Chemistry and Chemists № 2 2025

Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts

| Content | Chemistry experiments - video | Physics experiments - video | Home Page - Chemistry and Chemists |

|

Chemistry and Chemists № 2 2025 Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts |

Experiments with Thermite - pt.30 Chemist |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

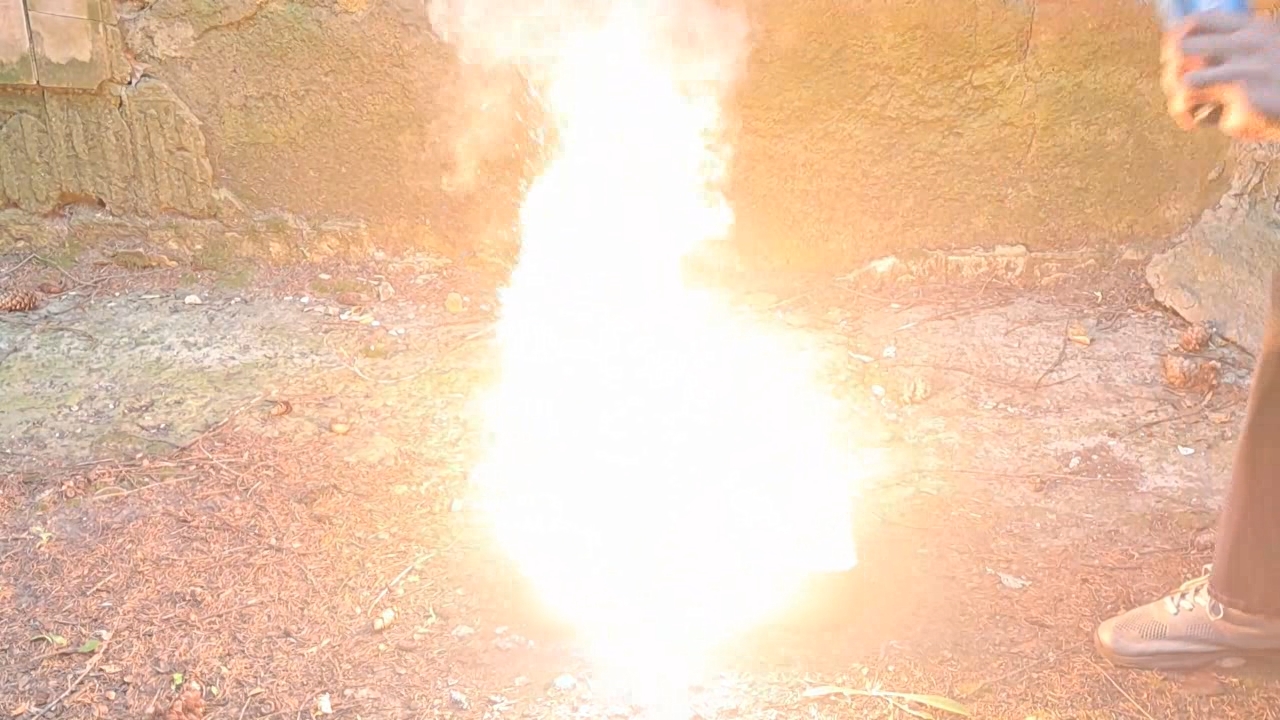

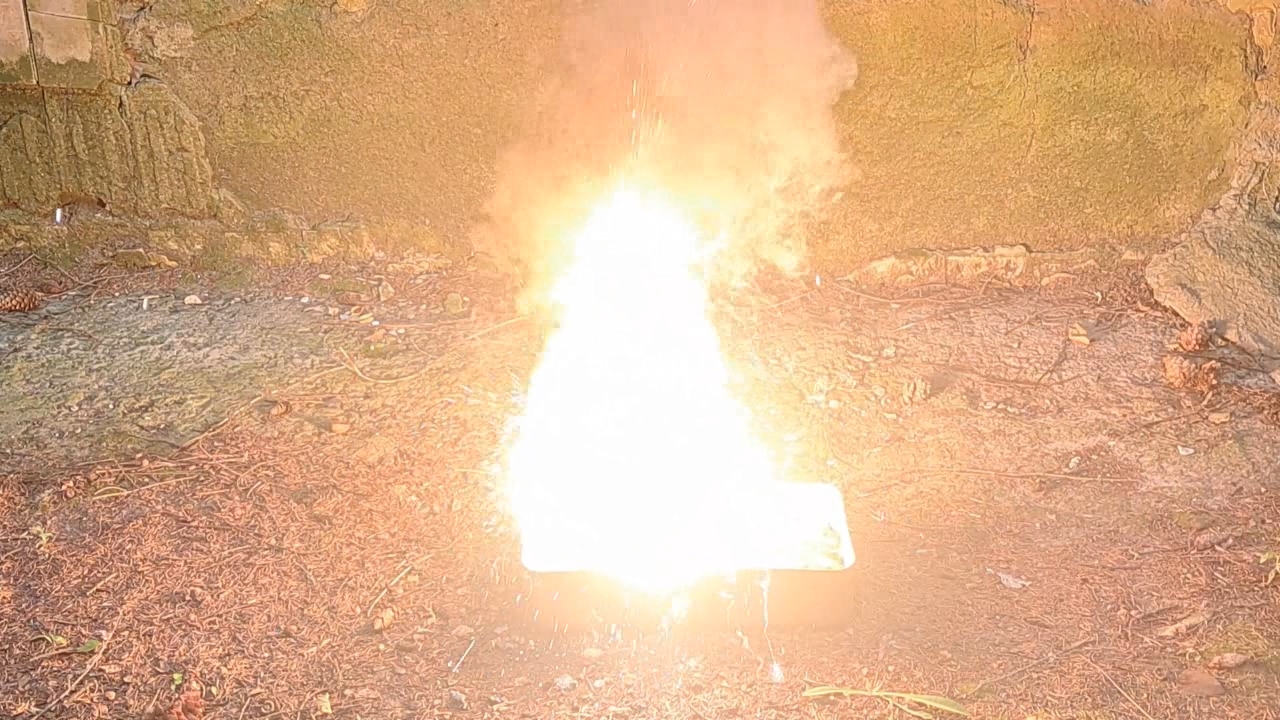

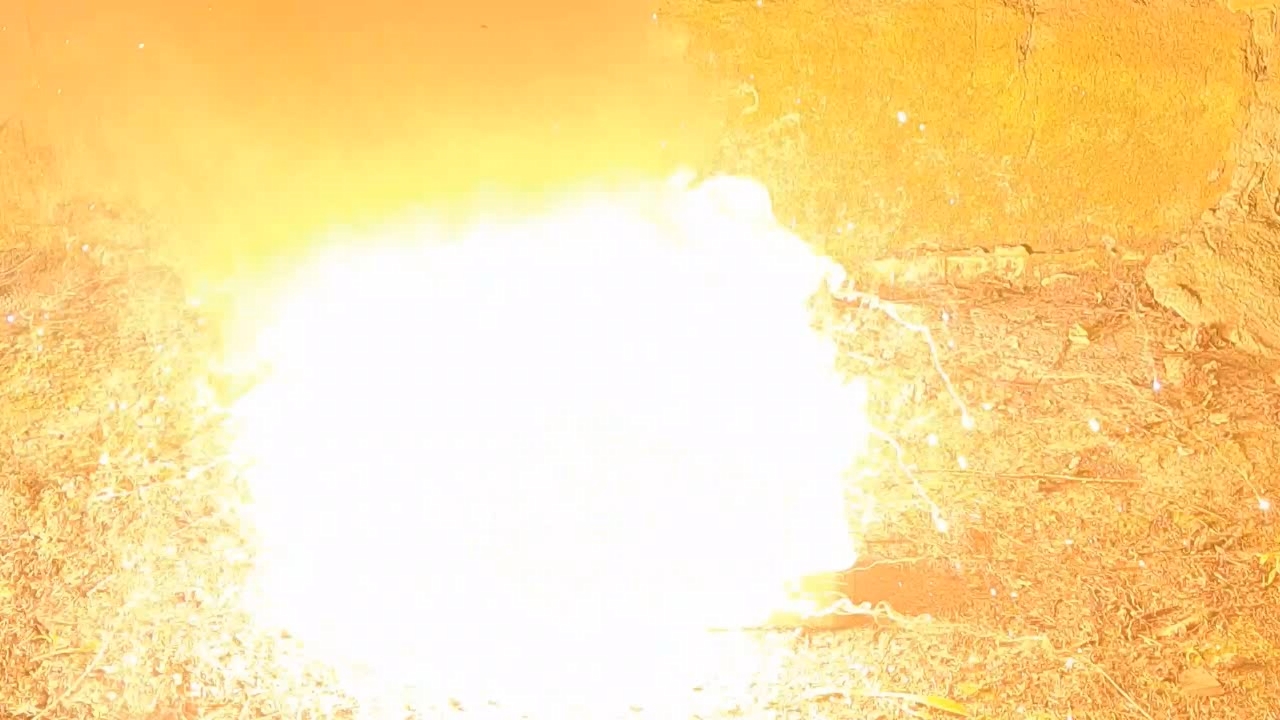

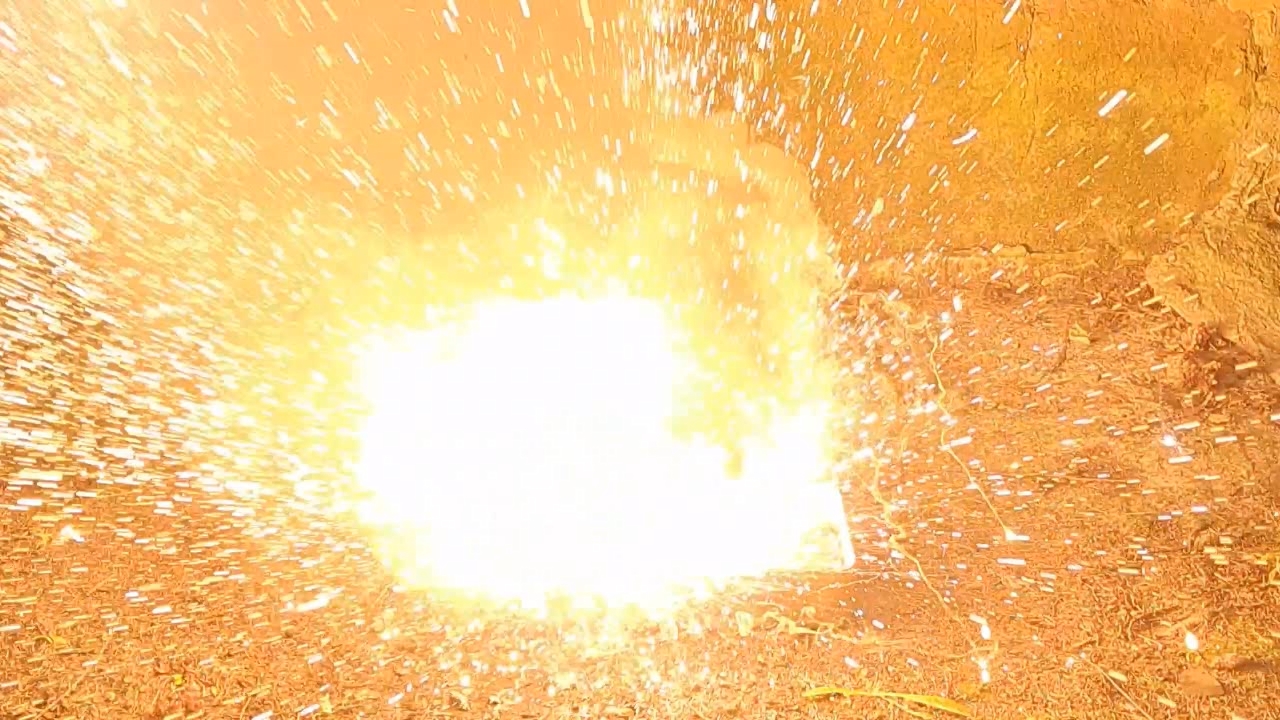

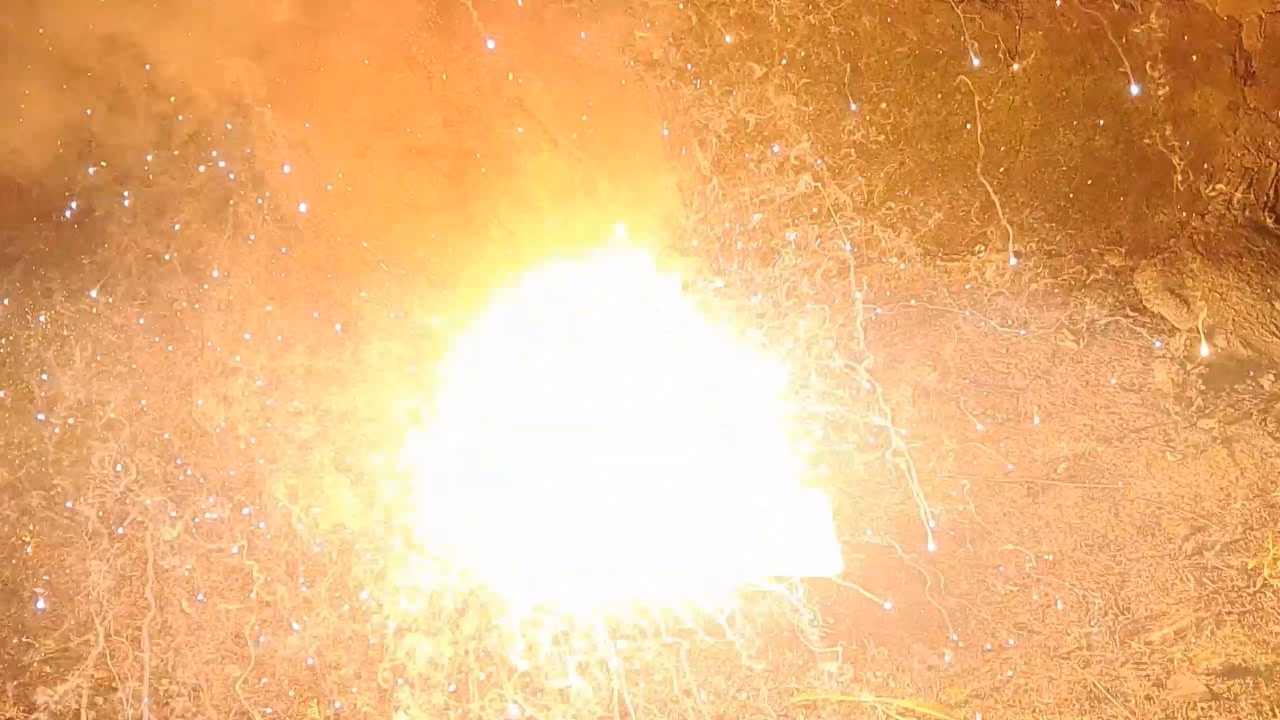

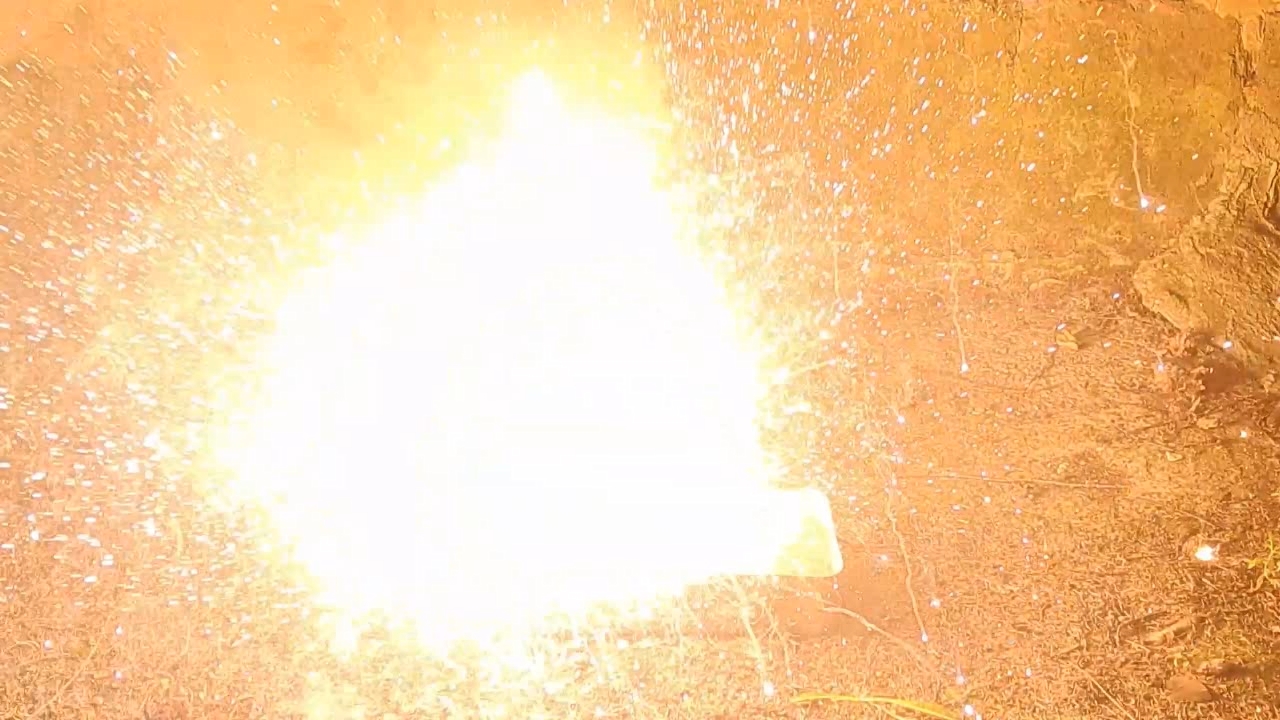

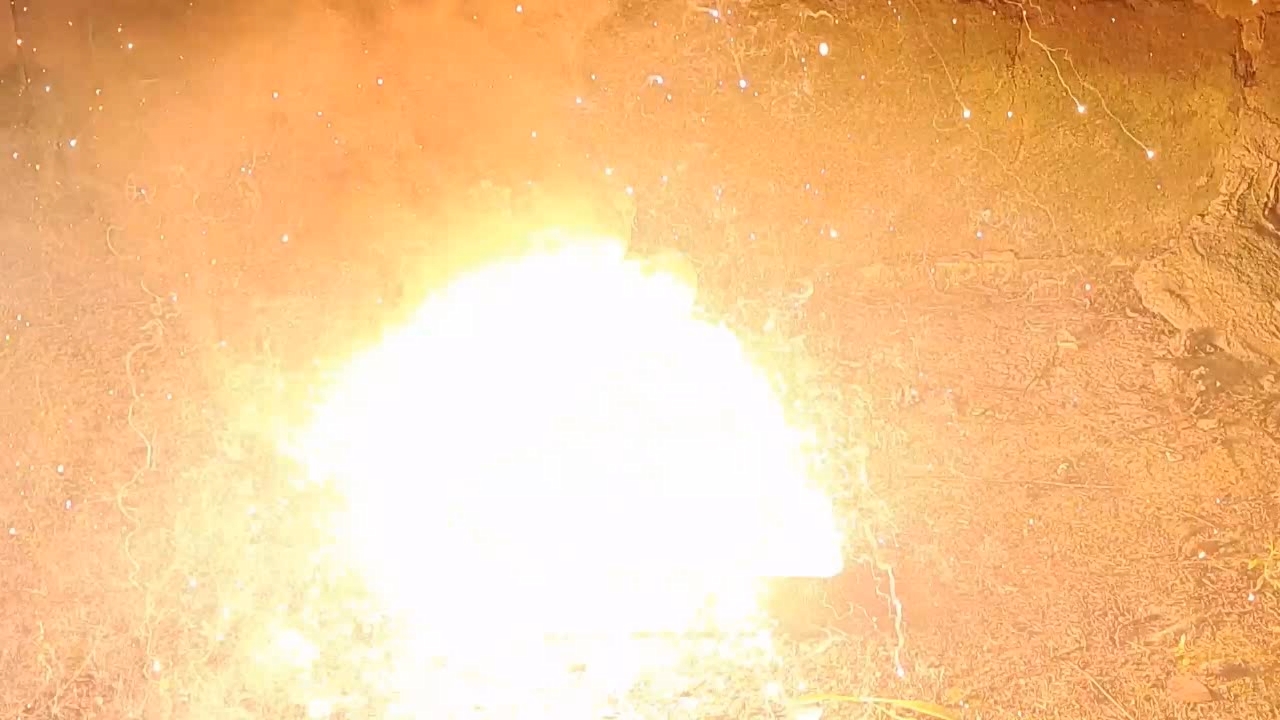

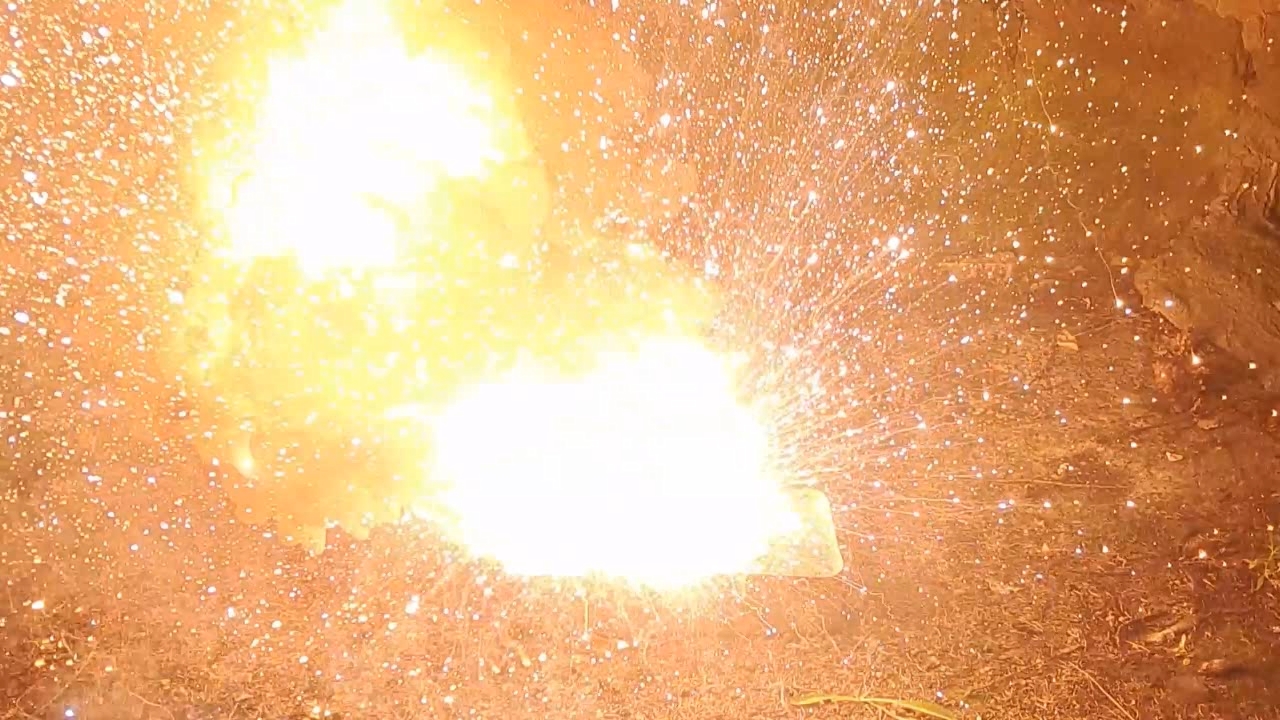

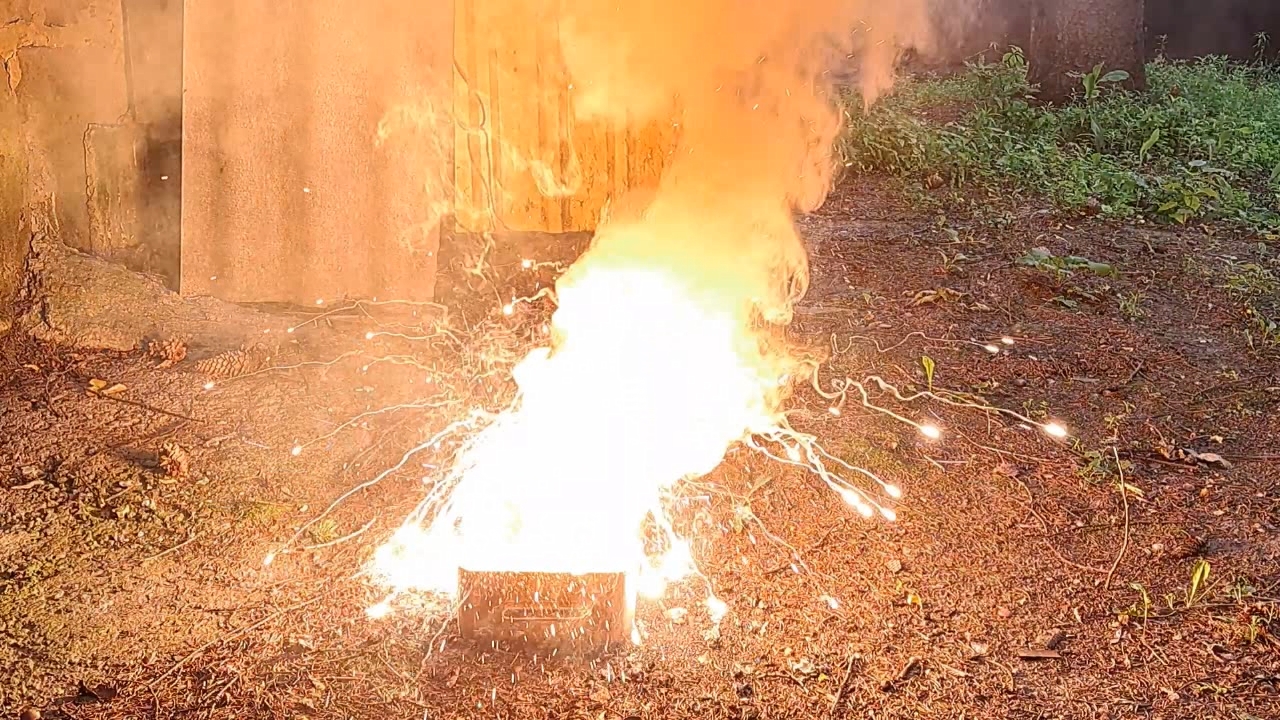

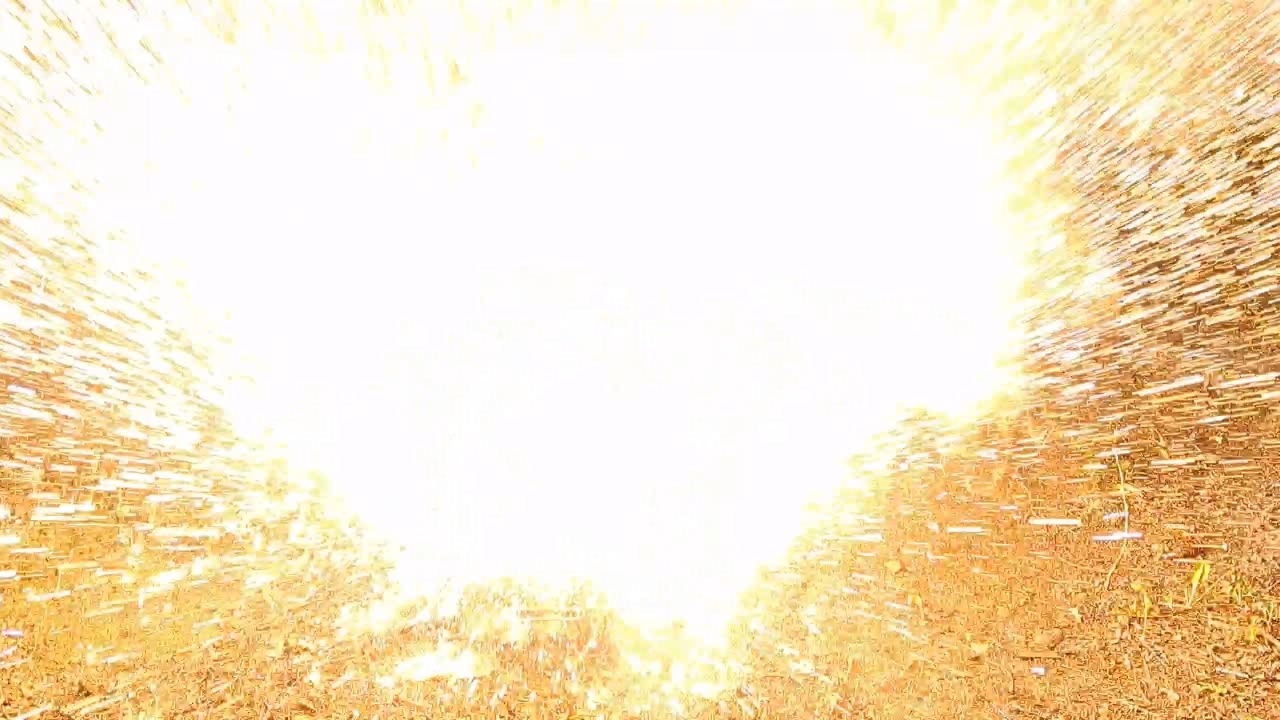

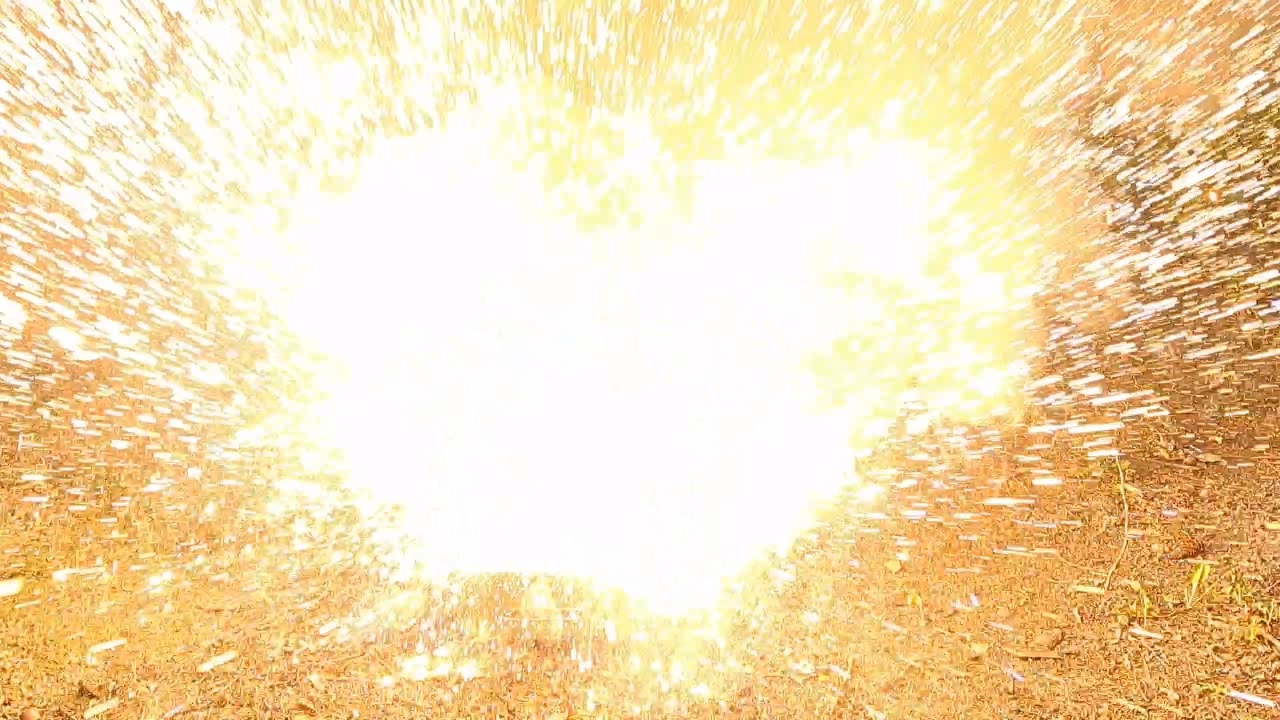

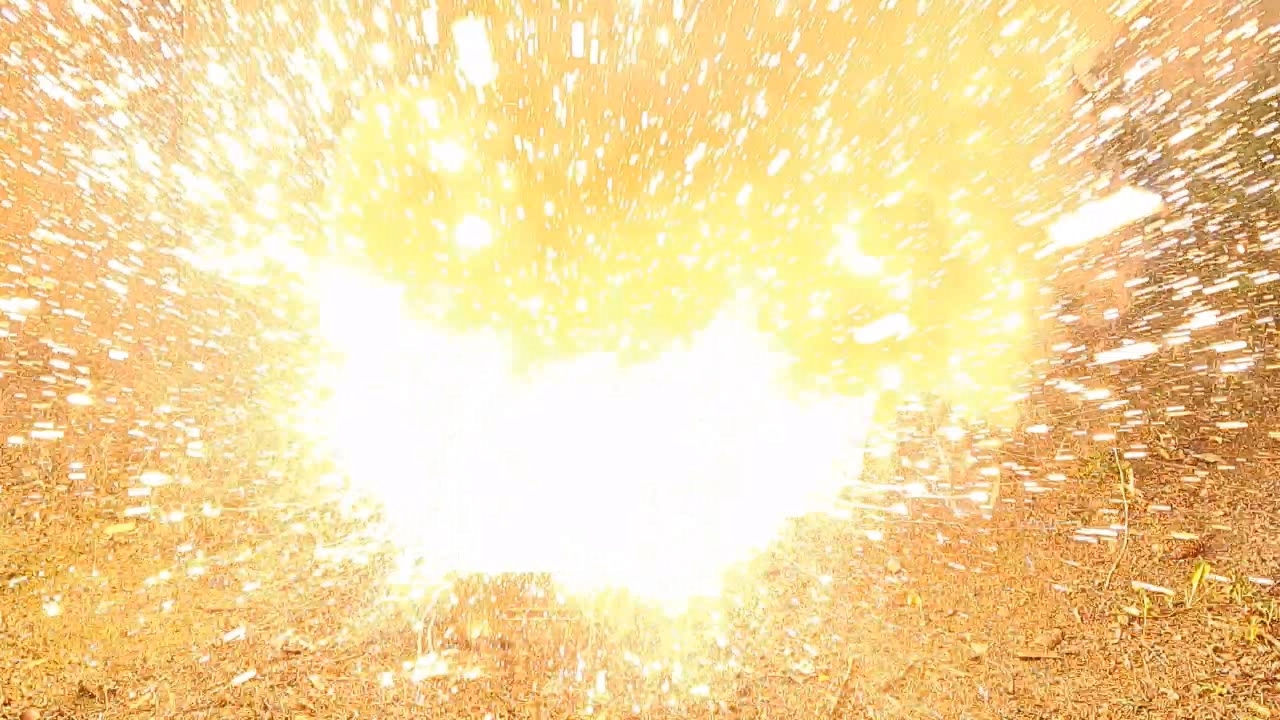

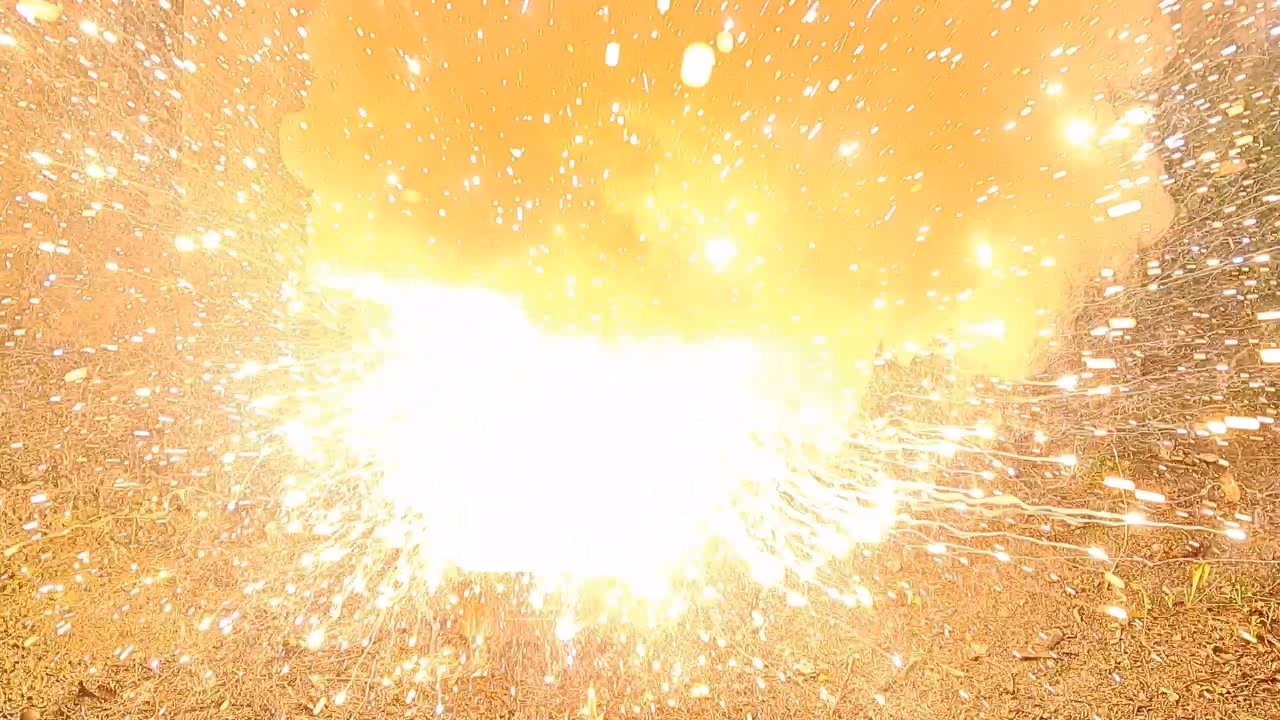

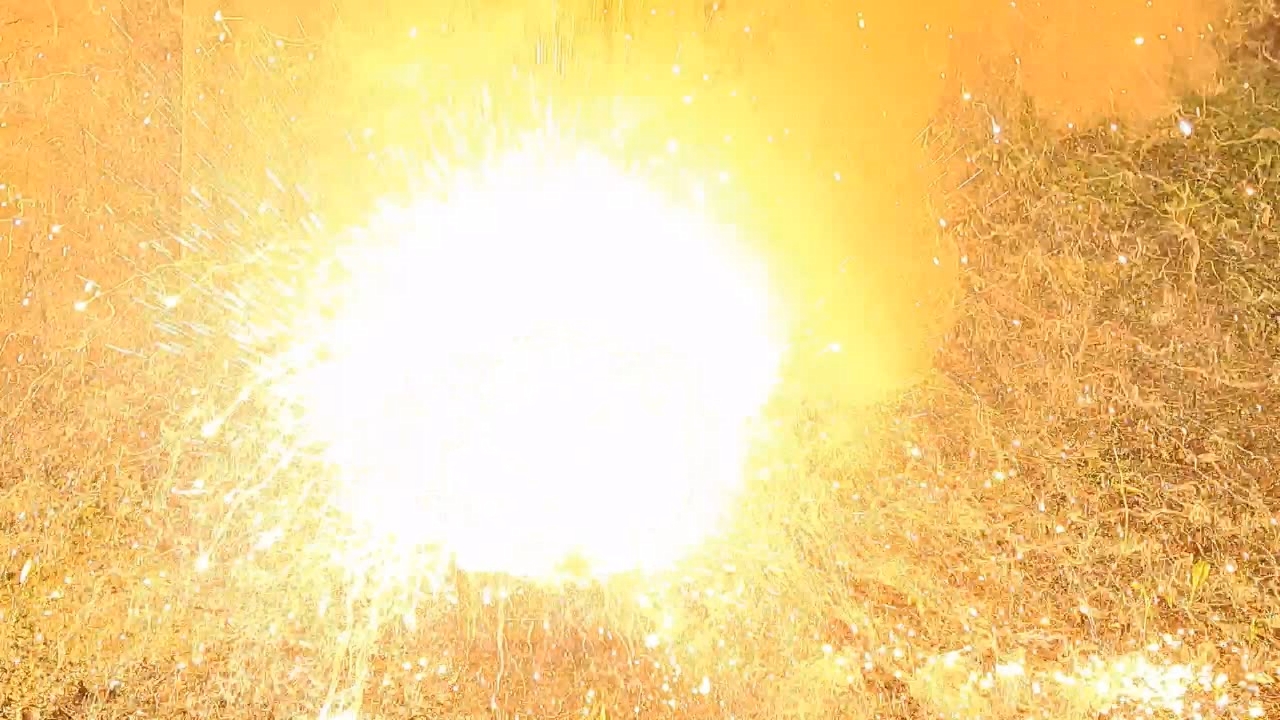

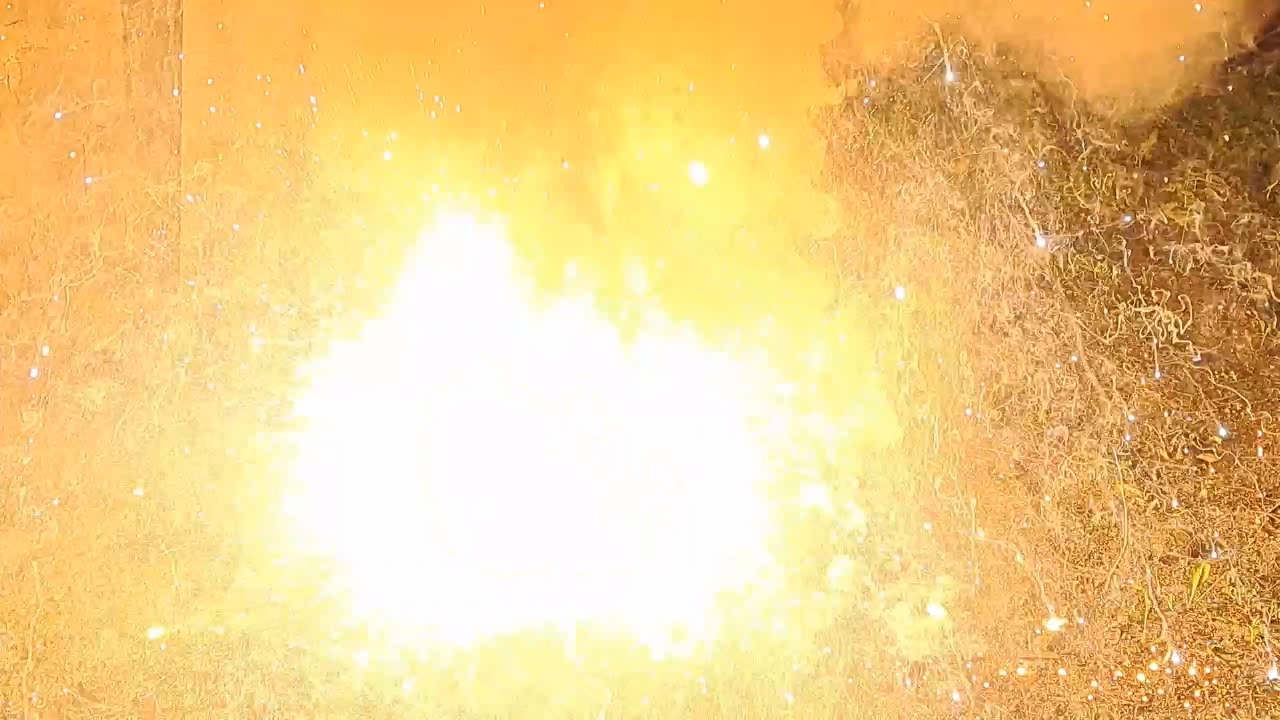

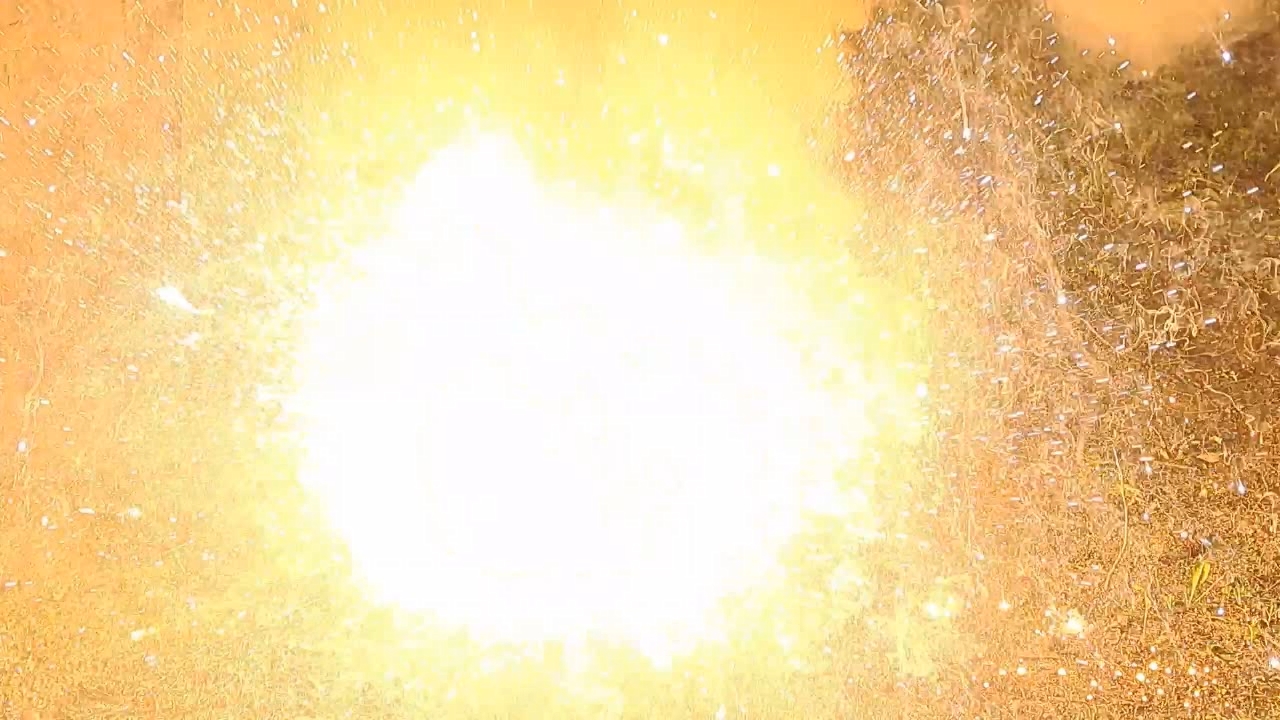

Combustion of Thermite: Iron(II, III) Oxide/Aluminum/Magnesium (Fe3O4/Al/Mg) - Part 30

The idea had been in my mind for a long time. Just a few weeks ago, I was planning to prepare Fe3O4/Al thermite with a large amount of magnesium added. While conducting the experiment described in Part 27 of this article, I initially intended to prepare the following mixture:

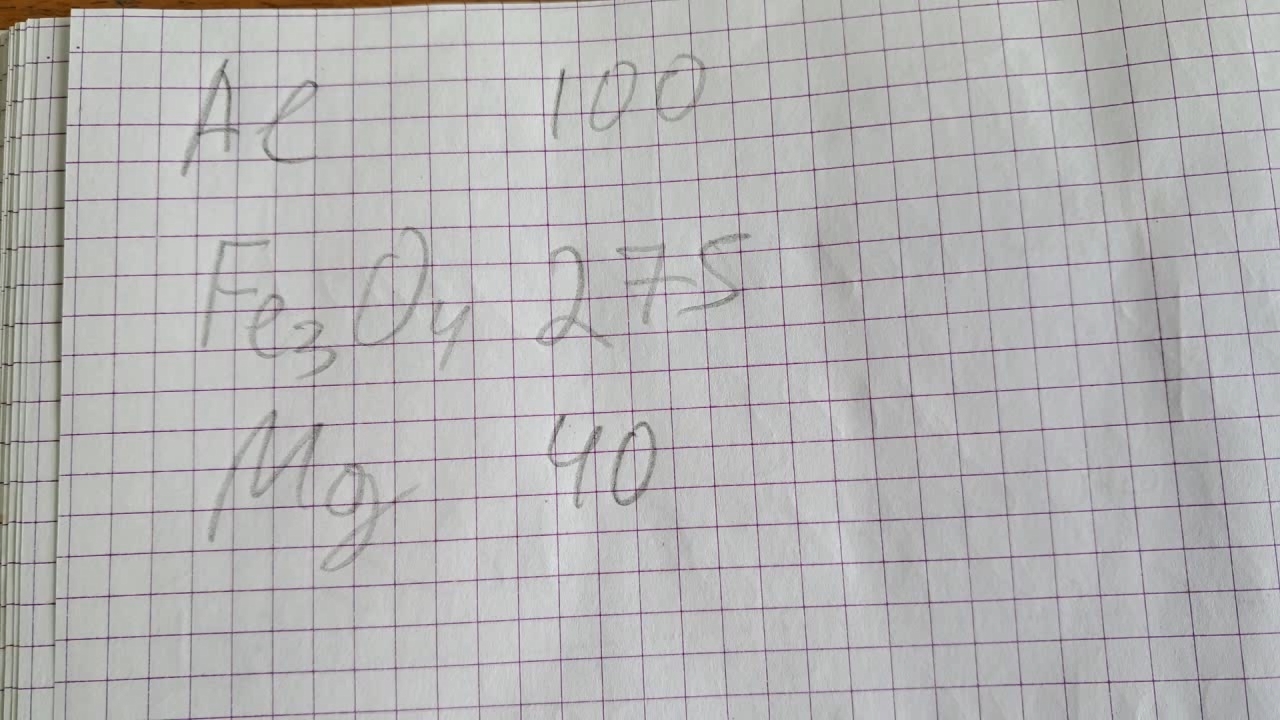

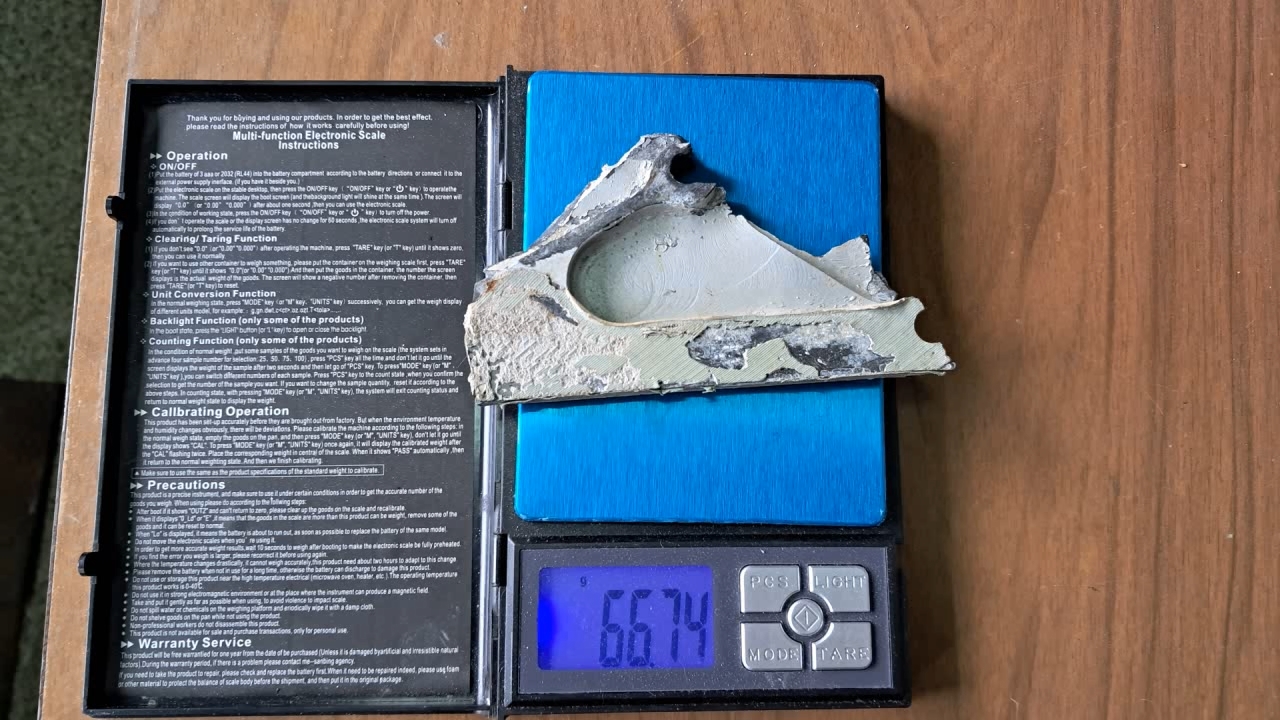

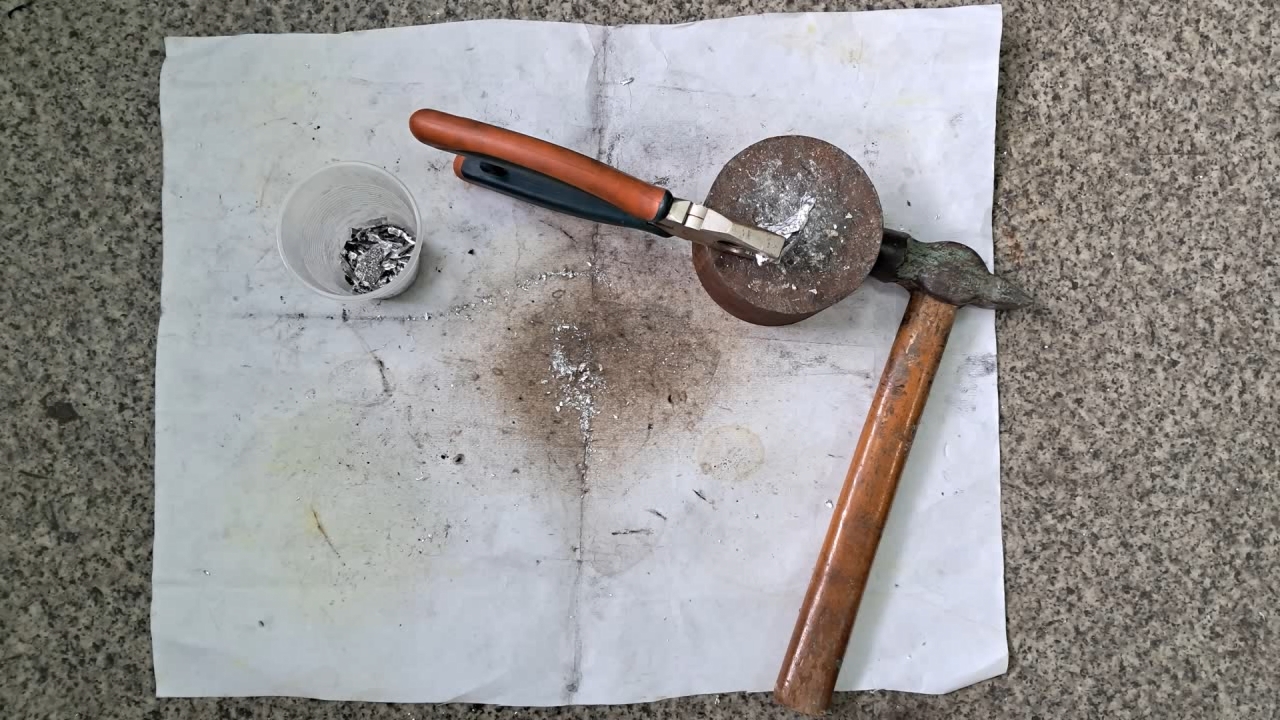

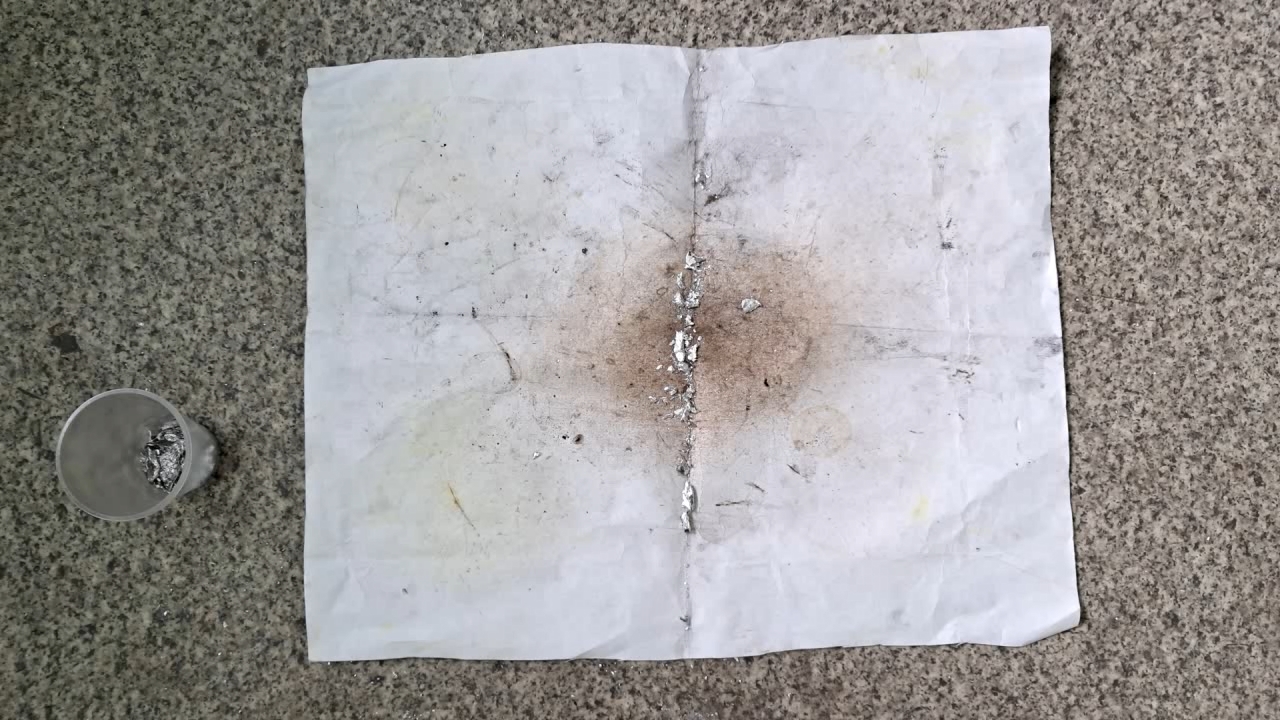

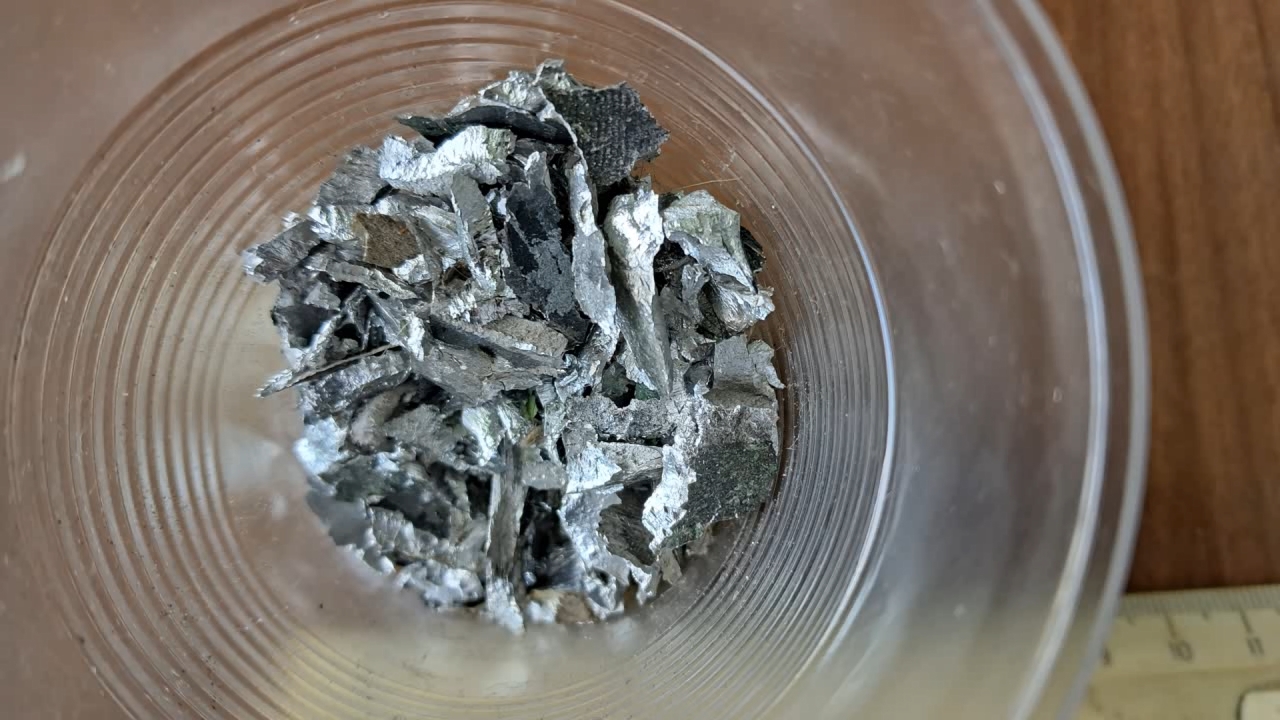

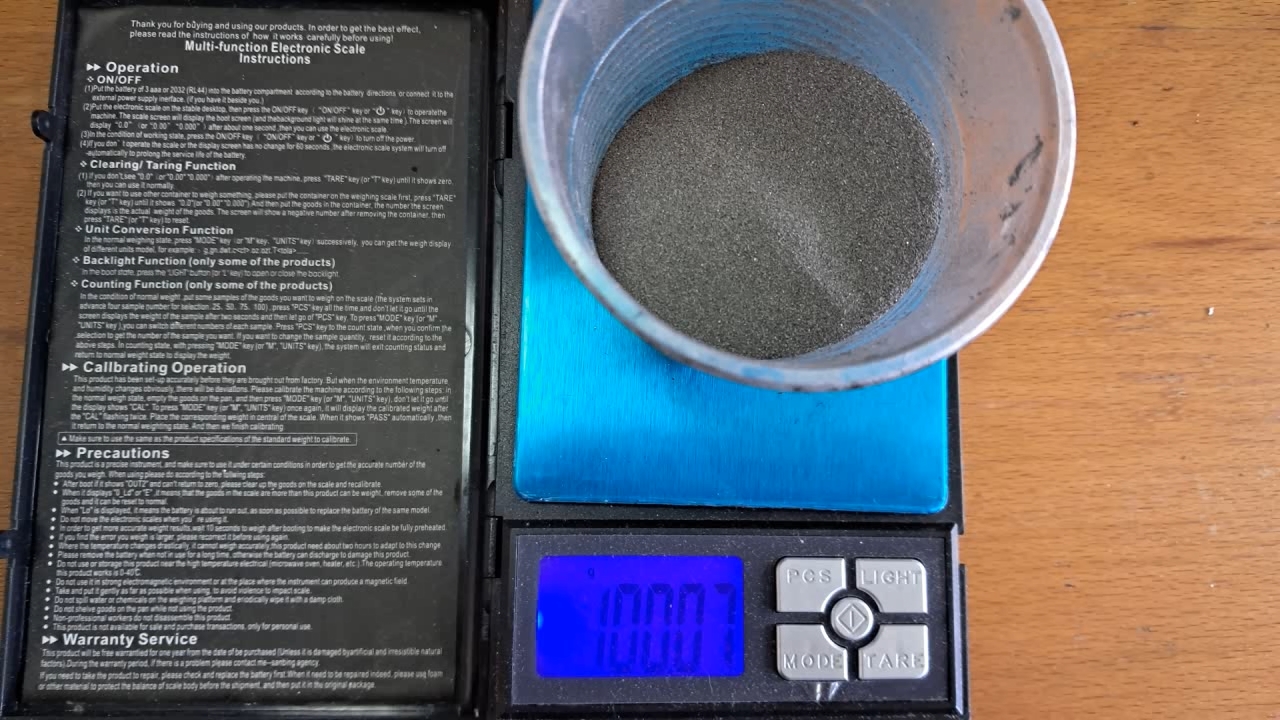

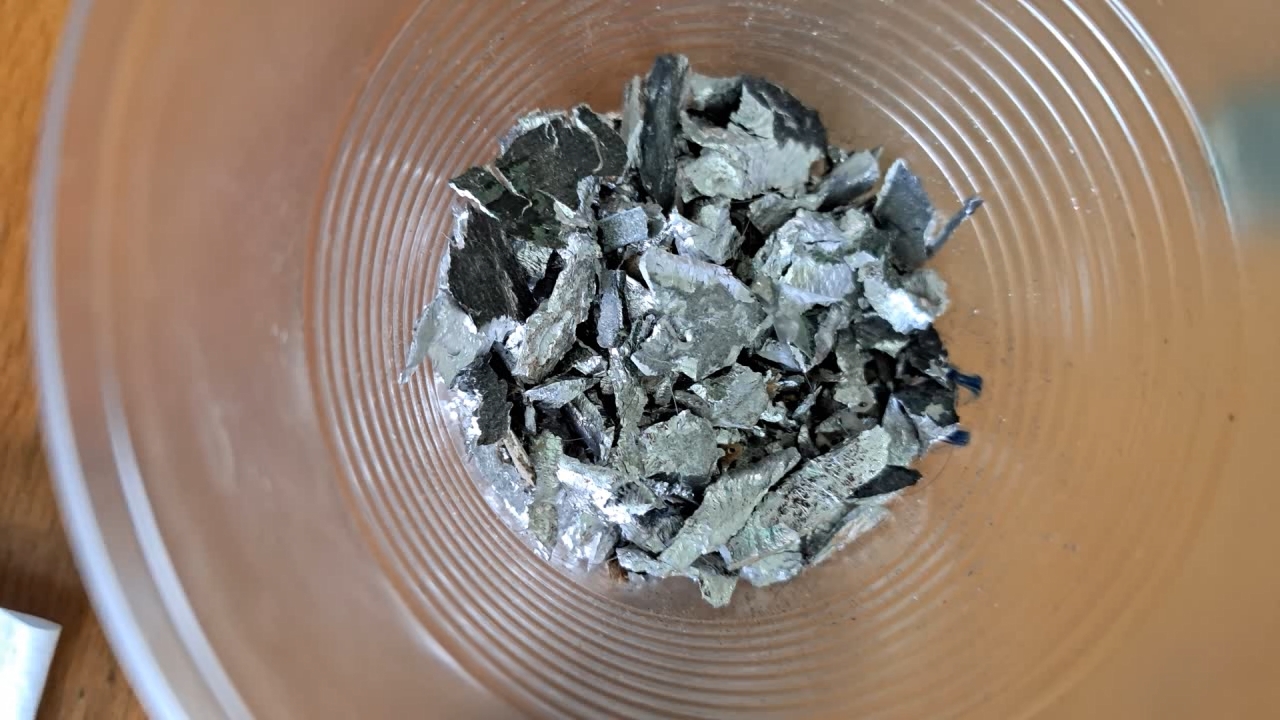

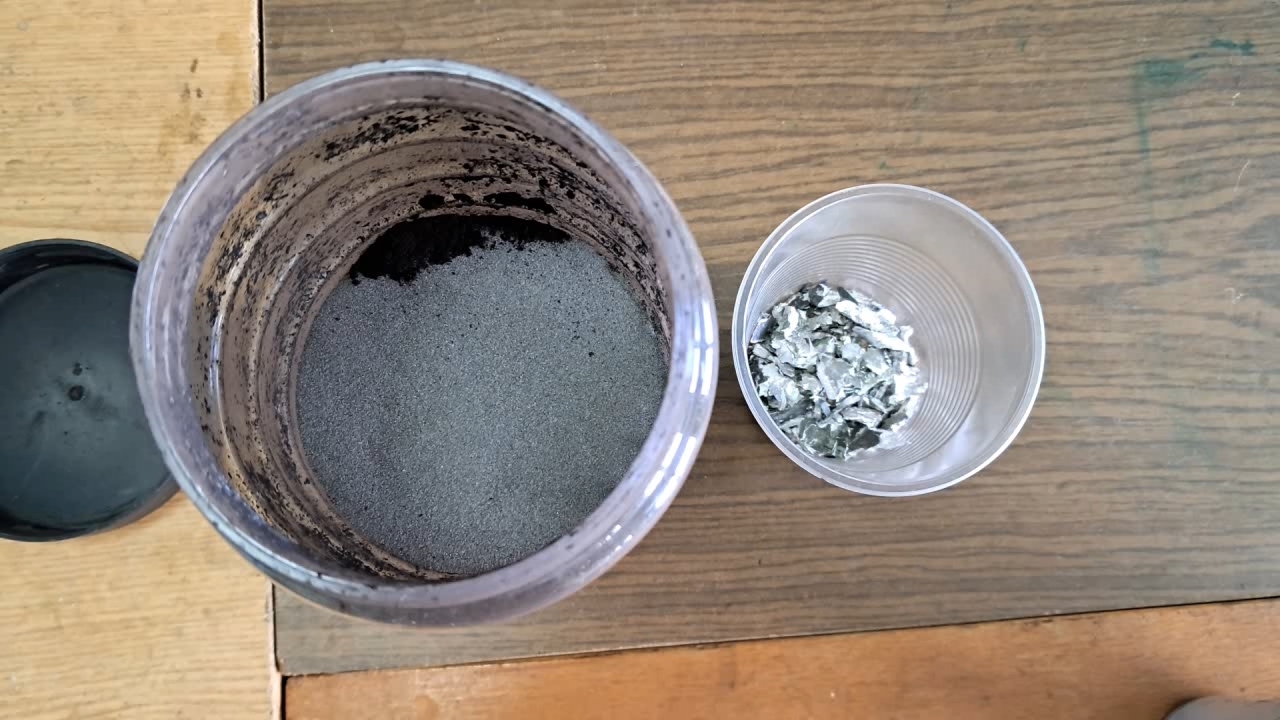

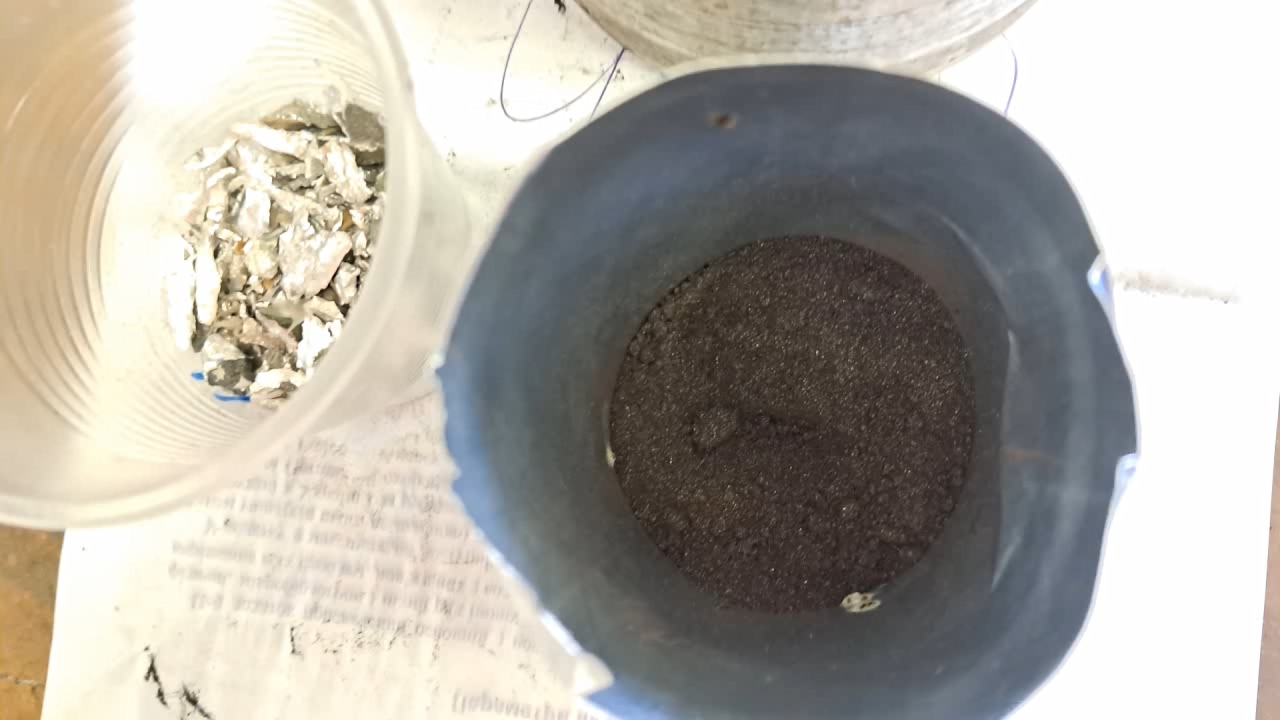

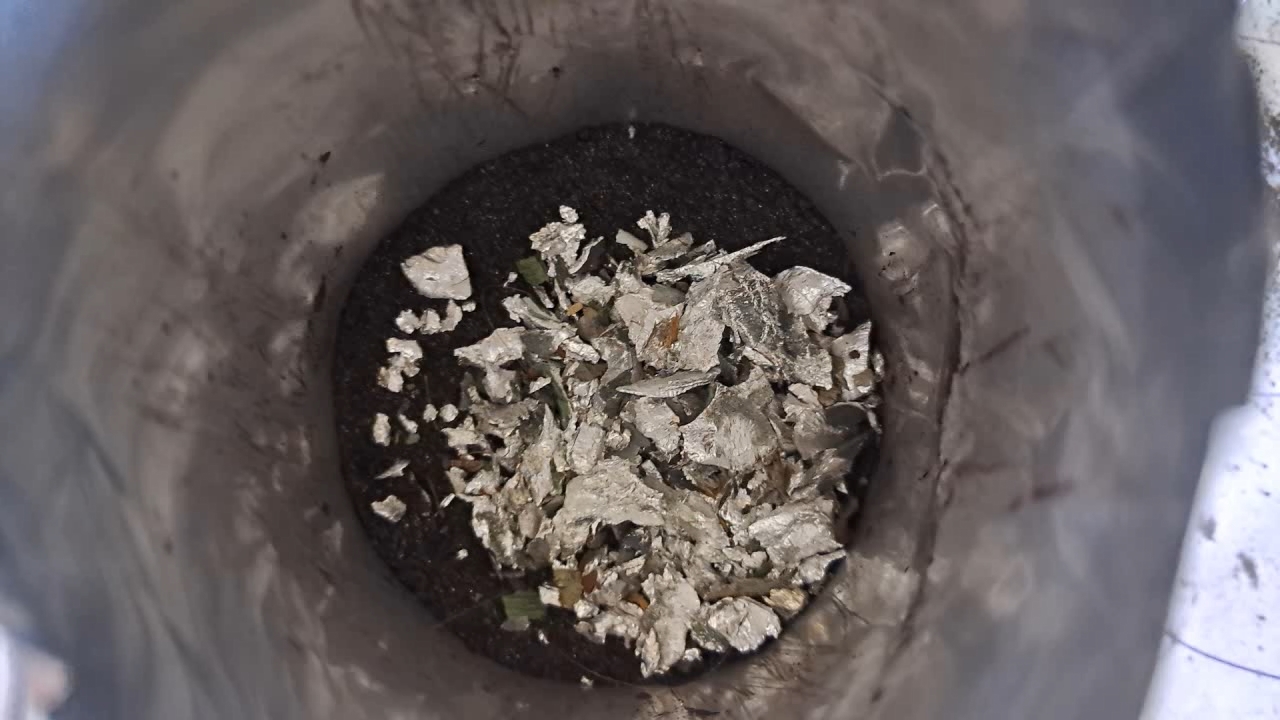

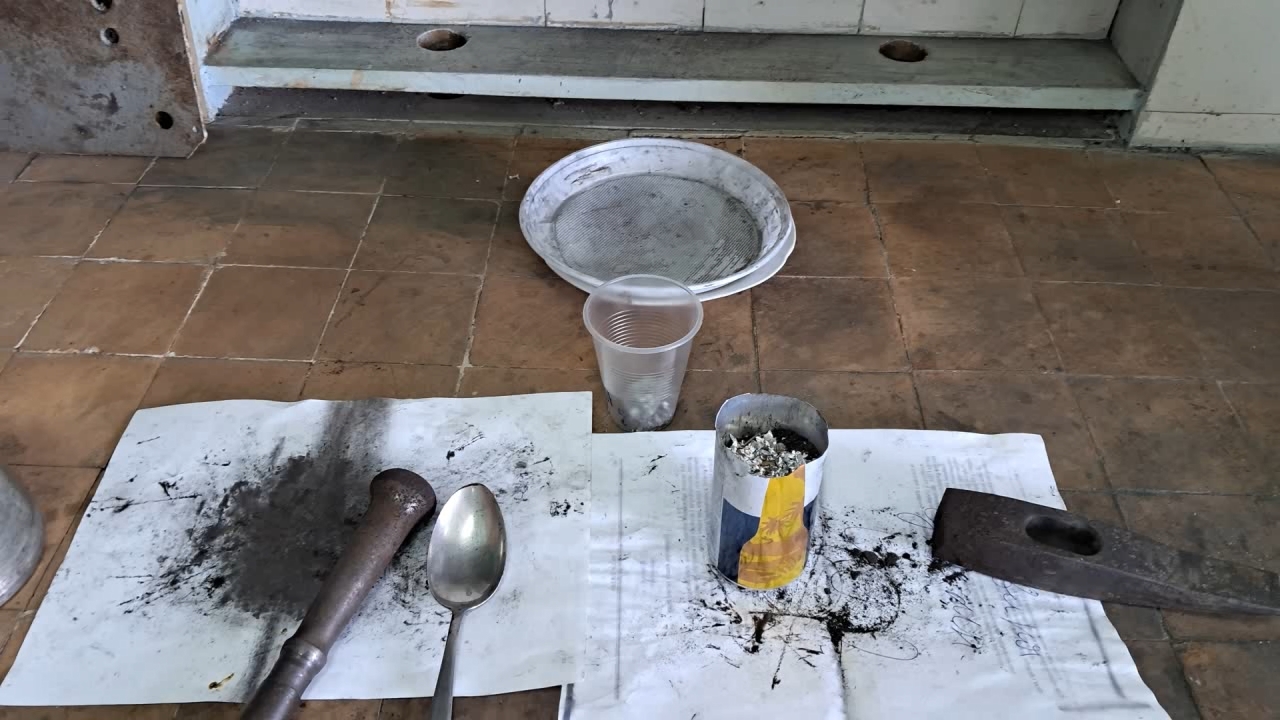

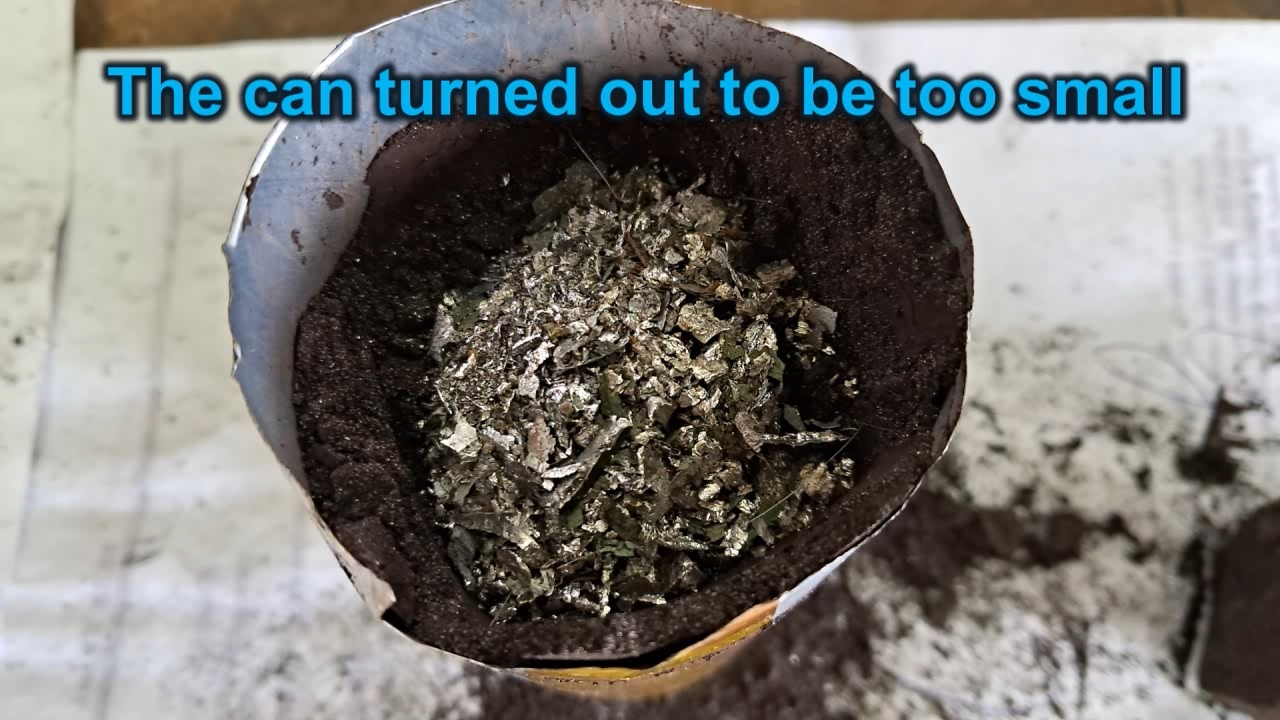

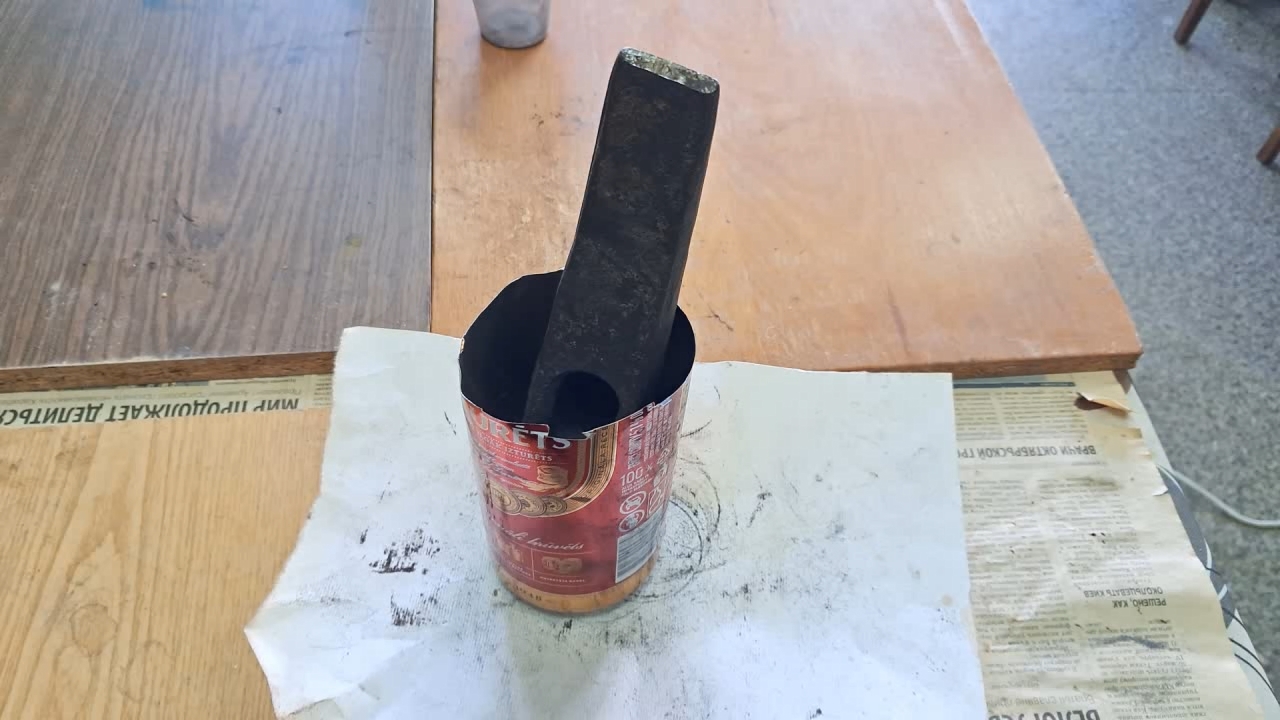

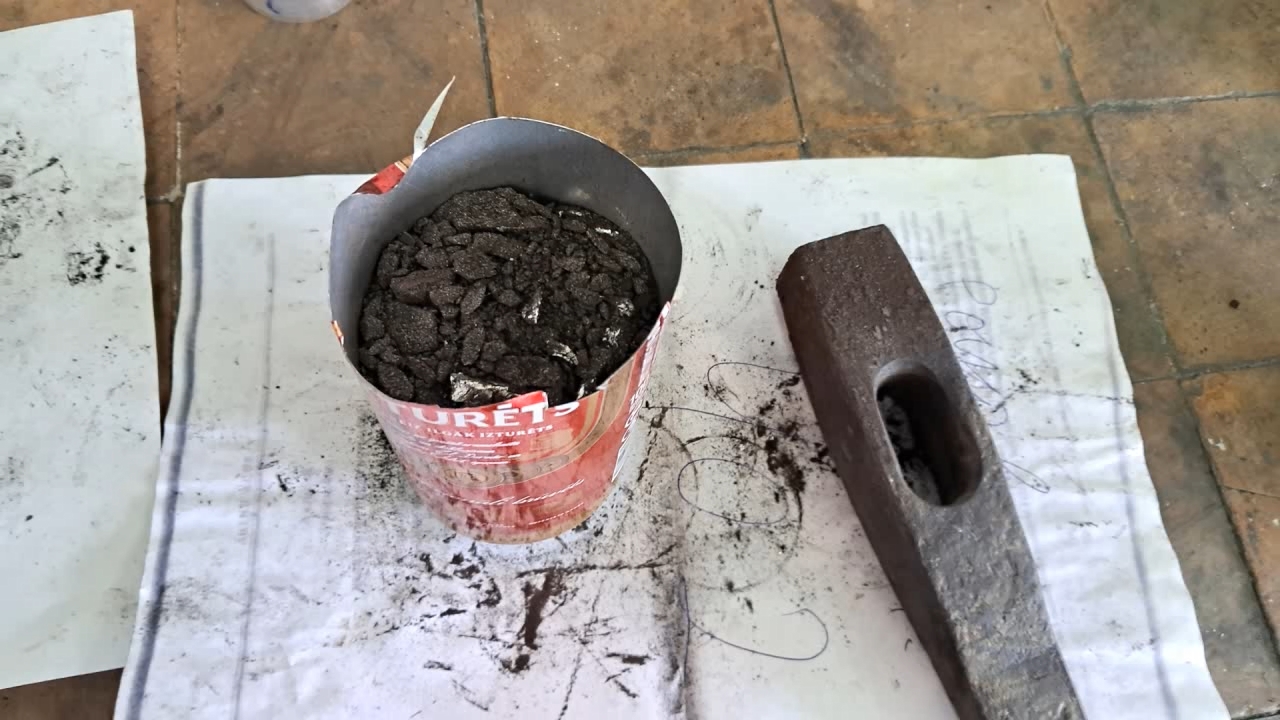

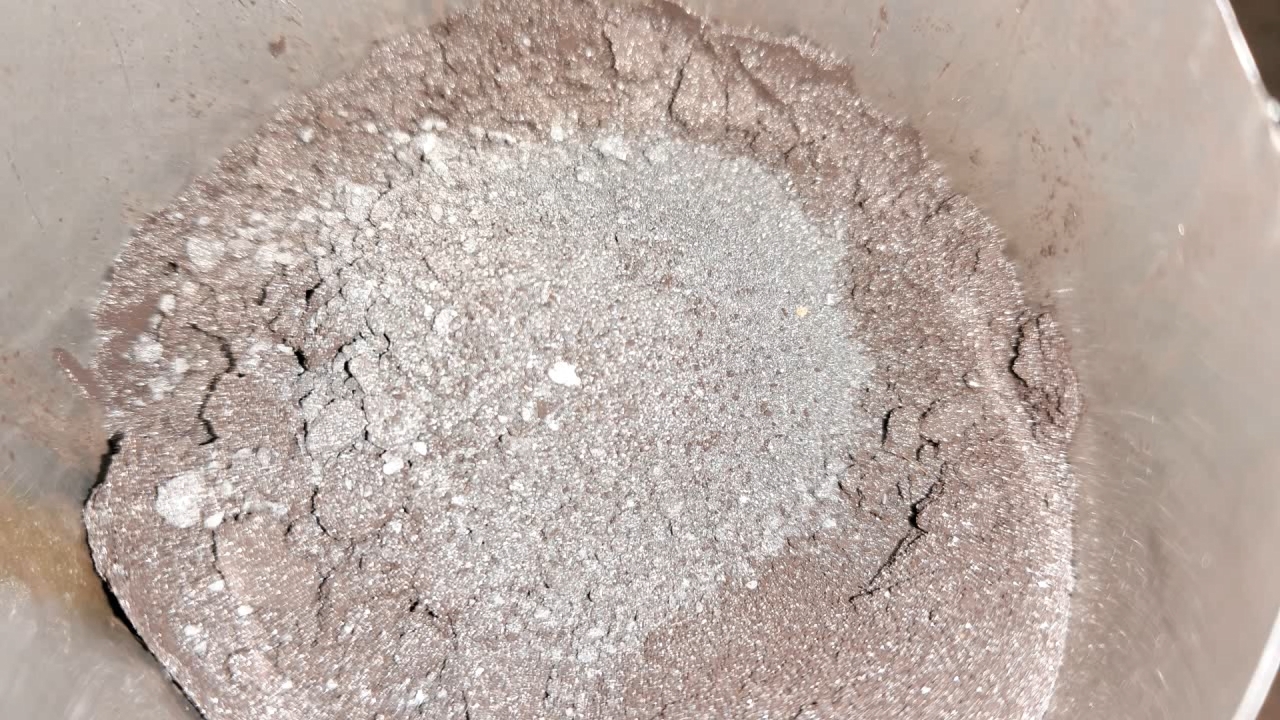

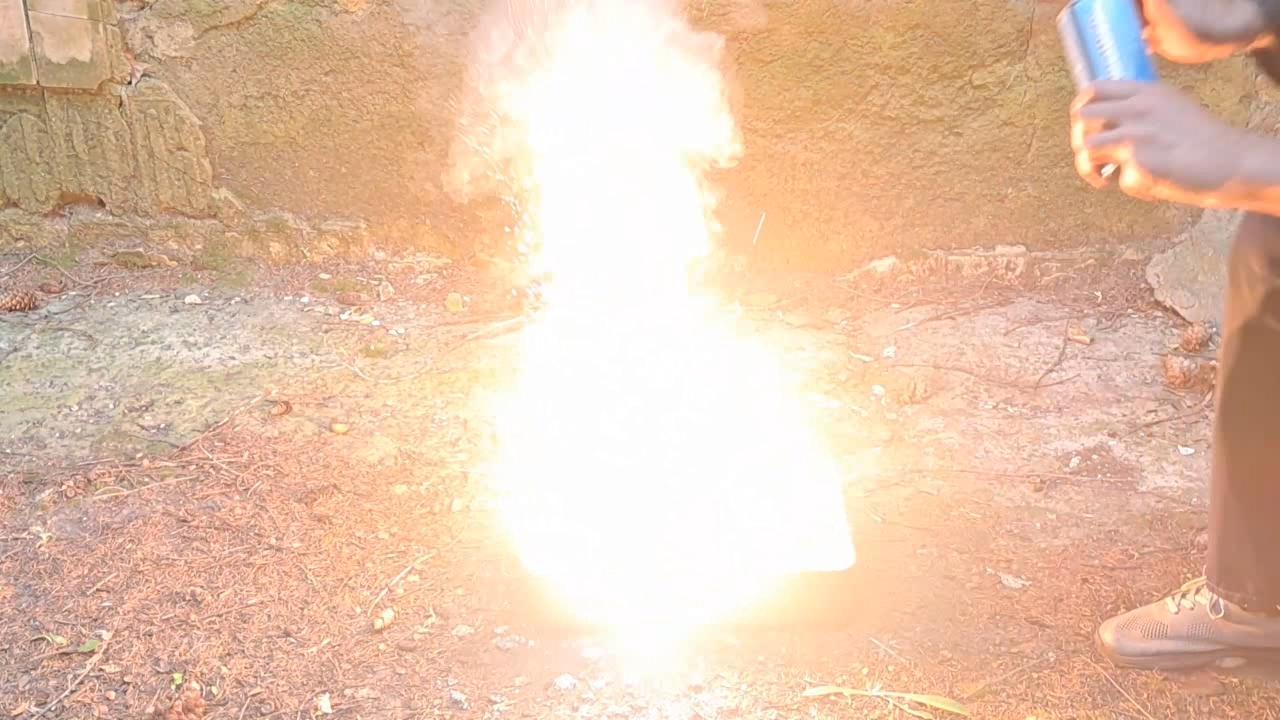

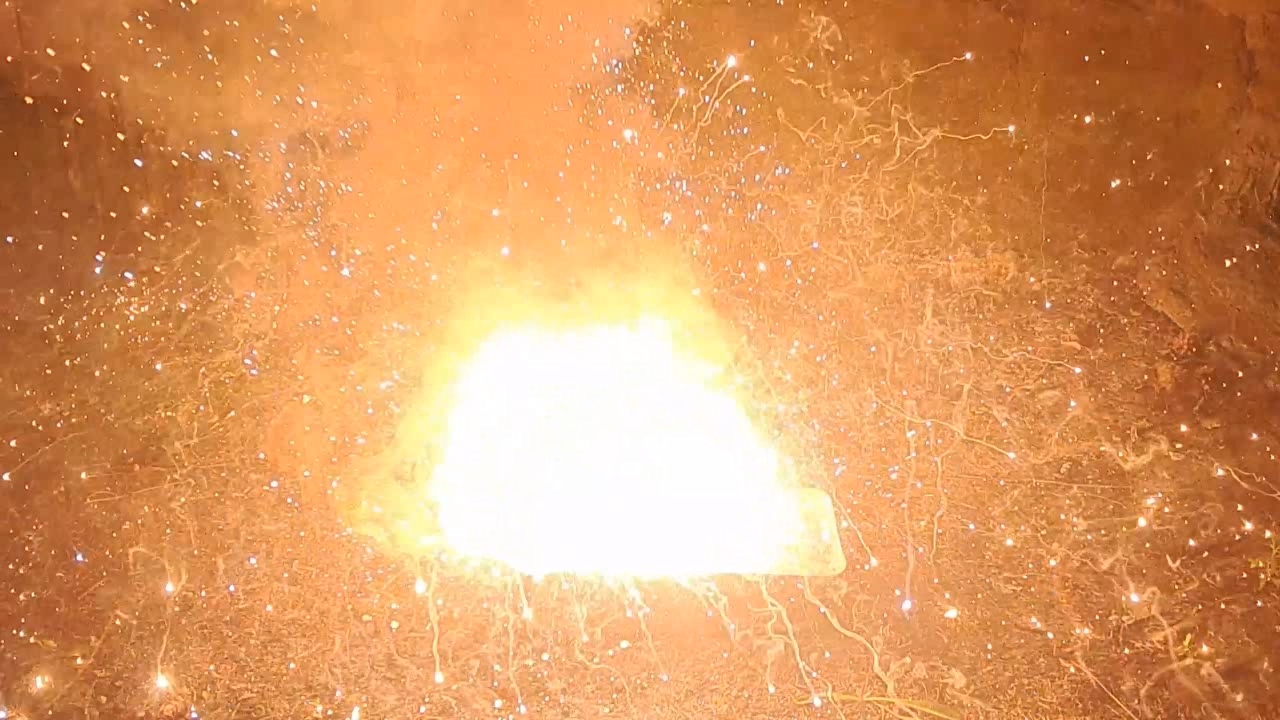

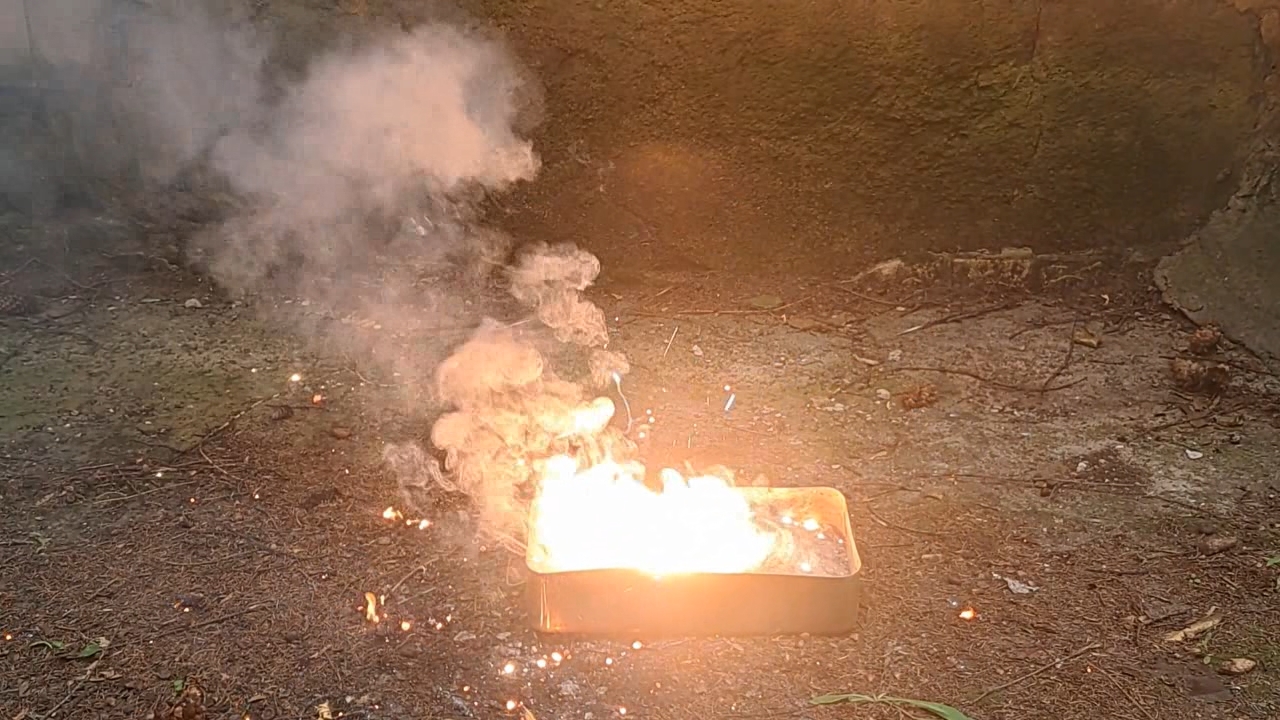

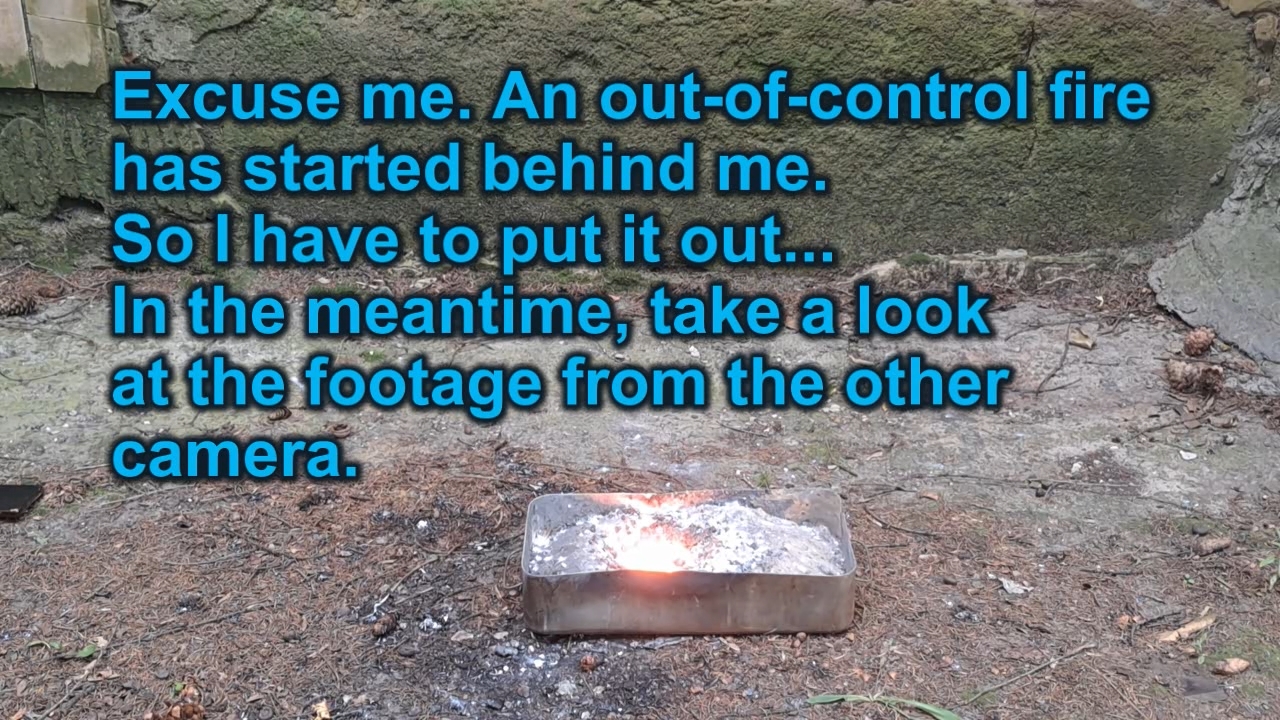

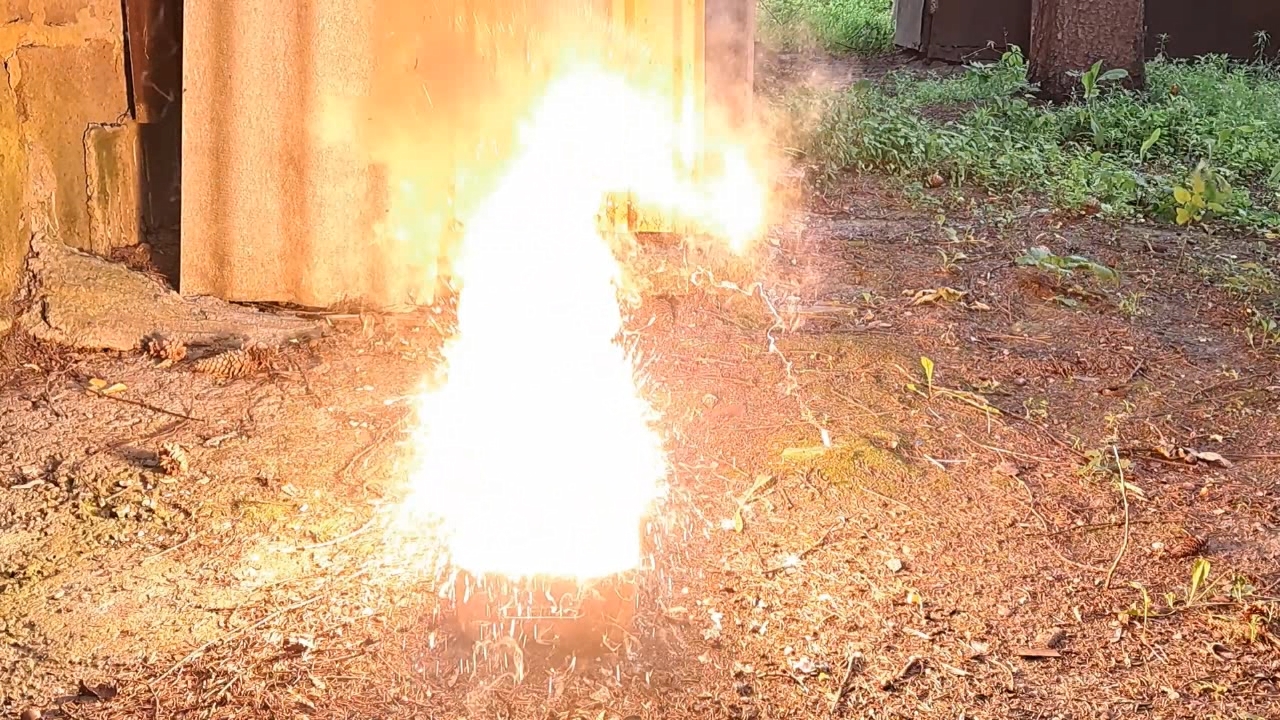

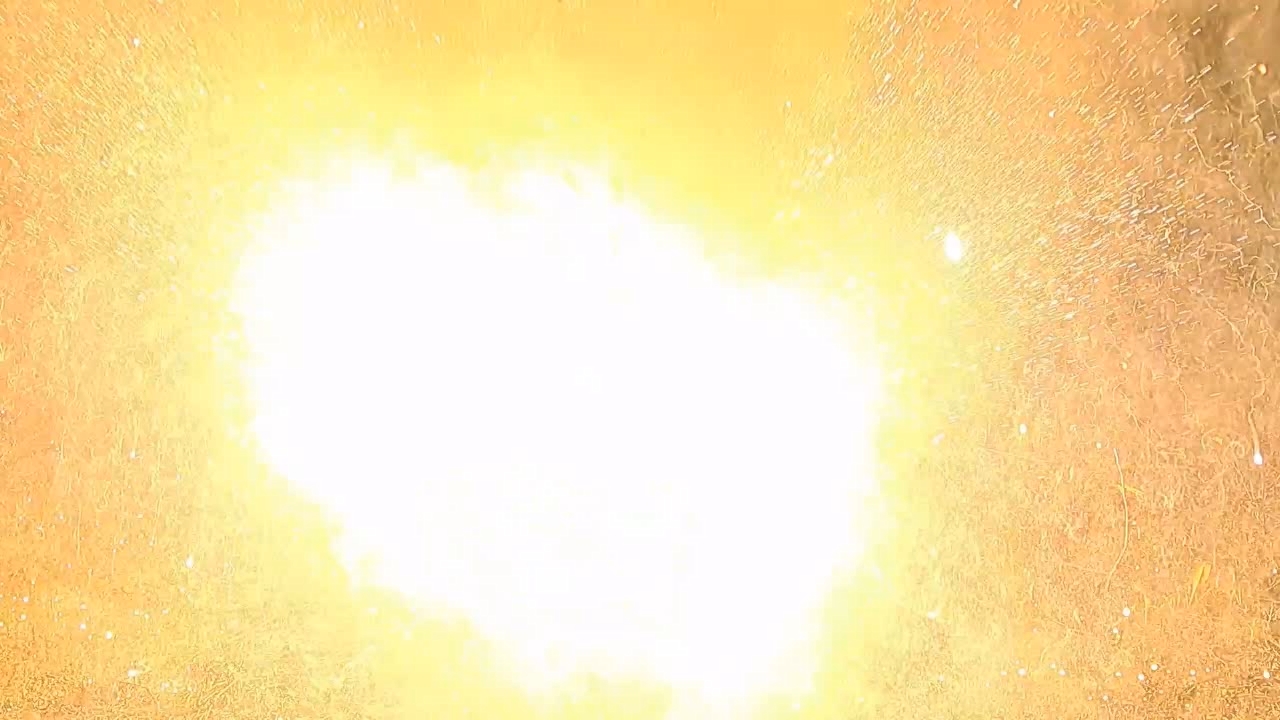

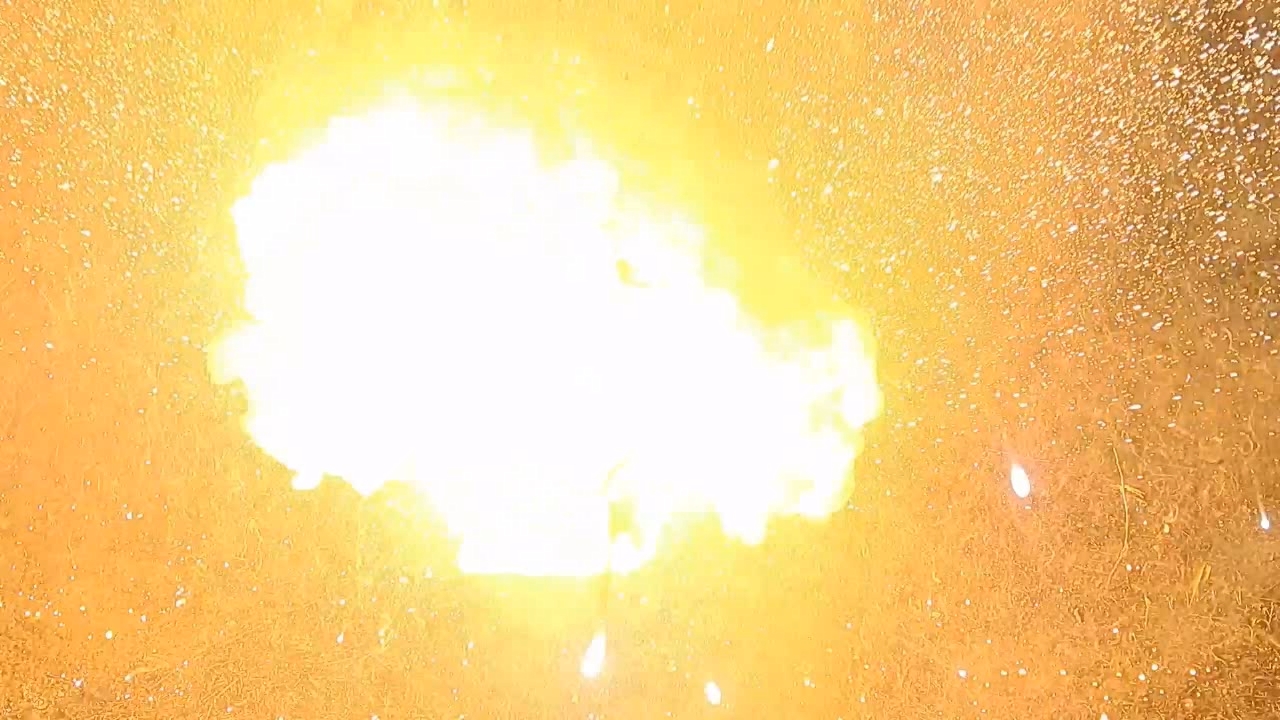

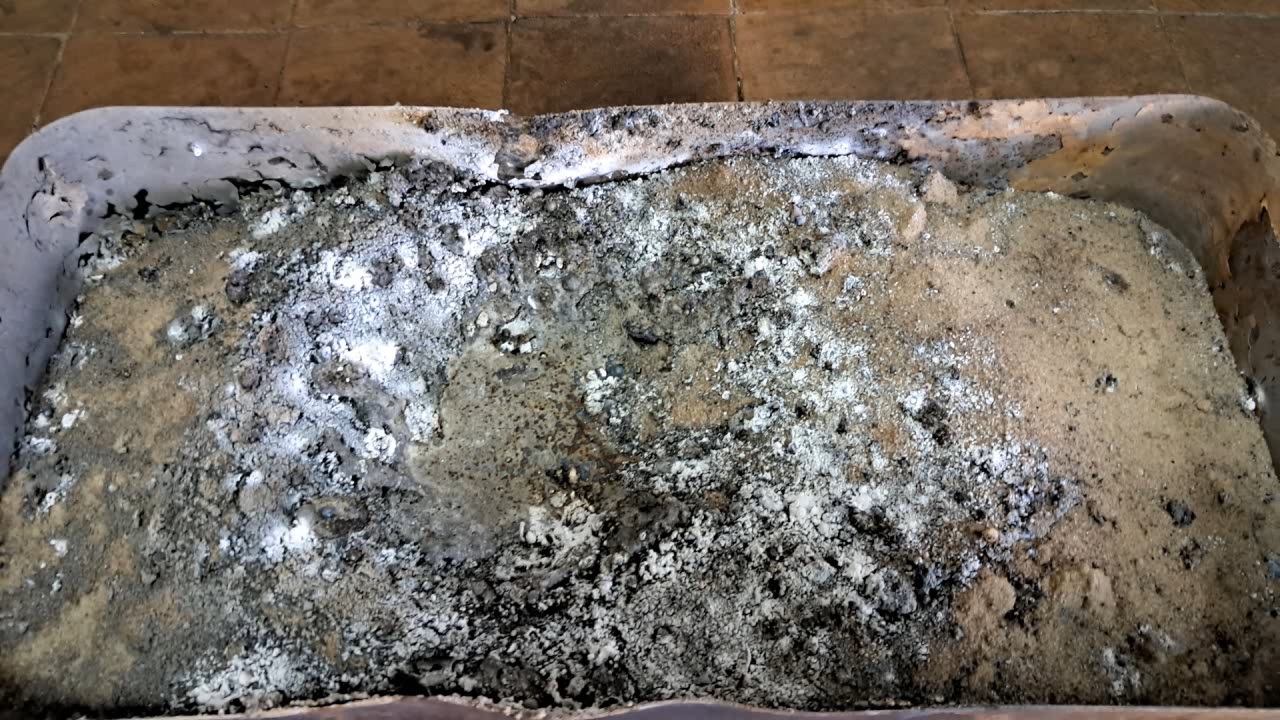

Горение термита: оксид железа (II, III)/алюминий/магний (Fe3O4/Al/Mg) - часть 30 Al - 100 g, Fe3O4 - 275 g, Mg - 40 g. However, I ended up reducing the amount of magnesium by a factor of four. The main reason was that the magnesium was in the form of fragments from cruise missile bodies (Elektron alloy). Crushing these fragments was extremely difficult - they had to be struck with a hammer on an anvil using full force. As a result, magnesium pieces flew all over the laboratory. One large fragment flew off after a strike and hit a one-liter glass bottle containing concentrated nitric acid. Miraculously, the bottle didn't break. Let me remind you: the idea was not just to add powdered magnesium to the Fe3O4/Al thermite, but to use magnesium in the form of separate layers made from large magnesium pieces. These layers were to alternate with layers of Fe3O4/Al thermite. The magnesium would be heated to its boiling point by the burning thermite, turning into vapor and causing the thermite to scatter due to the sharp increase in volume when a solid turns into gas. The magnesium vapor would then burn in the air, releasing additional energy. For the tested composition (Al - 100 g, Fe3O4 - 275 g, Mg - 10 g, see Part 27), this effect was weak, so I returned to the original idea: Al - 100 g, Fe3O4 - 275 g, Mg - 40 g. It took three days to crush the magnesium with a hammer. Of course, I didn't do this continuously — instead, I worked periodically: I struck the magnesium, collected the scattered pieces, and struck it again. When I got tired or bored, I switched to other tasks. Eventually, I obtained 40 g of magnesium in the form of irregularly shaped particles, ranging in size from fractions of a millimeter to about one centimeter. I weighed the aluminum (particle size: 100-140 microns) and iron(II,III) oxide, then mixed them thoroughly. Just then, a colleague arrived with an aluminum beer can. It was smaller than the cans I had used before. He suggested I use this particular can for the thermite. I poured a portion of the aluminum-iron oxide mixture into the bottom of the can and compacted it with a hammer. Then I added a layer of magnesium particles, followed by another layer of the aluminum-iron oxide mixture, and compacted it again. I repeated this process until I realized that the can was too small - there wasn't enough space for all the thermite and magnesium. Should I trust people after that? I transferred the mixture into a larger aluminum beer can, taking care not to let the layers loosen. I then added the remaining thermite and magnesium in the same layered fashion. The topmost layer was thermite. On top of that, I placed an incendiary mixture prepared from 2 g of finely powdered aluminum and 3 g of iron oxide. The thermite-filled can was then placed in an iron tray filled with dry sand (I had formed a shallow depression in the sand around the can). The prepared thermite stood in my lab for two days. Unheard of! Previously, I always tested thermite immediately after preparation, but this time I had urgent work. Finally, I found some free time. I began to wonder: should I invite a colleague to help with the test? On the one hand, he had a second phone to film the experiment, and I would definitely need assistance. Also, he might find the experiment interesting. On the other hand, I didn't want to bother him - I knew for certain that he was busy at the time. In the end, I invited him anyway. He agreed, and then asked: - Will you conduct the experiment here? [In the lab] - No, of course not - otherwise, the lab will burn down! We went out into the yard. I carried a tray with the thermite, a gas burner, and a protective shield. My colleague brought two tripods for smartphones. We set up in a secluded area where strangers wouldn't be able to see the experiment. I placed the tray with thermite on the ground and set up the two tripods. I positioned my phone closer to the thermite, and my colleague's phone farther away, since I expected burning fragments to fly off. Before the test, I was very nervous - I worried that the experiment might fail and all the effort would be wasted. I was eager to begin. Just then, my colleague stopped me, brought over a large sheet of slate, and placed it to the right of the thermite to hide some unsightly background objects. In response, I expressed - in not a very polite manner- what I thought about that piece of slate and his concern for aesthetics. I aimed the flame of the gas burner at the incendiary mixture and quickly stepped back. The mixture caught fire, and then the thermite ignited. A bright white flame burst from the can with a hiss, sending out smoke and a shower of sparks. And then, the experiment took an unexpected turn - a small explosion occurred, accompanied by a brilliant flash. The explosion scattered large chunks of burning thermite in all directions. This was followed by several more explosions and intense flashes, resulting in showers of glowing sparks. After the reaction, a yellow-hot area remained in the tray. I assumed it were molten reaction products. I picked up the secondary camera to film the results of the combustion at close range. While filming, I nearly stepped on a large, still-hot fragment of the reaction products - I had to watch my footing very carefully. It turned out that after the combustion had finished, there wasn't a drop of molten material left in the sand tray - only hot sand and ''spots'' of magnesium oxide remained. The entire reaction mixture had been blown away by the explosions! While I was filming, I heard strange sounds behind me and turned around... Fire! Behind me was a shed filled with old fluorescent lamps, worn-out furniture, plastic lamp covers, and other items. Its walls were made of wire mesh. The shed was engulfed in flames! The distance from the thermite to the mesh wall was about 2 meters, and to some ignition sources - around 3 meters. I put my smartphone on the ground and shouted to my colleague: - Fire! I grabbed a 50-liter barrel full of rainwater and began pouring it onto the fire through the wire mesh. My colleague shouted: - Don't pour out all the water! Not all of it! He planned to enter the shed and pour water on the fire from the inside. However, I was convinced the shed door was locked, so I poured nearly the entire barrel through the mesh. The fire weakened, but it didn't go out. At that moment, my colleague discovered there was no lock on the door at all. The shed was secured only with a piece of wire - there was nothing valuable inside. Burnt-out lamps and broken furniture weren't exactly theft-worthy. He climbed into the shed and threw out a large piece of burning foam rubber. I extinguished it with the remaining water. The visible flames were out, but smoldering and burning continued under piles of long fluorescent lamps. The glass tubes, which contained mercury, began cracking loudly - some from the heat of the fire, others from the sudden cooling caused by the water. I asked my colleague to fetch a bucket of water. Then I climbed into the shed and started moving the lamps aside to clear access to the fire. Frightened neighbors came running after seeing the smoke. I reassured them that everything was fine, the fire was under control, and we were extinguishing it. My colleague collected water not from his lab, but from a nearby workshop - it was closer. He entered the shed and poured water onto the fire. But it wasn't enough - bucket after bucket was needed. Soon, the workshop staff arrived along with my colleague. One of them began to grumble: - We've got paints and flammable solvents in here - gasoline, acetone, white spirit. There's cardboard and old furniture too. It was a bad idea to burn thermite here... But there was no argument: I had no time to debate, and they had no desire to quarrel. Instead, they brought a hose connected to the water supply. Although the hose didn't reach all the way to the shed, it served as a closer source for filling buckets than the distant tap. We filled buckets with water, carried them into the shed, and poured the water over anything still burning or likely to ignite. By then, no flames were visible, but white smoke billowed from under the pile of fluorescent lamps. The lamps, fittings, and old boxes made it difficult for the water to reach the smoldering material. Several times, the smoke formation seemed to stop - but then resumed. My colleague and I ended up using around twenty buckets of water (about 20 liters each). Only after that did the emission of smoke stop, and it began to dissipate. I stayed after work, checking on the shed periodically to ensure the fire didn't reignite. The workshop staff said half an hour would be enough, but I stayed for a full hour. There was no more smoke or any sign of fire. Finally, I calmed down and went home. But once home, a frightening thought struck me: - What if those fluorescent lamps weren't burnt out - but were new? I had broken at least two of them with my feet while maneuvering through the cluttered shed, trying to pour water in the right places. An unknown number cracked due to heat and sudden cooling from contact with cold water. The next day, my colleague reassured me that all the lamps were burnt out - if they had been new, the shed would have been securely locked. What conclusions can be drawn? It's a good thing I invited my colleague - extinguishing the fire alone would have been extremely difficult. But my biggest mistake was not bringing a fire extinguisher. In earlier tests, I always had a carbon dioxide fire extinguisher nearby. Yet during the last few experiments, I had started conducting them without one. I also recalled how, before filming, my colleague placed a slate sheet on the side to "improve the view." I had reacted rather rudely, telling him not to fuss. While we were putting out the fire, I admitted that he had been right - but unfortunately, he had placed the slate sheet on the wrong side, opposite the shed. The next day, the story took an unpleasant turn. I had synthesized a small amount of picric acid (for experiments with deuterium and tritium water), filtered the product, and placed it on filter paper to dry. I bent over to transfer the remaining crystals from the filter to the paper. Suddenly, a large dark red stain appeared on the white paper containing pale yellow crystals. Then a second stain appeared on the nearby tablecloth. Only then did I realize I was bleeding - apparently, I had injured the top of my head while putting out the shed fire, and hadn't noticed it for an entire day. |

Combustion of Thermite: Iron(II, III) Oxide/Aluminum/Magnesium (Fe3O4/Al/Mg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In this photo, the magnesium weighs 40 g, and the rest is a disposable cup |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|