Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2026

Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts

| Content | Chemistry experiments - video | Physics experiments - video | Home Page - Chemistry and Chemists |

|

Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2026 Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts |

Electrospinning - pt.5, 6 Chemist |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

Electrospinning: Solution of Polystyrene in Surrogate Acetone (Trial Experiment) - Part 5

A prolonged lack of positive results is demoralizing for a researcher, especially when one starts in an unfamiliar field. If I had previously successfully produced fibers using electrospinning, I could now compare past successful experiments with the current unsuccessful ones to find and fix the problem. However, I had no previous experience, so all I could do was read the literature, consult with colleagues, and plan and conduct experiments on my own.

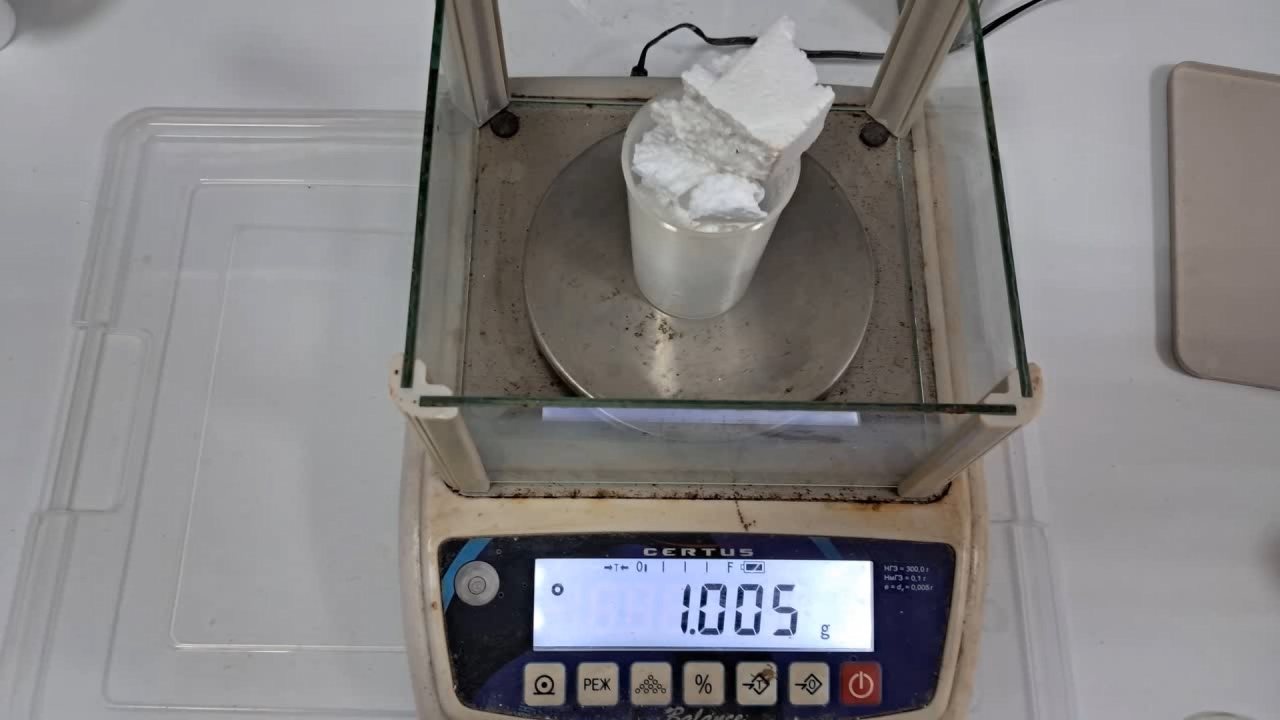

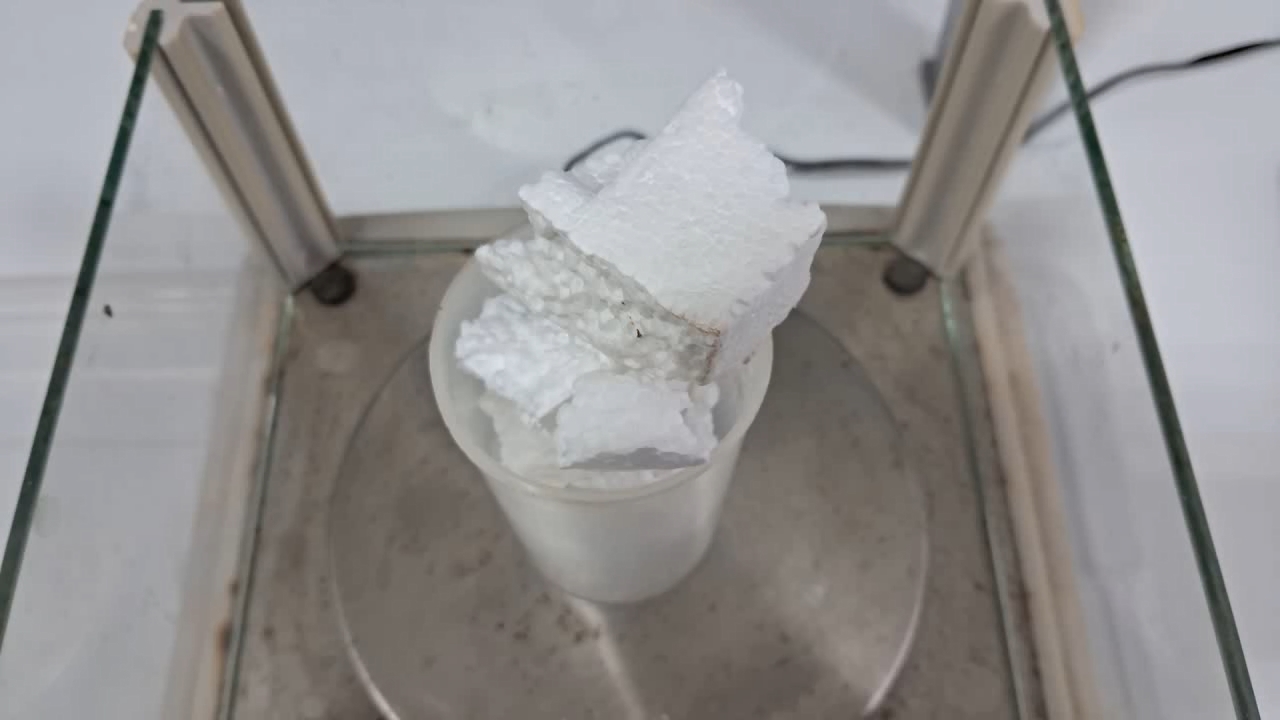

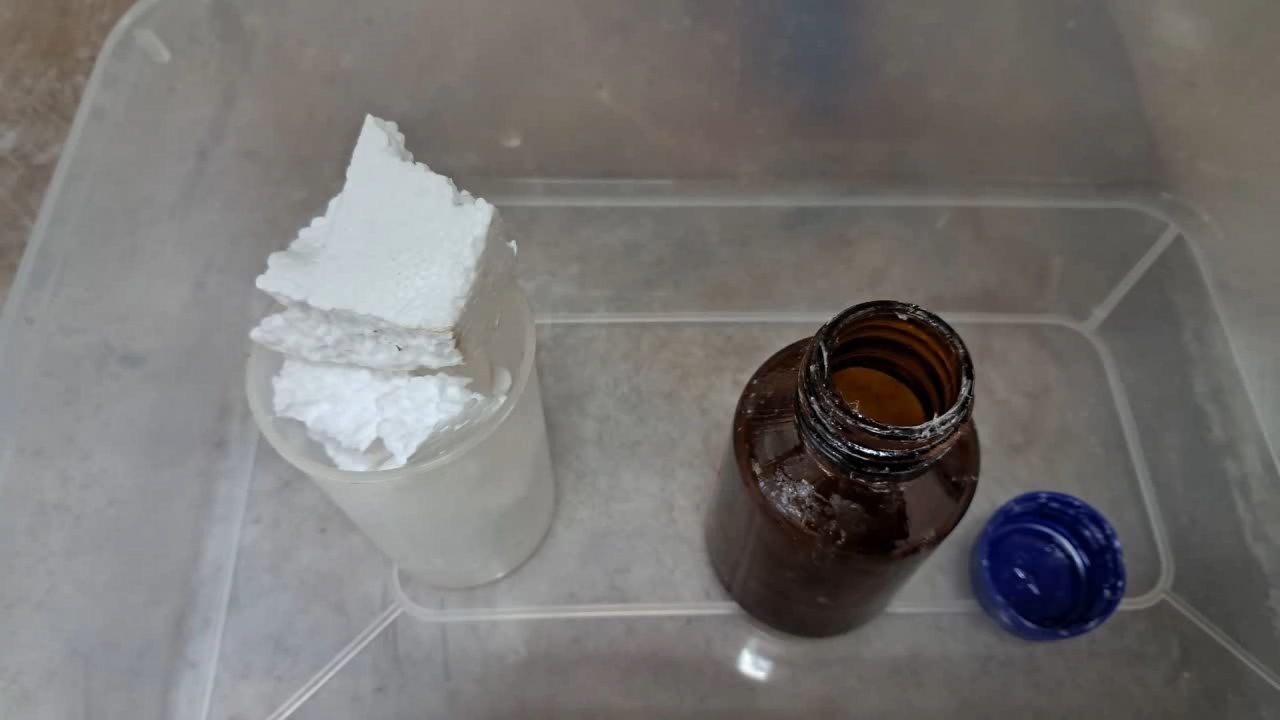

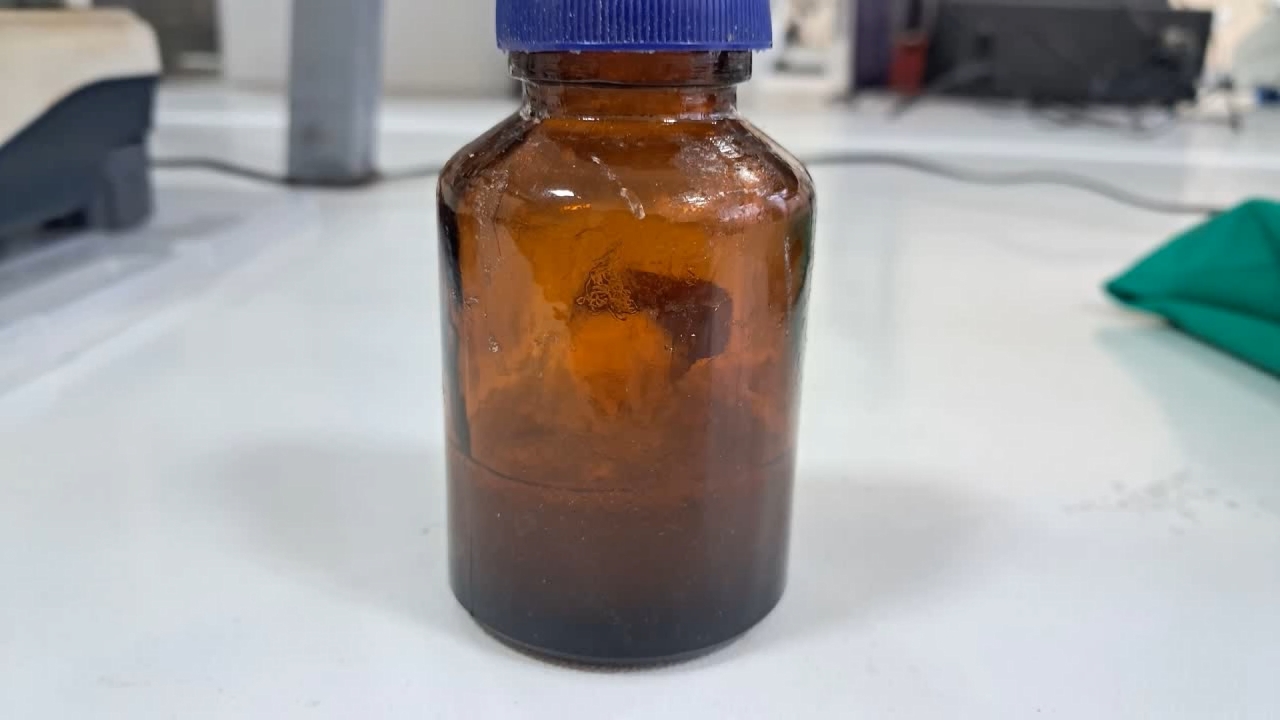

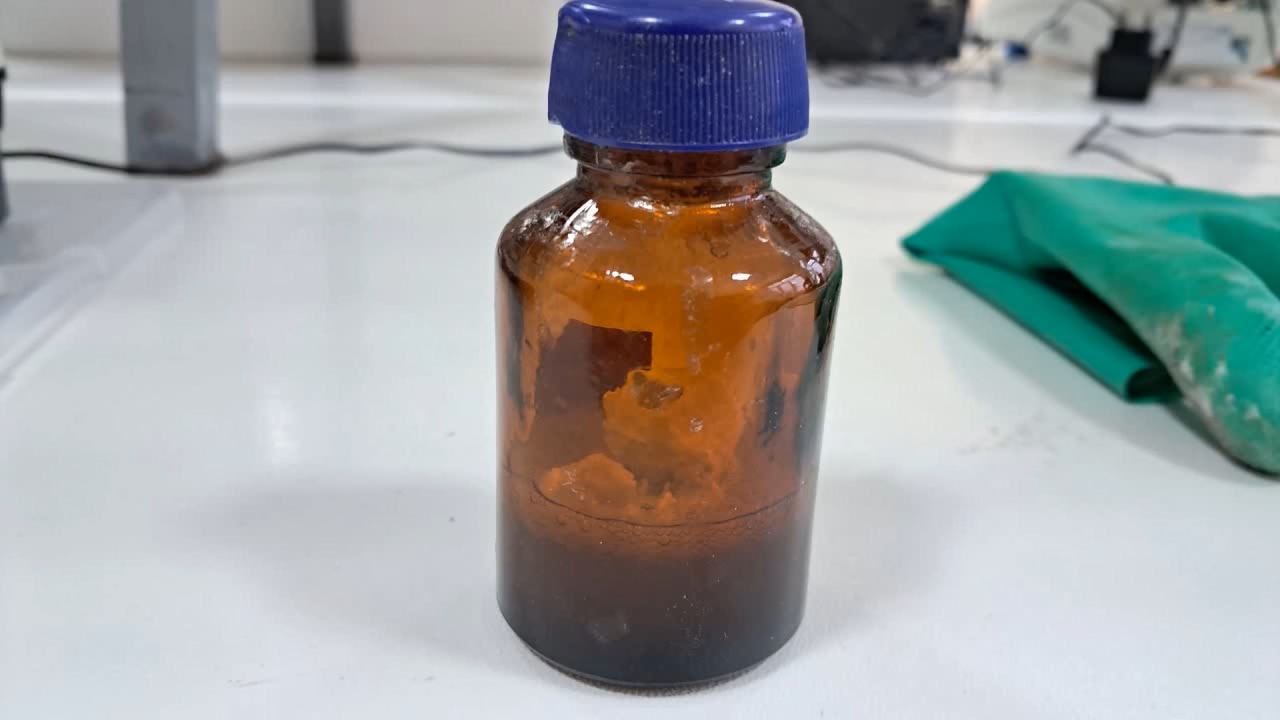

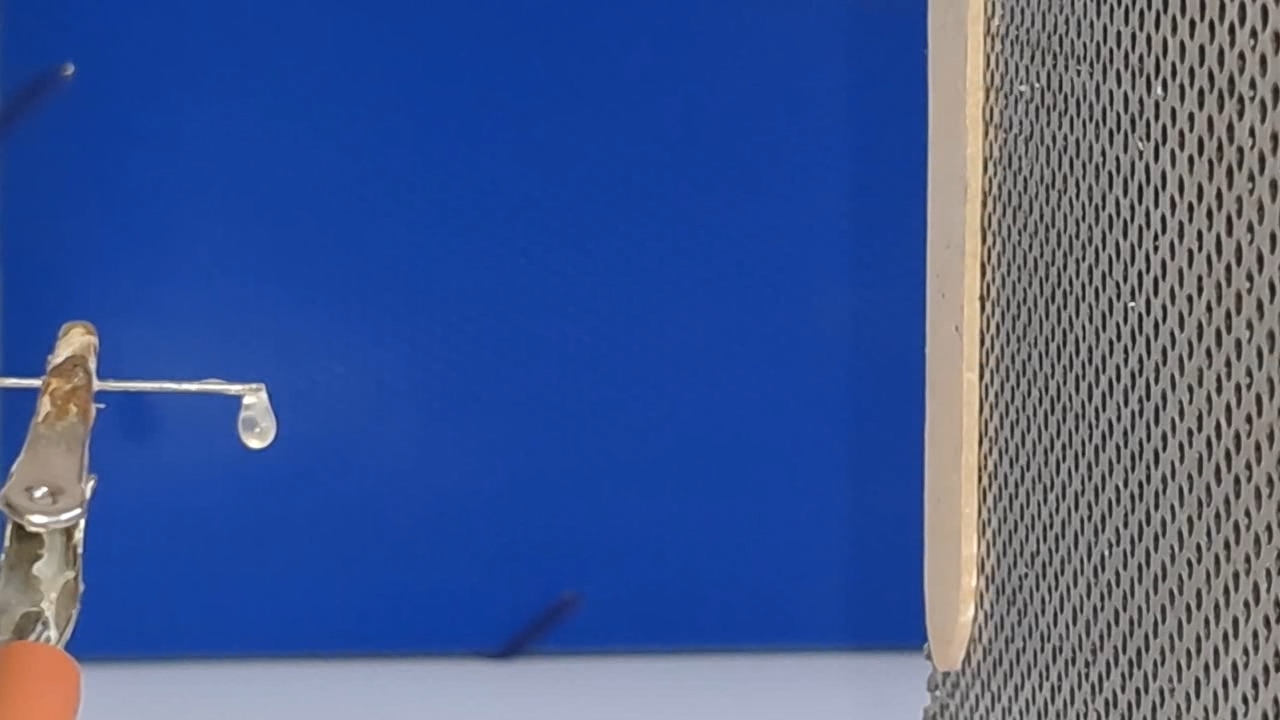

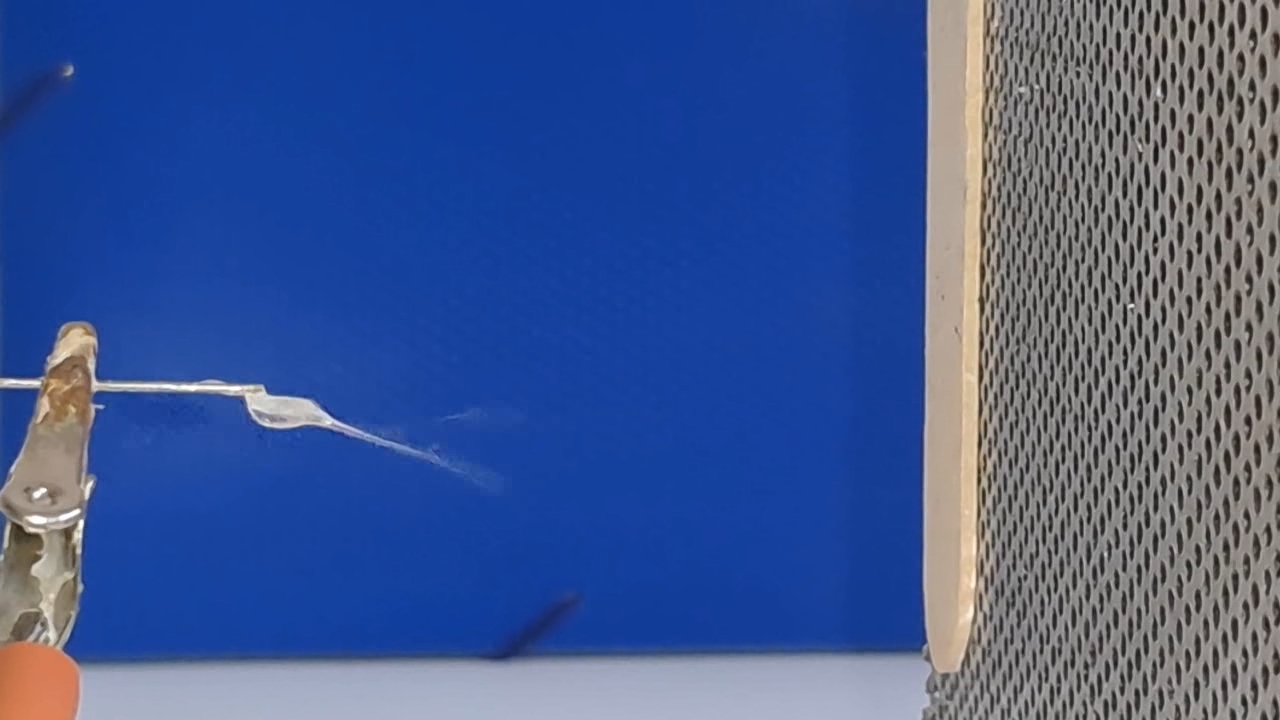

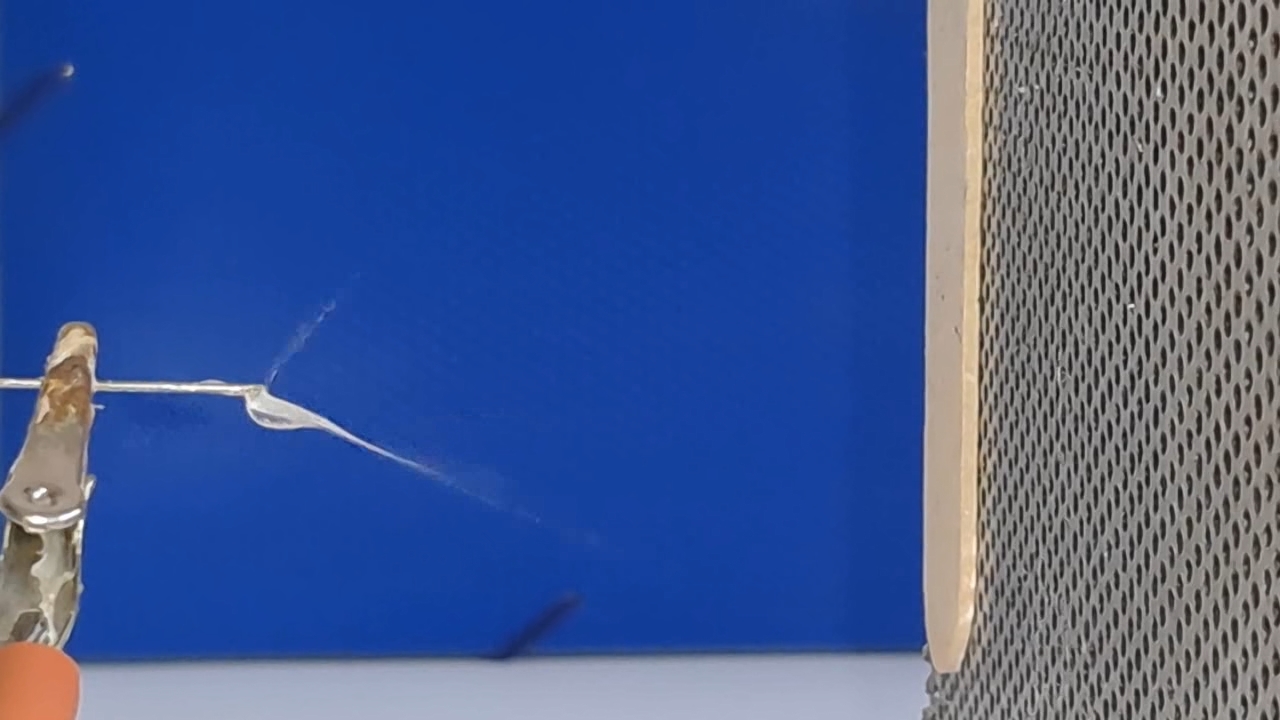

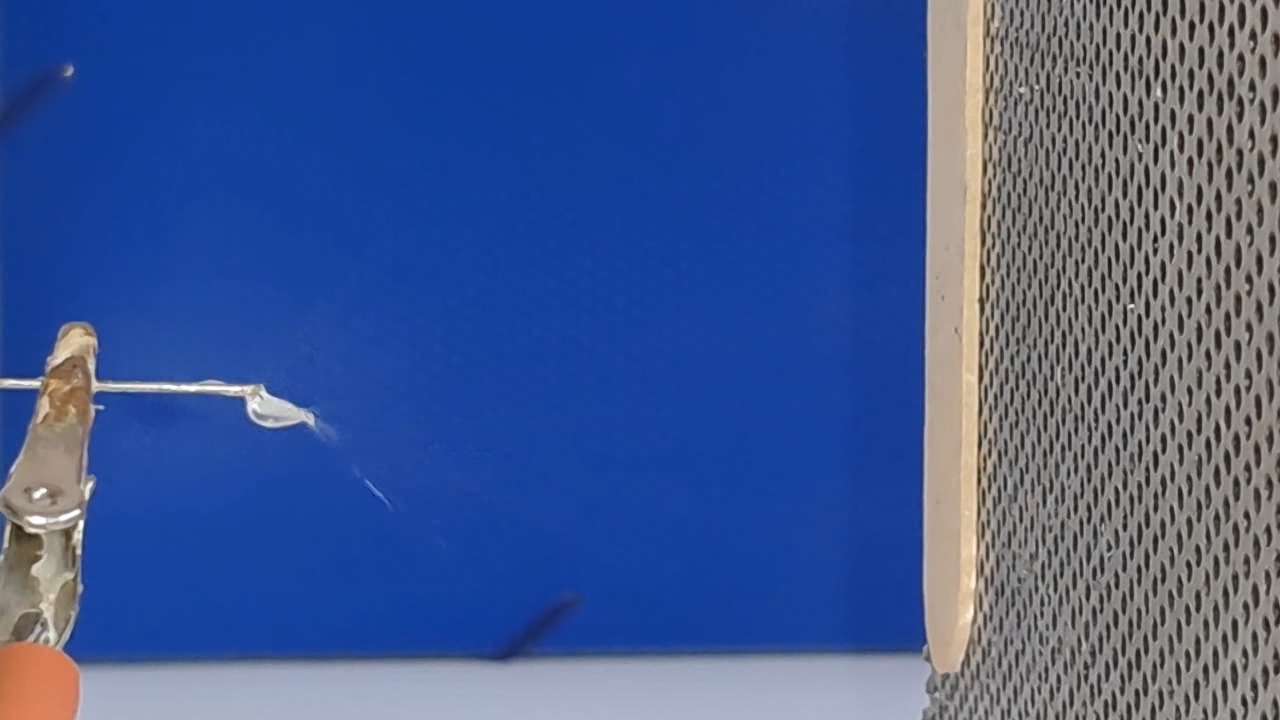

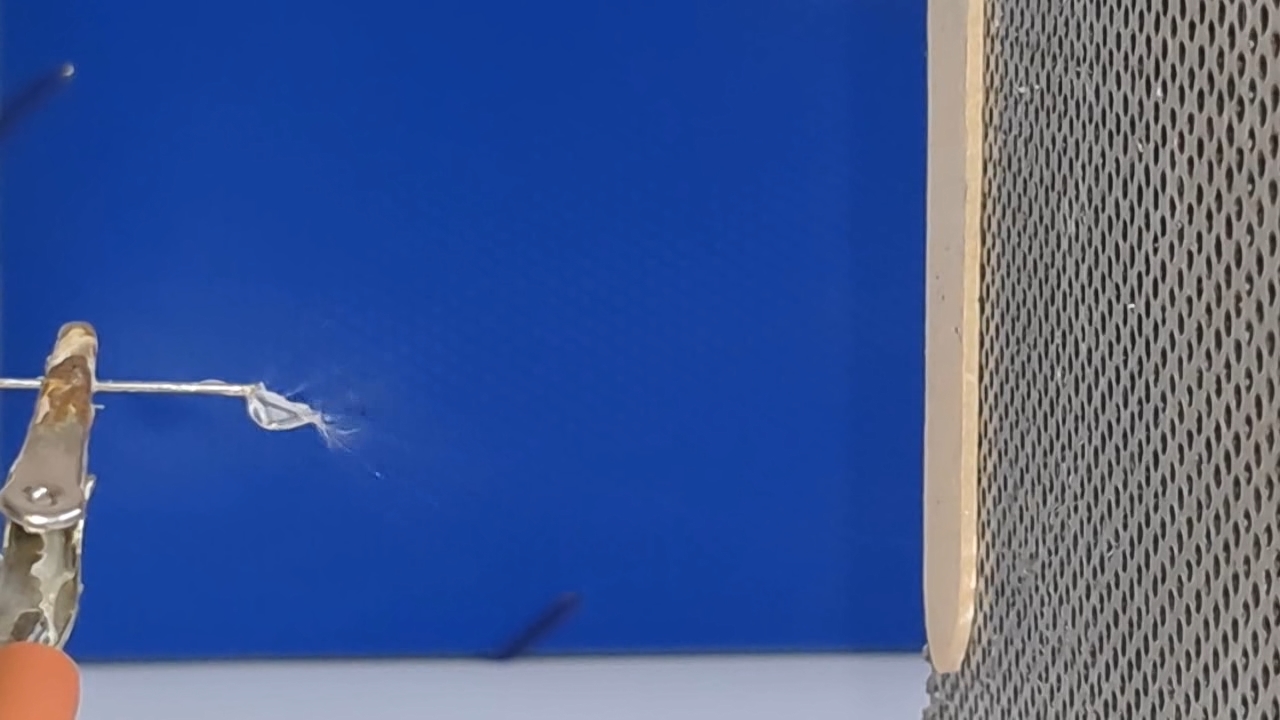

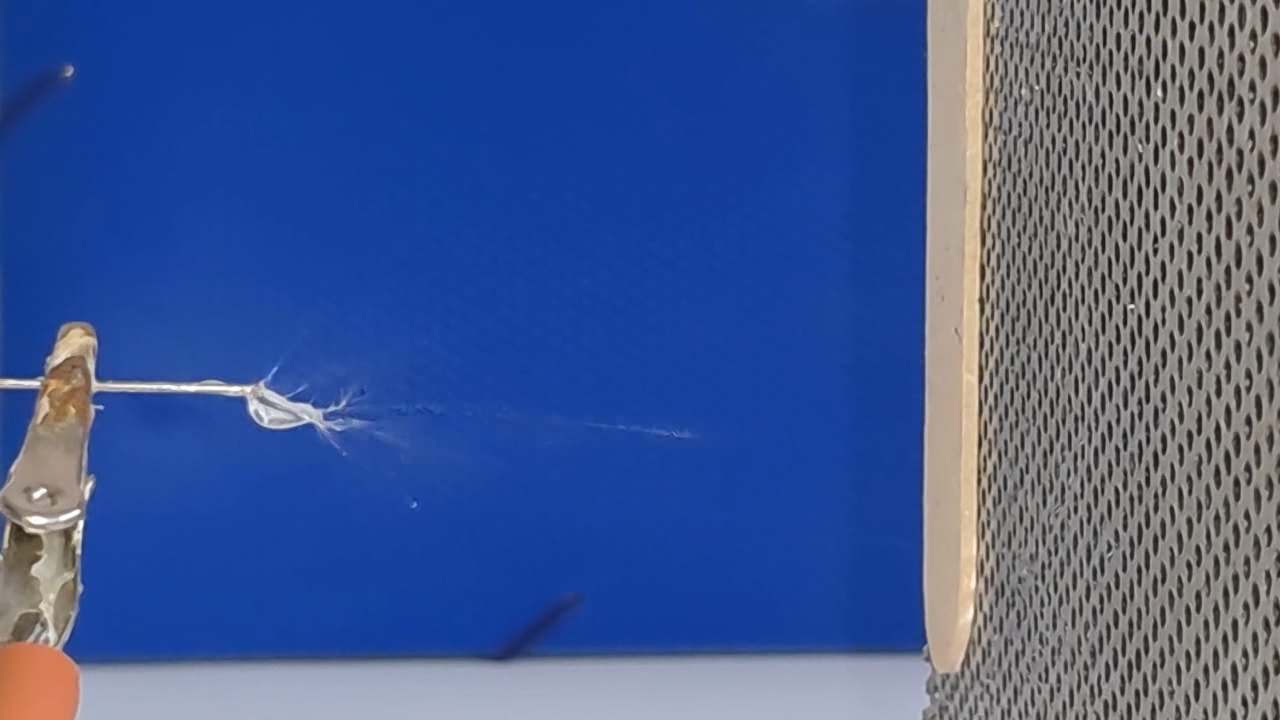

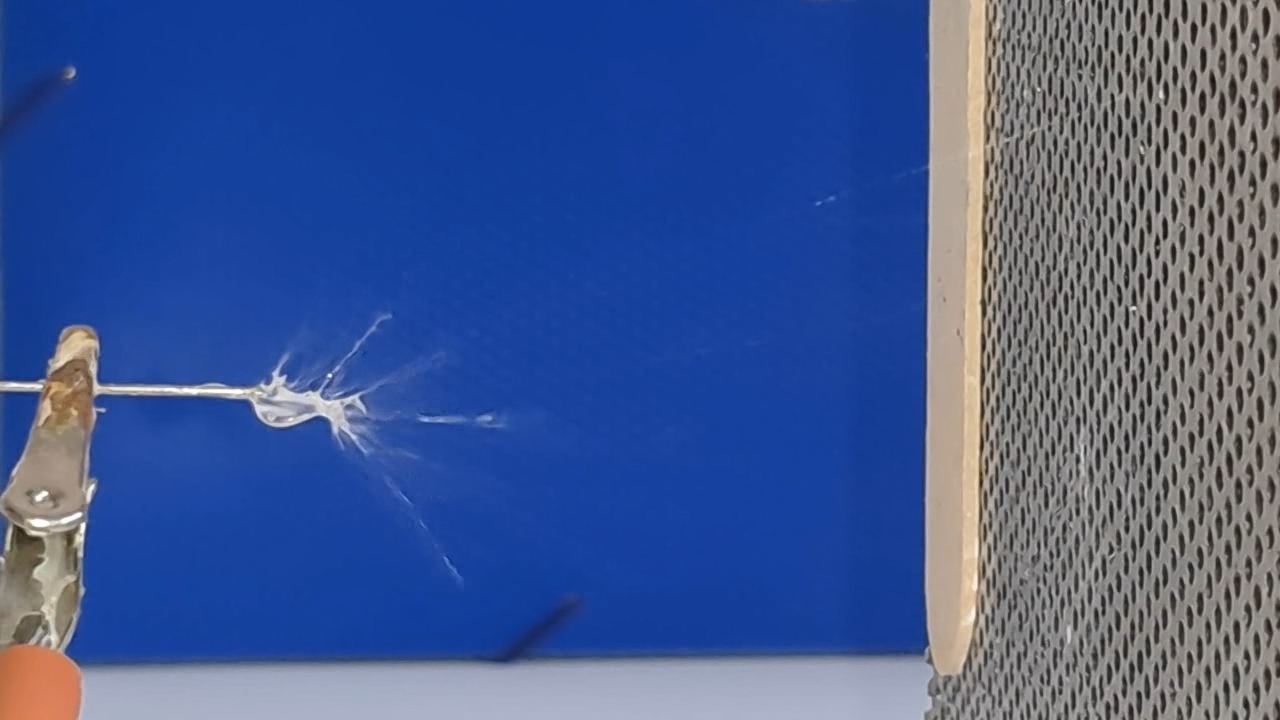

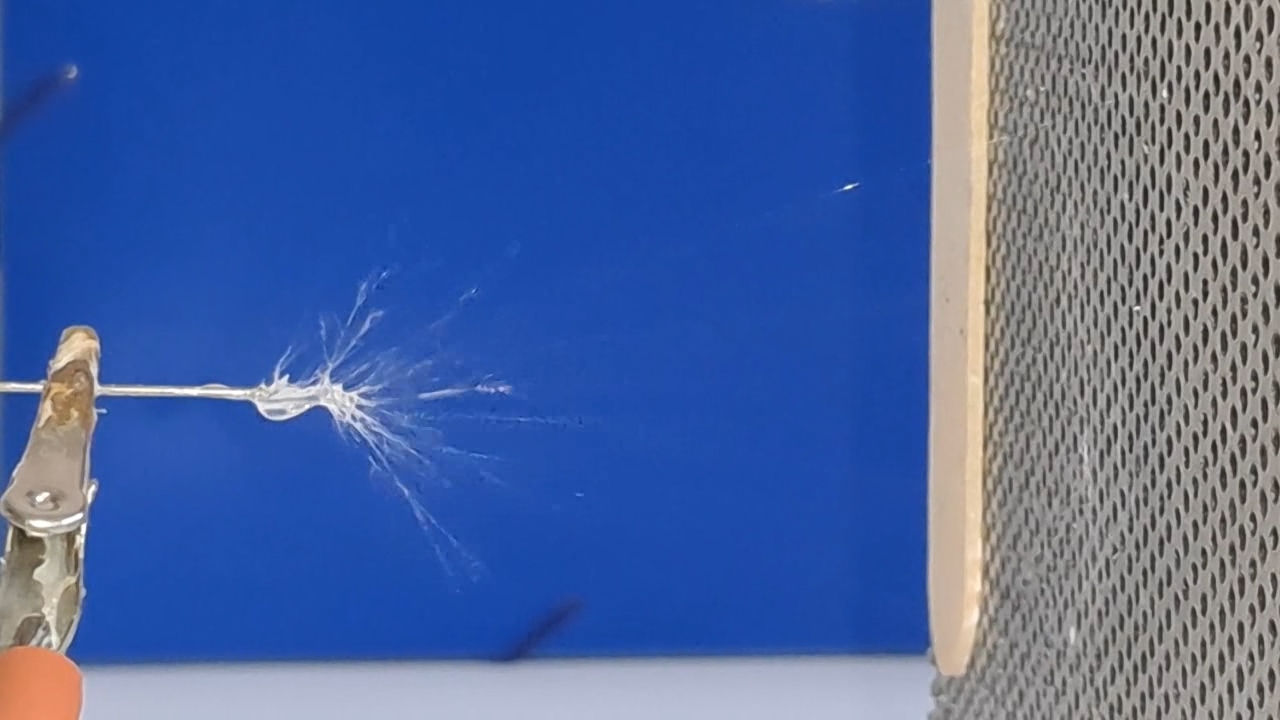

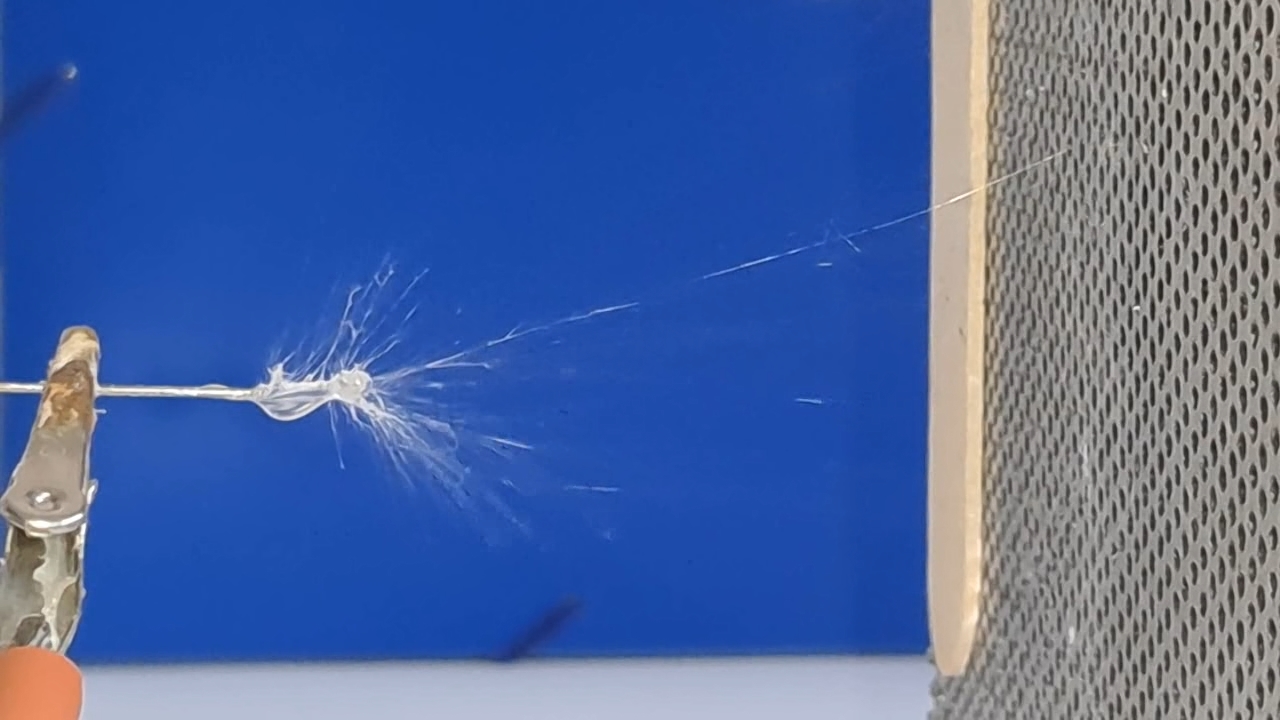

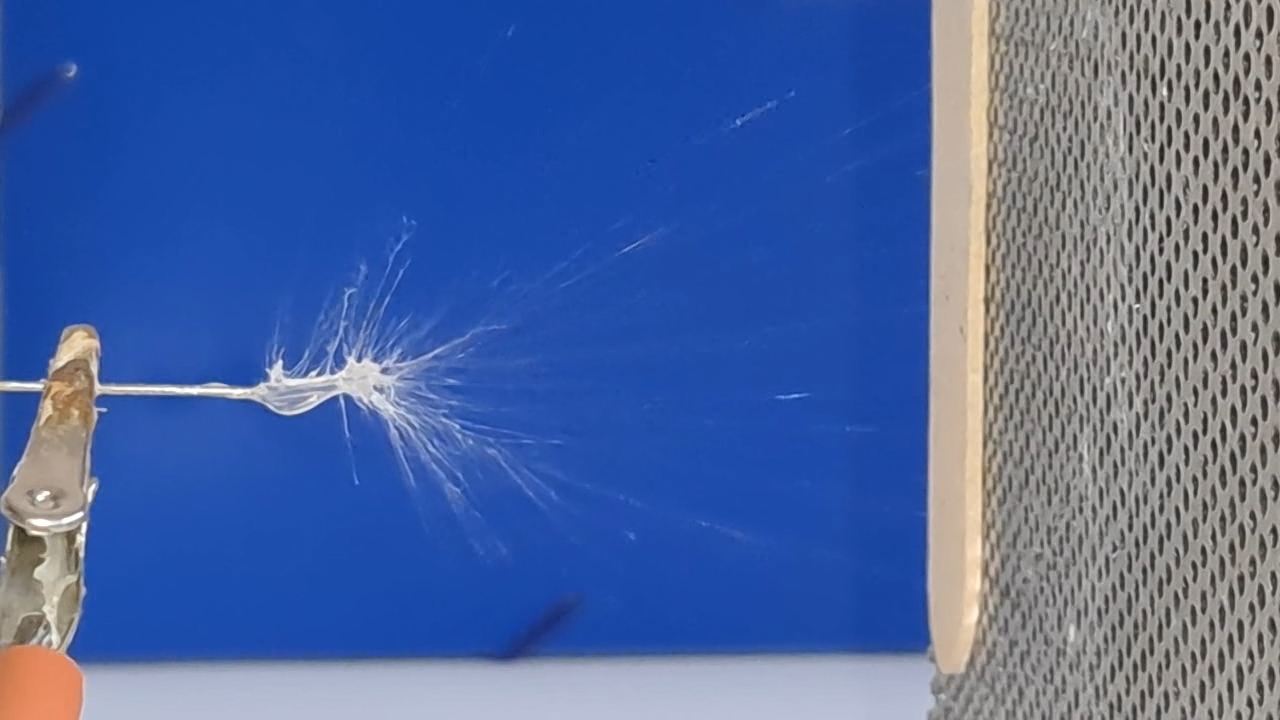

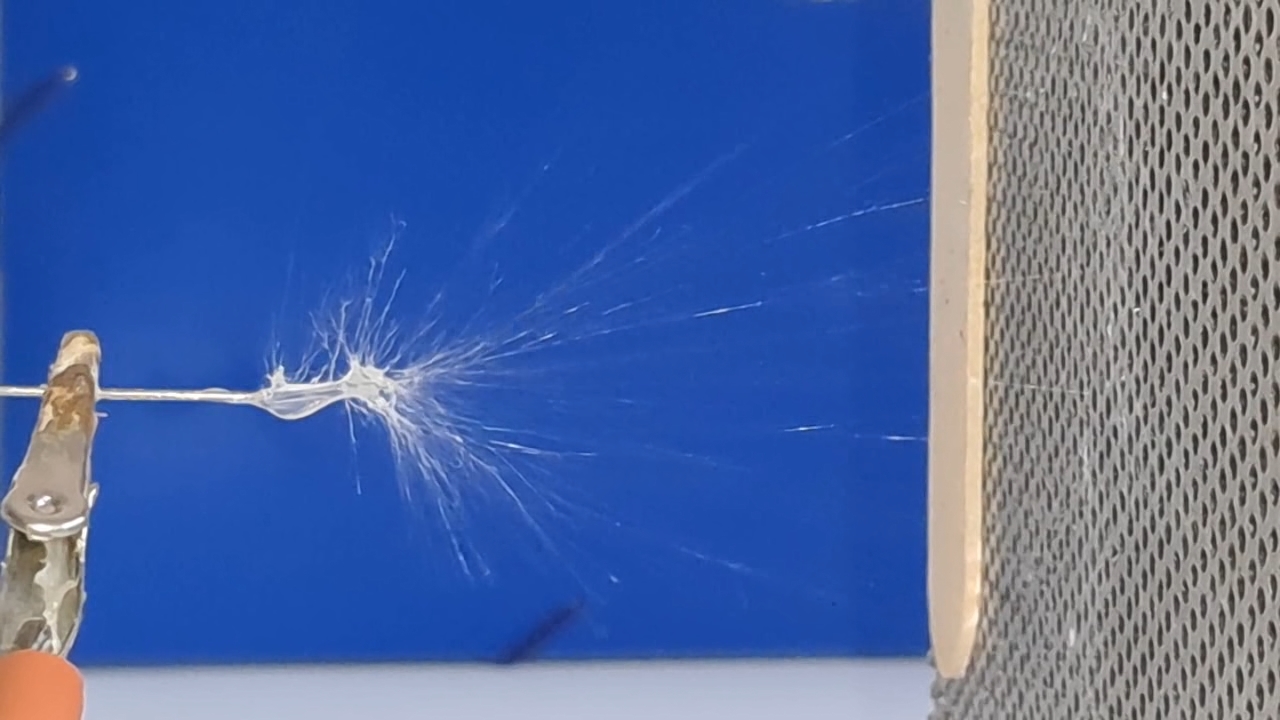

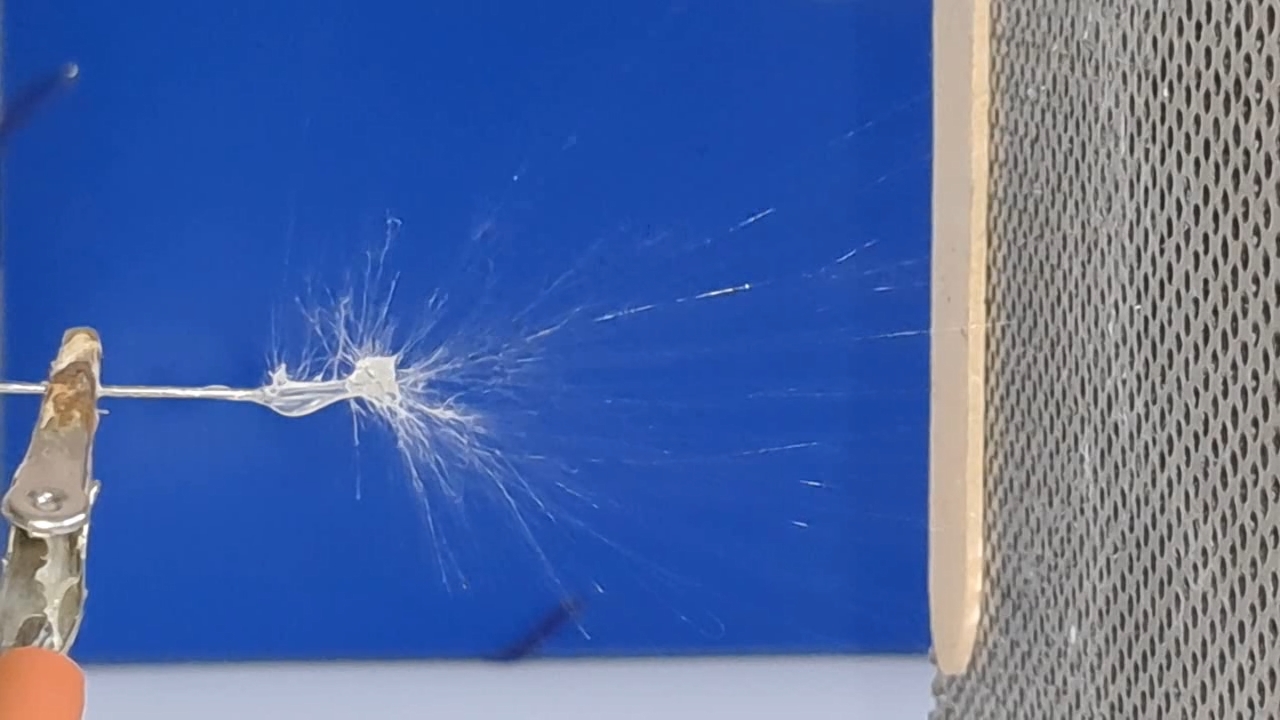

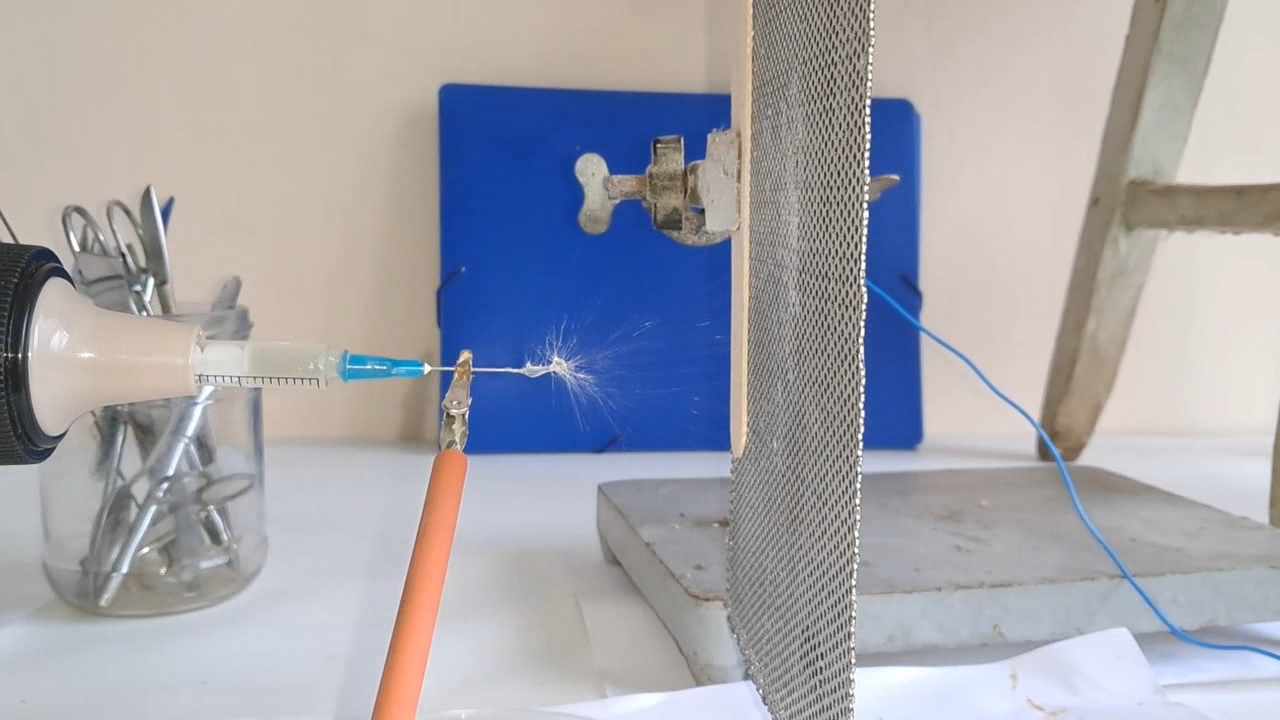

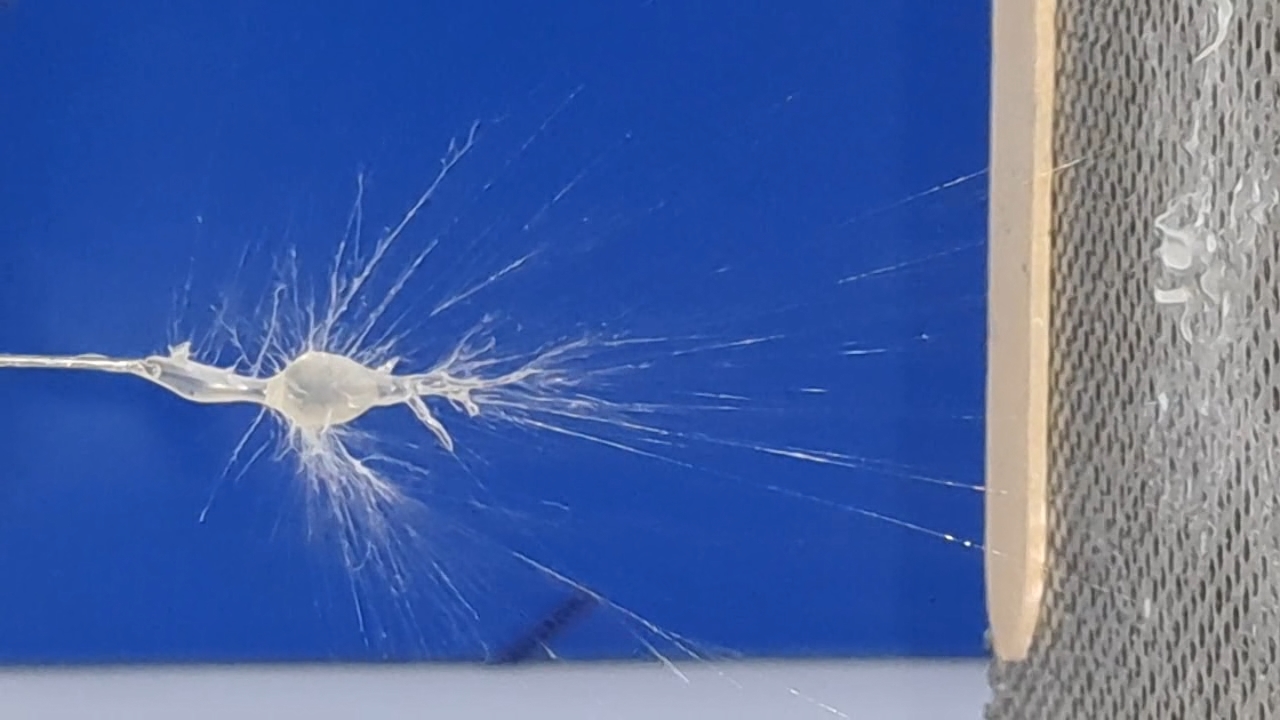

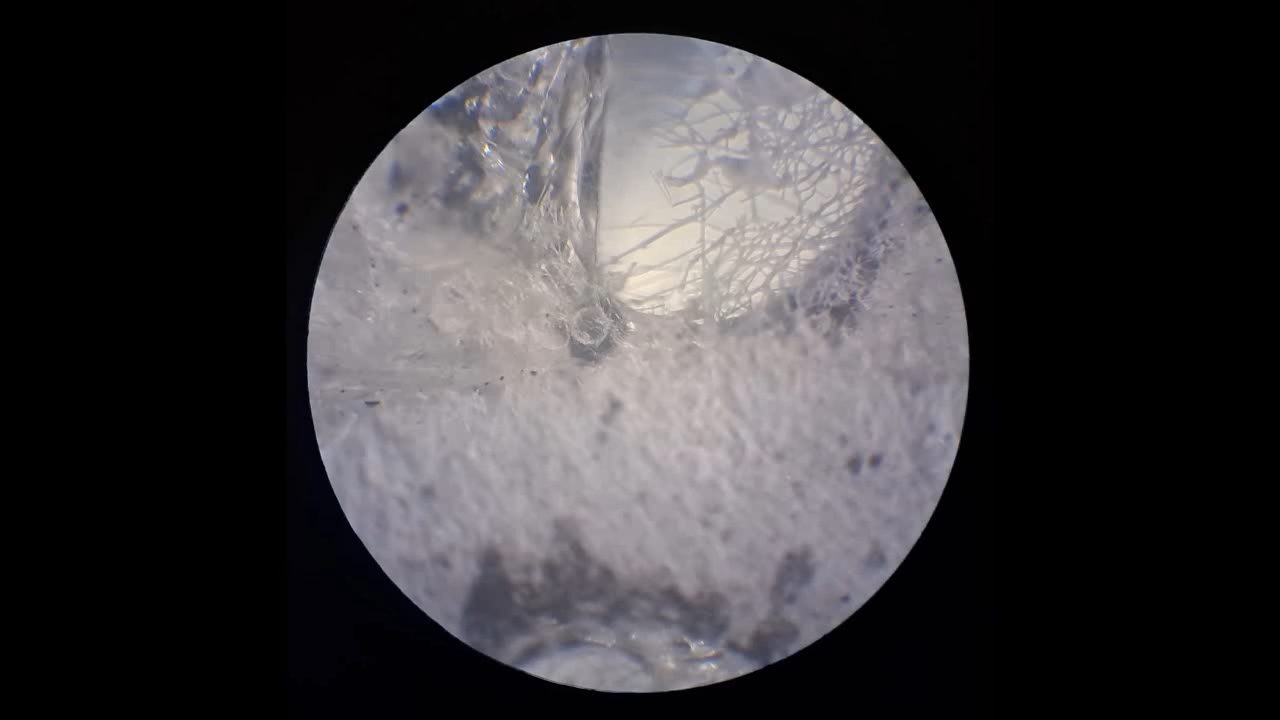

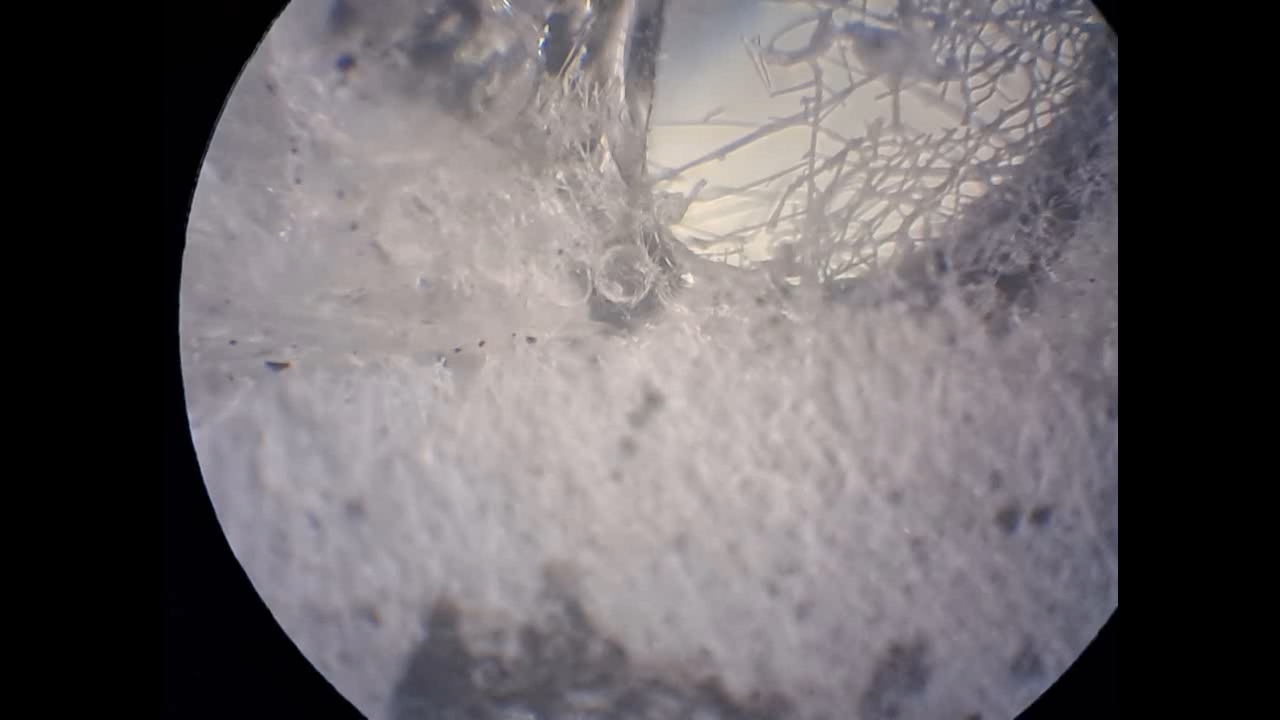

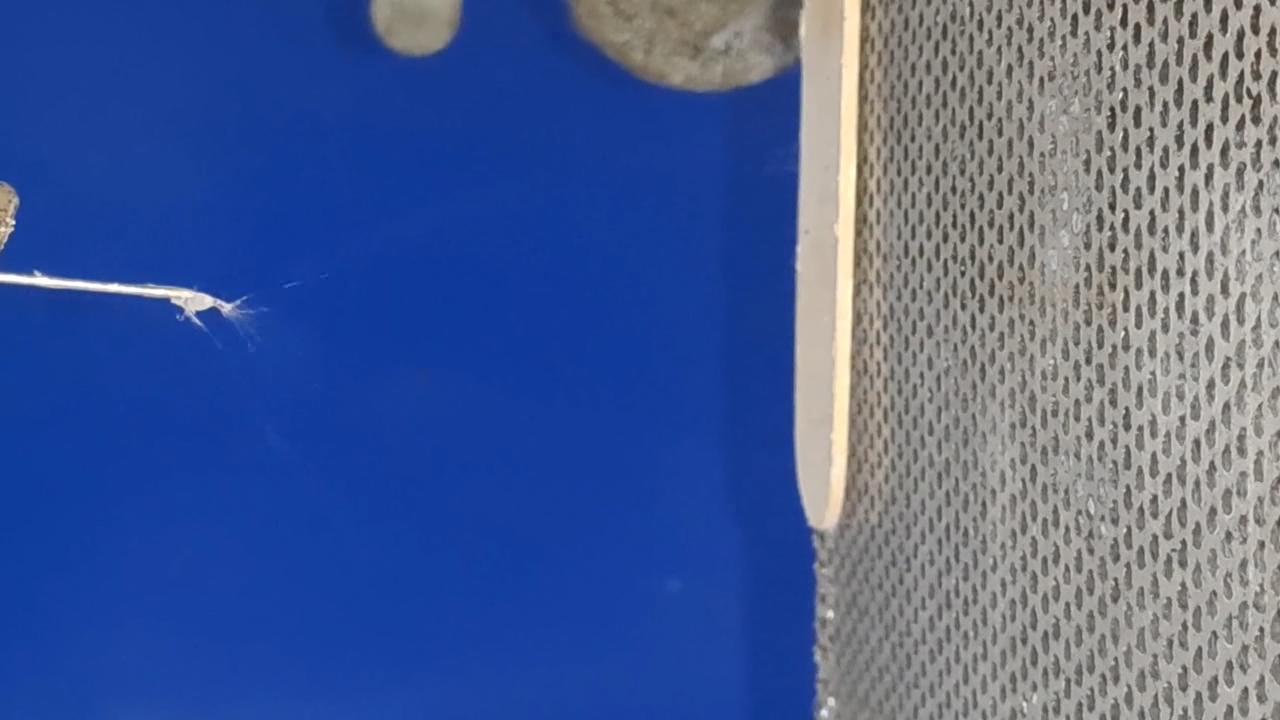

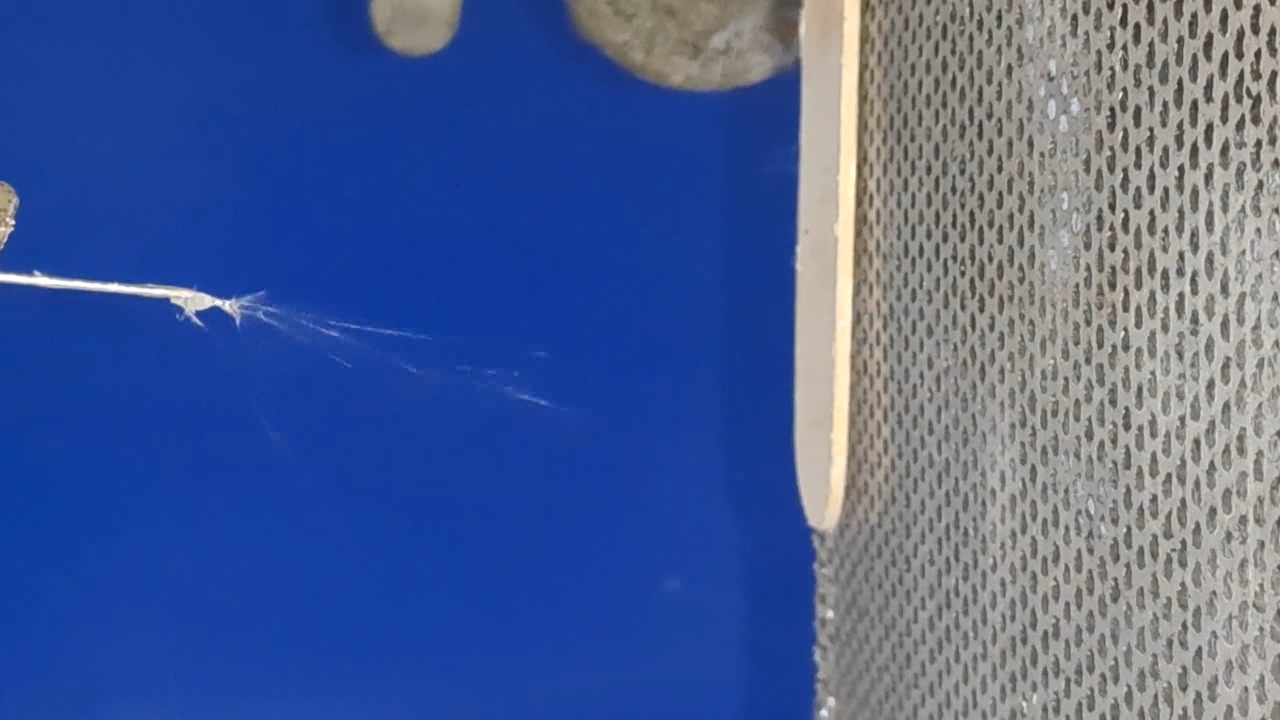

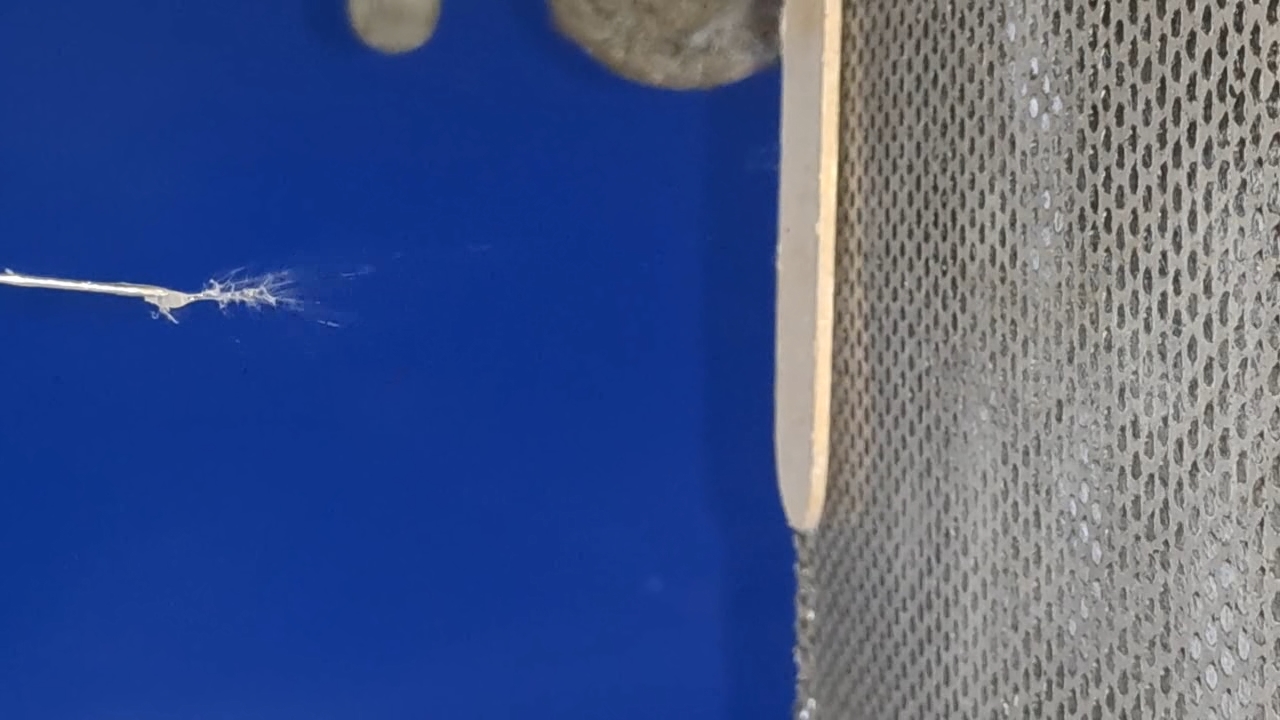

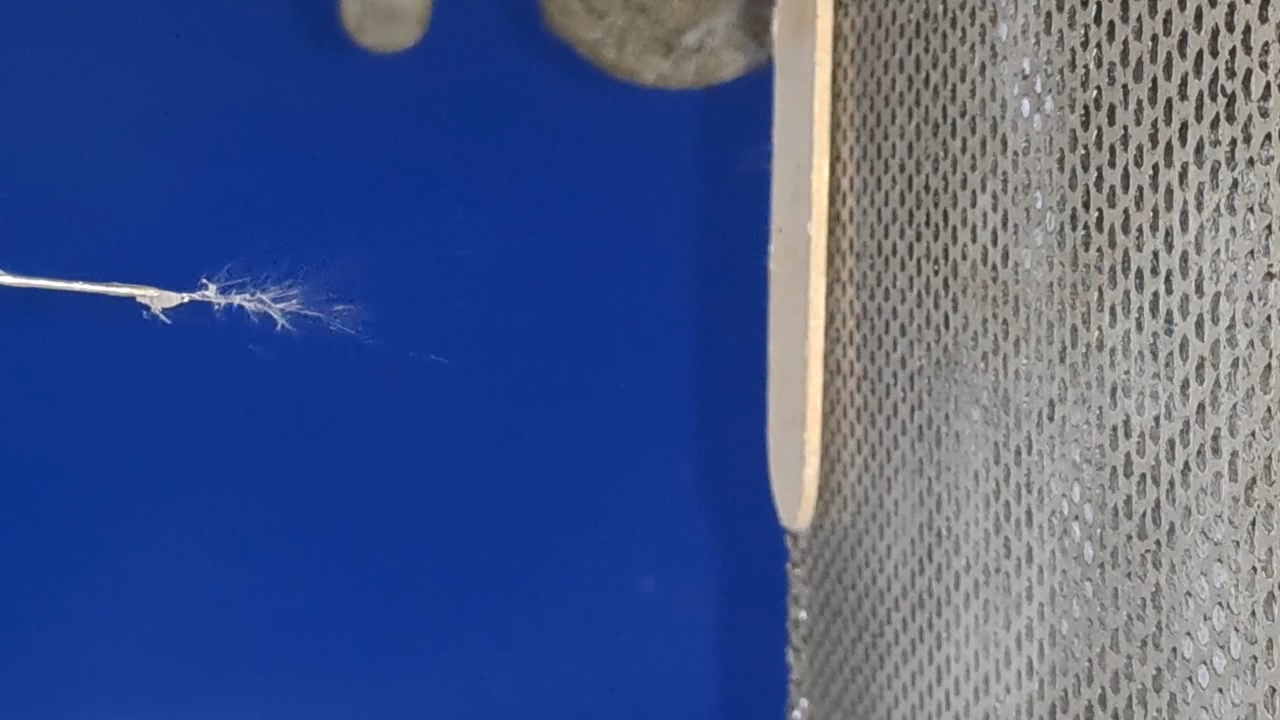

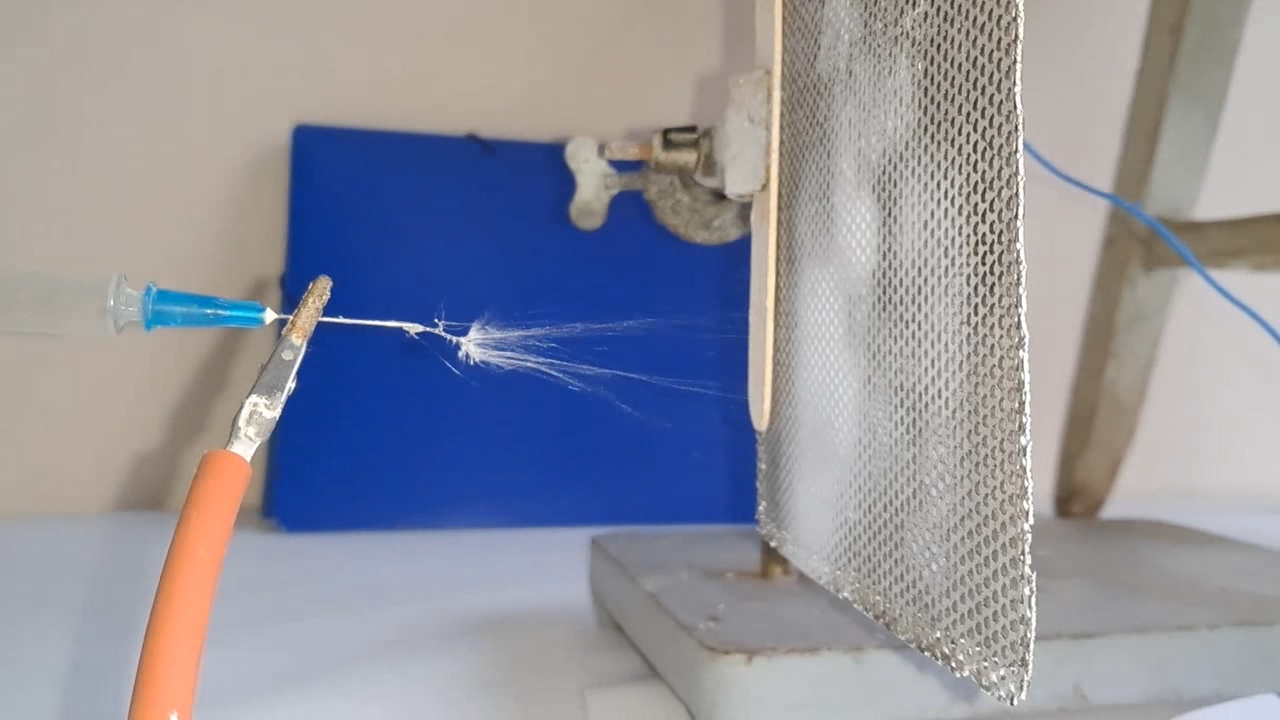

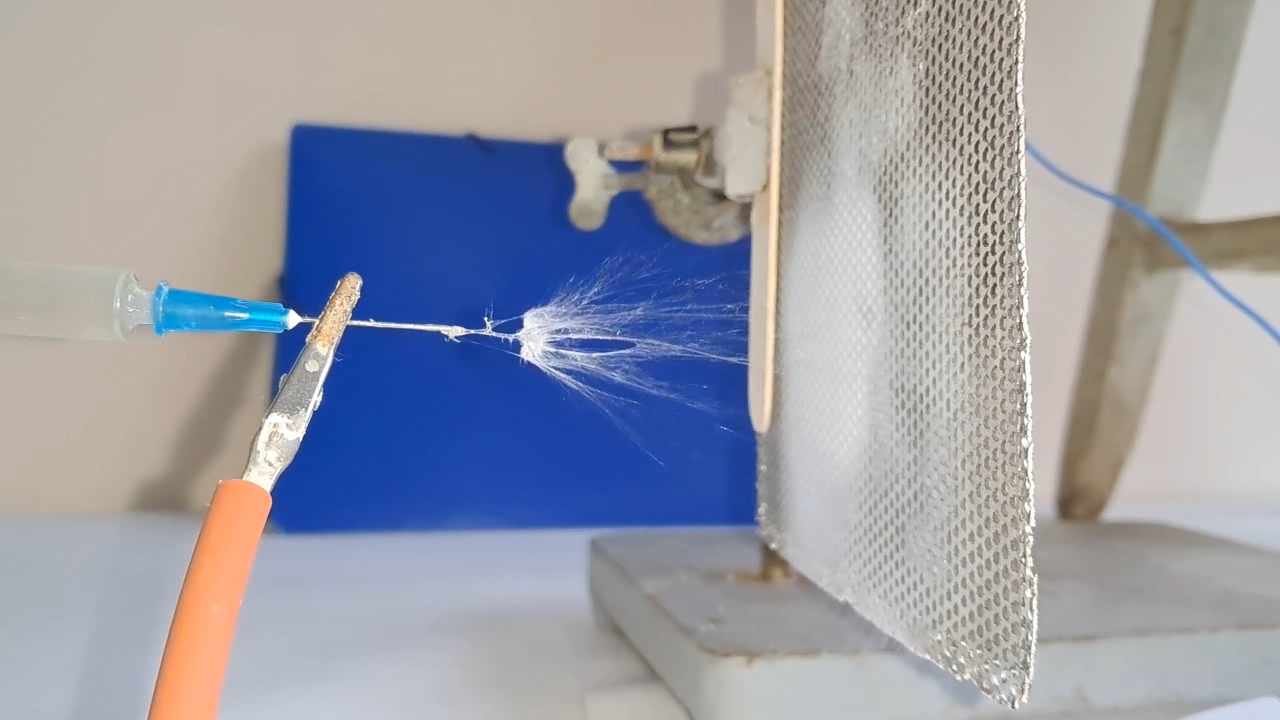

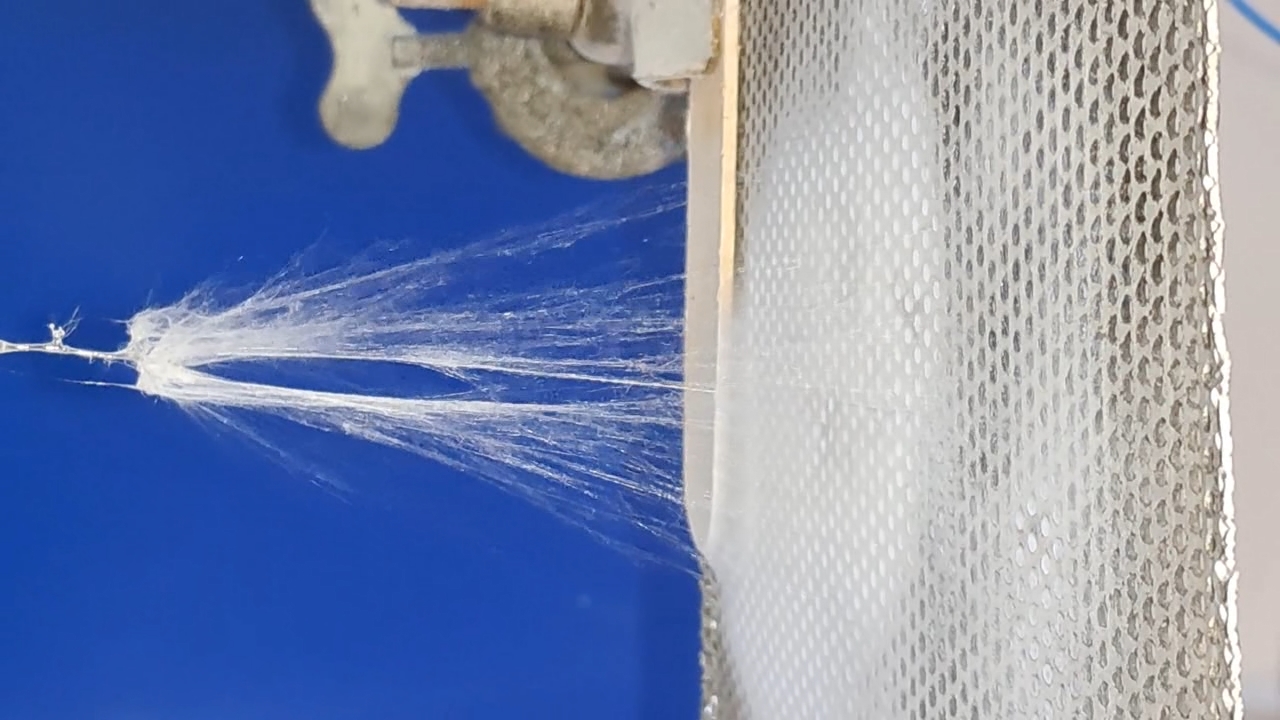

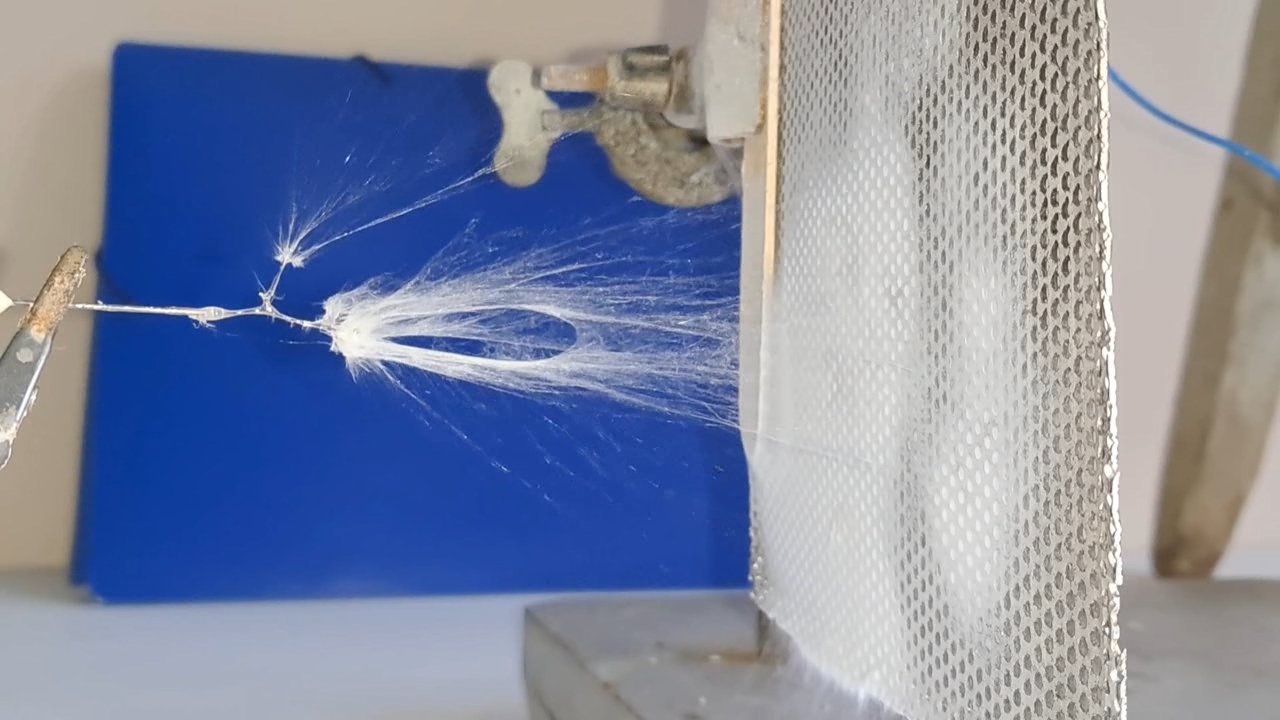

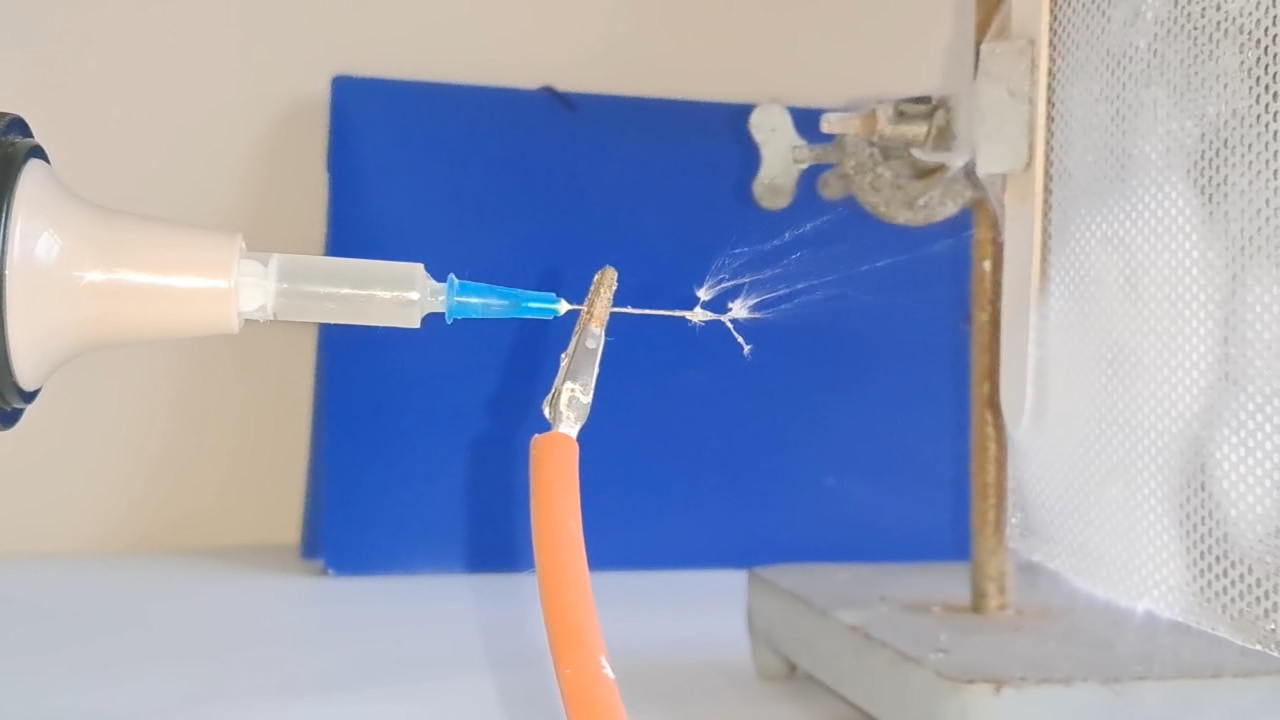

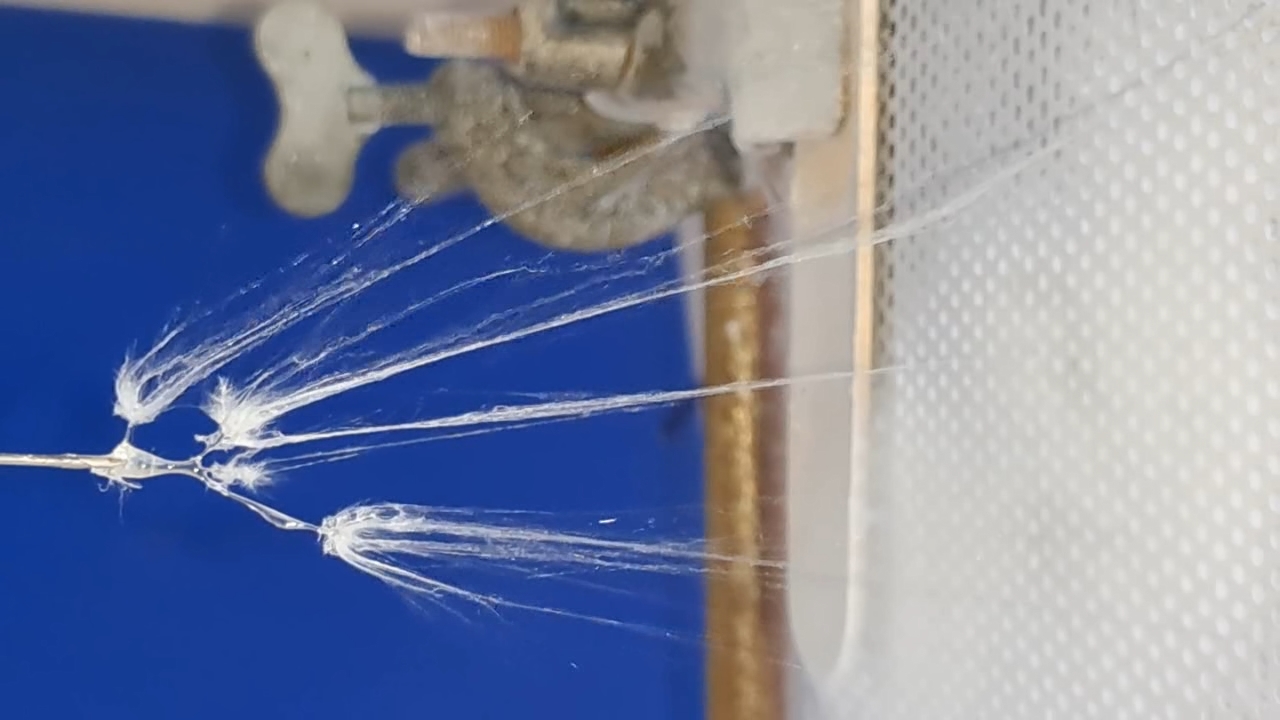

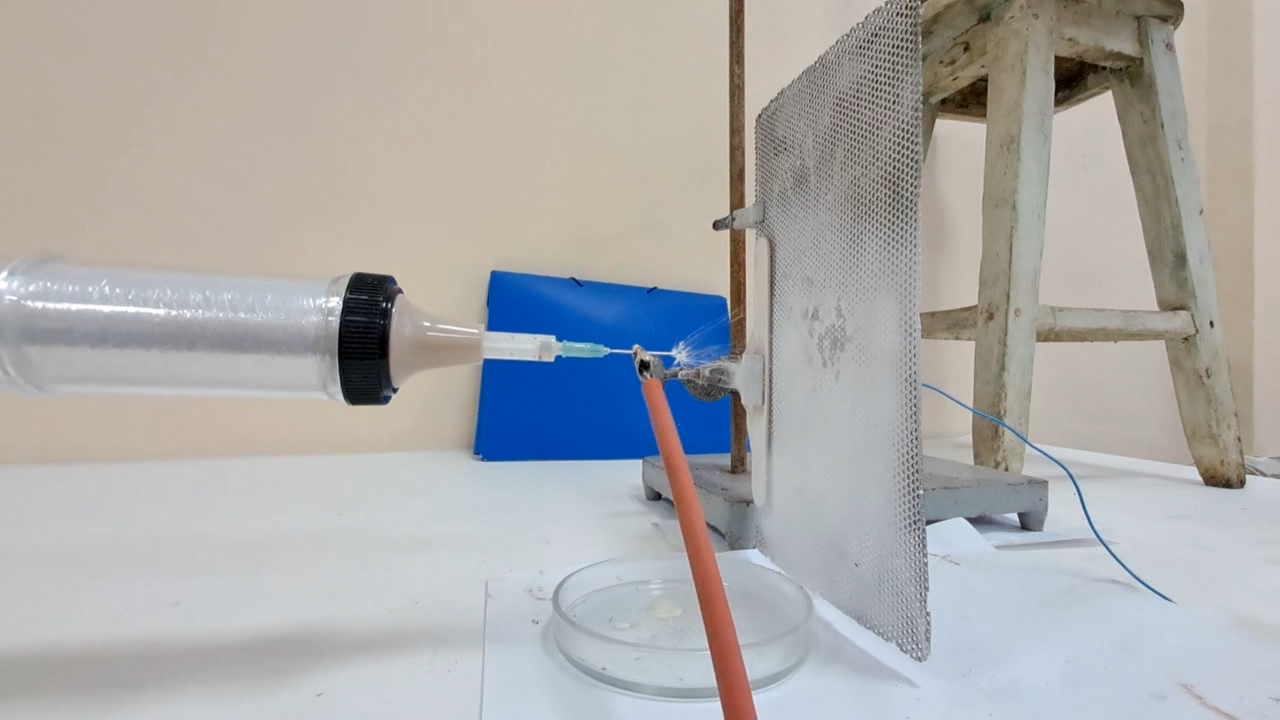

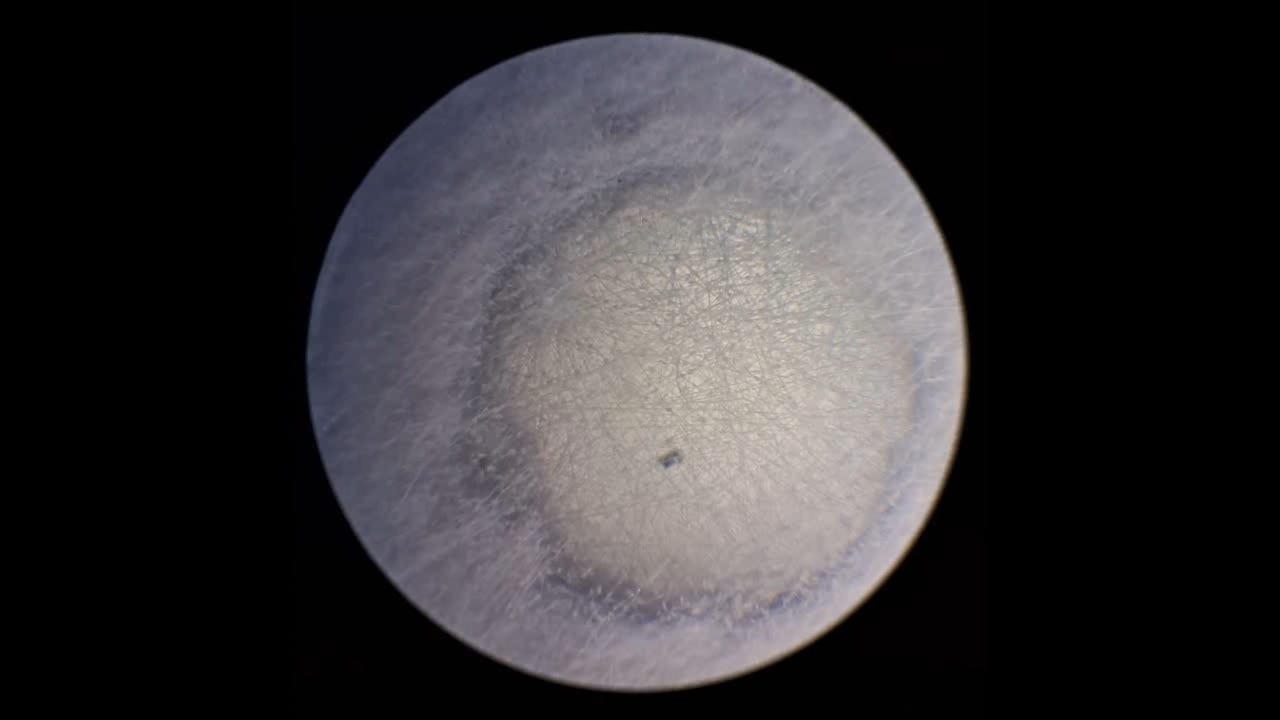

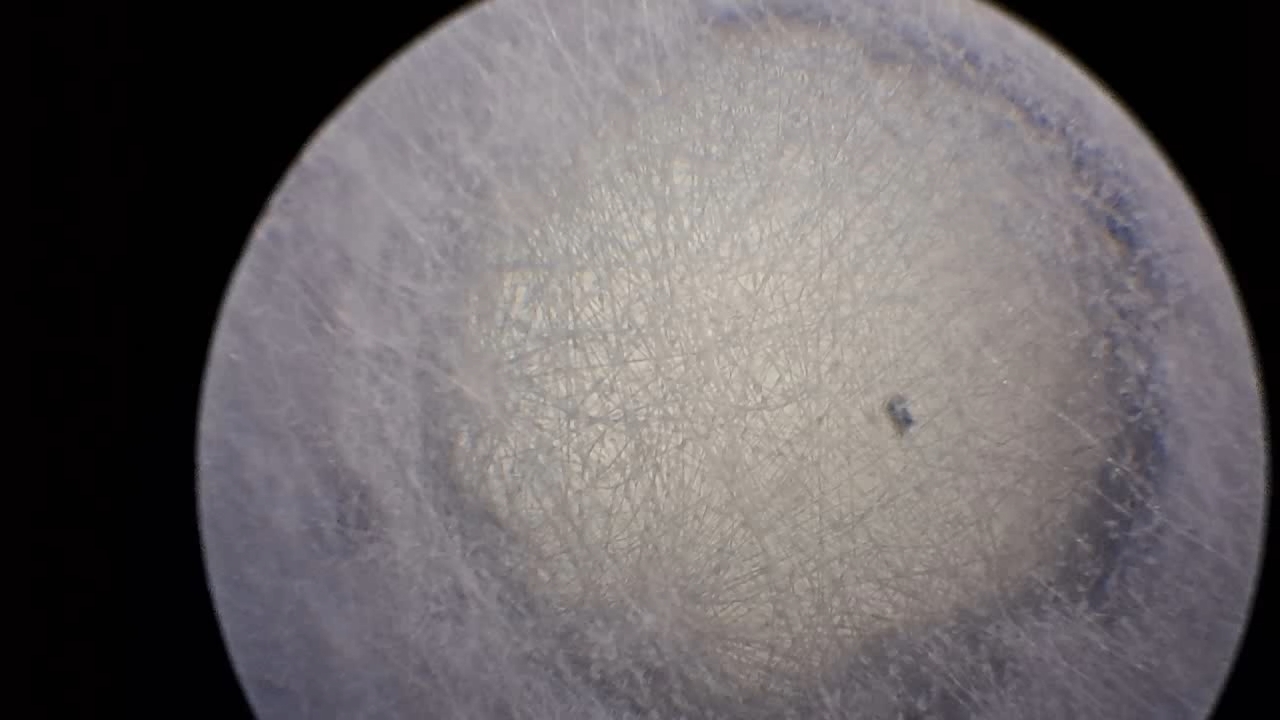

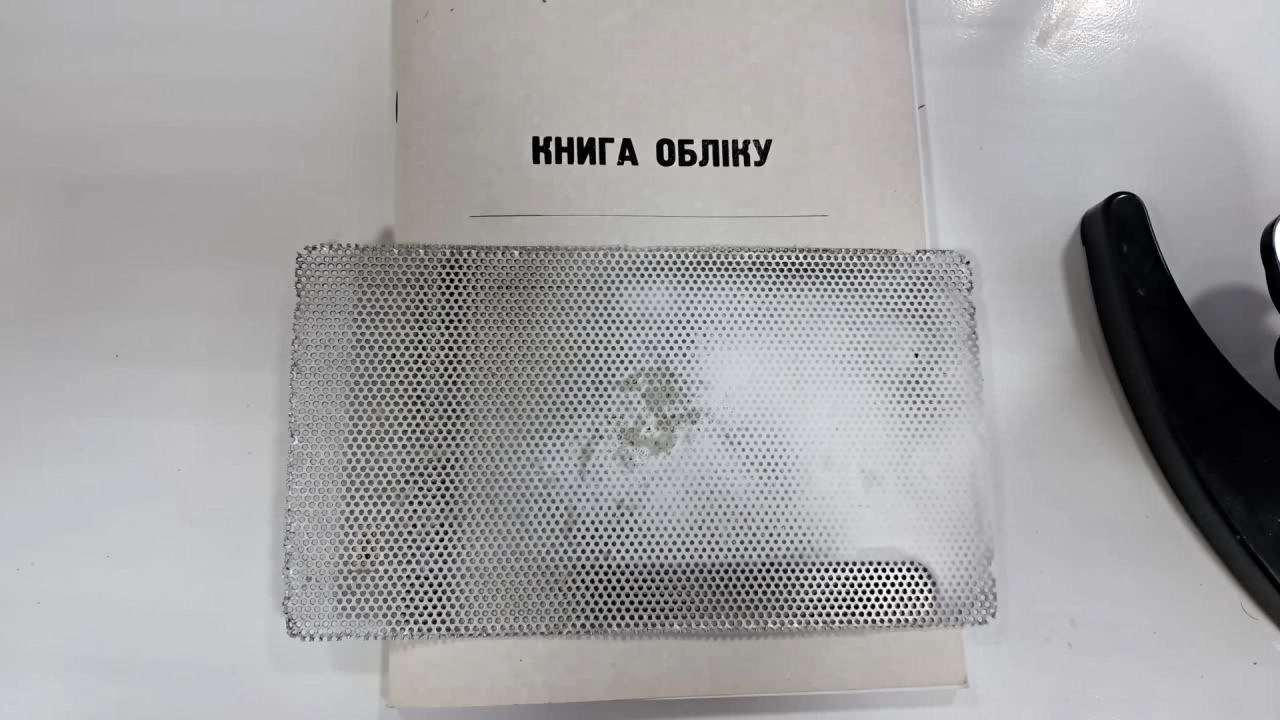

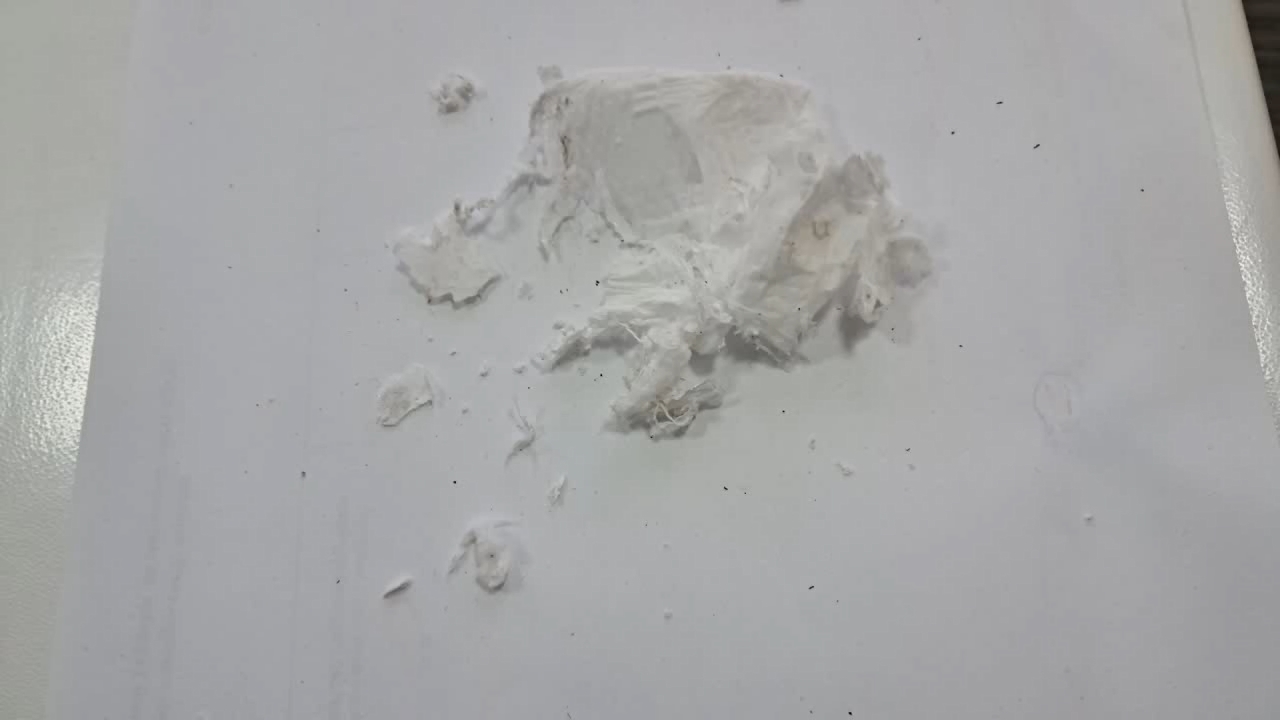

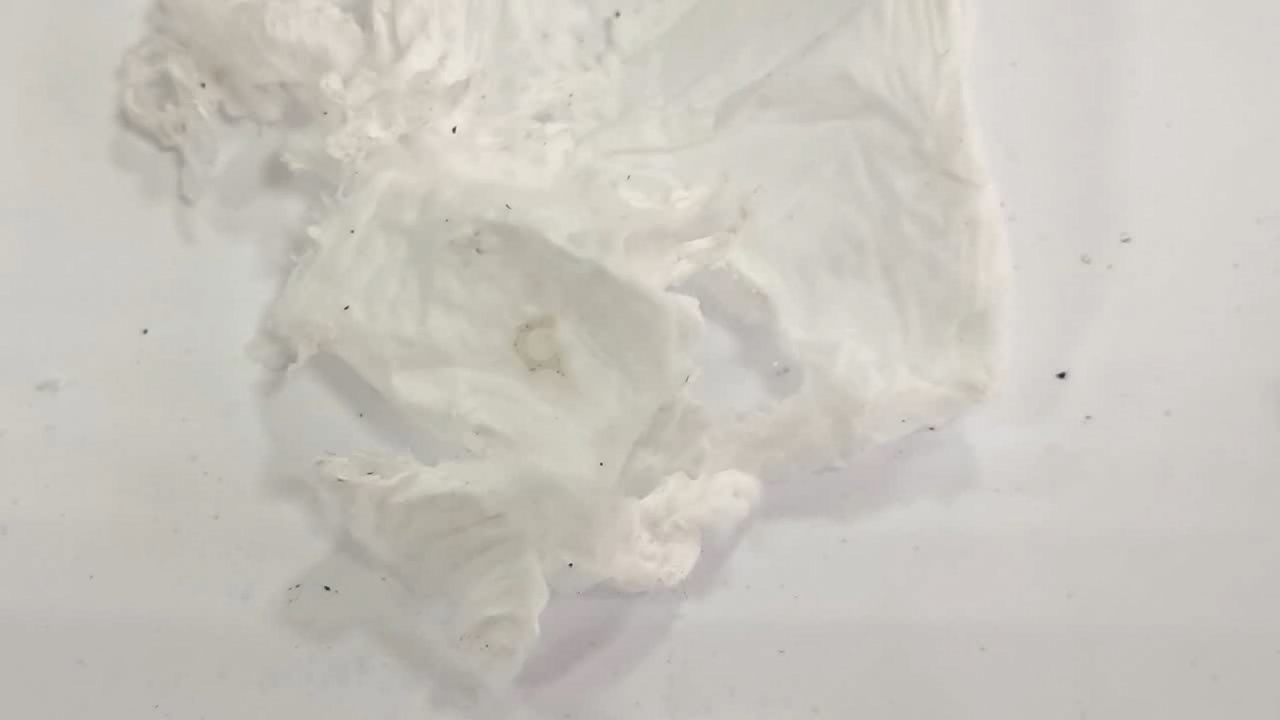

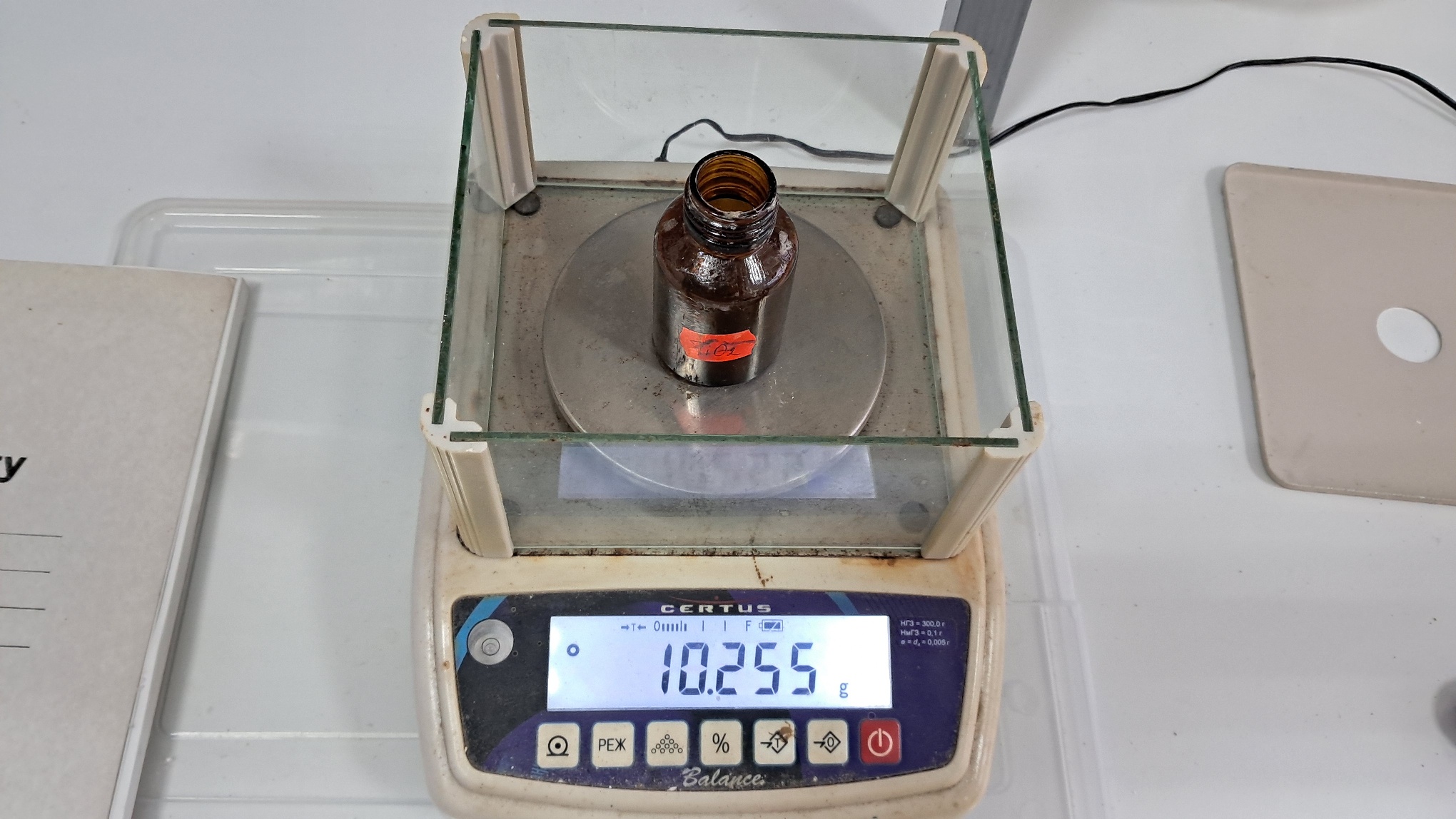

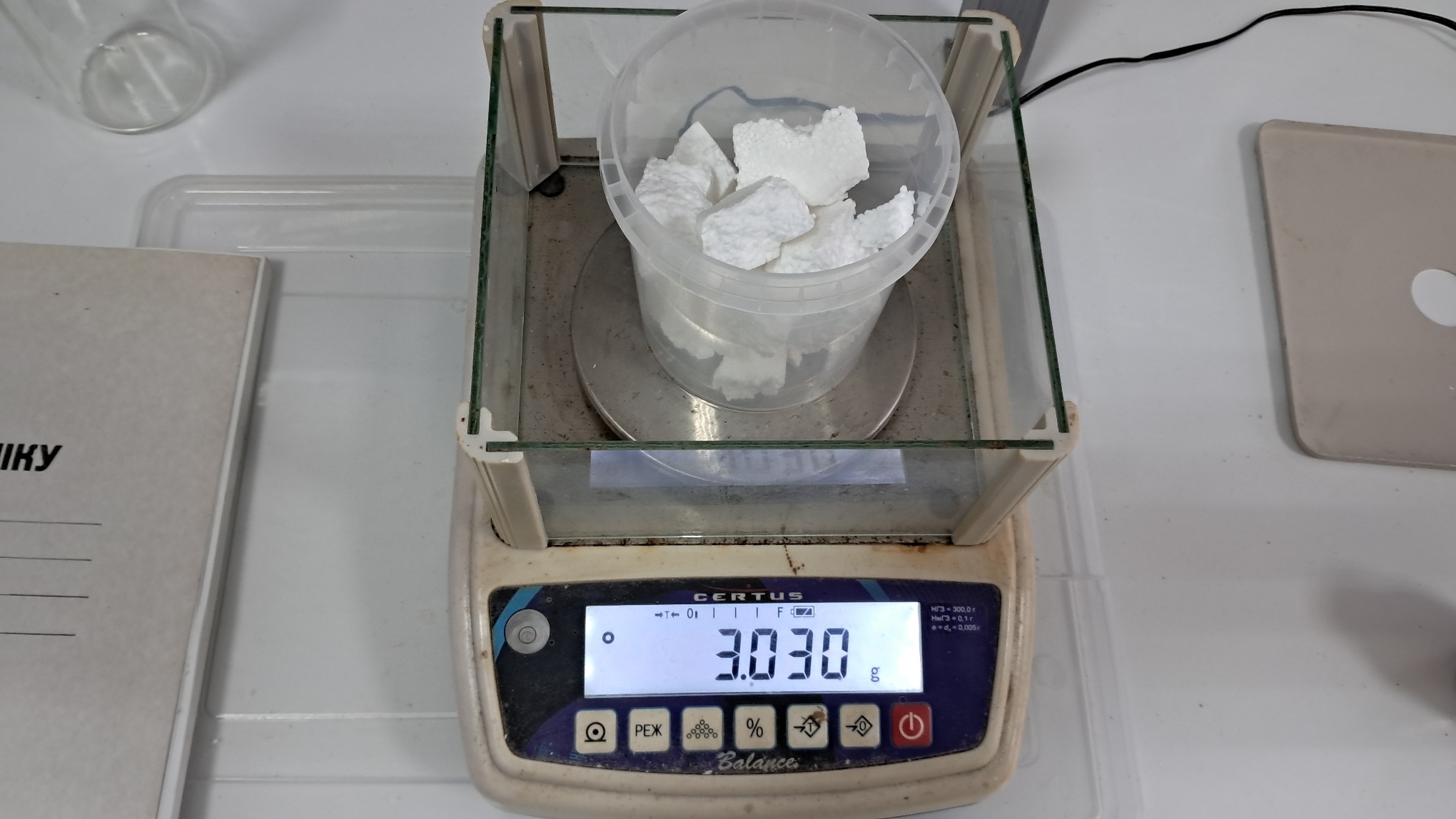

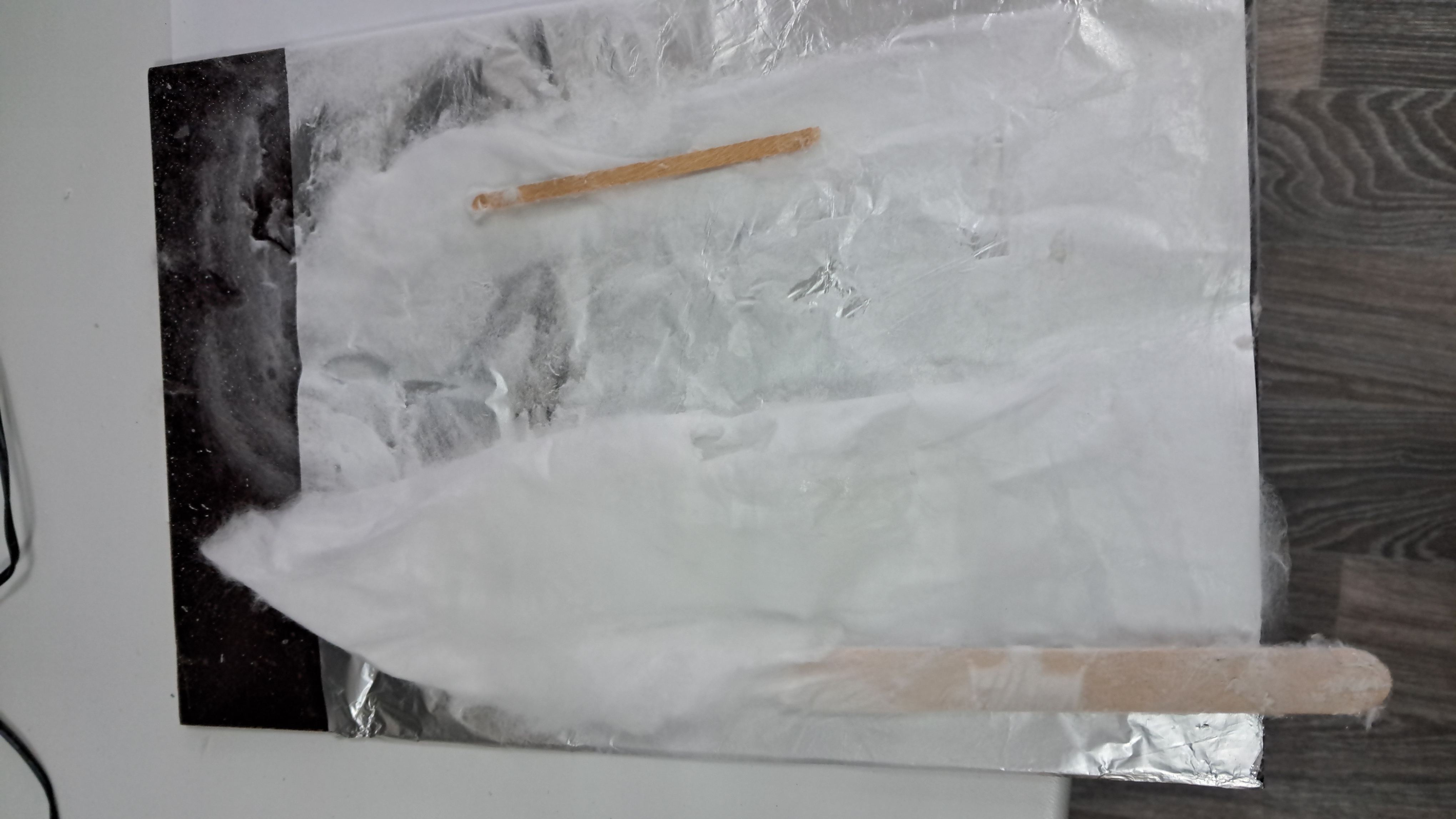

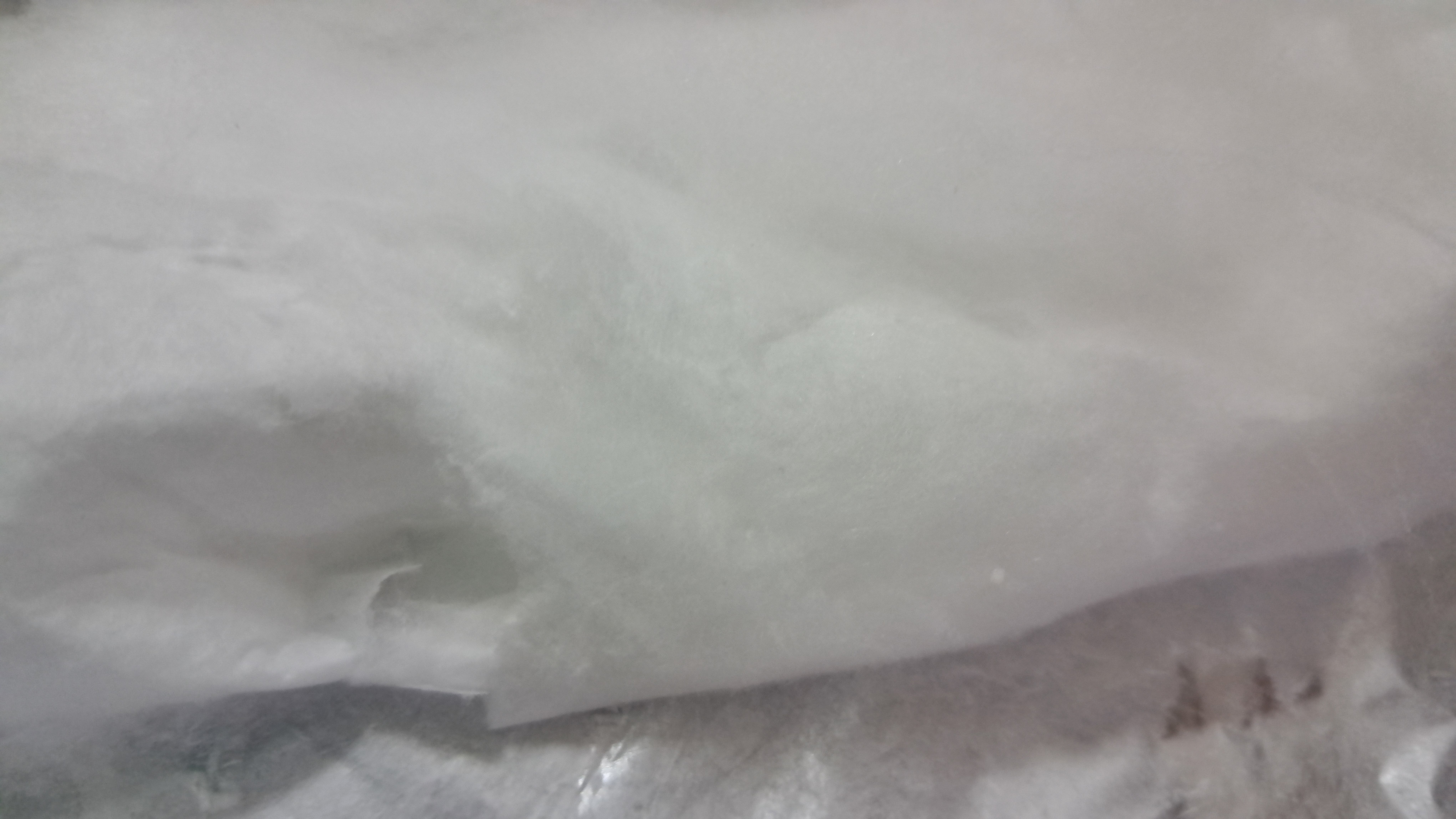

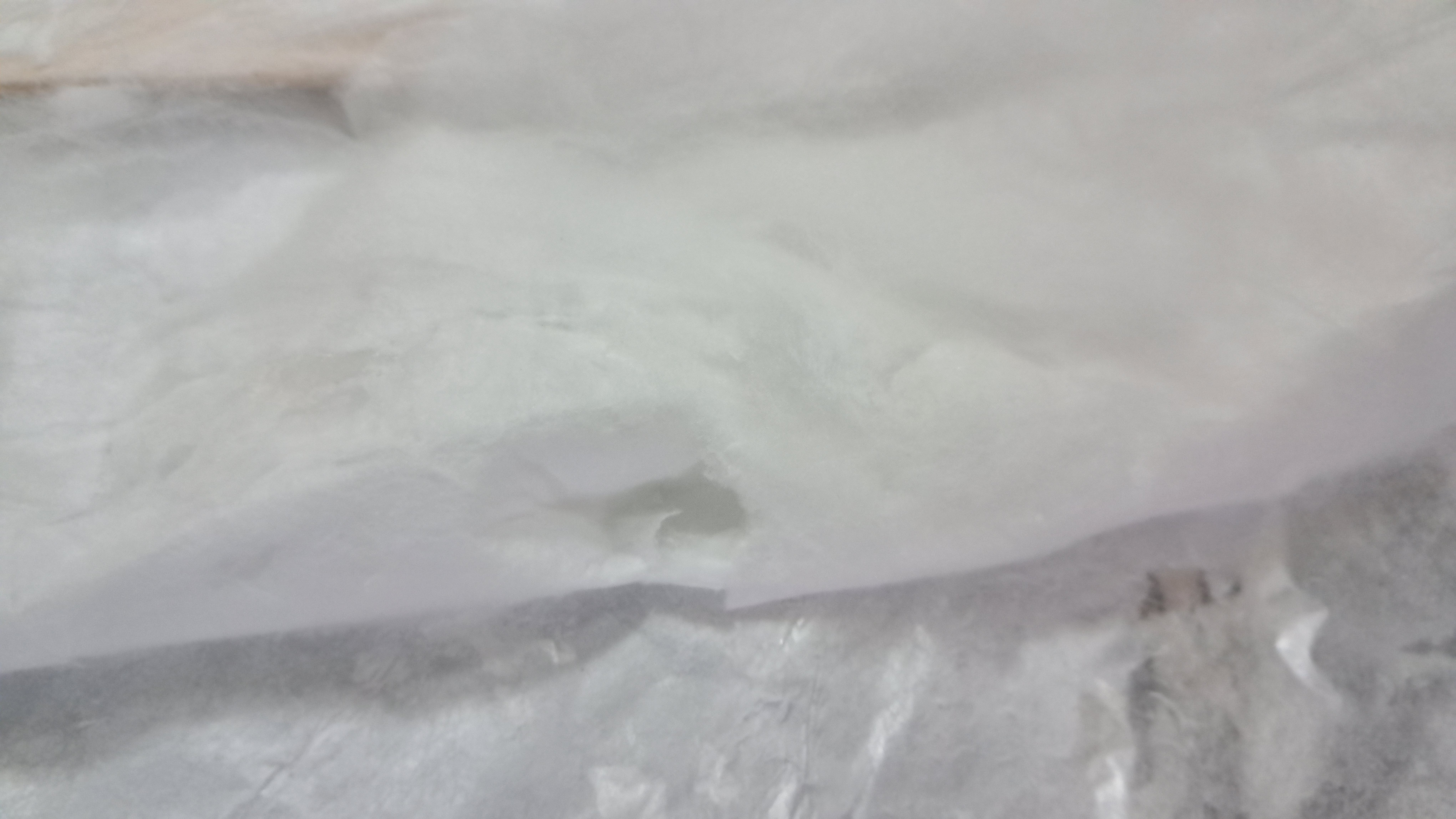

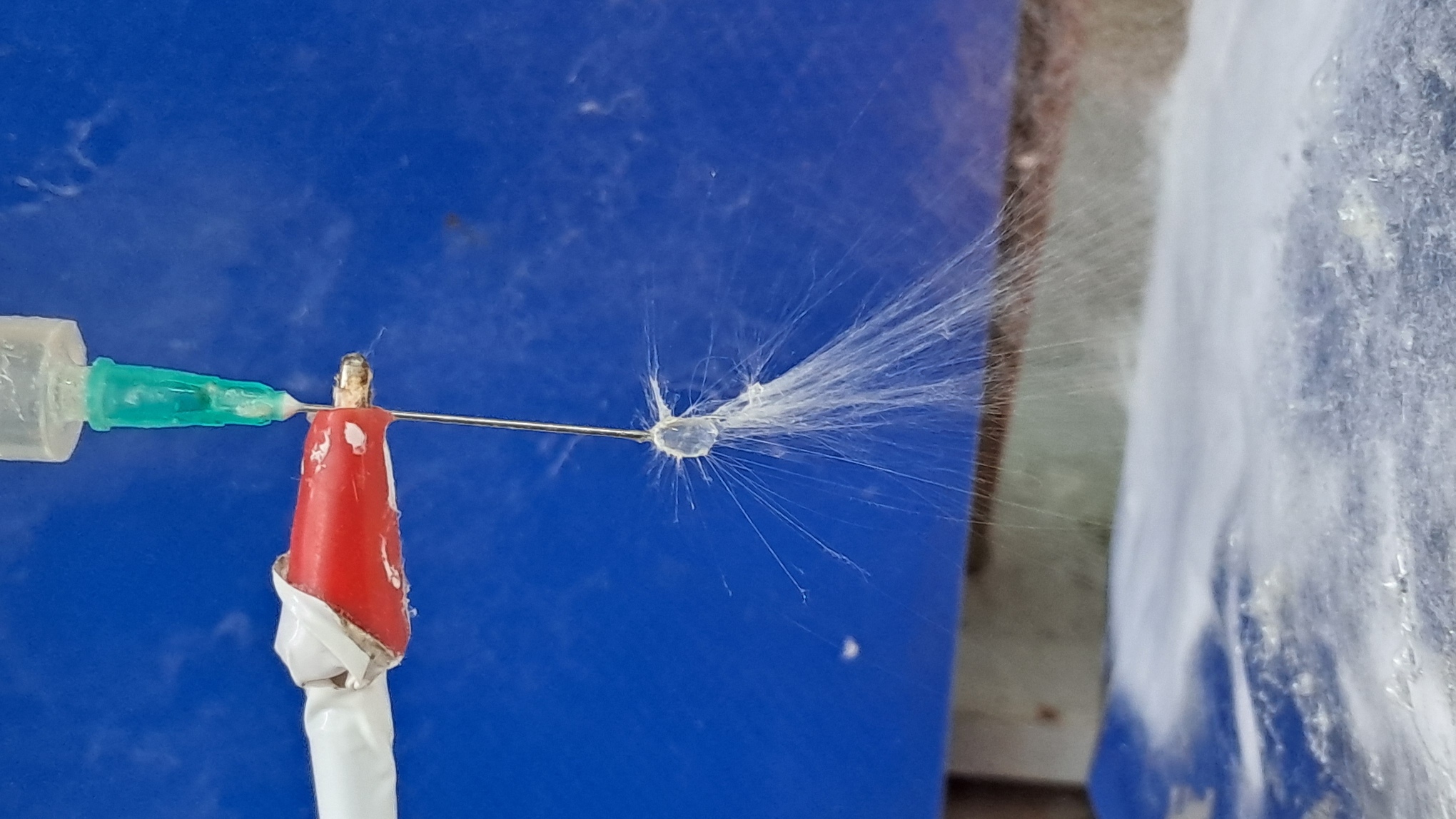

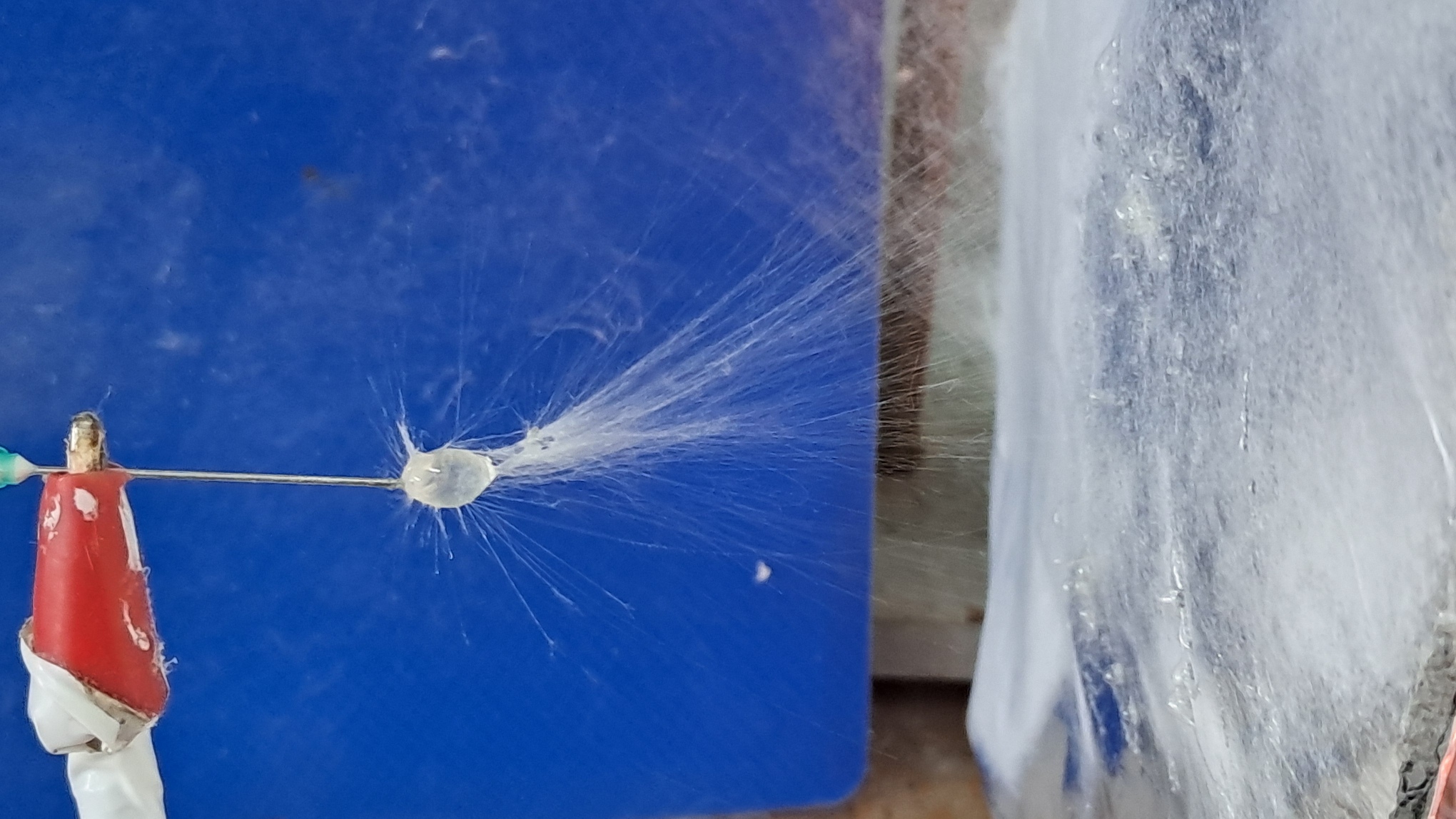

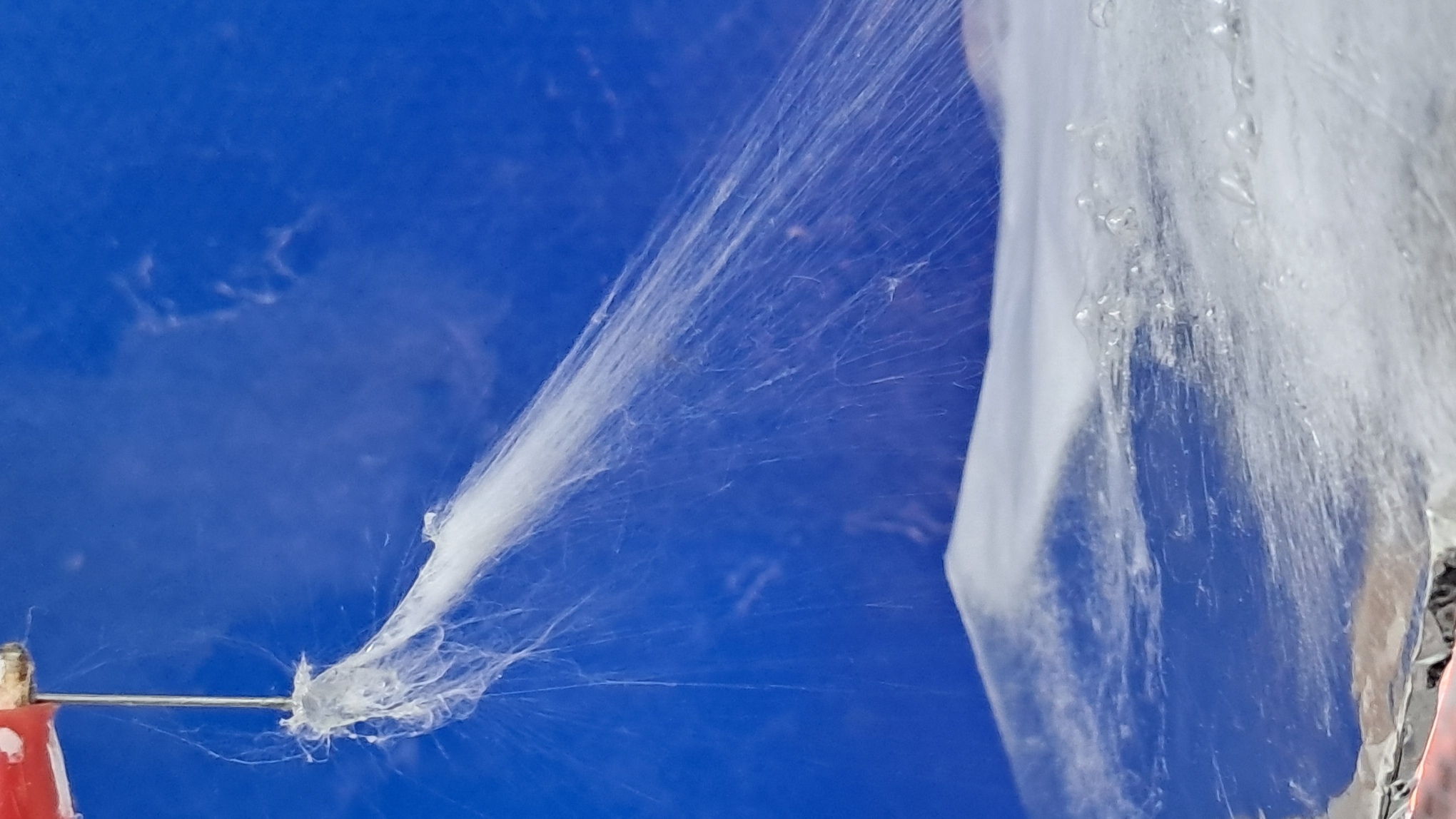

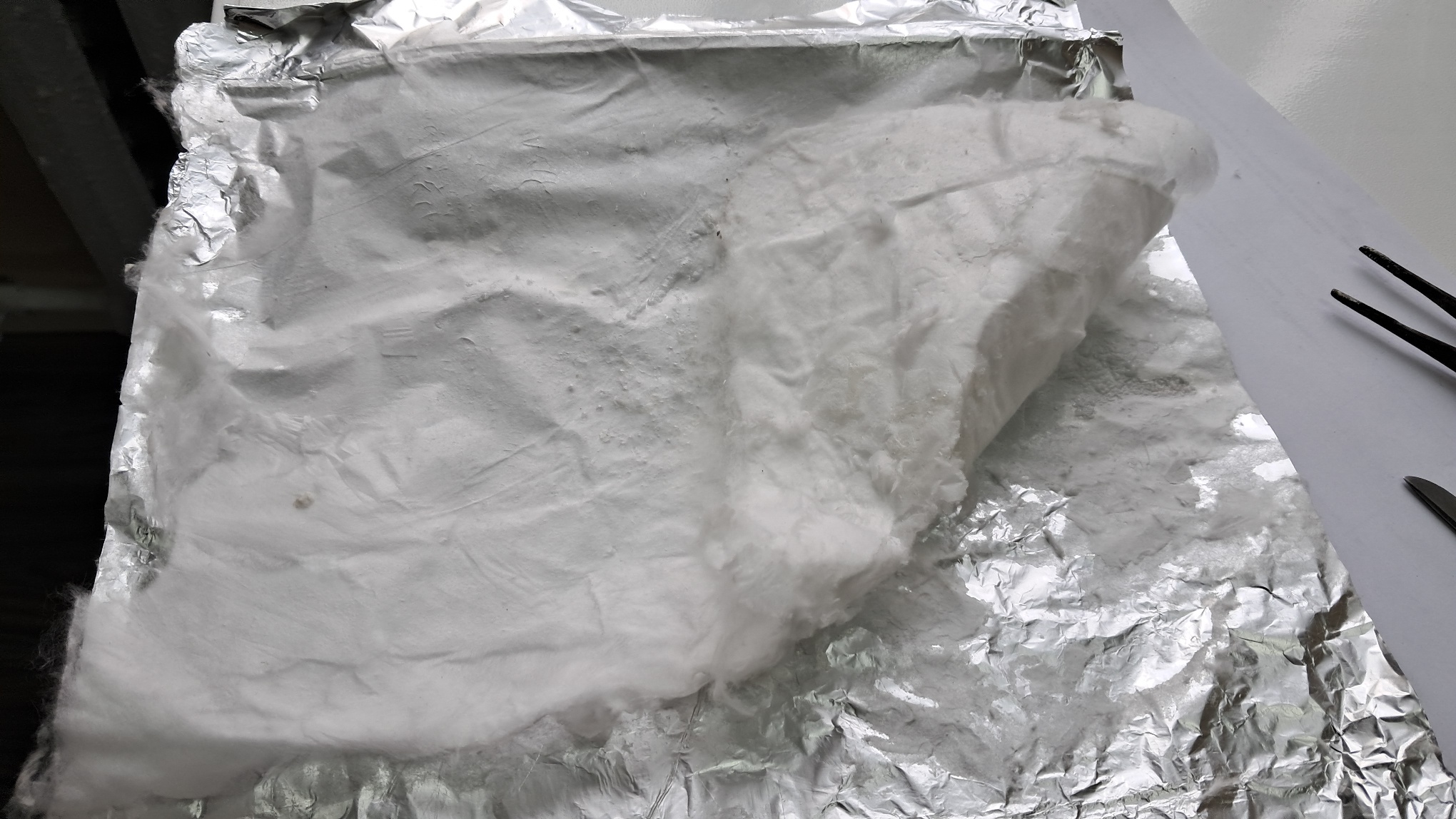

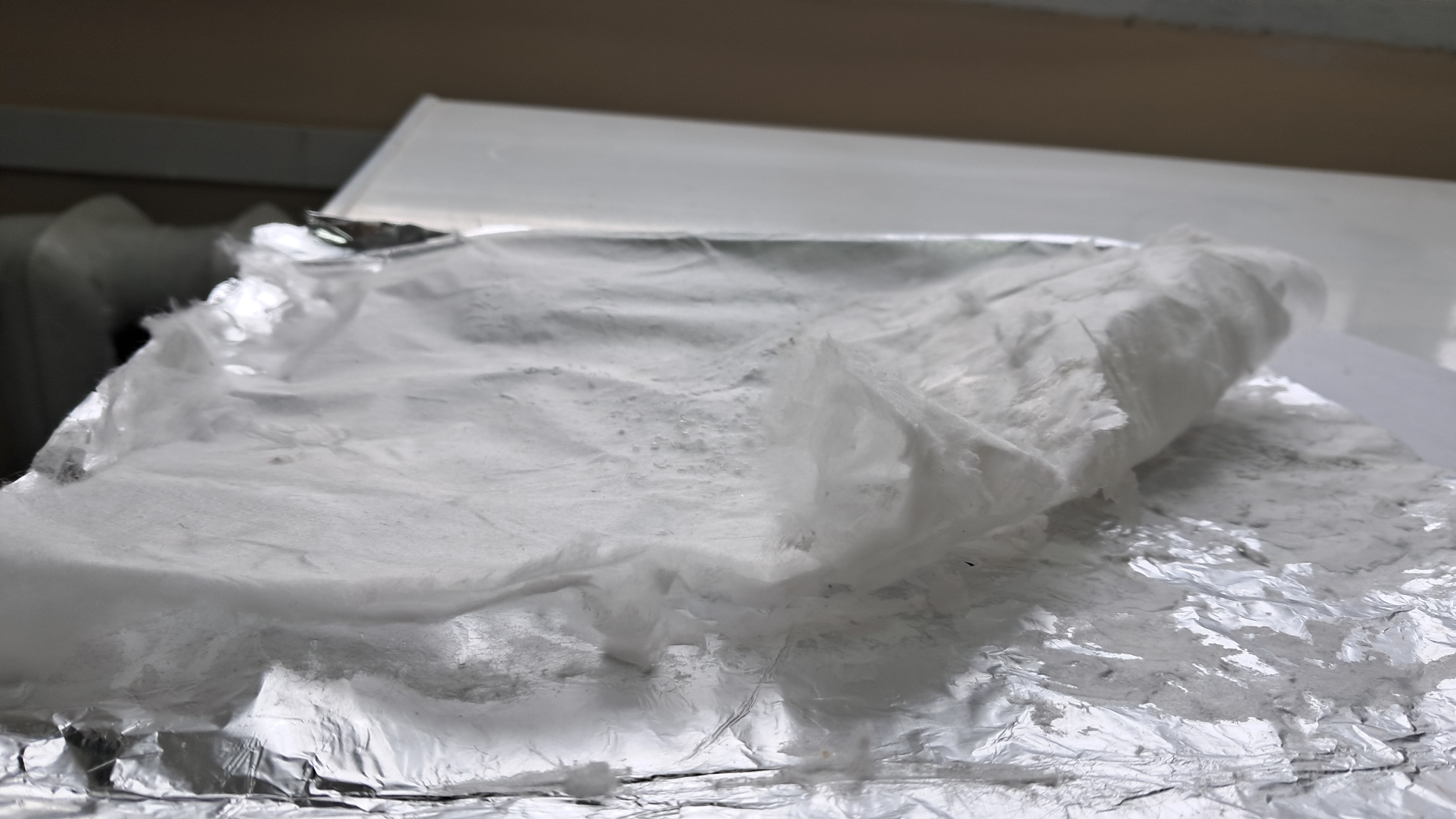

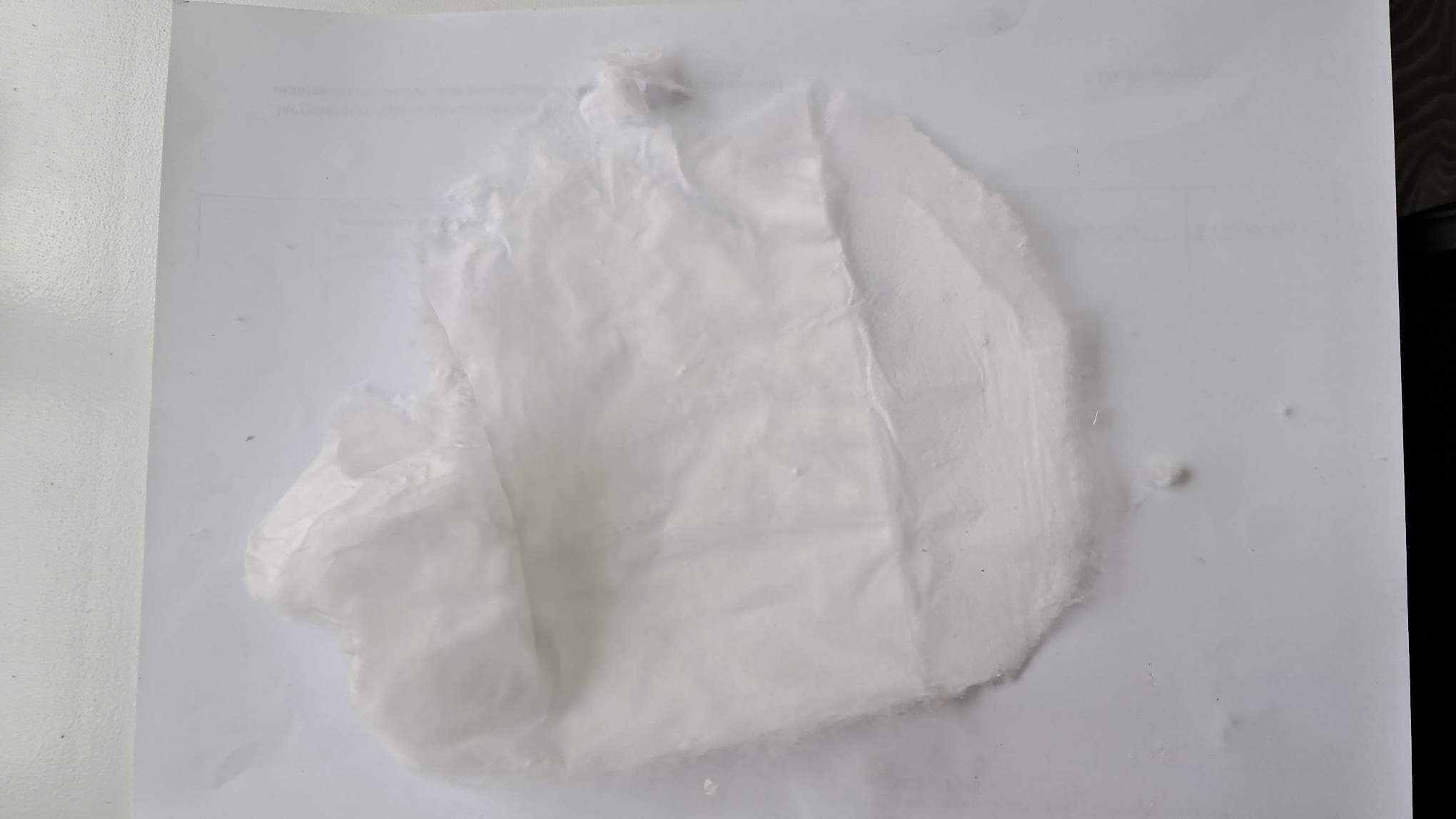

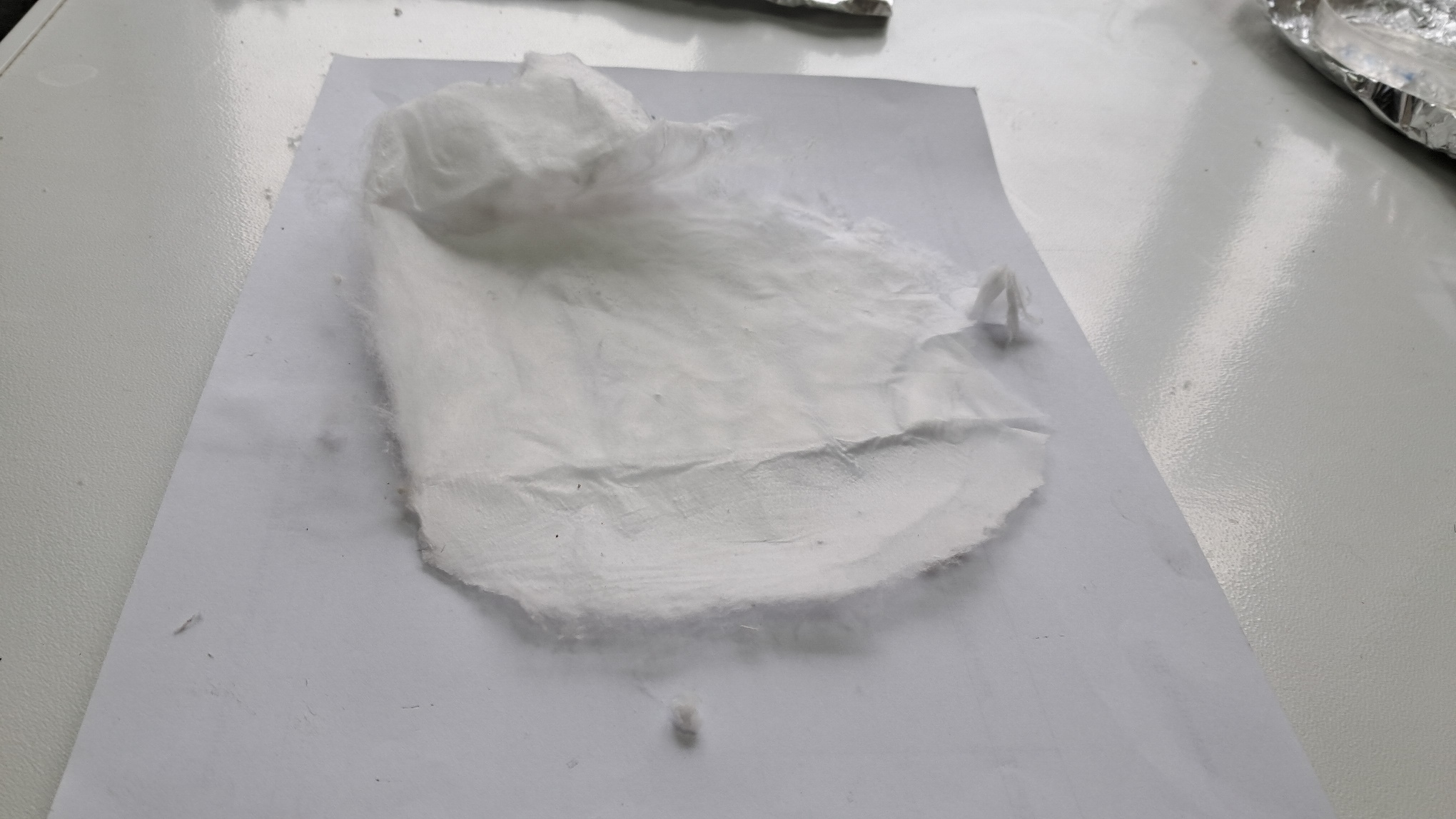

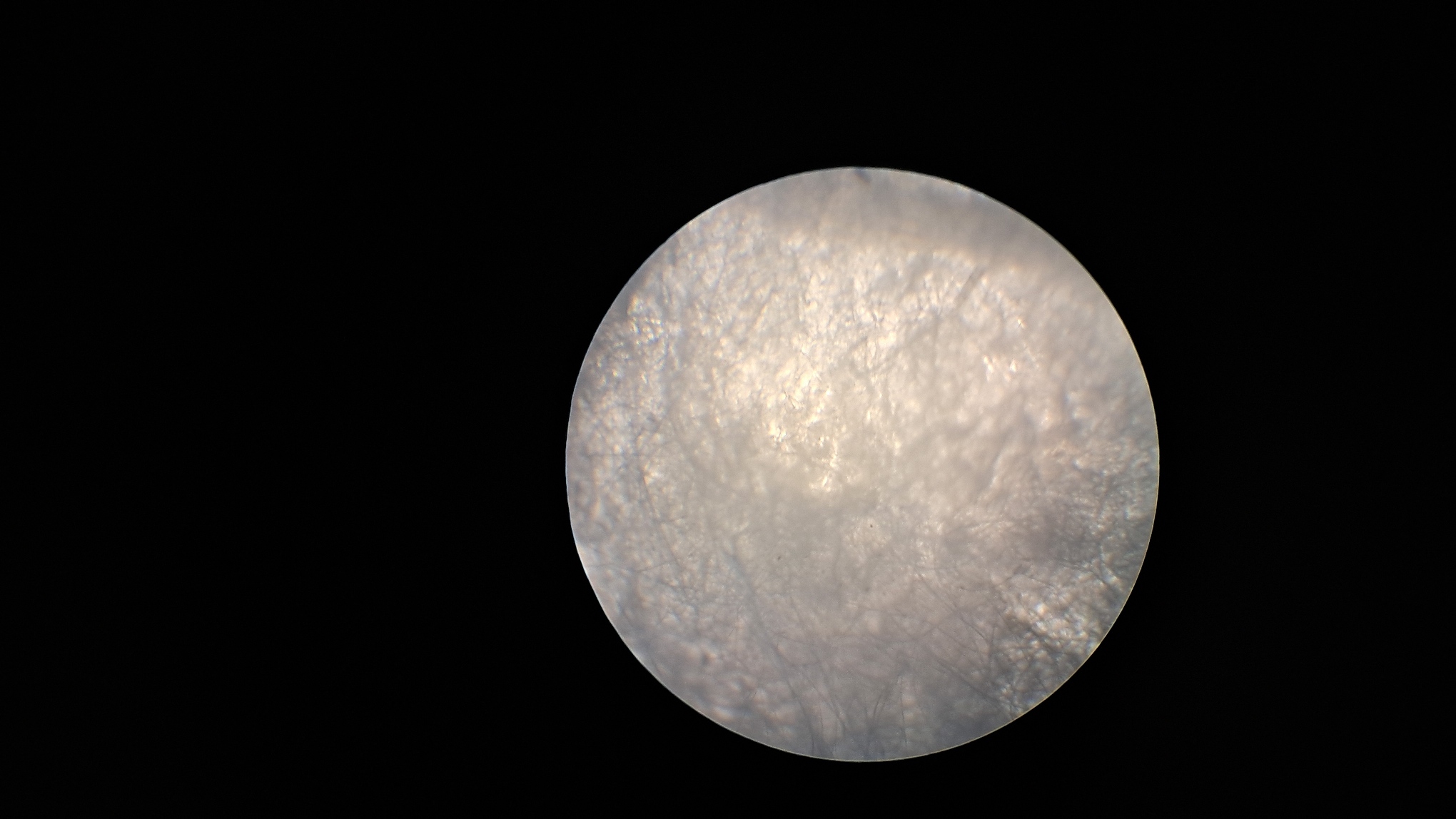

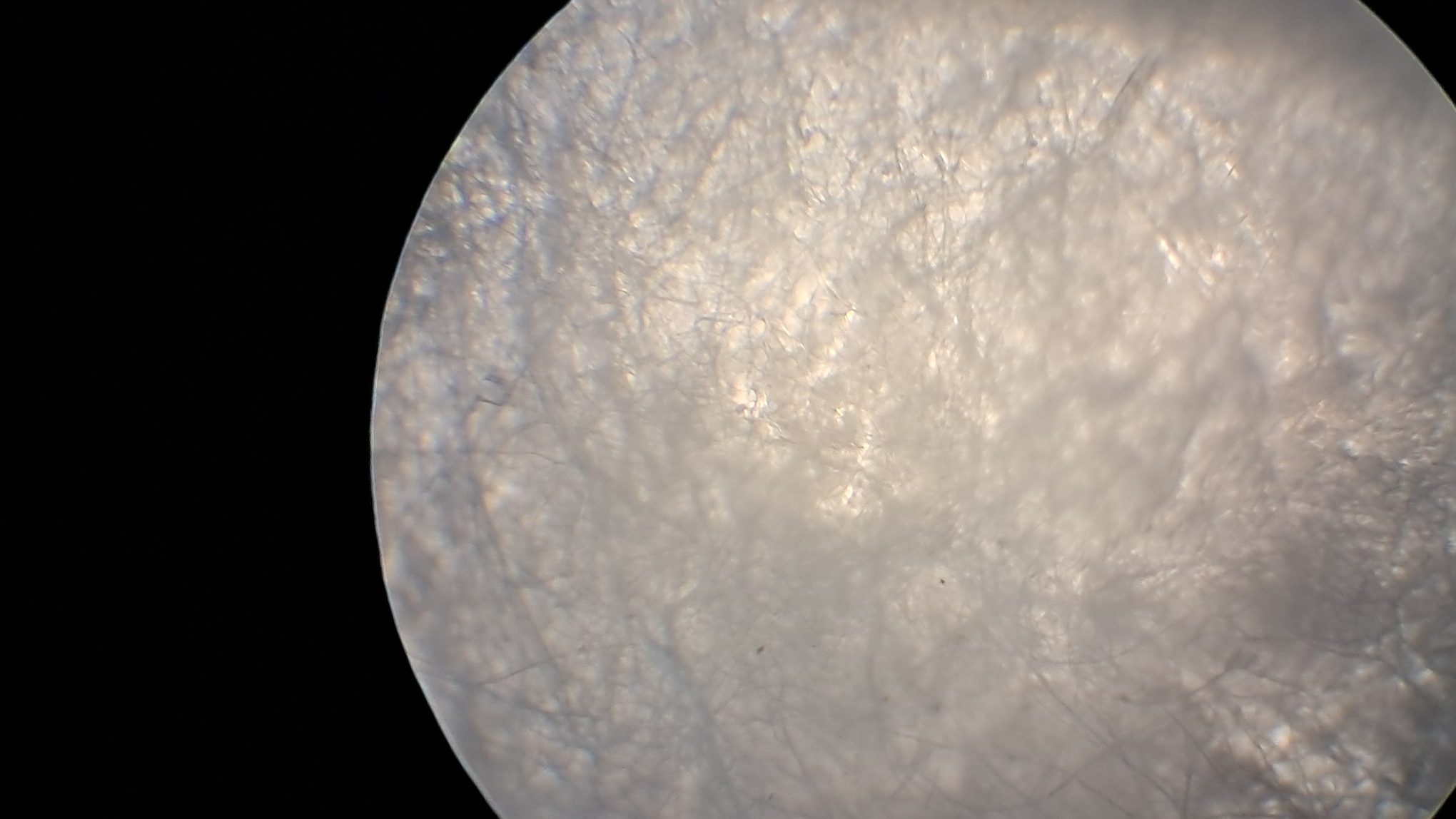

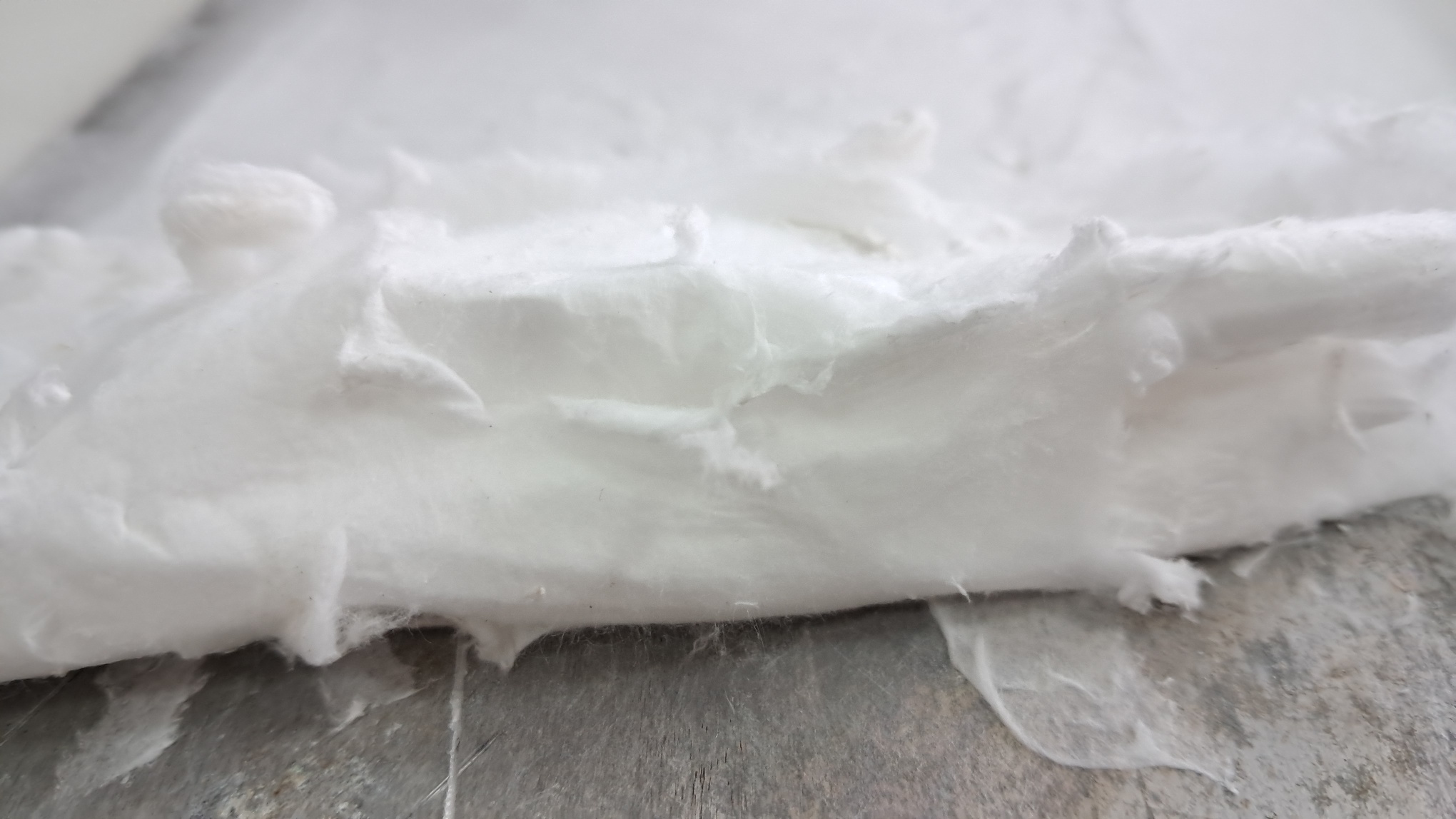

Электроспиннинг: раствор полистирола в суррогатном ацетоне (пробный эксперимент) - Часть 5 Among the possible reasons for the failure of electrospinning, I identified two: insufficient transformer voltage and the excessively high boiling point of the solvent, DMF. I couldn't replace the transformer in the short term, so I had to change the solvent. Besides DMF, PVDF polymer dissolves well in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) but poorly in tetrahydrofuran (THF). DMSO's boiling point (189°C) is even higher than DMF's. Therefore, both DMSO and THF were out of the question. This means I need to change not only the solvent but also the polymer. I had a solution of expanded polystyrene (polystyrene foam) in a substitute acetone, sold under the name "Acetone+." I used this solution as a homemade glue. The sale and use of pure acetone in our country is subject to strict restrictions, which are practically equivalent to a ban on this solvent. Besides acetone, other substances important for science and industry, such as sulfuric acid and hydrochloric acid, are also strictly restricted. The restrictions were introduced under the guise of combating illegal drug production. However, the real reason for the restrictions is different: the more bans there are in the country, the more extortion government officials can engage in. Those who cannot or do not want to pay corrupt officials are forced to use various substitutes for important and necessary substances. In particular, "Acetone+" is an acetone substitute in which some of the acetone is replaced with other solvents to avoid the restrictions. Naturally, this substitution degrades the solvent's properties and increases its price compared to pure acetone. The manufacturer didn't specify the exact composition of the "Acetone+" solvent, listing only a few of its components: acetone, methyl acetate, ethyl acetate, propyl acetate, and glycol ethers. For previous experiments, I needed glue, so I dissolved expanded polystyrene in the surrogate of acetone. I didn't weigh the components; I simply added the polystyrene to the "Acetone+" until the desired viscosity was reached. The expanded polystyrene dissolved quickly and completely. I decided to use this ready-made solution to produce polystyrene fibers, similar to how I had attempted to produce PVDF fibers. Unfortunately, the exact composition of the solvent was unknown and likely varied significantly from batch to batch. I also strongly suspected that the manufacturer had intentionally provided an inaccurate list of components. Specifically, this solvent is only slightly soluble in aqueous sodium hydroxide. However, almost all of the components listed by the manufacturer are soluble in aqueous sodium hydroxide - acetone, methyl acetate, ethyl acetate, and propyl acetate. Only glycol ethers can be insoluble in aqueous alkali. However, I decided that this solution would be suitable for trial experiments. If the results were positive, the surrogate could be replaced with chemically pure acetone, a small amount of which a colleague had left over. I drew the polystyrene solution into a syringe, secured it in the setup, and connected the high-voltage electrode. I turned on the solution supply and turned on the high voltage. A drop of the polystyrene solution formed at the tip of the syringe, and the needle was producing a familiar hissing and whistling sound. Transparent and colorless threads then emerged from the drop and were attracted to the collector, forming numerous branches. This was my first encounter with the "electrospinning" dendrites I mentioned in the previous part of the article. I didn't observe any "fog cone" composed of microscopic fibers or any similar structure. The droplet at the tip of the needle extended toward the opposite electrode, and fibers "shot" out from various points. I attempted to collect these fibers using a wooden frame with a plastic mesh inside. I moved the frame in translational and rotational motions near the collector electrode, recalling what the colleague had done in our first experiments. He hadn't succeeded then - the plastic mesh remained unchanged. But now the mesh was covered in a "web" - microscopic polystyrene fibers! This was the first positive result. The fibers, however, formed with difficulty. The polystyrene solution was too viscous, but I didn't know that at the time - I had nothing to compare it to. So I positioned the needle closer to the collector. The result was a corona discharge, followed by a loud pop and a spark (an electrical breakdown of the gap between the electrodes). Neither the computer monitor used as the high-voltage source nor I was injured, but I jerked my hand away in panic, breaking the wooden frame. For some time, I continued to coat the mesh inside the frame with fibers, creating a dense web. The tip of the needle grew a beard of dendrites, which I occasionally removed with a long plastic stick. Later, I learned that the physicist colleague had done something similar in his previous experiments. Videos of electrospinning processes I found online showed no dendrite formation. This suggested I was conducting the experiment incorrectly, but there was no one to help me. I varied the distance between the needle and the collector and tried different flow rates. The dendrites didn't disappear. However, the collector became coated with a white material. It could be fibers or dried aerosol droplets. The former would have indicated a positive result, and the latter would mean a negative one. The colleague came in. Seeing the dendrites, he asked: "Polystyrene?" "Yes." "I see - you've made the excellent 'hedgehog'!" Of course, the goal wasn't to create a "hedgehog model," but to obtain microscopic polystyrene fibers, or better yet, nanofibers. To make the resulting coating easier to see under the microscope, I used an aluminum mesh as a collector instead of aluminum foil. The mesh became coated with a white material resembling cotton wool. After finishing the work, I removed the white material from the electrode with a scalpel. Under the microscope, it was clearly visible that the resulting material consisted of fine fibers. For comparison, I placed a piece of cotton wool under the microscope. It turned out that the fibers in the cotton wool had a significantly larger diameter than the electrospun fibers. The result was positive, but much work remained. Perhaps I should increase the concentration and viscosity of the polystyrene solution by dissolving additional expanded polystyrene in it? I did just that, obtaining a viscous solution that was difficult to squeeze out of the syringe needle. I connected high voltage to the needle and turned on the syringe pump. A drop appeared at the tip of the needle, gradually growing larger. However, it turned out that the electric field was unable to draw a Taylor cone from this solution. Neither fibers nor even an aerosol formed. The electrostatic force failed to overcome surface tension. My supply of polystyrene solution in "Acetone+" ran out. I prepared new solutions specifically for electrospinning. From this point on, I prepared the solutions by precisely weighing the required quantities of components. To begin, I prepared 18% and 20% polystyrene solutions in "Acetone+" solvent. |

Electrospinning: Solution of Polystyrene in Surrogate Acetone (Trial Experiment) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The corona discharge |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

Electrospinning: Solution of Polystyrene in Surrogate Acetone - Part 6

The fundamental problem had been solved: the electric field was able to draw thin fibers from the polystyrene solution, which were deposited on the opposite electrode, forming a layer of white nonwoven material. I could now produce electrospun polystyrene by varying the experimental conditions. However, numerous technical challenges still remained.

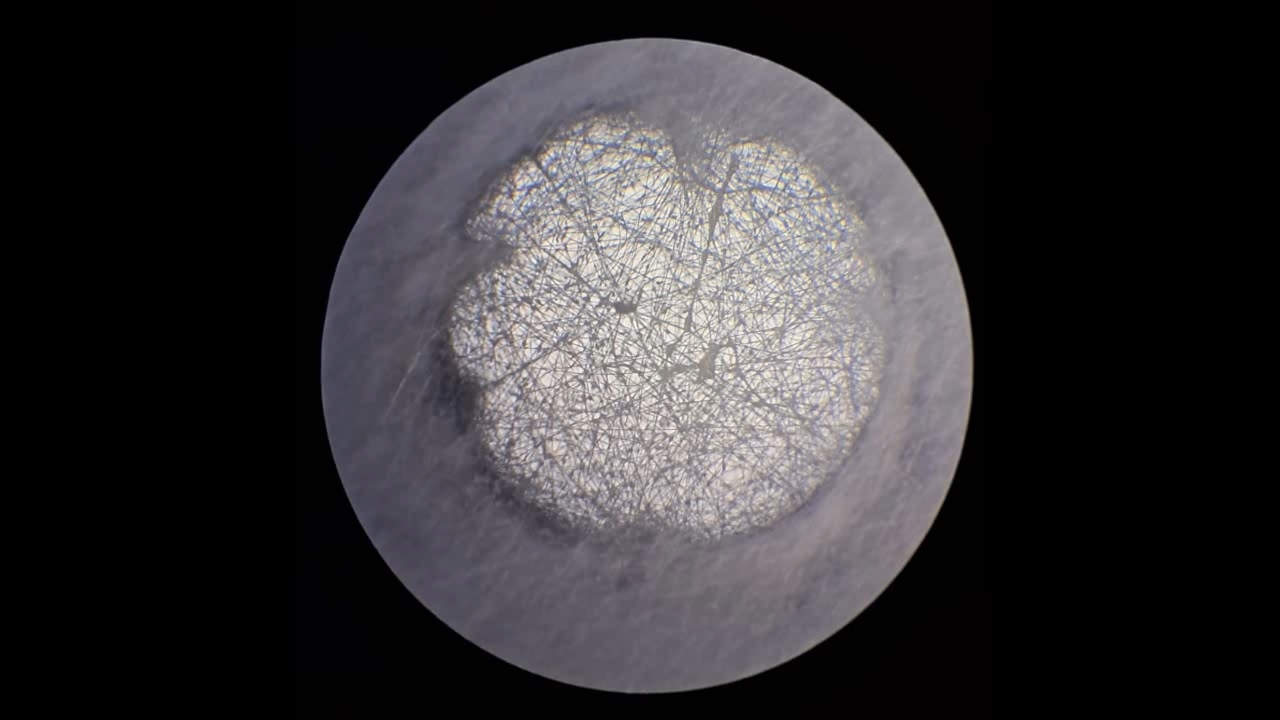

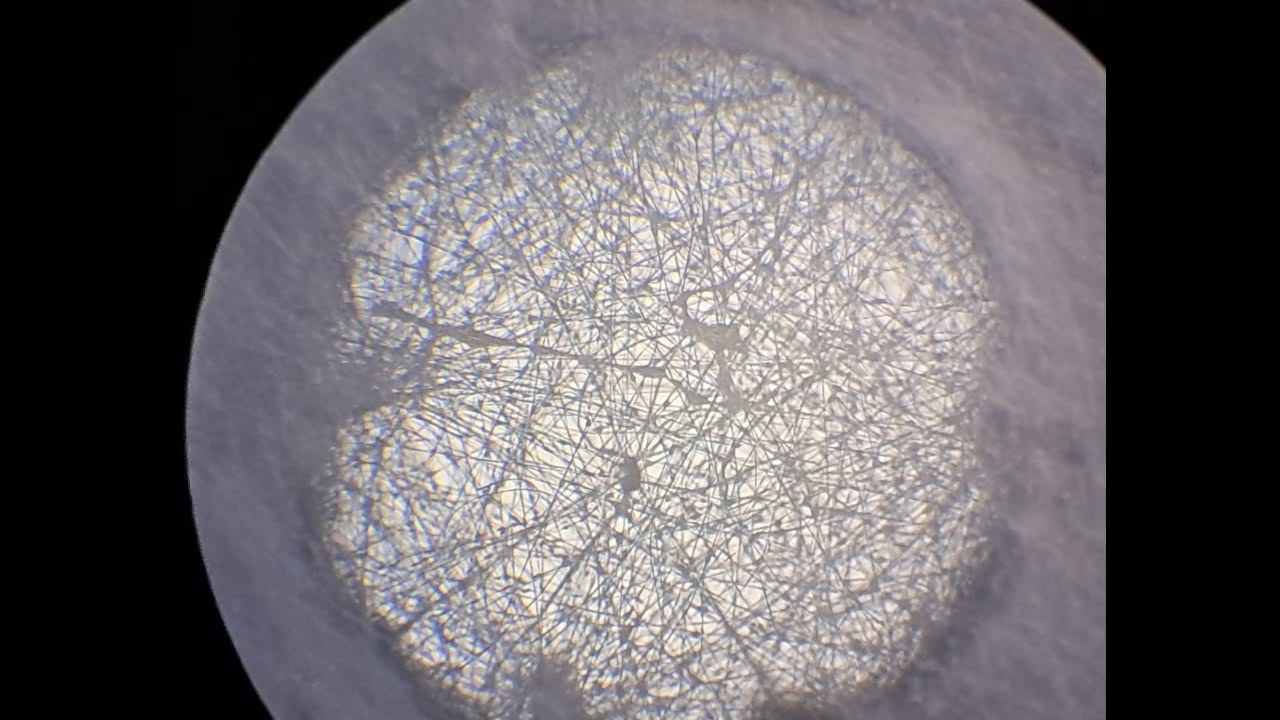

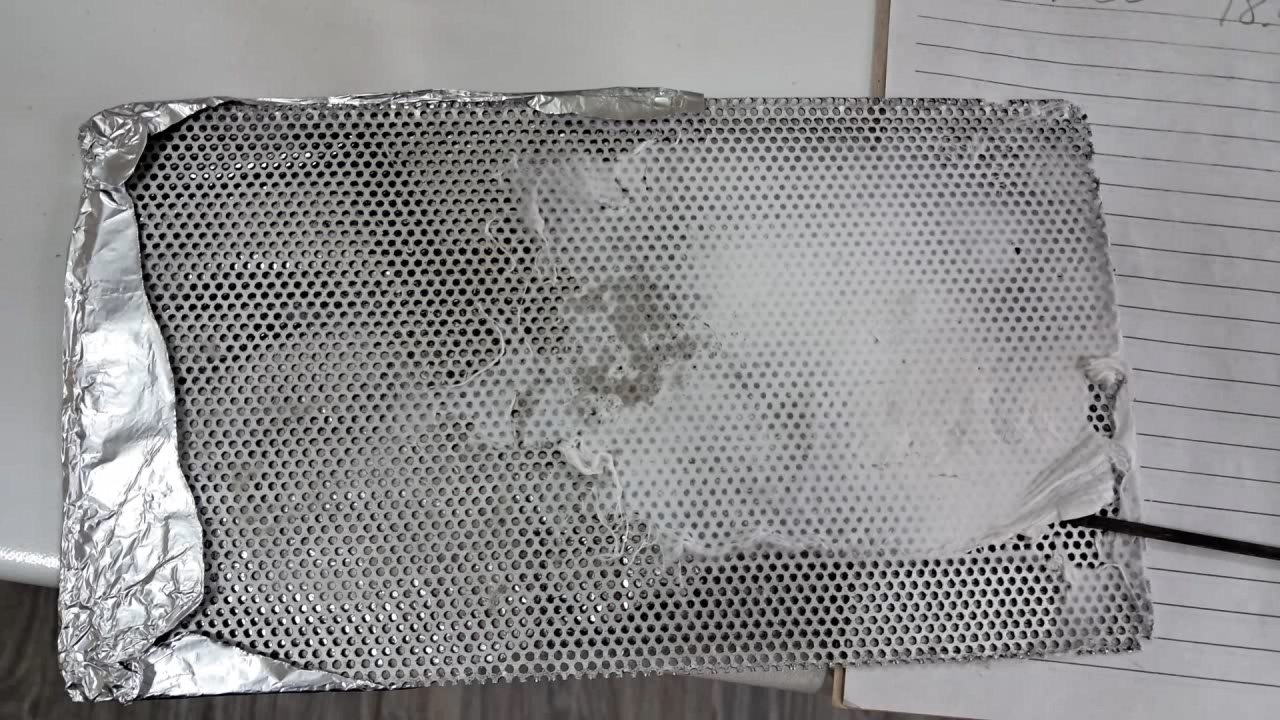

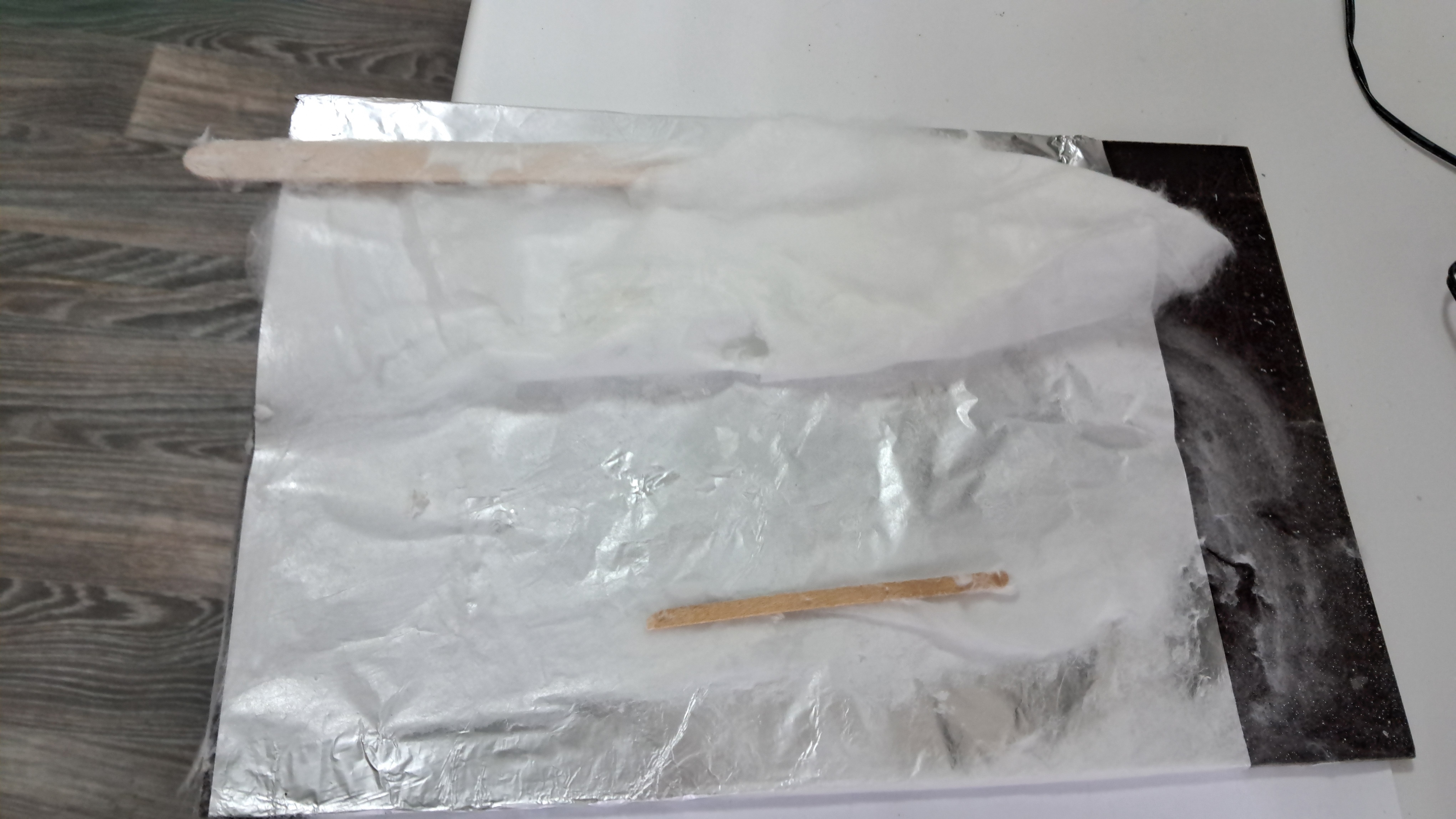

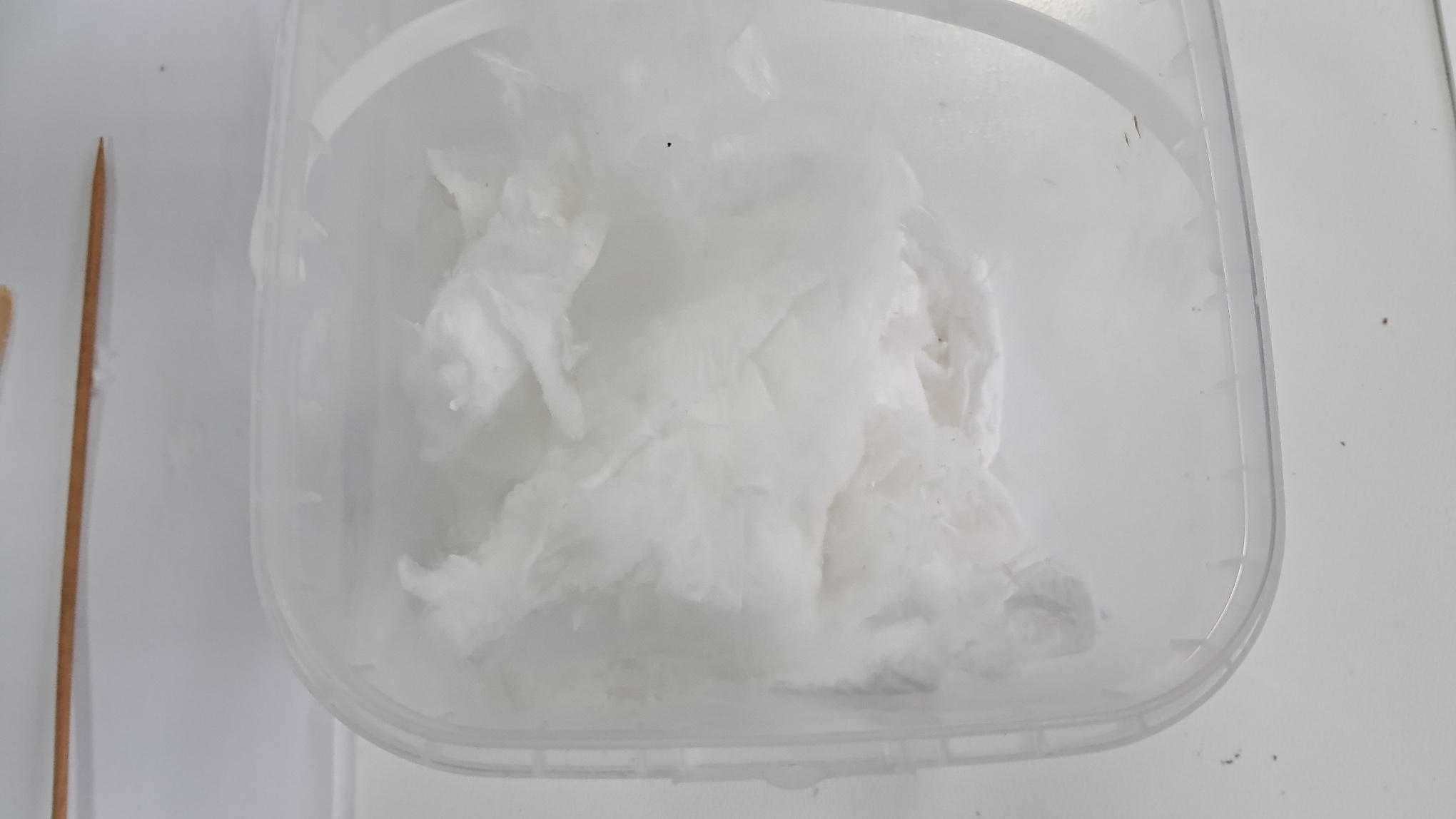

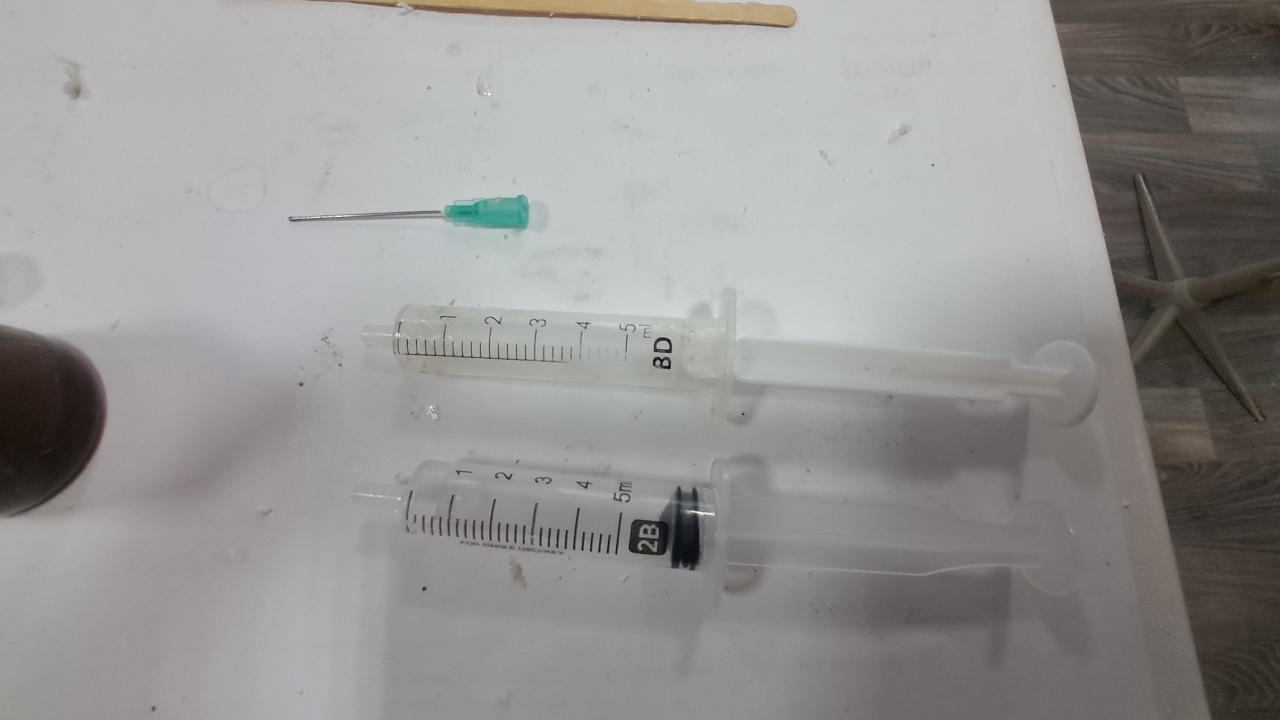

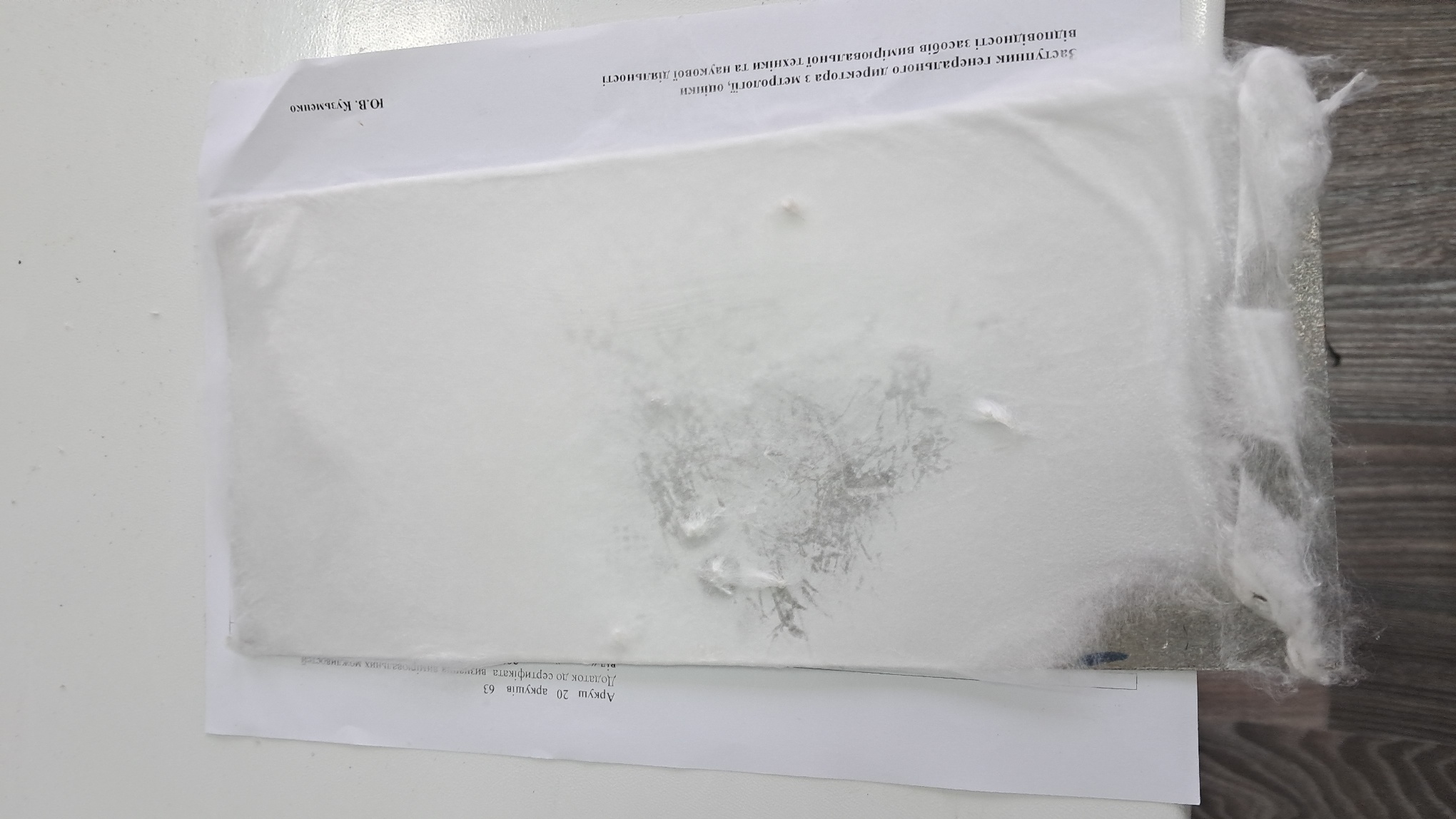

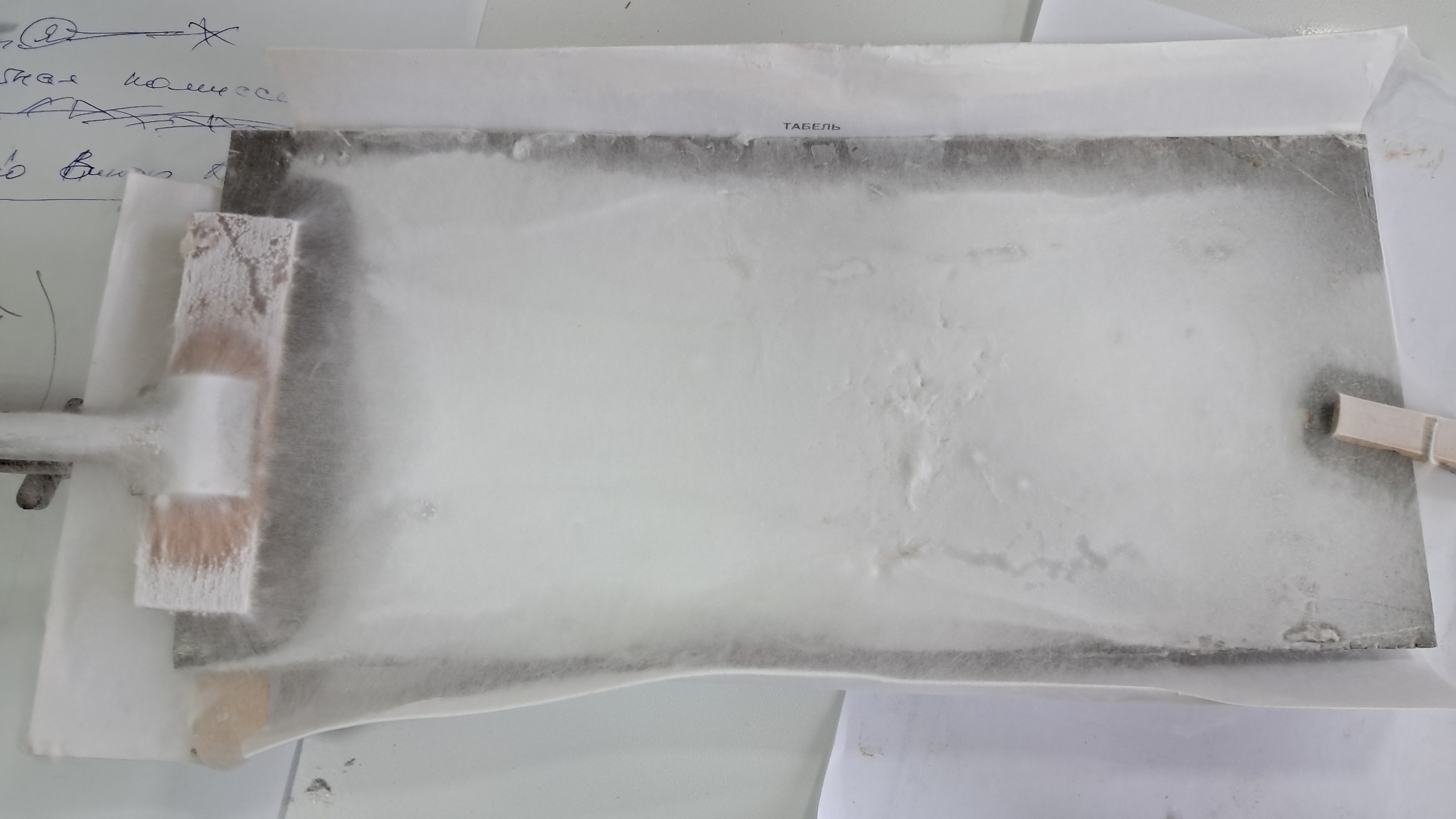

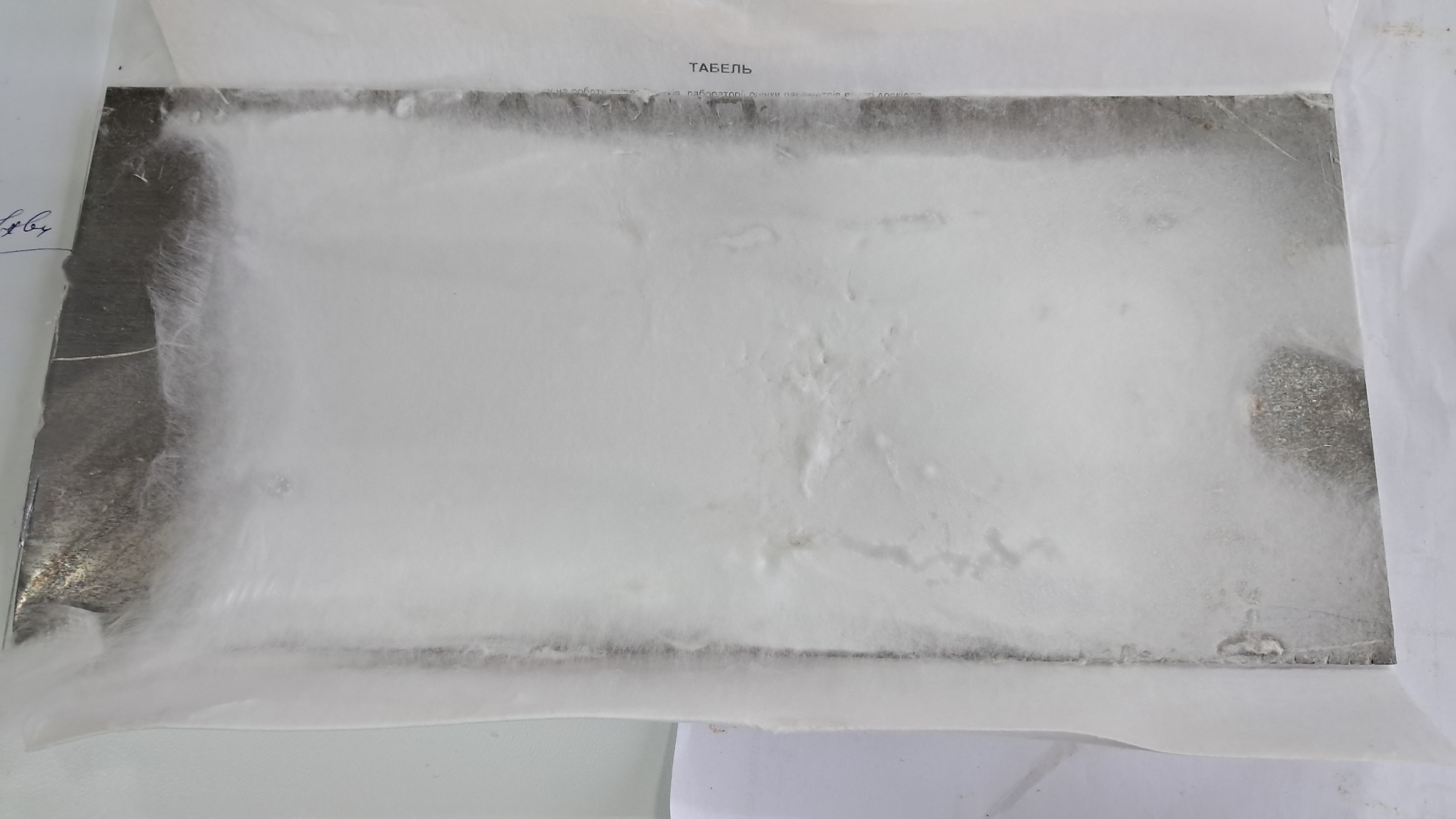

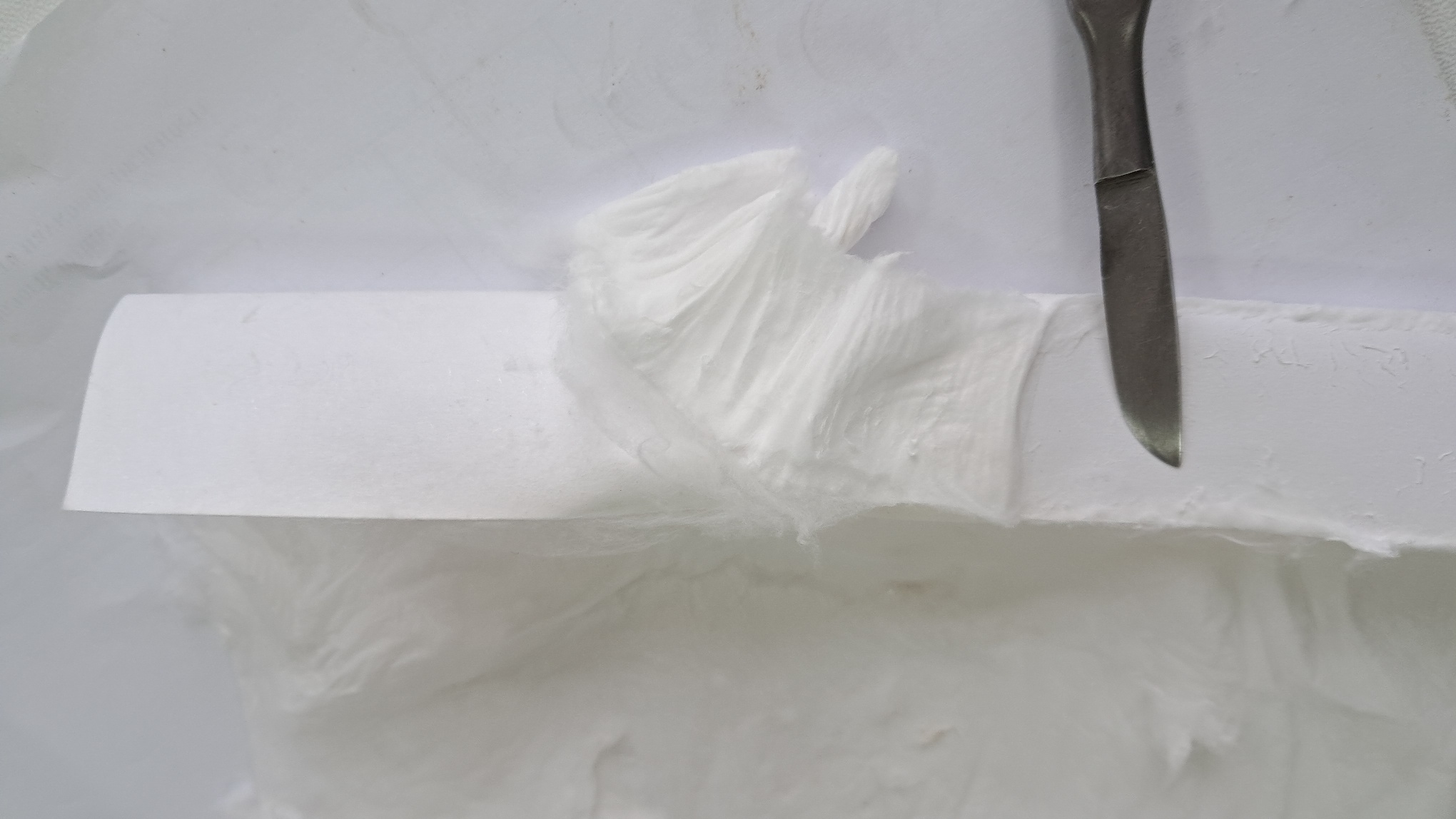

Электроспиннинг: раствор полистирола в суррогатном ацетоне - Часть 6 First, the advisability of the work itself was questionable. Polystyrene fibers have long been produced by electrospinning, as have fibers from many other polymers. Therefore, it would be necessary either to modify the process in order to obtain new materials or to propose new applications for electrospun polystyrene. I postponed resolving this fundamental question "for later," since there were many smaller but critical issues that needed to be addressed before the process itself could be considered established. Here are just a few of the questions that arose. How can the polystyrene be separated from the collector surface? What material should the collector (the electrode opposite the needle) be made of? What geometry should the collector have? Since the "Acetone+" solvent is a technical mixture of unknown composition, it would also be advisable to replace it with other solvents - either individual substances or mixtures of clearly defined composition. First, I consulted two colleagues who had already worked with electrospinning (albeit with PVDF rather than polystyrene). My colleague, a chemist, expressed many interesting ideas, most of which were detached from practical reality - his advice confused me more than it helped. When I tried to express more realistic ideas, he, in turn, attempted to convince me that I would not succeed and that success would necessarily require much greater complexity. For example, I suggested the following: "I can sulfonate polystyrene with sulfuric acid to obtain a cation-exchange resin from the fibers. Cation-exchange resins can remove heavy metals and many radioactive isotopes from water." My colleague replied: "You can't sulfonate with sulfuric acid - the fibers will stick together or dissolve. Sulfonating polystyrene requires simultaneous treatment with chlorine and sulfur dioxide in the gas phase. I read that in an organic chemistry laboratory manual! Also, I read that sulfonated polystyrene is soluble in water." I pointed out that chlorine was the first chemical warfare agent successfully used on the battlefield. Sulfur dioxide is less toxic than chlorine, but it is still highly unpleasant to work with. We didn't have cylinders of chlorine or sulfur dioxide, nor did we have conditions that would allow us to work safely with these substances. My colleague seemed more interested in generating ideas than in actually implementing them in our laboratory. The physicist colleague helped as much as he could. In particular, he said that in their experiments the electrode had been covered with aluminum foil, and that the material obtained by electrospinning could be easily separated from the collector surface after drying. Later, I found a video on electrospinning in which the author carefully separated the resulting material from aluminum foil using a thin metal ruler. I soon realized that smooth aluminum foil was a better collector than a metal mesh, and that an even better option was a thick steel sheet. Aluminum foil is fragile: it tears and wrinkles easily, which makes separating the resulting polystyrene from the electrode difficult. A mesh is convenient for preliminary experiments - it can be placed under a microscope without separating the polystyrene, and the holes allow the coating structure to be observed in transmitted light. However, these same holes make it difficult to separate the coating from the electrode. The most convenient collector turned out to be a thick steel sheet brought by the chemist colleague. There was no risk of tearing or wrinkling it during operation. I also tried using a cylindrical tin can as a collector, but this proved unsuccessful. The coating was highly uneven, and the cylindrical surface made separation of the electrospun material more difficult. A major problem was - and remains - the "splashes" of polymer solution that are pulled from the needle by the electric field and reach the collector before they have time to evaporate. As the physicist colleague put it, "The needle spits." As a result, the liquid solution glues together the polystyrene fibers that have already settled on the collector, sometimes partially dissolving them. In such areas, the white coating becomes locally darkened, indicating that it is wet - this is clearly visible to the naked eye. Under the microscope, glued and partially dissolved fibers can be observed in these regions. Visually, the polystyrene in such places resembles a film of hardened glue. In contrast, in the absence of splashing, electrospun polystyrene resembles a loose layer of cotton wool. I attempted to increase the distance between the electrodes to give the fibers more time to elongate under the repulsion of like charges and to dry. However, as the needle was moved farther from the collector, fiber formation ceased - the potential difference was no longer sufficient to generate a Taylor cone. Increasing the polymer concentration was also possible only up to a certain limit. As the polymer concentration increased, the surface tension of the solution increased as well. Eventually, the electric field became insufficient to pull a fiber from the droplet. Moreover, even when fibers initially formed normally, the solvent gradually evaporated from the droplet at the tip of the needle, increasing the polymer concentration and complicating the formation of new fibers. At the same time, the fresh solution emerging from the needle did not flow downward but instead flowed into the large, viscous droplet at the tip. I occasionally observed droplets up to half a centimeter in diameter. These droplets often burst, splashing onto the collector, which was already covered with fibrous polystyrene. Using a needle with a larger inner diameter at the same solution flow rate increased splashing. Another important parameter is the solution flow rate. It must be low enough to allow the solution leaving the needle to evaporate on its way to the collector and to prevent the formation of large droplets at the needle tip. However, if the flow rate is too low, the experiment time increases significantly - and power outages are frequent. A balance must therefore be found. If the flow rate is too low, there is also an increased risk that the solution will solidify inside the needle or at its outlet. Temperature is another important factor. The warmer the air in the laboratory, the faster the solvent evaporates. I placed an electric heater next to the setup, which led to a dangerous incident. The nut on the pastry syringe came off, carrying with it the syringe containing the polystyrene solution and the high-voltage electrode connected to the needle; all of this fell near my feet. At first, I assumed that the failure was caused by thermal stress due to uneven heating of the setup. However, I later discovered that the top of the pastry syringe had partially melted and was deforming under infrared radiation from the heater. In addition, heating sometimes caused the polystyrene solution to solidify inside the needle, forcing the process to be stopped and the needle replaced. When I redirected the heater away from the setup and toward the wall of the fume hood, I soon heard a cracking sound-the tile had overheated and begun to crack. In subsequent experiments, I continued to use the heater, but with caution. I could not dispense with it entirely: the laboratory was cold, and low temperatures promoted splashing. In addition to incomplete drying, the opposite problem also arose: the formation of "dendrites" or a "beard" - solidified polystyrene fibers that did not detach from the needle. I removed these dendrites with a long dielectric rod, but they re-formed repeatedly. Using the heater increased dendrite formation. Another problem was that the polystyrene fibers did not deposit exclusively on the front surface of the collector electrode. I soon noticed that fibers had formed a web on the Petri dish placed under the needle to collect spilled solution. They were also deposited on retort stands, on the bottom and side walls of the hood, on wires, and, of course, on the back side of the collector. When I used an iron sheet as a collector, the fibers initially settled on the front surface. However, once this surface became covered with a layer of dielectric fibers, polystyrene began to deposit on the back side of the electrode, forming a continuous, though uneven, layer. In the next experiment, I covered the back of the electrode with a sheet of paper, bending its edges downward at right angles. As a result, polystyrene fibers partially covered the paper as well. The problem was ultimately solved by increasing the width of the electrode. In addition, there should be no foreign surfaces near the needle and collector - such as the walls of the fume hood, retort stands, or the dark plastic sheets I used as a background to improve video quality. Fibers accumulated on all of these surfaces, reducing the amount of polystyrene collected on the electrode. Incidentally, some fibers even adhered to my hands and smartphone when I approached the high-voltage needle too closely. My colleagues reported similar experiences. The three-part syringe also caused difficulties. Unlike a two-part syringe, a three-part syringe has a rubber seal on the plunger. When I attempted to use such a syringe, the pump frequently jammed. I concluded that the problem was caused by swelling of the rubber seal in the organic solvent. However, after prolonged use, even the two-part syringe occasionally began to jam: its plunger became deformed over time, leading to imbalance in the mechanism. The problem was resolved by replacing the 5 mL syringes with 2 mL ones. Although the smaller syringes required more frequent refilling, they operated much more reliably. |

Electrospinning: Solution of Polystyrene in Surrogate Acetone |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|