрушены были только сам реактор и окружающее его здание. Однако авария в Чернобыле причинила вред не меньший, чем прямой удар ядерным оружием. В бомбе, сброшенной на Хиросиму, было 64 кг урана; а в бомбе, примененной в Нагасаки, находилось 6.2 кг плутония. Зато в реакторе АЭС могут находиться сотни тонн ядерного топлива. Приведу цитату из статьи "Радио Свобода" (2021): "По официальным правительственным данным, в четвертом энергоблоке остается до 200 тонн ядерного топлива и топливосодержащих материалов: то есть 95% того количества, которое было загружено в реактор на время аварии 1986 года." Проведем простой расчет, сколько топлива и продуктов его деления было выброшено за пределы реактора: В реакторе находилось ядерного топлива (на момент аварии): 200/0.95 = 210.5 т. Было выброшено ядерного топлива и продуктов его деления: 210.5*(1-0.95) = 10.5 т. По массе это в 165 раз больше, чем количество ядерного материала в бомбе, сброшенной на Хиросиму [1]. Выброс из реактора такого огромного количества топлива и продуктов его деления вызвал масштабное и длительное радиоактивное заражение, гораздо более серьезное, чем было в Хиросиме и Нагасаки в 1945 г. С момента аварии прошло уже 38 лет, но до сих пор вокруг станции существует зона отчуждения ("Чернобыльская 30-километровая зона"), пребывание людей в которой строго ограничено. При взрыве реактора разлетелись и графитовые блоки. Солдат - молодых мальчиков - заставили собирать выброшенный из реактора графит лопатами без надлежащих средств защиты от радиации. Многие из них впоследствии погибли от болезней, вызванных облучением. Аварию на Чернобыльской АЭС по праву считают одной из основных причин распада СССР, поскольку завеса пропаганды ослабла и люди осознали, что с ними обращаются, как с животными. Разумеется, солдаты собрали далеко не весь радиоактивный графит, поскольку куски графитовых блоков разбросало по значительной площади. Несмотря на опасность, в Чернобыльской зоне работают люди: ученые, обслуживающий персонал, охрана и т.д. Есть также личности, которые занимаются "нелегальным туризмом" в Чернобыльскую зону. Сами себя они называют "сталкеры". Сталкеры проникают в зону нелегально (минуя контрольные пункты), путешествуют, фотографируют, собирают разные предметы. Если вы приезжаете в зону легально, вам необходимо пройти через пропускные пункты. Охрана проверяет документы и осматривает вещи, а при выезде ведется дозиметрический контроль. Здесь и начинается наша история. Грибы съели радиоактивный графит

Ученые решили исследовать несколько образцов радиоактивного графита, выброшенного из реактора во время аварии. Один из образцов принесли в лабораторию, временно поместили в банку с водой (для защиты от ионизирующего излучения), банку поставили в сейф. Когда через время они открыли сейф, то обнаружили, что графит в банке ОТСУТСТВОВАЛ. Графит исчез полностью - вместо него в банке был черный грибок! Другими словами, грибы "съели" графит, причем радиоактивный!

Попробовали провести аналогичный эксперимент с таким же графитам, но необлученным радиацией. Грибы употреблять этот графит в пищу отказались! Оставалось еще несколько образцов графита с места аварии, логичным было бы продолжить исследования. Однако в институт пришла комиссия с проверкой. Один из сотрудников испугался, запаниковал и спрятал образцы радиоактивного графита подальше. Дело в том, что ученые работали Чернобыльской зоне легально, однако, образцы графита они получили от "сталкеров", выменяв их на спирт. Разумеется, это было незаконно. Так пришлось поступить потому, что оформление официальных разрешений на отбор и транспортирование образцов было очень сложным, почти невозможным. Хотя "империя зла" (СССР) давно распался, бюрократия и коррупция остались. При вывозе из зоны необходимо было пройти дозиметрический контроль, в т.ч. и багажа. У одного из сотрудников был радиоактивный источник, предназначенный для калибровки дозиметров, он поместил его в сумку возле образцов графита. Когда охранник заметил, что багаж радиоактивен, сотрудник предъявил ему калибровочный источник и документы на него. Так удалось вывезти образцы. Разумеется, образцы пришлось прятать и после того, как они были доставлены в институт. Поэтому один из сотрудников и забеспокоился. Если бы комиссия обнаружила у него этот графит, ему угрожало тюремное заключение. Я поинтересовался: возможно, кто-то написал донос, что в институте ведутся нелегальные исследования с радиоактивными веществами? Оказывается, что нет. Комиссия не подозревала о существовании этих образцов, поэтому никаких проблем не возникло. К сожалению, потом эти спрятанные образцы сотрудники так и не смогли найти. Графит до сих пор лежит где-то в укромном месте на складе, если до образцов не добрались грибы и не съели их. Как ученые планировали публиковать результаты, не имея официального разрешения на отбор образцов? Этого я не знаю, поэтому не буду фантазировать. В конце я хотел бы предложить следующее объяснение странного "взаимодействия графита и грибов". Грибы "съели" облученный графит, но отказались потреблять необлученный графит. Это может быть связано с наличием радиационных дефектов в структуре графита, которые могли сделать его химически "более доступным" для грибов. Конечно, это только гипотеза. Чтобы сделать надежные выводы, необходимо провести серию контролируемых экспериментов со многими образцами. Единичного результата для создания научной теории недостаточно. |

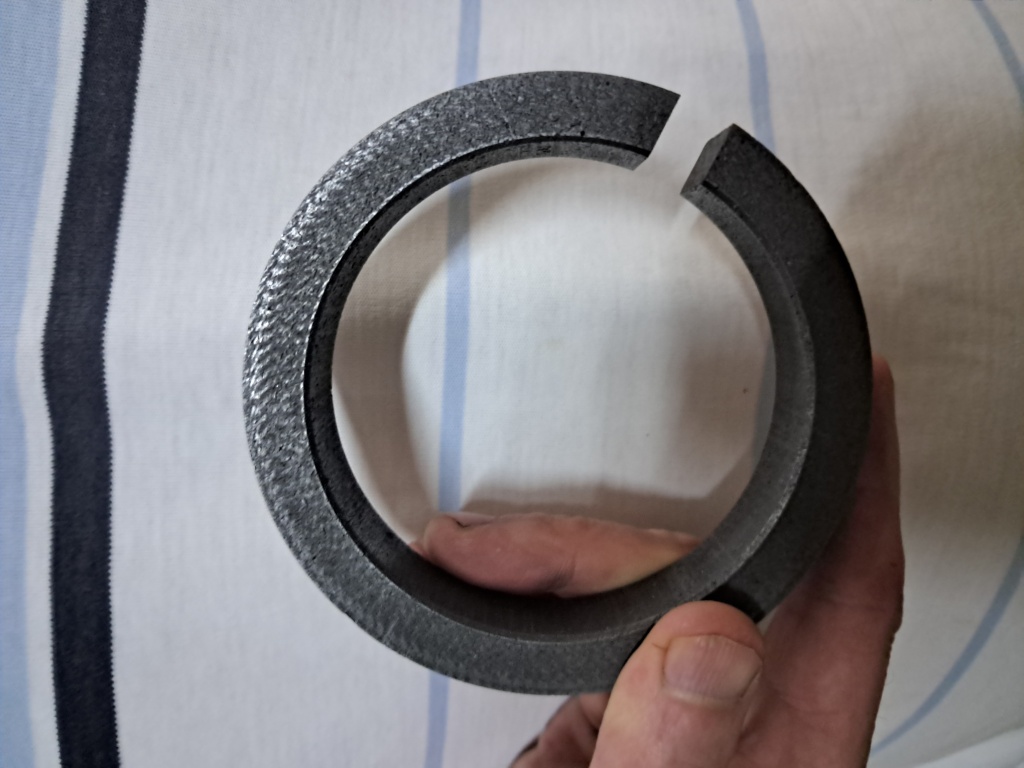

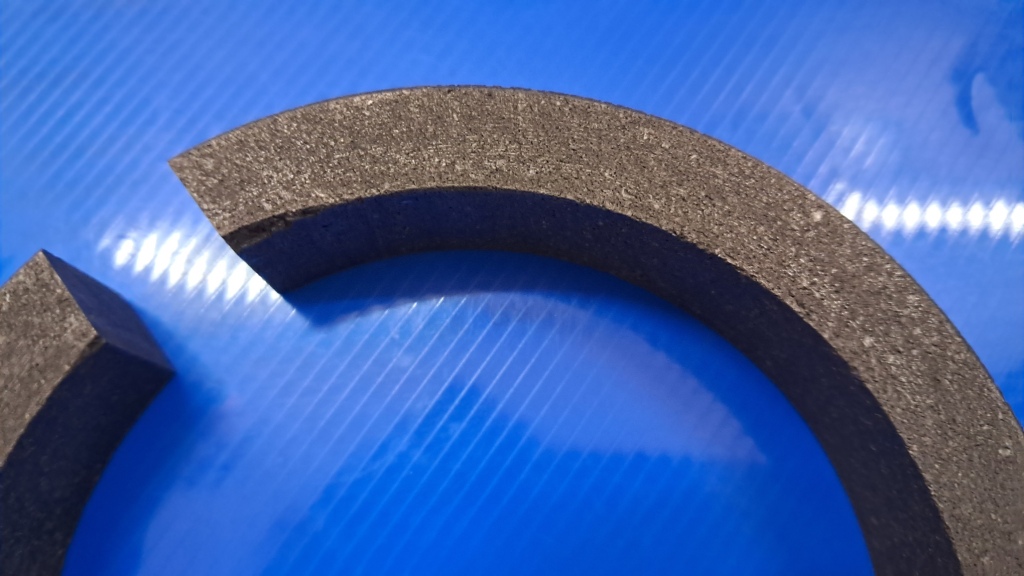

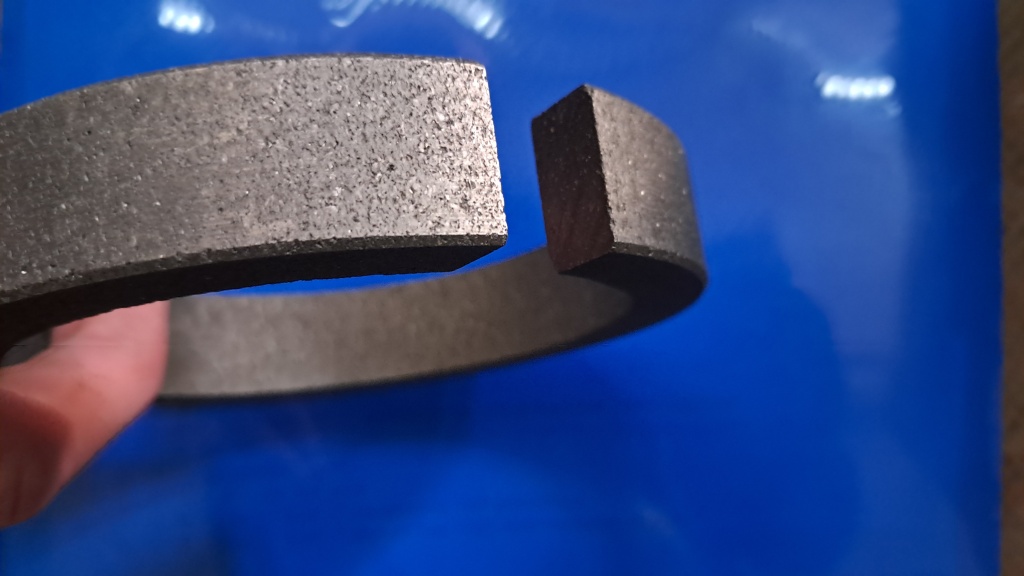

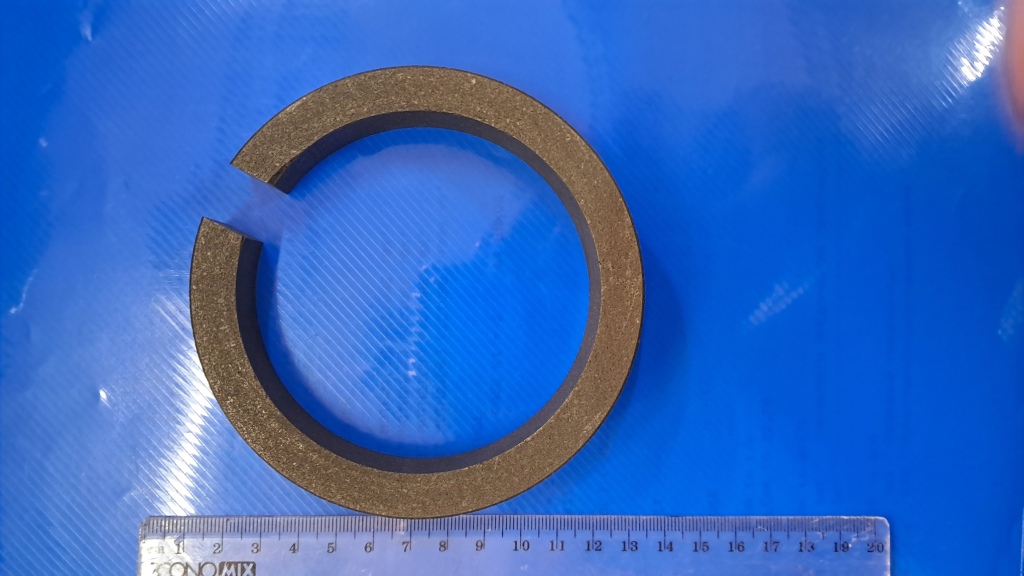

Graphite for nuclear reactors (it has never been used) |

|

|

|

|

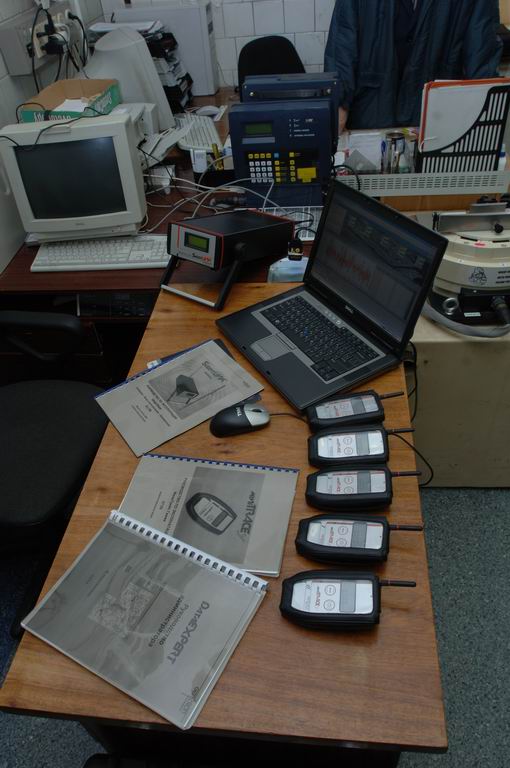

Chornobyl Exclusion Zone |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

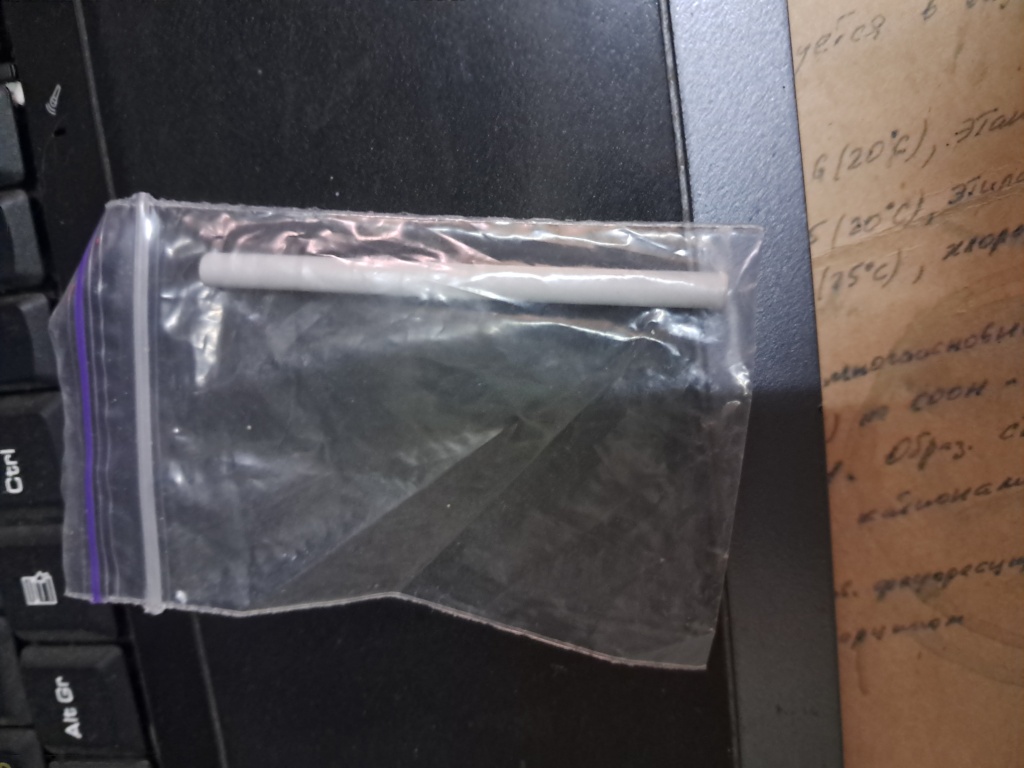

The bonus. The photo below shows a beryllium oxide (BeO) rod. Despite its high toxicity, beryllium and its compounds are widely used in nuclear technology. For example, metallic beryllium is used to make X-ray tube windows. Additionally, beryllium, when combined with alpha-emitting isotopes, serves as a source of neutrons.

|

|

Бонус. На фото ниже показан стержень из оксида бериллия (BeO). Несмотря на высокую токсичность, бериллий и его соединения широко используются в ядерной технике. Например, металлический бериллий используется для изготовления окон рентгеновских трубок. Кроме того, бериллий в сочетании с альфа-излучающими изотопами служит источником нейтронов.

|

A beryllium oxide (BeO) rod |

|

Комментарии

К1

В этом случае, конечно, серная. Но ещё таким образом действует, например, селеновая кислота - и не только.

|