Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2026

Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts

| Content | Chemistry experiments - video | Physics experiments - video | Home Page - Chemistry and Chemists |

|

Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2026 Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts |

Electrospinning - pt.1, 2 Chemist |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

My Introduction to Electrospinning - Part 1

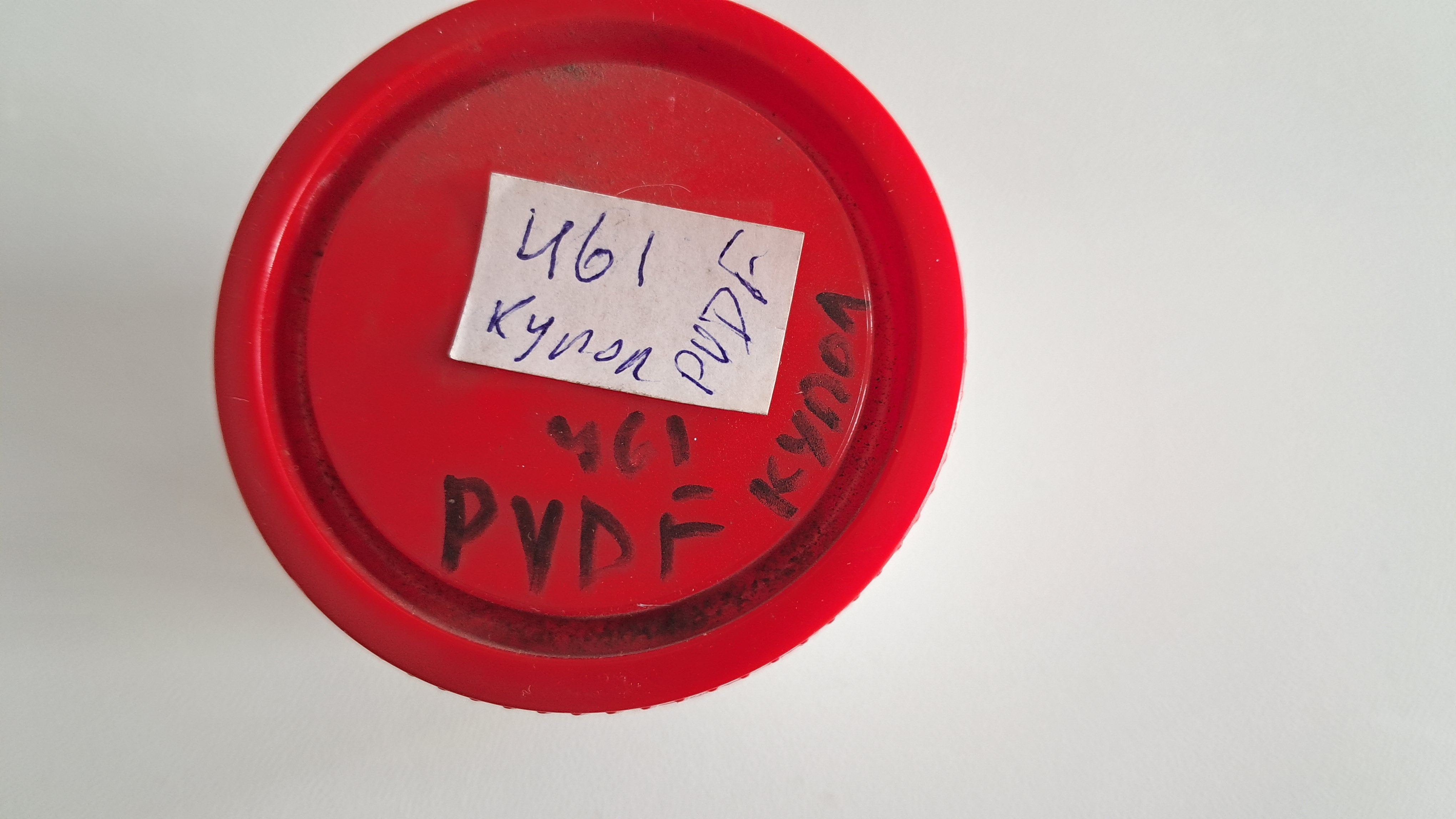

Many years ago, two colleagues told me about their experience with electrospinning. One was a physicist, the other a chemist. They succeeded in producing polyvinylene difluoride (PVDF) fibers from a dimethylformamide (DMF) solution by using an old computer monitor as a transformer.

Электроспиннинг Мое знакомство с электроспиннингом - Часть 1 In English, the word "spinning" conjures up images of the spinning process and of a spindle, but in Ukrainian, these words are pronounced differently. However, in our language, the word "spinning" refers to a type of fishing rod. I used to love fishing, so I remembered my colleagues' story. Unfortunately, they abandoned the work before it reached its logical conclusion. After many years, the idea arose to continue their work. It was interesting, but I was hesitant to pursue it, as it was a different field of science. I am a chemist, and electrospinning is almost pure physics. After some thought, I decided to take up electrospinning because I need scientific publications for my reports. This is a long story, and most importantly, it's far from complete, so I'll try to describe it all in order. First, I'll briefly outline the method.

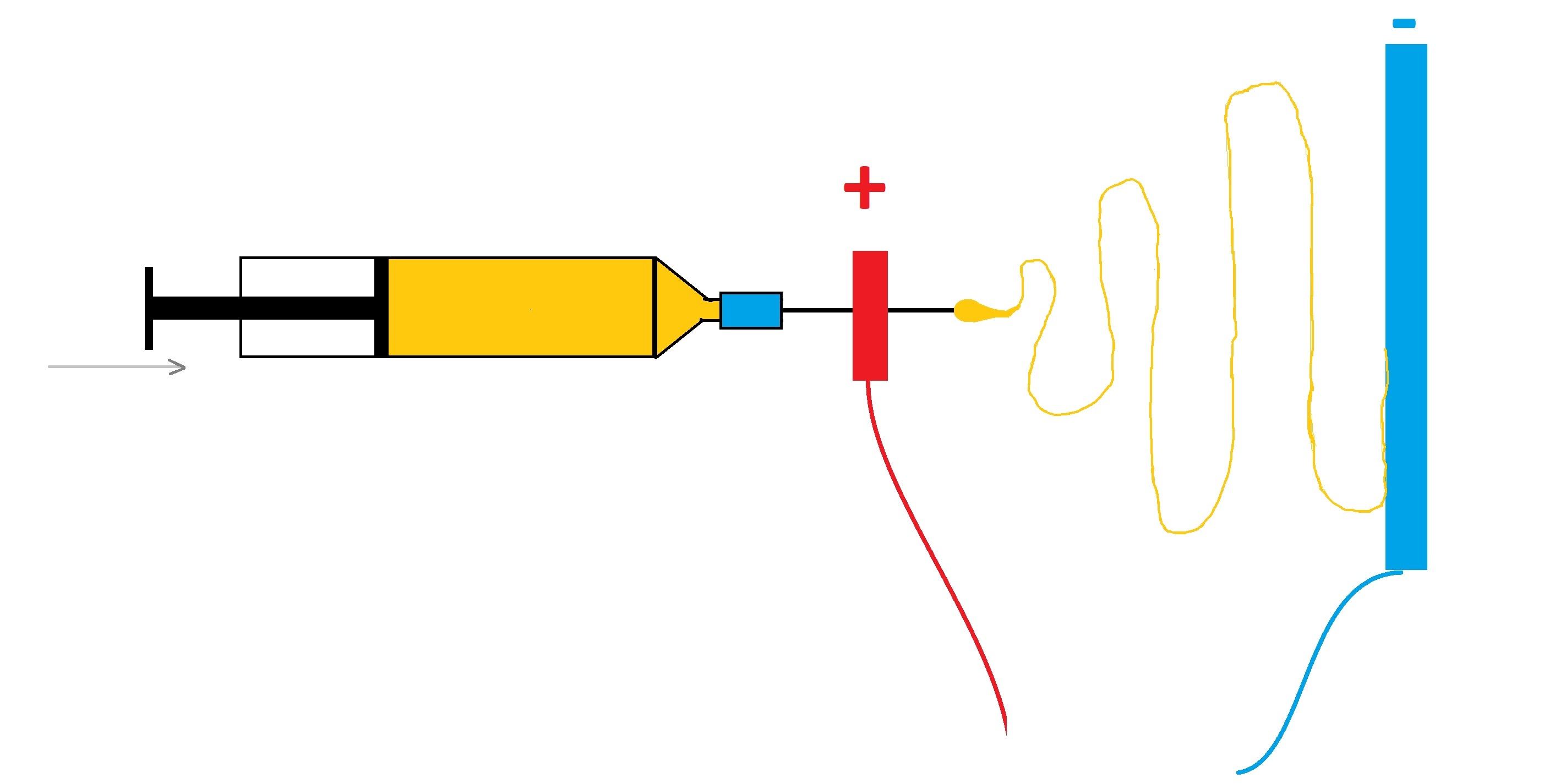

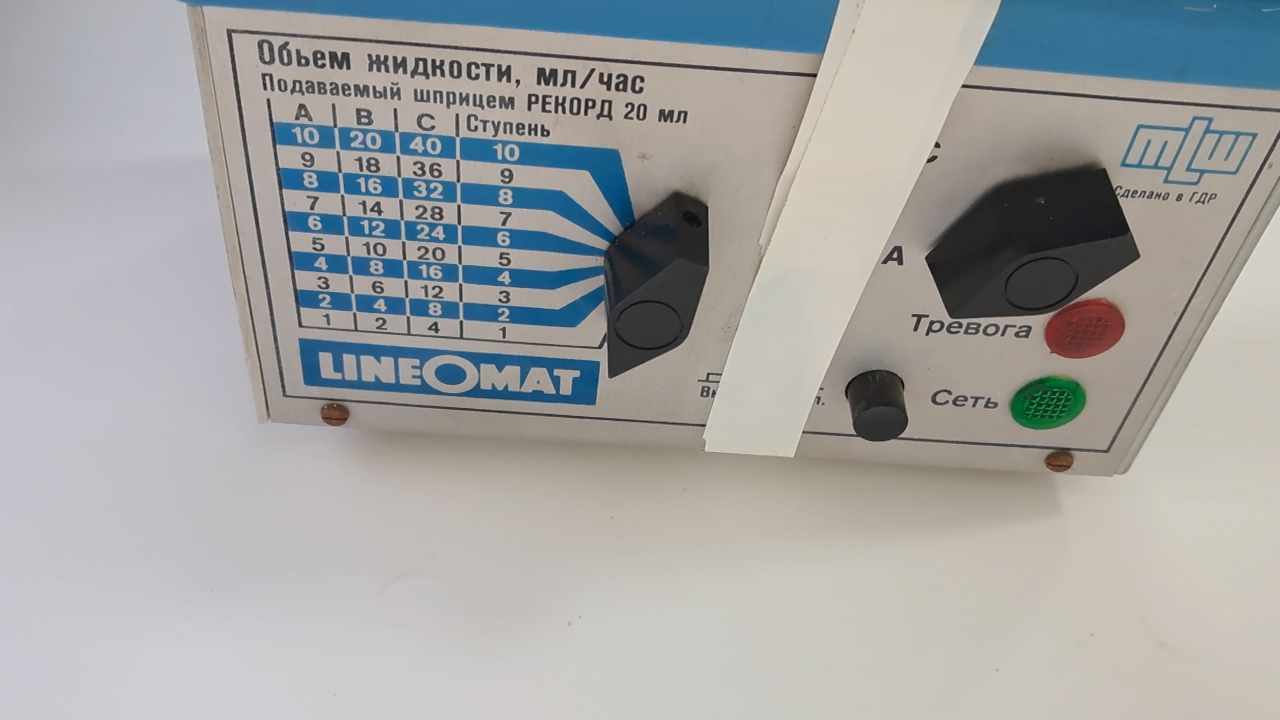

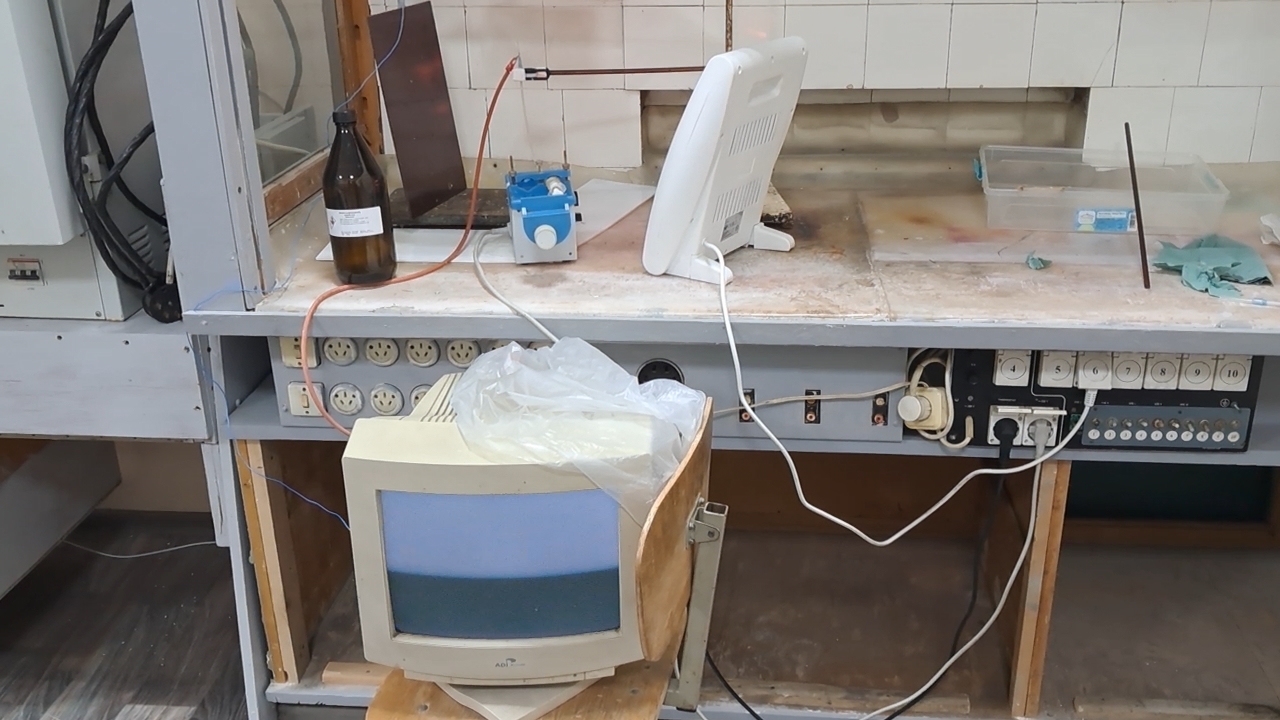

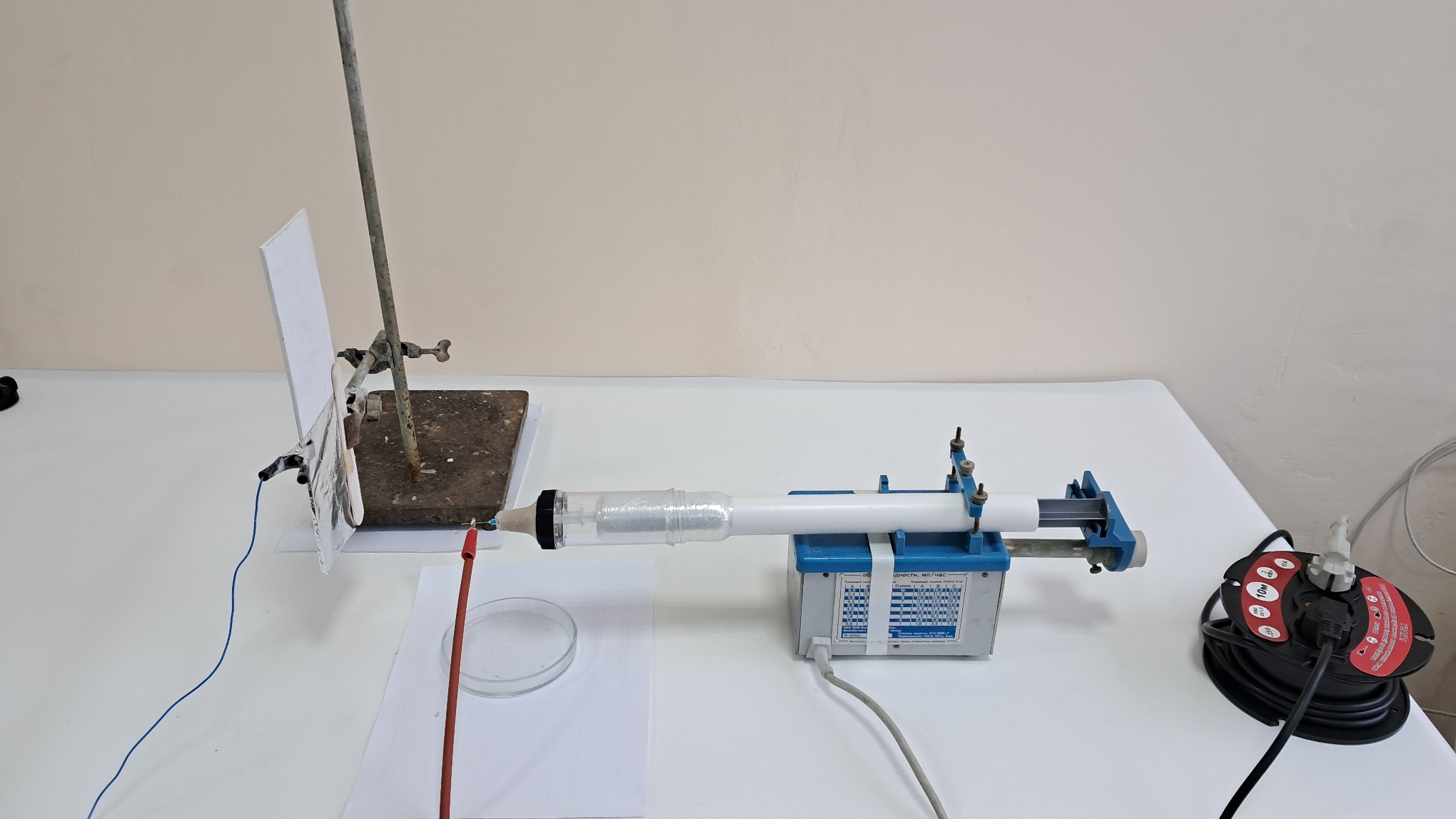

Since a high voltage is applied to the liquid, like charges repel each other, trying to expand the droplet as much as possible. At the same time, the surface tension force acts in the opposite direction, trying to compress the droplet, reducing its surface area as much as possible. The two forces compete. Without the counter electrode, the droplet would simply expand as a result of the applied electric potential. However, a few centimeters (or tens of centimeters) away from the droplet is a negative electrode, usually a metal plate or a rotating drum. The positive charges in the droplet are attracted to the negative electrode, drawing the liquid along with them in a cone-shaped formation known as a Taylor cone. This causes a thin stream of solution to shoot toward the negative electrode. The stream lengthens and thins as it travels due to electrostatic repulsion, performing whip-like movements and gradually dries. This forms a solid polymer fiber, which is attracted to and adheres to the opposite electrode (the collector). Depending on the process conditions, nano- or microfibers are formed. The fibers combine into a fabric-like structure. A non-woven fibrous material forms on the electrode, which has potential for a wide variety of applications, from medicine and pharmacology to filtration, cosmetics, and clothing. For successful electrospinning, the polymer solution must have sufficient viscosity; otherwise, the stream may disintegrate into individual droplets. Electrospinning is replaced by electrospraying (formation of an aerosol under the influence of an electric field). However, the viscosity of the polymer solution must not be too high, otherwise the electrostatic force will not be able to draw a jet out from the droplet. Electrospinning doesn't require the use of a syringe needle or any needle at all: there are other variations. For example, a metal roller in a bath of polymer solution can serve instead of a needle. Two needles can be positioned coaxially, each delivering a different polymer solution simultaneously. A polymer suspension or melt can be used instead of a solution. However, these variations don't change the essence of the method. What did we have on hand? An old computer monitor with a cathode ray tube and two electrodes connected to its transformer. We also had several laboratory stands, a syringe pump, aluminum foil, plastic sheets, two bottles of DMF (solvent), and a small jar of PVDF. Of course, laboratory electrospinning setups are readily available, and you can even buy an industrial setup, but our institute hasn't purchased new equipment for many years. Therefore, everything will have to be made by ourselves, using items and materials that we have on hand or can buy ourselves. One of my colleagues was completely demotivated to work as a scientist. The other retained his desire to pursue science, but was overwhelmed with paperwork and then fell ill, putting him out of action for a long time. As a result, I conducted trial experiments with the first colleague only, after which I had to work on my own. The first colleague obtained some necessary things for the experiment, while the second colleague gave me advice over the phone. I hope the second colleague will get well soon, and the first will change his mind and rejoin the work. |

Electrospinning |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

Electrospinning: Solution of PVDF in DMF (Unsuccessful Experiment) - Part 2

I asked the colleague to assemble the setup so that we could begin producing PVDF (polyvinylidene difluoride) fibers. He agreed, telling me how badly he needed PVDF nanofibers for his work with tritium. However, each time, he came up with a new excuse to postpone the experiment for a few days. Several weeks of delays passed with no end in sight. I finally lost patience and called a second colleague, explaining the situation:

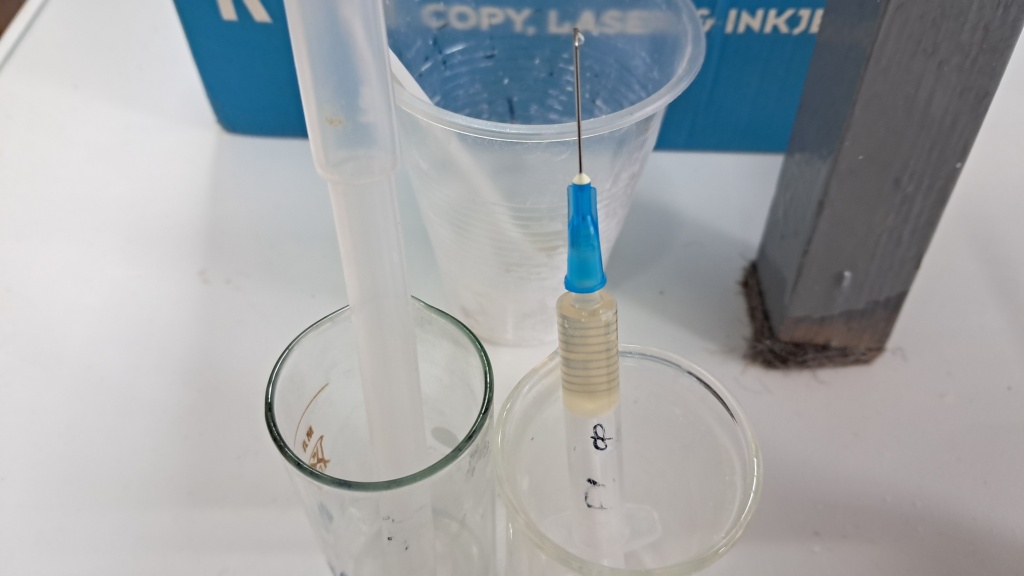

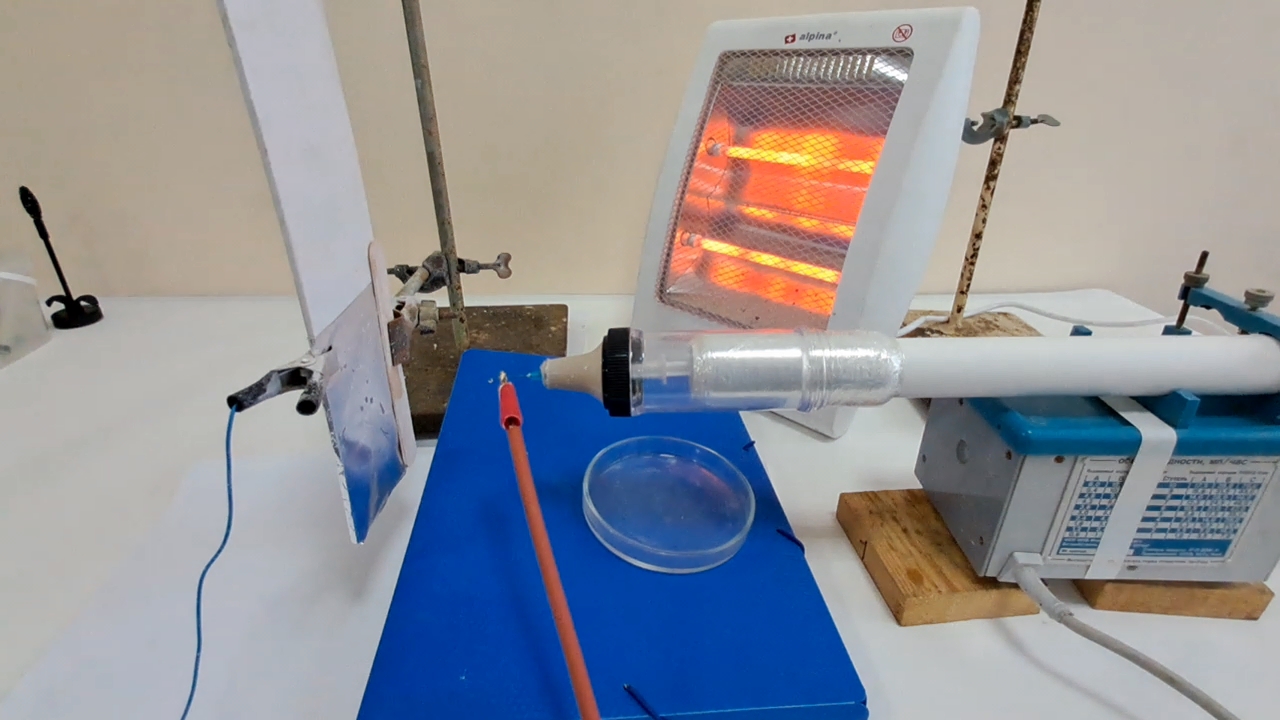

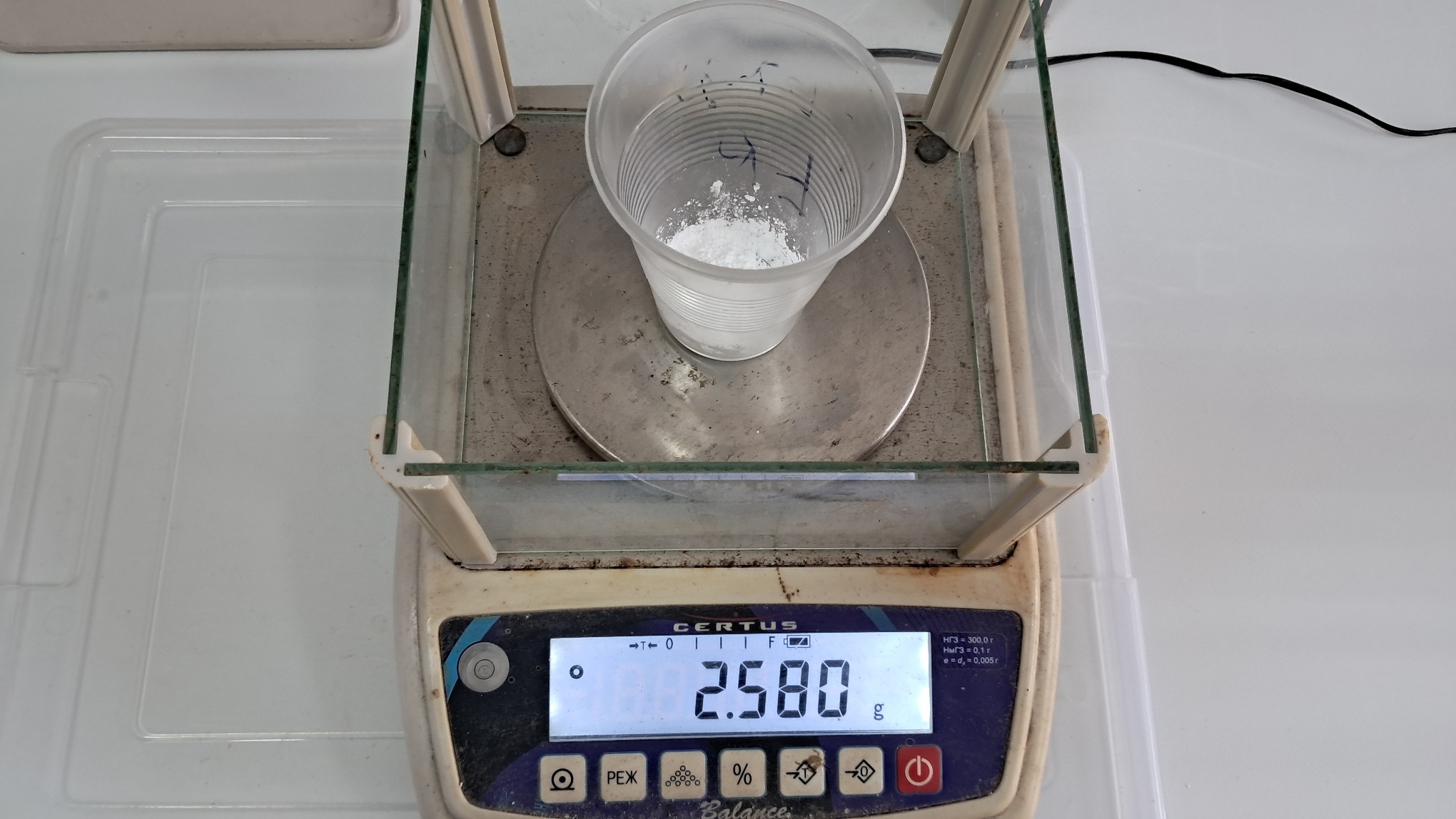

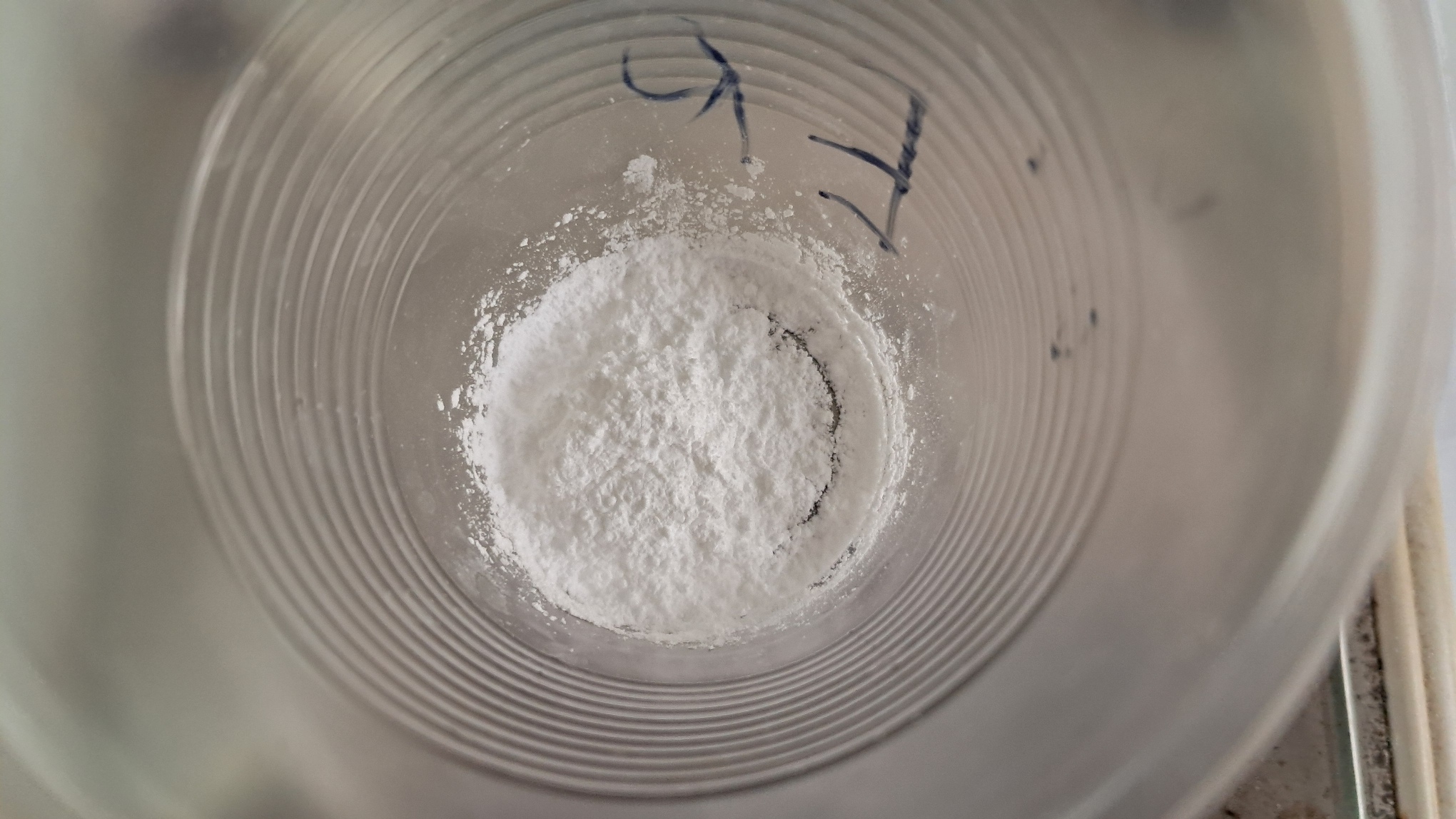

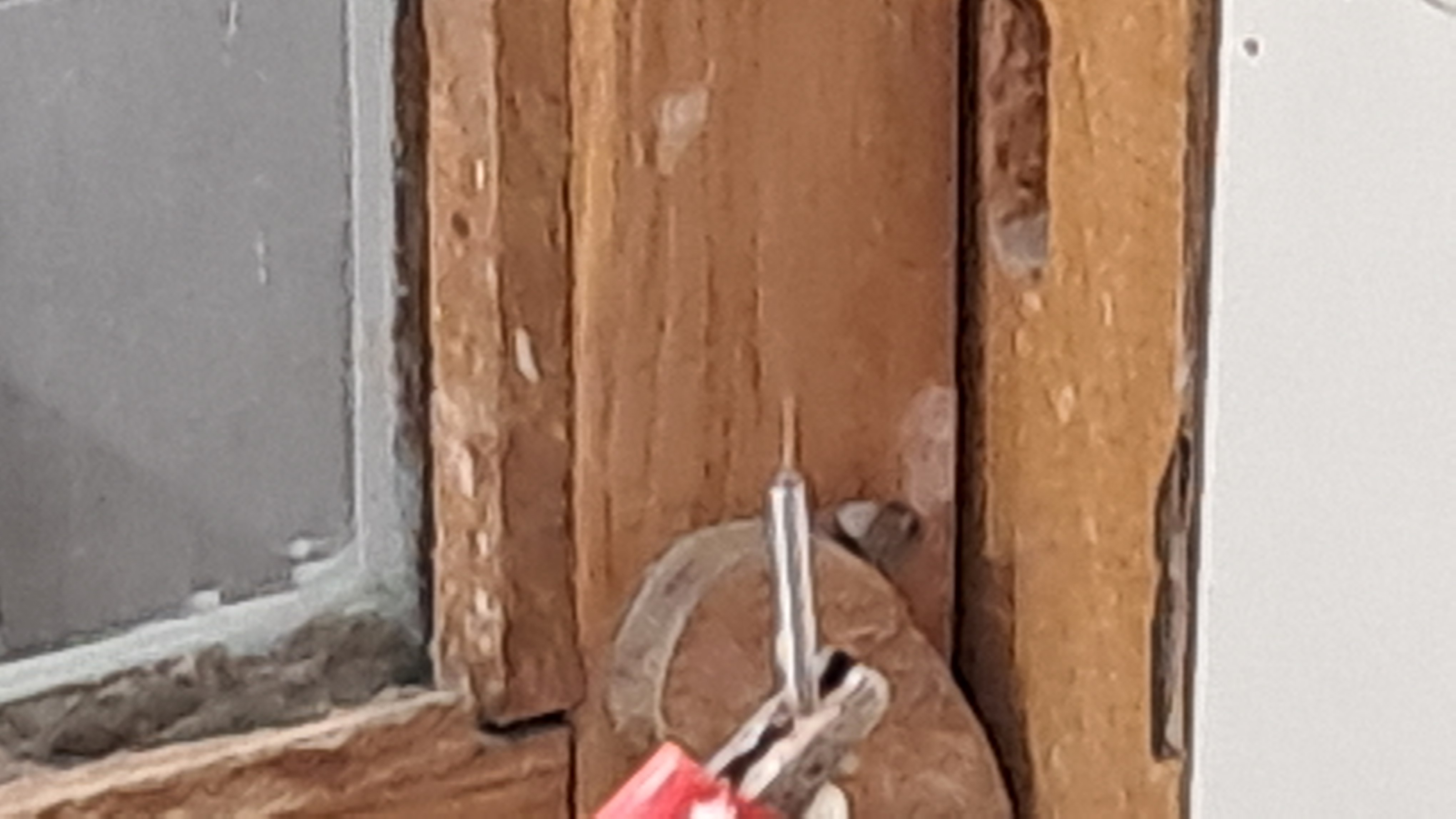

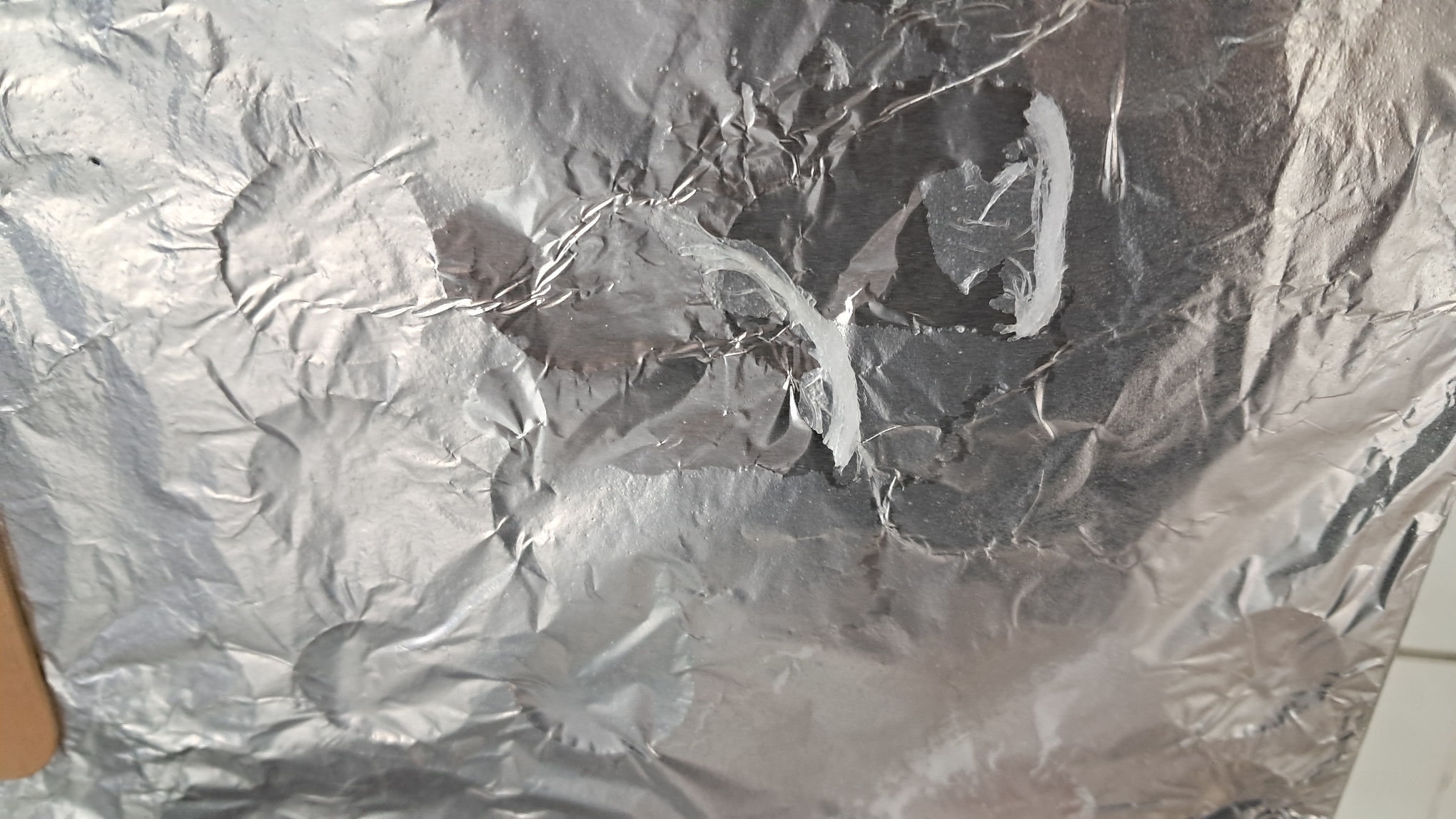

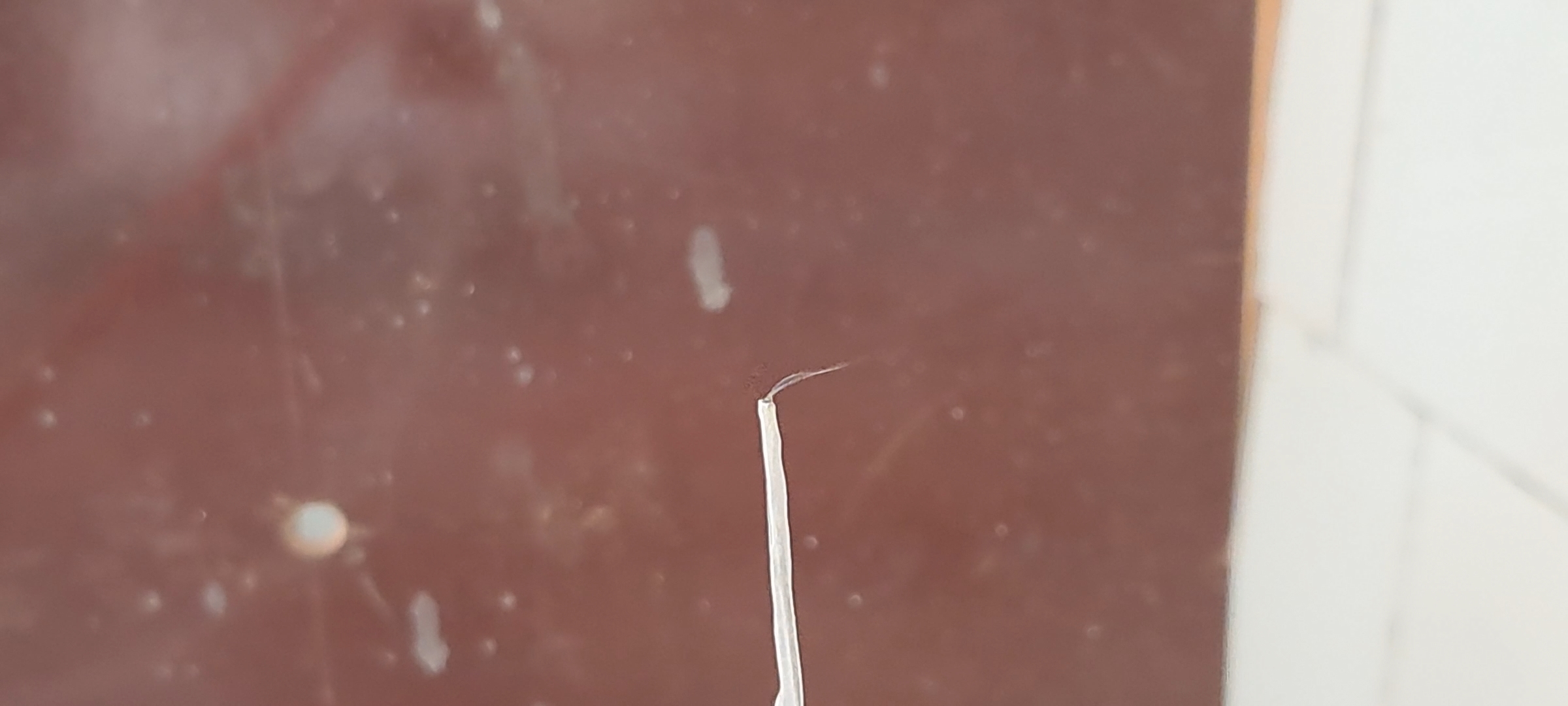

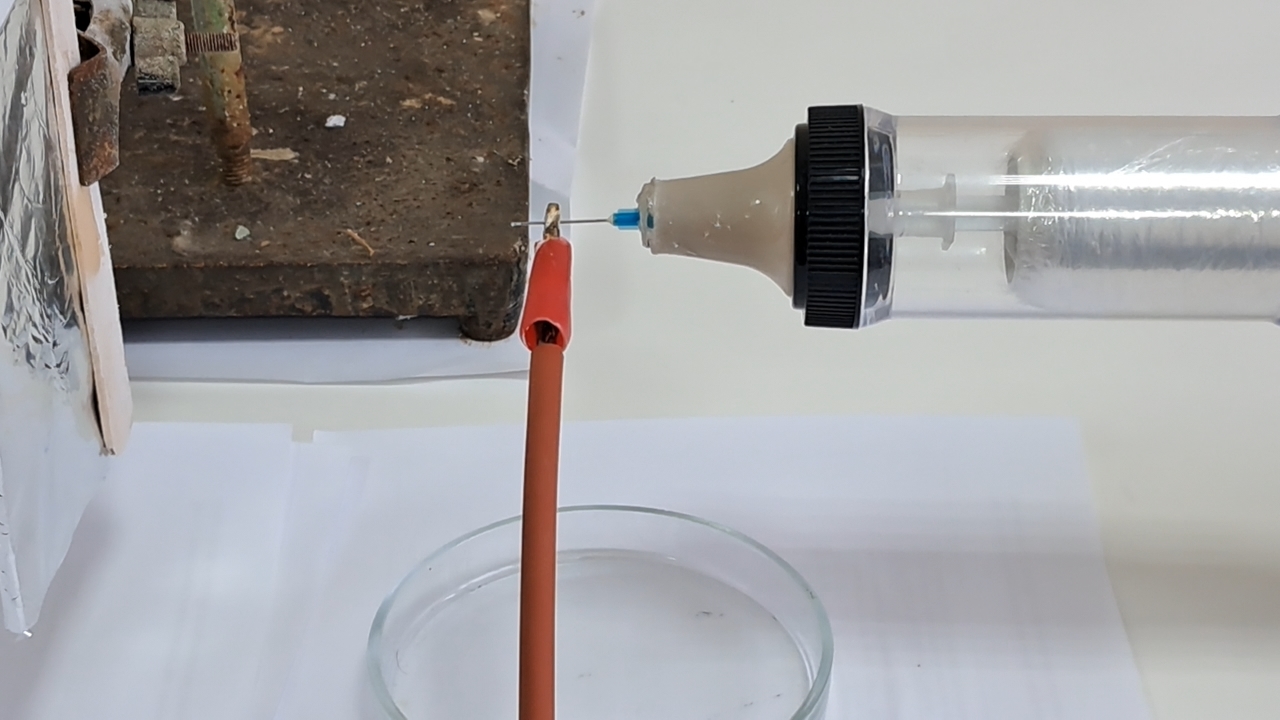

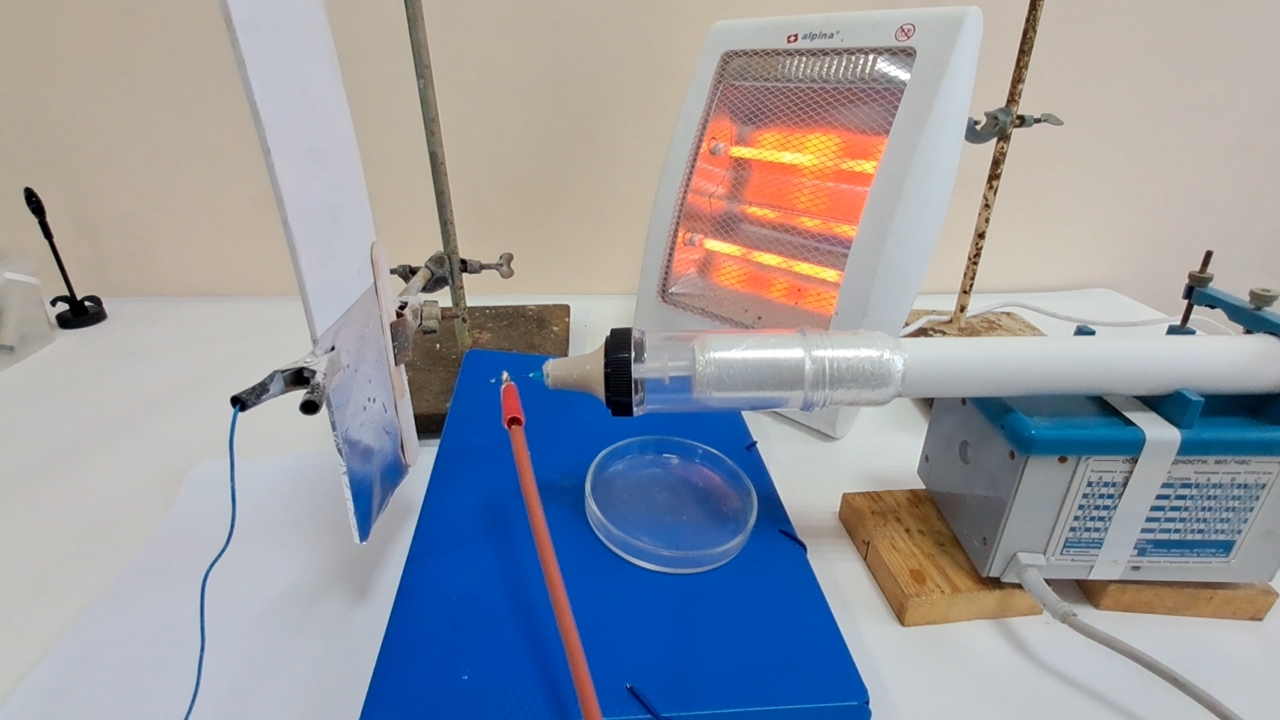

Электроспиннинг: раствор PVDF в DMF (неудачный эксперимент) - Часть 2 "Unfortunately, I've never done electrospinning, so I don't know how to start the experiment, and our colleague keeps giving me empty promises to help. He always finds a new excuse to do nothing. He's a master at inventing reasons to postpone work. I'm not his boss, and you, unfortunately, are temporarily out of action. Even if I could force him to work, I wouldn't - there should be no such thing as serfdom in science. As a result, there's no one to start the experiment. If neither of you is interested in electrospinning anymore, I won't be able to do this job alone. I'll have to start a project that I actually understand, like synthesizing isopropyl nitrate or some surfactant." I don't know what the second colleague said to the first, but the very next day we began the experiment. My colleague asked me to prepare a 10% PVDF solution. He said, somewhat hesitantly, that they had used that concentration before. We drew the solution into a 10 mL syringe and mounted it on a syringe pump. The syringe plunger was homemade, made of polytetrafluoroethylene. A plastic tube about 20 cm long was attached to the syringe nozzle, and a syringe needle was connected to the end of the tube. It would have been more logical to attach the needle directly to the syringe, but the design of the syringe pump did not allow this - the high-voltage electrode would have been too close to the pump body. This intermediate tube later caused me problems. The needle and tube were secured using a plastic clip and an ebonite rod. A standard clamp on a retort stand was unsuitable, since it is metallic and conducts electricity well. The needle was oriented vertically, with the tip facing upward. The negative electrode - a square piece of plastic wrapped in aluminum foil - was placed above the needle. I asked my colleague: "What should the distance be?" "We set the distance between the electrodes to 15-20 cm." Unlike my colleague, I had never performed such an experiment, so I did not know what an electrospinning setup should look like during normal operation. What should the fibers detaching from the needle and traveling toward the collector look like? My colleague said that the fiber diameters ranged from hundreds of nanometers to tens of microns - dimensions that would be difficult to detect with the naked eye. I had never even seen photographs or videos of electrospinning. This lack of experience had an unfortunate consequence: I could not visually determine whether the experiment was proceeding successfully. Perhaps the process was running normally and required no intervention, or perhaps no fibers were forming at all and adjustments were needed. I could only rely on my colleague's judgment - and he, like me, was not a physicist. The setup was assembled, the syringe pump was started, and then the computer monitor was turned on. Hissing and whistling sounds could be heard. Externally, nothing seemed to change. My colleague said that the fibers escaping from the needle formed a "fog cone." Individual fibers, of course, are invisible, much like the tiny droplets of water that form fog. However, a stream consisting of many fibers should be quite visible. The problem was that we could not see any cone. Ignoring my colleague's protests ("Careful!" "There's high voltage there!"), I moved my phone close to the high-voltage needle and started recording. I was able to discern a stream emanating from the needle and breaking off a few centimeters above the tip. The liquid filament most likely disintegrated into individual droplets, which were then attracted to the negative electrode. Instead of electrospinning, we were observing electrospraying - the formation of an aerosol under the influence of an electric field. Incidentally, this is how cars used to be painted. And what was on the collector plate? A wet, translucent film had formed. By the next day it had dried, turning into a white coating that adhered only weakly to the aluminum. I placed a piece of this material under an optical microscope - no fibers were visible. I photographed the coating by holding my smartphone camera up to the microscope eyepiece and sent the images to my second colleague, a physicist. He agreed that there were no fibers. My last doubts vanished - the first experiment had failed. What was the reason for this negative result? To answer that question, I began studying scientific articles on electrospinning and then watched several YouTube videos. Some of these videos were particularly helpful, as their authors clearly demonstrated the technique and discussed practical features that are not usually described in scientific papers. In particular, I finally saw what the fibers forming at the tip of the needle and moving toward the collector should actually look like. There were many possible reasons for the failure, but I identified two that seemed the most likely. First, the solution might have been insufficiently viscous because the polymer concentration was too low; as a result, the liquid jet broke up into droplets. The second likely cause was that the monitor's transformer did not provide a sufficiently high voltage. Preparing solutions with different PVDF concentrations was easy (I am a chemist, after all). My knowledge of transformers, however, was limited to their general operating principles. I asked my first colleague: "Did you produce PVDF fibers using this monitor?" "No, it was a different monitor. Unfortunately, they threw it out." "Have you tried using this particular monitor for electrospinning?" "We haven't, but it doesn't matter - monitors produce roughly the same voltage." I seriously doubted that all old computer monitors operated at the same cathode-ray tube voltage. I asked how many kilovolts this monitor's transformer produced, and whether that voltage could be measured. "About 10-20 kilovolts. We haven't measured it. How can I measure it? Ask our second colleague." Much later, I did ask him. It turned out that measuring such a voltage would require a voltage divider, which we did not have. Buying such a device for a single measurement seemed irrational. However, the second colleague assured me that "not all He also mentioned that approximately 10 kilovolts can cause electrical breakdown over 1 cm of dry air (later I learned that the more accurate value is 30 kilovolts). In theory, this provides a way to estimate the voltage, but in practice a spark discharge can destroy the monitor. By that time, I had already involuntarily "tested the size of this gap" three times, so I replied that our monitor produced breakdowns at distances of about 3-4 cm, although the air in the laboratory was certainly not "absolutely dry." Since I could neither change the transformer voltage nor reliably measure it, I decided to focus on the PVDF concentration. After my colleague had shown me the basic technique, I could continue the experiments on my own. Looking ahead, I will note that I abandoned the "tip-up" needle orientation for a long time and returned to it only after a couple of months - just today, as I am writing these lines. |

Electrospinning: Solution of PVDF in DMF (Unsuccessful Experiment) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|