Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2026

Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts

| Content | Chemistry experiments - video | Physics experiments - video | Home Page - Chemistry and Chemists |

|

Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2026 Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts |

Electrospinning - pt.3, 4 Chemist |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

Electrospinning: Solution of PVDF in DMF (Continued) - Part 3

The next day, I began the experiment on my own. I prepared a 20% PVDF solution in DMF and then a 25% solution. The latter proved to be too viscous. I struggled to draw it into the syringe, attached the tube, and tried to expel the air in order to fill the tube with solution. Because of the excessive pressure, the tube flew out of the syringe, spraying my trousers and sneakers with a glue-like polymer solution.

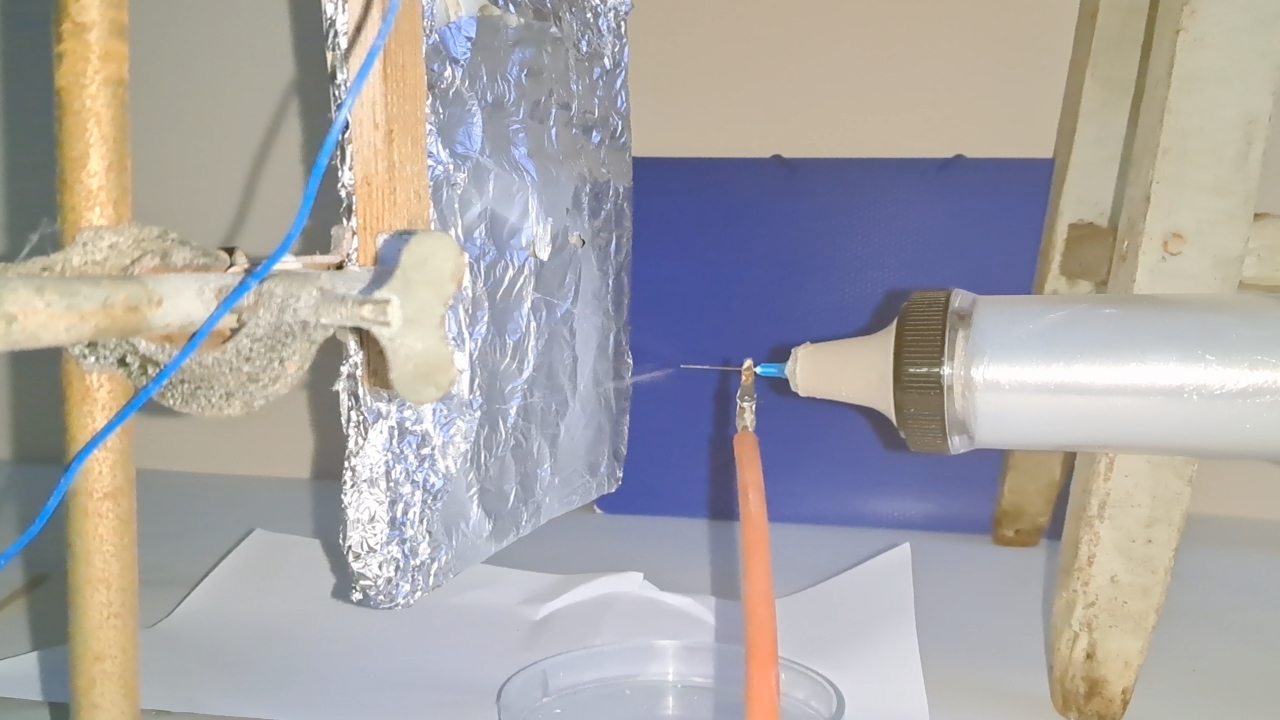

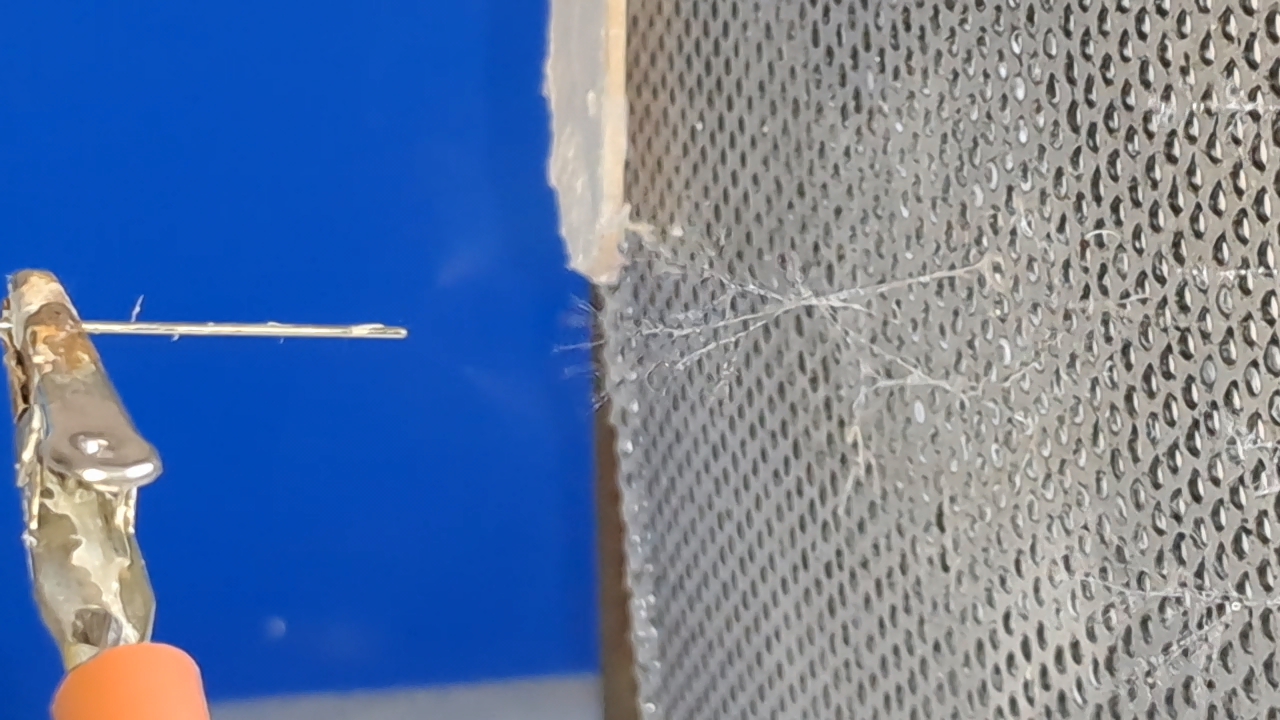

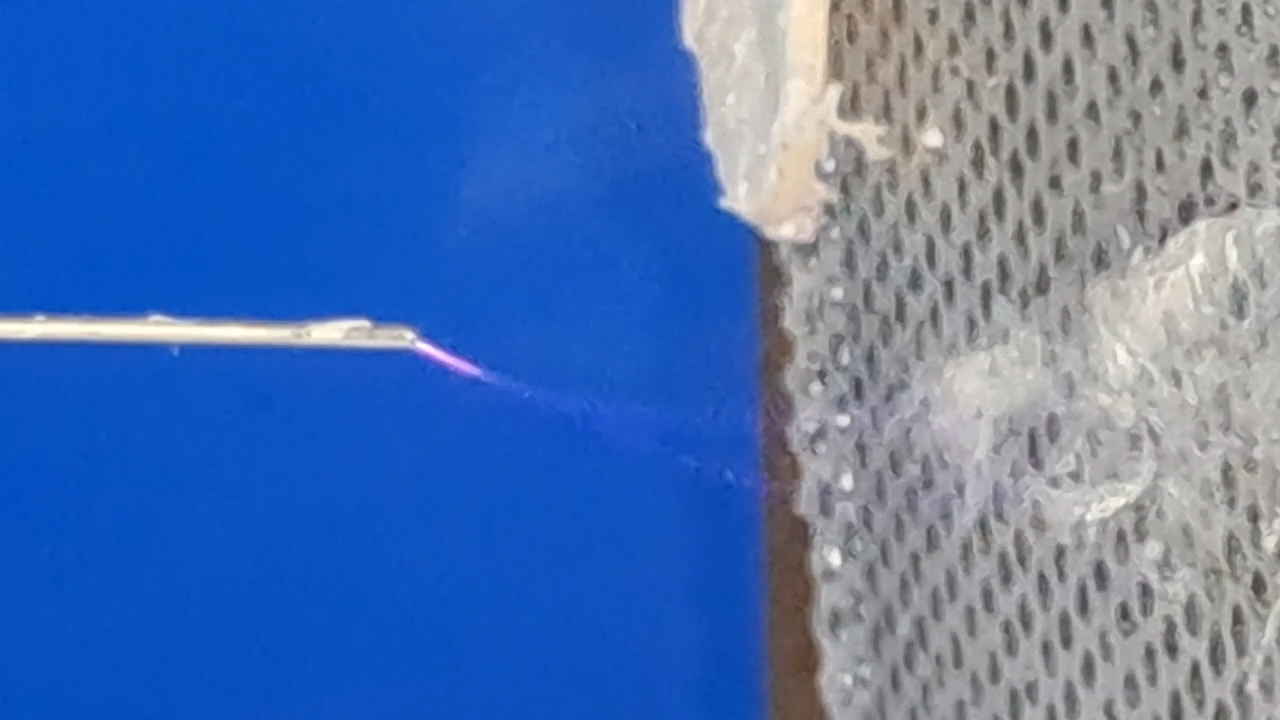

Электроспиннинг: раствор PVDF в DMF (продолжение) - Часть 3 It also turned out that the plastic hub of the needle had partially dissolved in DMF during the previous experiment. Strictly speaking, it was not a syringe needle but a cannula needle. I had to replace it with a standard syringe needle, which I secured to the end of the tube with tape. I then filled the syringe with the less viscous 20% solution and again squeezed the air out of the tube. Soon afterward, the needle clogged. Apparently, polymer solution had remained in the tube after the previous experiment, dried, and formed viscous clumps. Last time we had rinsed the tube after finishing the work, but clearly it had not been cleaned thoroughly enough. I disassembled everything and carefully cleaned, washed, and rinsed both the needle and the tube. I reassembled the setup as before, started the process, and obtained the same result: no fibers formed. When my colleague came over, it turned out that I had unknowingly set the solution flow rate to the maximum. Such a high flow rate could indeed have caused the failure. However, reducing the flow rate to the lowest possible value did not help either. At this point, I decided that since electrospinning itself was not working, the setup needed to be redesigned. This would not solve the fundamental problem, but it would make the work more convenient. Unlike my two colleagues, I planned to experiment not only with polyvinylidene difluoride but also with other polymers. The most important change was to secure the needle directly on the syringe nozzle, without using an intermediate tube. The tube could easily come loose or become clogged with hardened polymer. To keep the syringe pump away from the high-voltage needle, the syringe itself therefore had to be positioned outside the pump. I initially planned to use a wooden plank for this purpose, but the colleague brought a length of plastic water pipe instead. The pipe, though not without difficulty, fit into the pump holder. Inside it, we placed a plunger from a larger syringe and a plastic rod, which transmitted the mechanical force from the pump to the plunger of the syringe containing the polymer solution. This raised a new question: how could the syringe be fixed at the opposite end of the pipe? It had to be held securely and positioned precisely, yet still be easy to remove after use. My colleague soon lost interest in the work and left, but he did leave behind a plastic pastry syringe with a set of tips. Such syringes are normally used for applying cream to cakes. The tips were attached to the syringe by a union nut. The diameter of the pastry syringe was slightly larger than that of our pipe. In principle, the pastry syringe could be fixed to the end of the pipe, and then the syringe containing the polymer solution could be placed inside it, with the needle passed through the pastry nozzle opening. I wrapped the end of the pipe in paper and tried to attach the pastry syringe to it, but this did not work. I went to my colleague and asked for some polyvinyl acetate glue to secure the connection. "You won't succeed! That kind of glue won't bond plastic, and besides, it's conductive!" I seriously doubted that dried polymer glue would be electrically conductive, but I did not argue. Instead, I asked my colleague to do it his way. He simply wrapped the pipe in plastic film and attached the pastry syringe to it. This temporarily solved the problem: the syringe stayed in place. Much later, during experiments, this connection lost its strength twice at the most inopportune moments. The pump continued to operate, but the solution did not flow, because the intermediate rod slowly pushed the pastry syringe outward instead of pressing on the plunger of the inner syringe filled with solution. I eventually solved this problem with tape. It was neither elegant nor impressive, but it worked. During these experiments, another drawback of our primitive setup became apparent. While operating, the syringe containing the solution was hidden inside an opaque tube, making it impossible to determine how much solution remained. To fix this, I used a new pastry syringe tip and cut it so that the syringe with the solution protruded completely, except for the plunger and the barrel flange. I also changed the needle orientation from vertical to horizontal, and with it the orientation of the entire setup. I temporarily moved the apparatus from the fume hood to the laboratory bench. I did not want to inhale solvent vapors, especially since the dimethylformamide contained dimethylamine and had a distinctly fishy odor. Nevertheless, working at the bench was far more convenient, particularly because it was easier to observe the behavior of the solution as it exited the needle. Since I was unable to produce fibers from a 20% PVDF solution and the 25% solution was too viscous, I decided to reduce the distance between the electrodes. I asked my first colleague, a chemist, what the minimum safe distance between the electrodes might be. He replied that electrical breakdown would occur at a distance of about 7 cm. I continued the experiments. When I reduced the distance between the electrodes to 10 cm, the smell of ozone became noticeable. Still, no fibers formed. To better observe the flow from the needle, I turned off the laboratory lights, placed a dark background behind the setup, and used my smartphone flashlight for illumination. I then reduced the distance further, to 4-5 cm. The result remained negative - electrospinning did not occur. On one occasion, I observed a purple, seemingly "fibrous" glow emanating from the needle, which I assumed to be a corona discharge. A few seconds later, there was a loud crack, and a miniature lightning bolt flashed between the needle and the plate. Fortunately, the monitor continued to function. Another spark discharge occurred at the very end of the experiment, after I had already turned off the solution supply but before I had switched off the monitor. Incidentally, while the setup was operating, the monitor screen glowed faintly because the cathode-ray tube had not been disconnected from the transformer. This turned out to be important: there was a real danger of touching the high-voltage electrode while the monitor was still on. The LED indicating that the monitor was powered was almost imperceptible, whereas the faint screen glow clearly showed that high voltage was present. Without it, it would have been difficult to tell whether the monitor was on or off. I later called the second colleague, a physicist, and asked him: "I'm going to ask a stupid question. What happens if I accidentally touch the electrode while the monitor is still on? I work alone in the room - there's no one to provide medical assistance. The neighbors won't notice my absence for weeks, until they need me to sign some document. Several times I've turned on the power without attaching the electrode to the needle. Once, the syringe, needle, and electrode - still energized - flew off and landed at my feet." He replied: "I don't know for sure. A relative of mine once tried to repair a large cathode-ray-tube television. He was thrown across the room, but otherwise not injured. Our monitor operates at a lower voltage, but you really shouldn't take the risk. Always turn it off by pulling the plug, not by pressing the button. It's worse for the monitor, but better for you." I promised to follow his advice, but I did not keep my word - the wall outlet was flimsy and would not survive many on-off cycles. The colleague also suggested that I visit his laboratory to pick up a homemade syringe pump they had used previously, as well as two containers of a PVDF/DMF solution. They had not worked with this solution before, but since it was already prepared, there was no reason not to try it. |

|

|

|

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

Electrospinning: Solution of PVDF in DMF (Ending) - Part 4

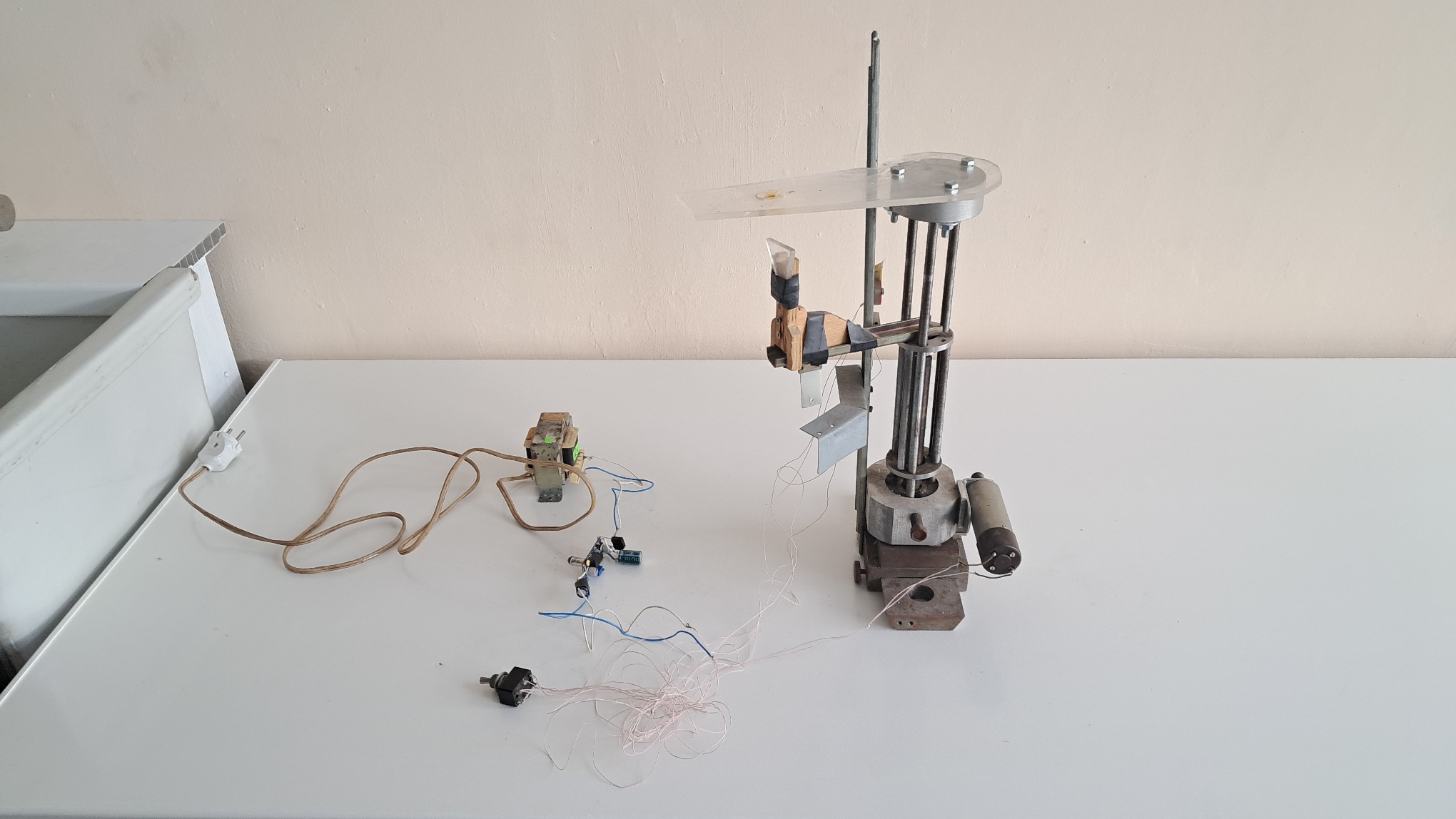

The first thing my chemist colleague and I did was test a homemade "syringe pump" that I had borrowed from my physicist colleague. I did not like the appearance of the device, especially the tangled, thin wires. However, a pump is supposed to pump liquid, not merely look neat. We switched it on and immediately noticed that the motor and gearbox were rotating jerkily. The syringe pump was clearly faulty.

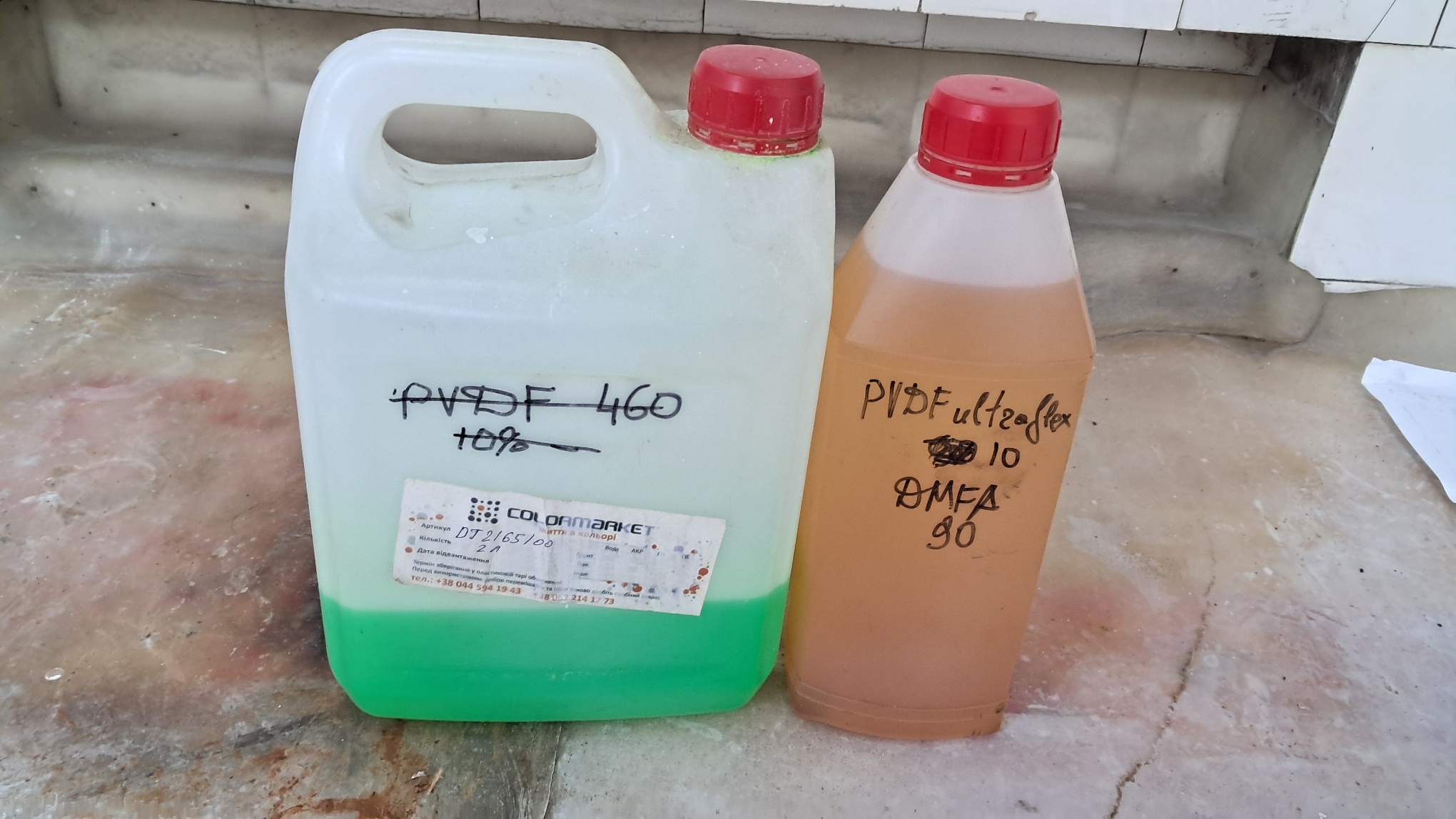

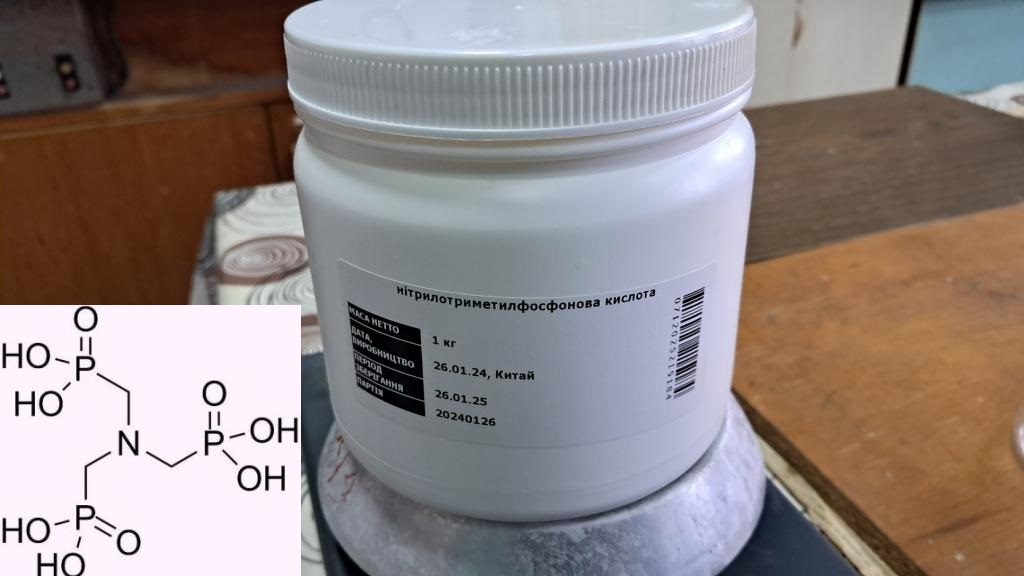

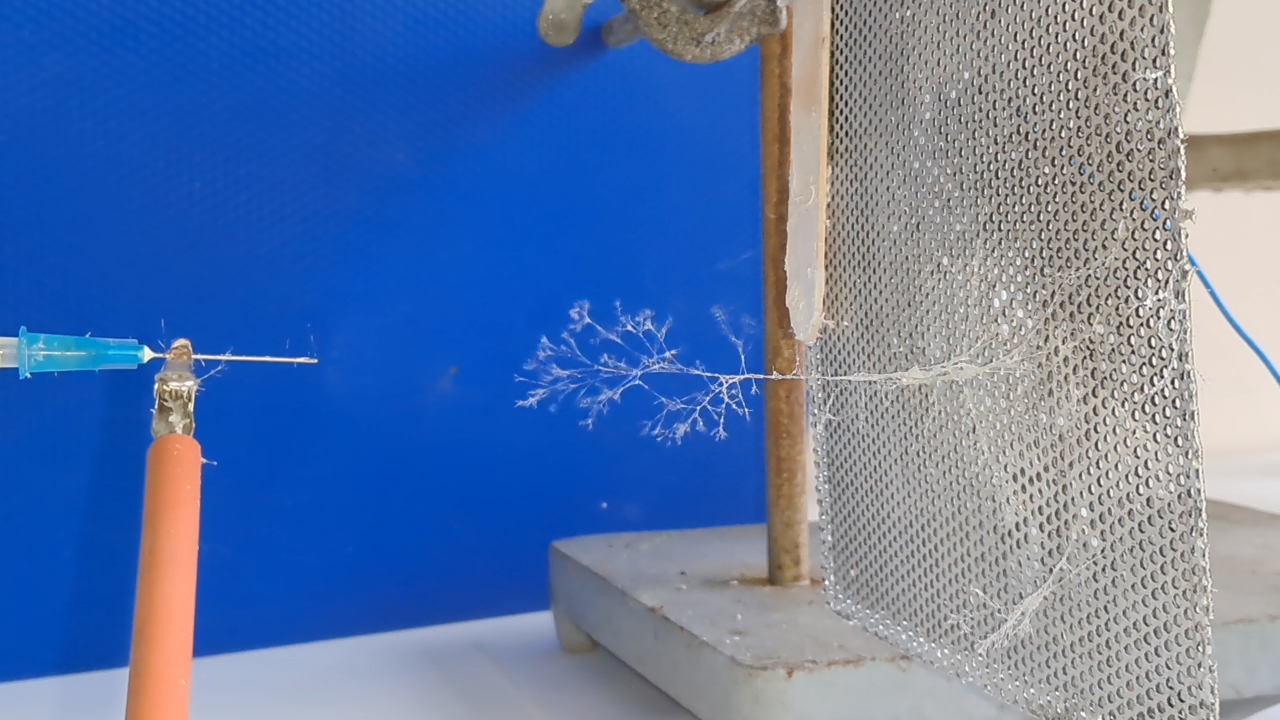

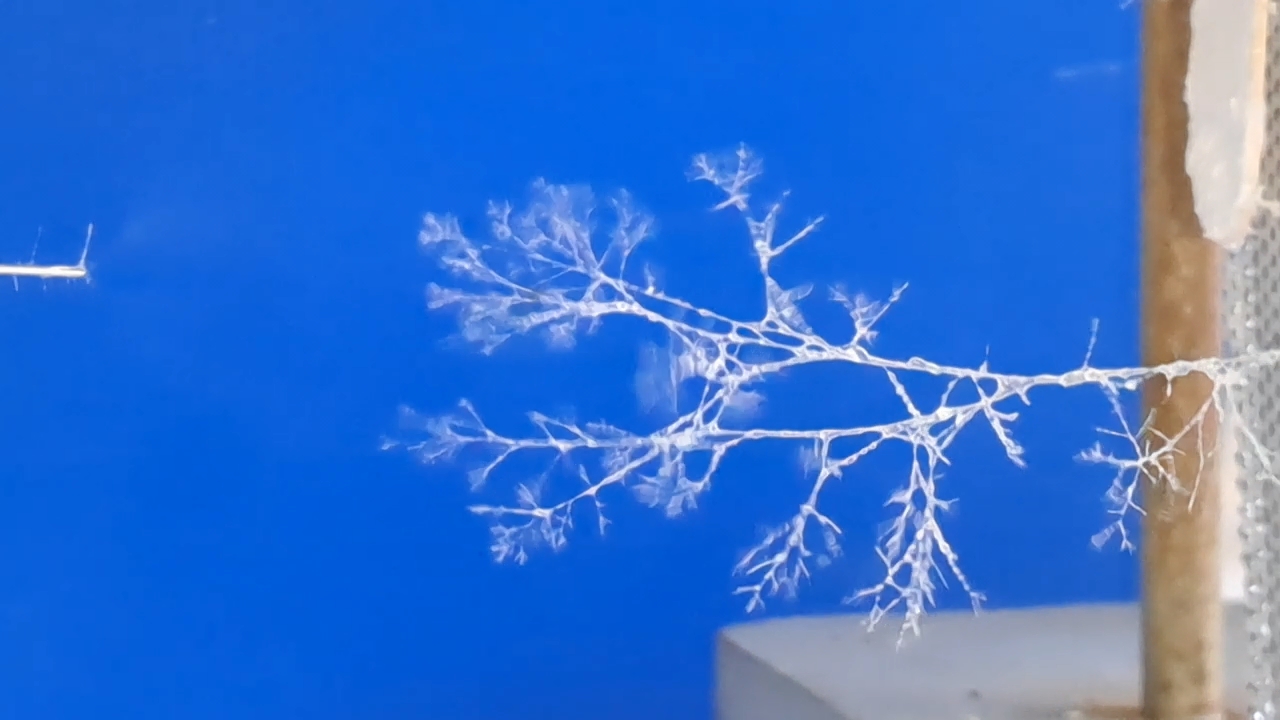

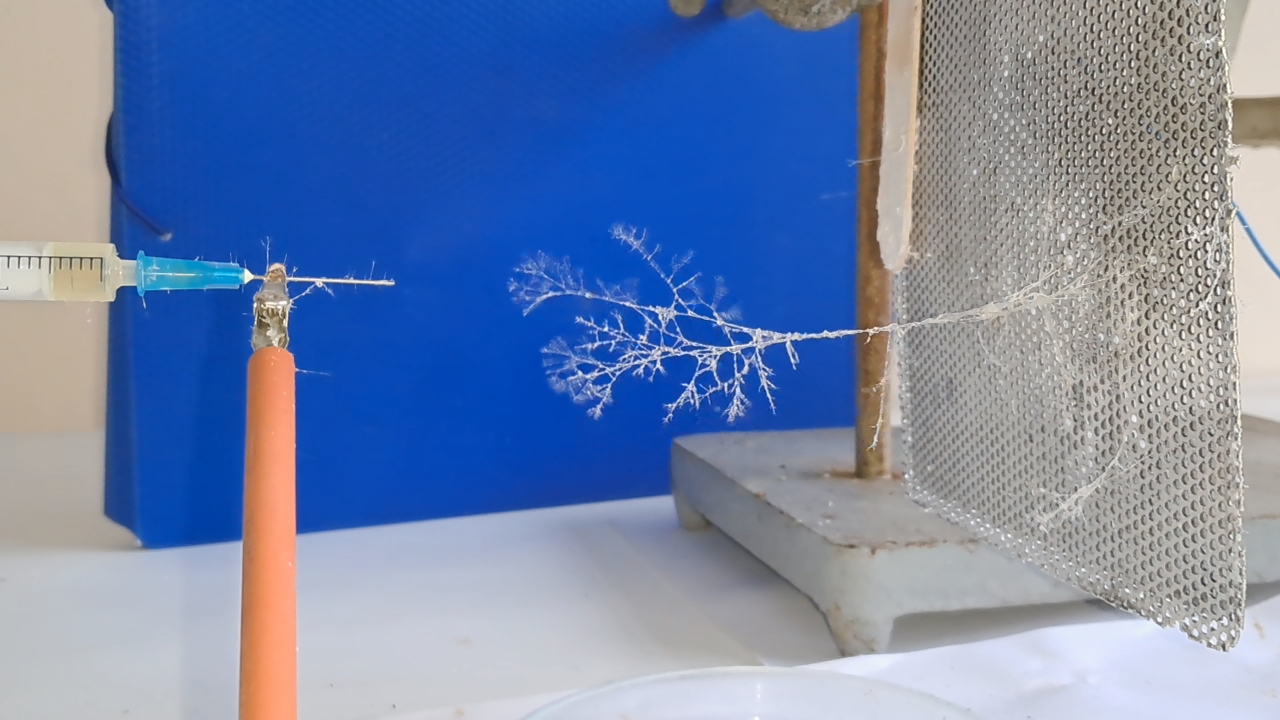

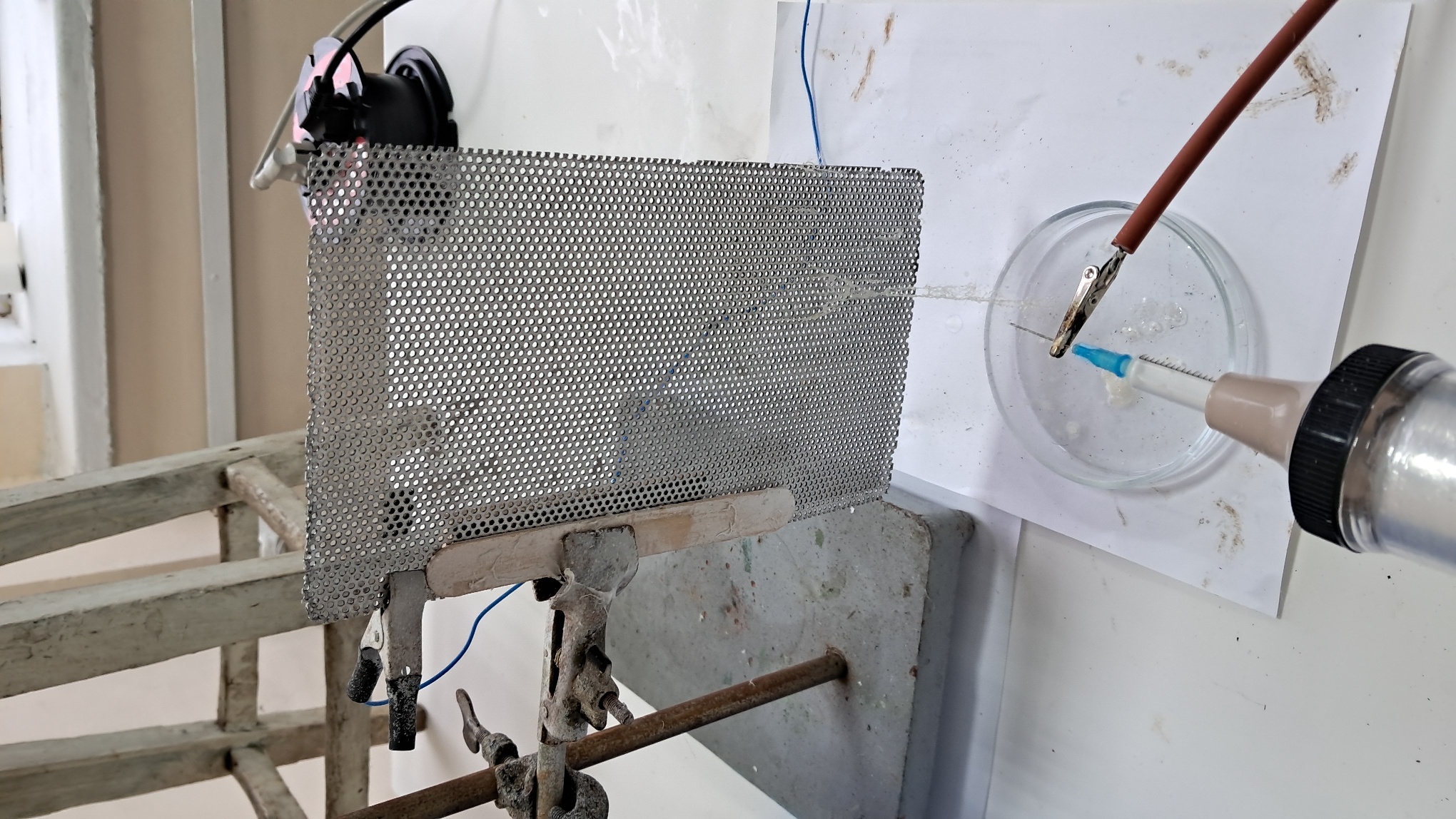

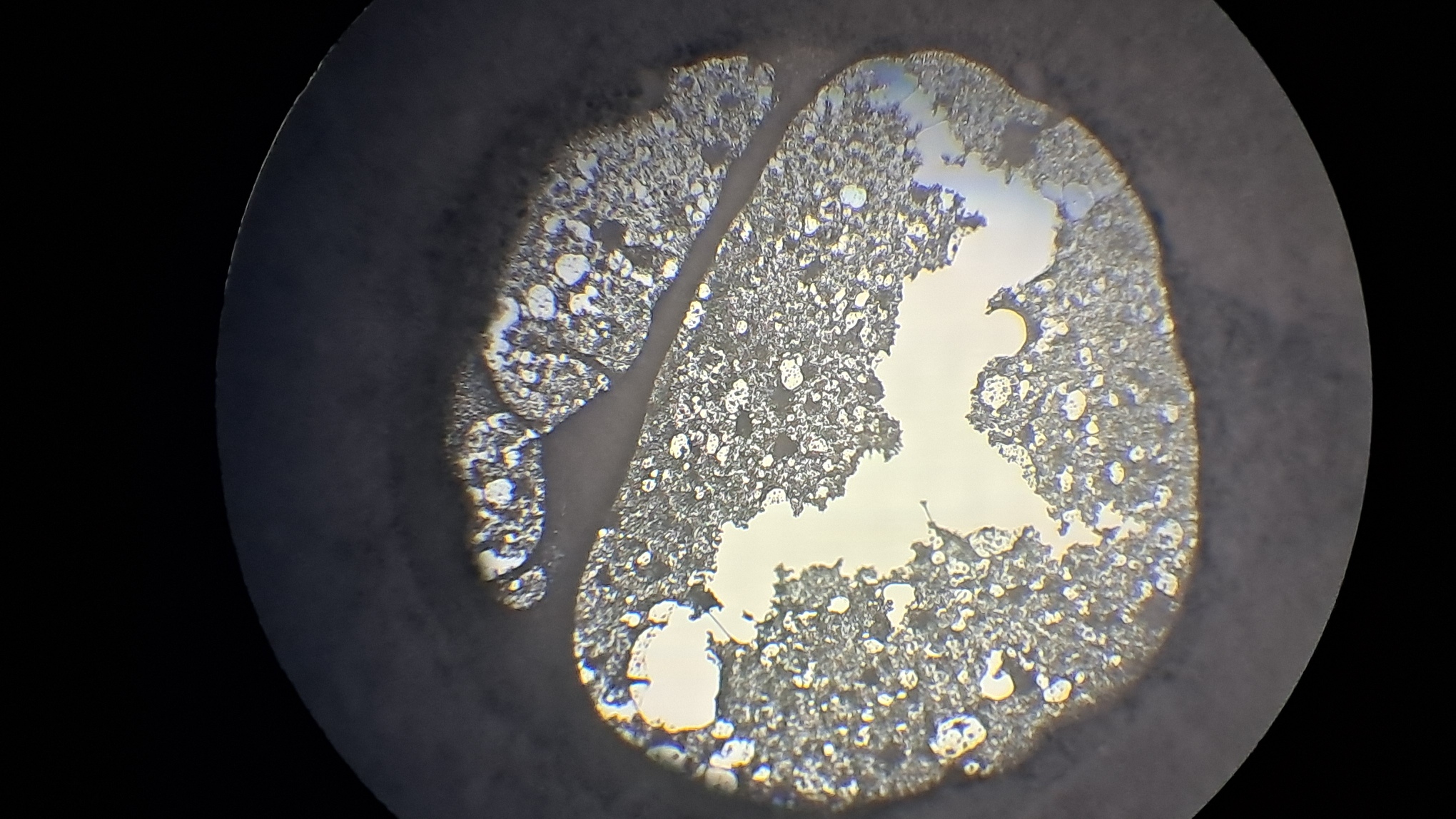

Электроспиннинг: раствор PVDF в DMF (окончание) - Часть 4 I called my colleague. He said that the pump had worked properly the last time it was used, but that had been a long time ago. "Try lubricating the mechanism." "You know I'm not good with mechanics - I could easily break it. I'll ask our mutual colleague." My chemist colleague lubricated the pump with oil, but this did not help. By the next day, however, there were puddles of oil on the laboratory bench. Then he brought in a jar of… nitrilotris(methylene)triphosphonic acid [ATMP or aminotris(methylenephosphonic acid)]. I asked: "What are you planning to do with this acid?" "Dissolve it in isopropanol and remove the rust from the pump parts!" "How do you know that this acid removes rust?" "It forms a strong complex with iron!" "Of course it does. But that doesn't mean nitrilotris(methylene)triphosphonic acid removes rust, nor does it mean that it won't dissolve the metal itself. Have you read anywhere that this acid is used for rust removal? And does it even dissolve in isopropyl alcohol?" "I haven't read about it. It dissolves in water, so it should dissolve in isopropyl alcohol as well. If you don't want me to use this acid, I also have a hydrocarbon-based rust remover." He handed me the bottle. I took a magnifying glass and read the label. It turned out that the product was an aqueous solution of phosphoric acid with an additive - apparently hexamethylenetetramine, serving as a corrosion inhibitor. The hydrocarbon solvent was mentioned on the label in a different context: "Before using the rust remover, degrease the surface with an organic solvent..." Annoyed, I said: "Did you even read the label before buying this? It's just aqueous phosphoric acid." My colleague replied: "We can't use phosphoric acid - it could damage the mechanism. I'll look through some books about using nitrilotris(methylene)triphosphonic acid instead." The next day, he announced that nitrilotris(methylene)triphosphonic acid is indeed used to remove rust and that he would try to repair the syringe pump. A month has passed since then, and the pump is still broken. He has not even touched it. The jar of nitrilotris(methylene)triphosphonic acid remains somewhere in his laboratory. I am sure that my physicist colleague could have repaired the pump quickly, but he was seriously ill and out of action for a long time. I therefore had to continue experimenting with the existing syringe pump. At that time, I was doing electrospinning every day, although I changed the object of my experiments. I began working with a different polymer and other solvents, which I will describe later. If PVDF in DMF was not working, I saw little point in repeatedly reproducing the same negative result - especially since neither of my colleagues could clearly explain why they needed PVDF fibers specifically, rather than, for example, polyethylene fibers. Nevertheless, along with the pump, my physicist colleague had given me two containers of a ready-made PVDF-in-DMF solution and asked me to try using it for electrospinning. Before working with this solution, I needed to determine the polymer concentration. The analysis was gravimetric: a sample of the solution had to be evaporated, and the mass of the dry residue determined. Around that time, the institute had purchased an analytical balance for my chemist colleague. I have been working as a chemist since 1998, but this was the first time I had seen an analytical balance bought for a chemical laboratory. Scientists and engineers usually relied on old scales - some of which were older than the specialists themselves. Since my colleague's laboratory was cluttered with absolute junk, he brought the balance to my lab and even assembled it. All that remained was to level the balance by adjusting the position of the air bubble. I asked him to do this, and he promised he would. The next day, while I was conducting an experiment, I heard some commotion outside the lab door. A colleague came in carrying… part of a table. "This is for the balance. I also need to bring the desk drawer." "I'll help you now," I said, "but first I need to clean the needle, otherwise the solution will solidify inside it." I was in a hurry and pressed the syringe plunger too hard; the needle came off, and a jet of solvent hit me in the face. To prevent such accidents, experienced chemists advise always holding the needle against the syringe with one's fingers. After all, the syringe might not contain DMF, as it did in my case, but a far more dangerous substance. We went down five floors to a colleague's room. I saw the desk drawer - it looked terrible. My colleague had not warned me that he intended to bring the entire table into my laboratory. We had only discussed the need to place the analytical balance on a stone slab with a stable support. The table on which the balance currently stood was sagging and clearly unsuitable for precise weighing. If my colleague had his way, he would fill my laboratory with unnecessary objects as well, until it became unusable. He had already turned his own lab into an impassable warehouse. Quietly, I said: "Leave me alone." I returned to my laboratory and continued the experiment. Later, I asked a neighboring geologist to adjust the balance. He was not enthusiastic, but he agreed. After adjustment, it turned out that the nominal masses of the calibration weights supplied with the old balance did not match the readings on the new one. I could not tell whether the problem lay with the balance or with the weights, so I performed the analysis using an old technical scale with an accuracy of 0.005 g. Of the three parallel determinations, the first failed, the second gave 10.2%, and the third 10.1%. I called my physicist colleague and told him the results. He replied that the solution was indeed 10% - he already knew this - but he had been concerned that some solvent might have evaporated during long-term storage. Much later, while selecting photographs to illustrate an earlier part of this article, I noticed that the composition of the solution was written on one of the bottles. I invited my chemist colleague over and began experimenting with the PVDF solution. The start was very encouraging. The solution emerging from the needle tip formed a "foggy cone" - exactly the kind of cone my colleagues had previously described. One of them was present and insisted that these were fibers. From the surface of the collector electrode toward the needle, white "dendrites" grew and branched. They resembled videos of plant growth shown in accelerated time. I had already observed similar dendrite-like structures in parallel experiments with a different polymer and different solvents. In those experiments, incidentally, the dendrites always grew from the needle tip toward the collector, not in the opposite direction. I could not determine whether the "fog cone" consisted of fibers or aerosol particles until I finished the experiment and examined the deposited material under a microscope. Unfortunately, I found no fibers - the coating consisted of agglomerated particles of irregular shape. In the next experiment, I replaced the aluminum foil with a perforated aluminum mesh and changed the orientation of the setup from horizontal flow to vertical, from top to bottom. This also failed. Instead of fibers, a yellow, slime-like mass accumulated on the collector. When I tried to examine it under a microscope, I contaminated the microscope stage. I then increased the polymer concentration to 15% and 20% by adding solid polymer to the existing solution, but this did not lead to success either. One possible explanation for the failure is the high boiling point of DMF (153°C): the solvent simply does not evaporate quickly enough during electrospinning. Even if fibers initially form, they may coalesce on the collector into a semi-liquid mass. On the other hand, my colleagues had managed to produce fibers earlier. However, they had used a different monitor and a different polymer solution. In addition, they were working in the summer, whereas it was now winter, and the laboratory was cold. In the following parts, I will describe parallel experiments that I carried out using polystyrene. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A small corona discharge |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|