Chemistry and Chemists № 2 2025

Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts

| Content | Chemistry experiments - video | Physics experiments - video | Home Page - Chemistry and Chemists |

|

Chemistry and Chemists № 2 2025 Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts |

Experiments with Thermite - pt.19, 20, 21 Chemist |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

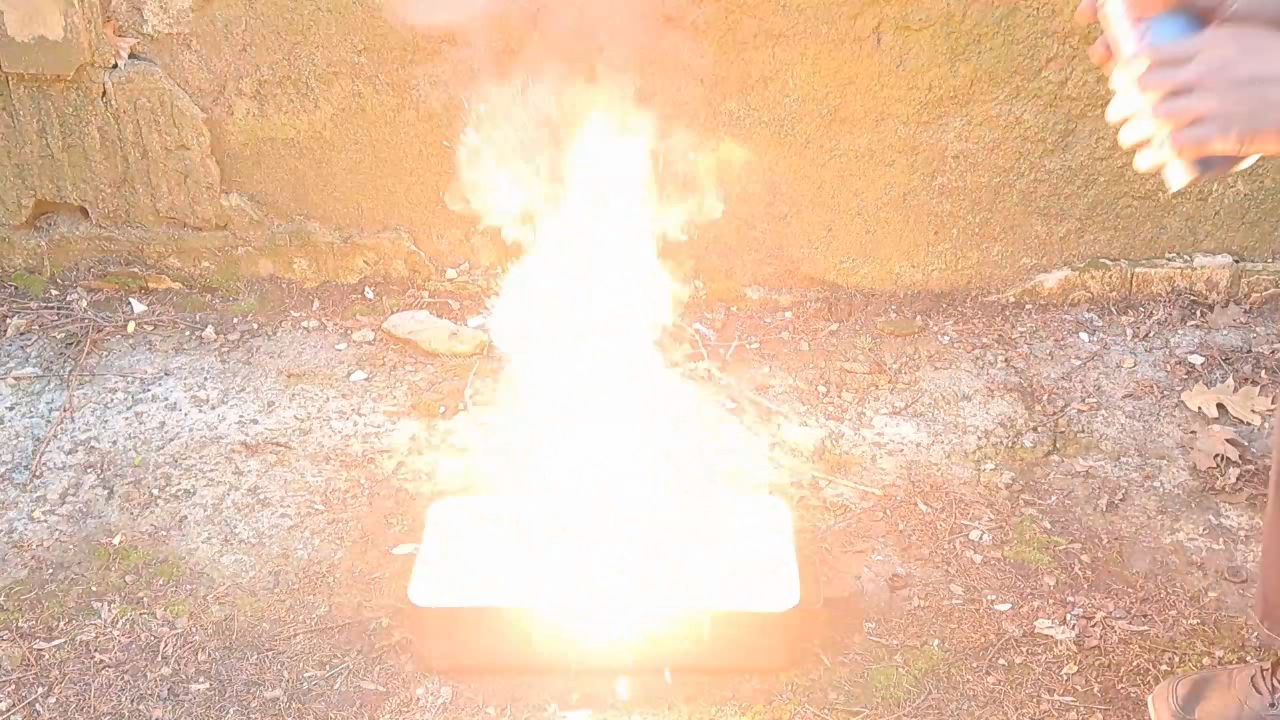

Briquette Made of Thermite: Iron(II, III) Oxide/Aluminum (Failed Experiment) - Part 19

In some experiments, I used heat-resistant containers (tin cans and clay pots) for thermite combustion; in others, the thermite was placed inside a shell that easily burned during the reaction (such as a paper bag, aluminum foil, or an aluminum can). An idea arose to try this experiment without using containers or shells at all, by pressing the thermite into a cylindrical briquette. This required a mechanical press (for example, a hydraulic one), which the lab did not have.

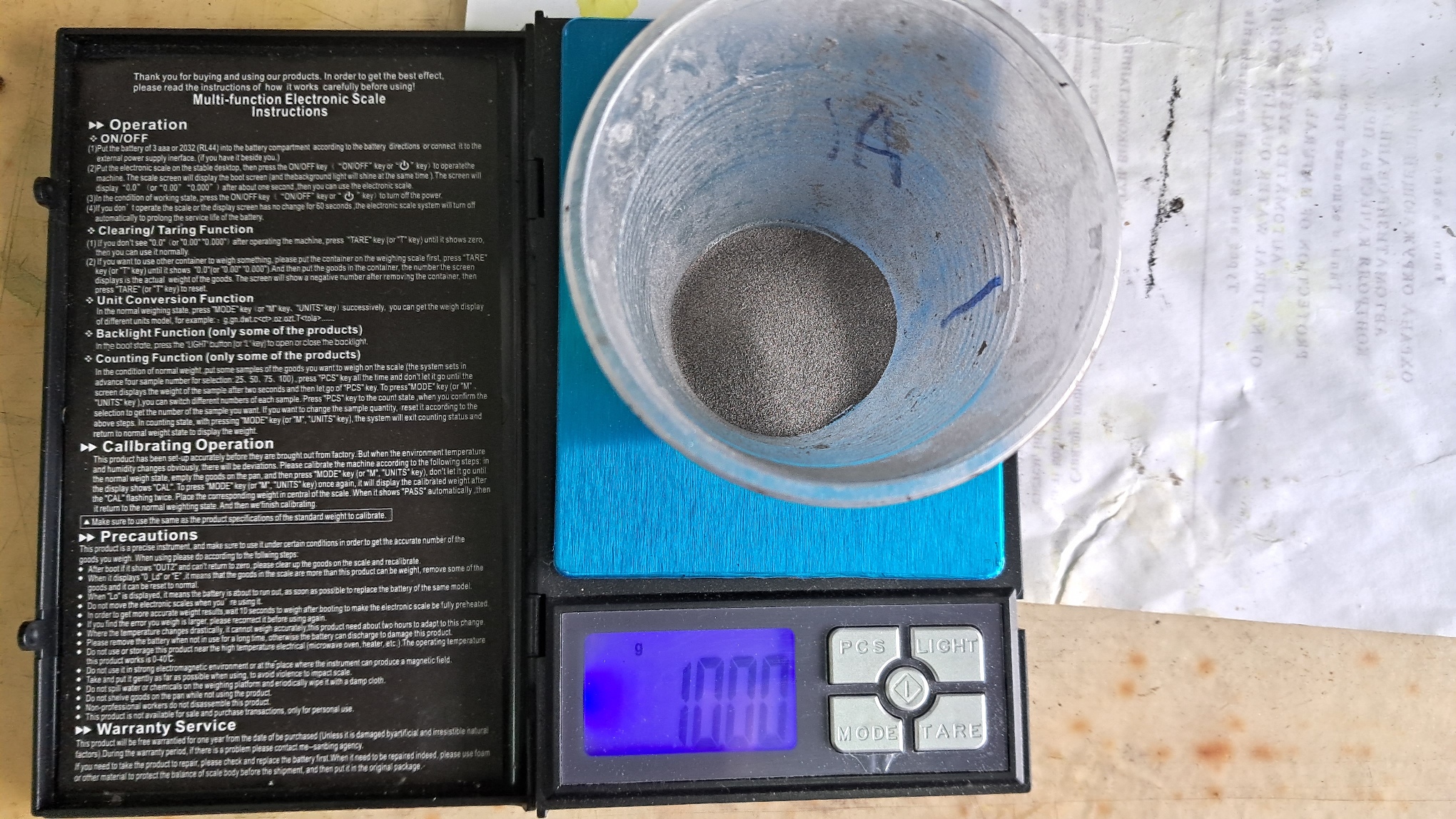

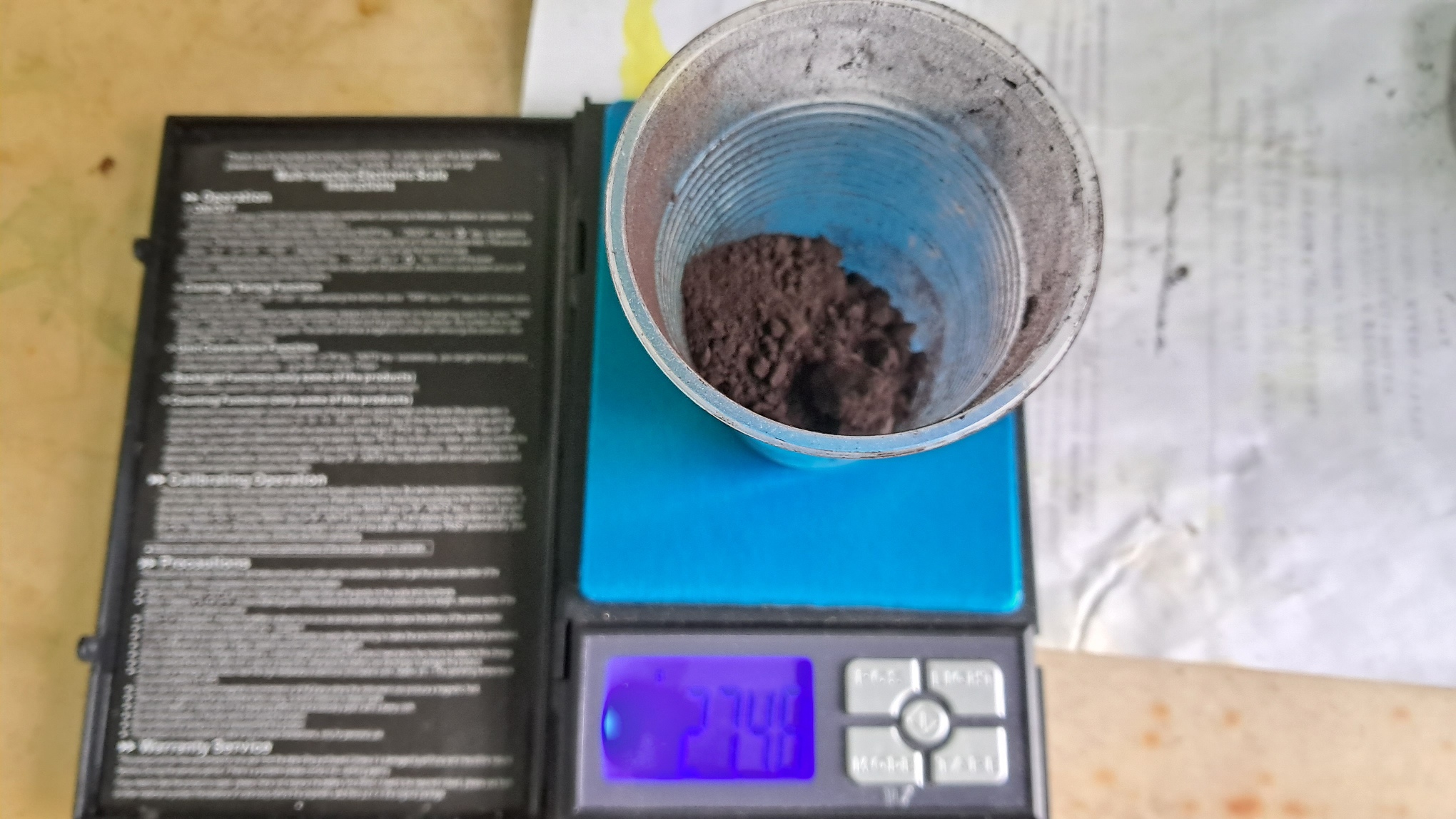

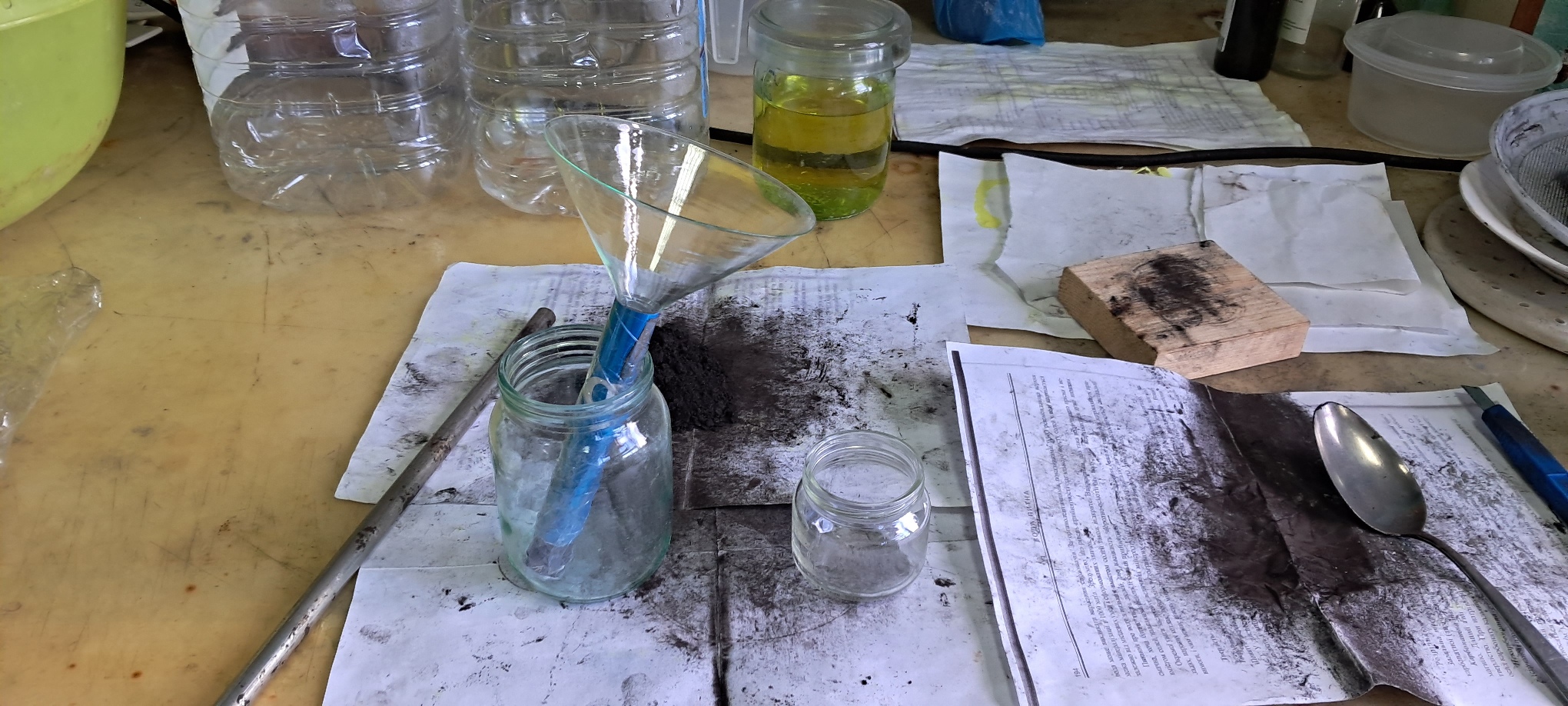

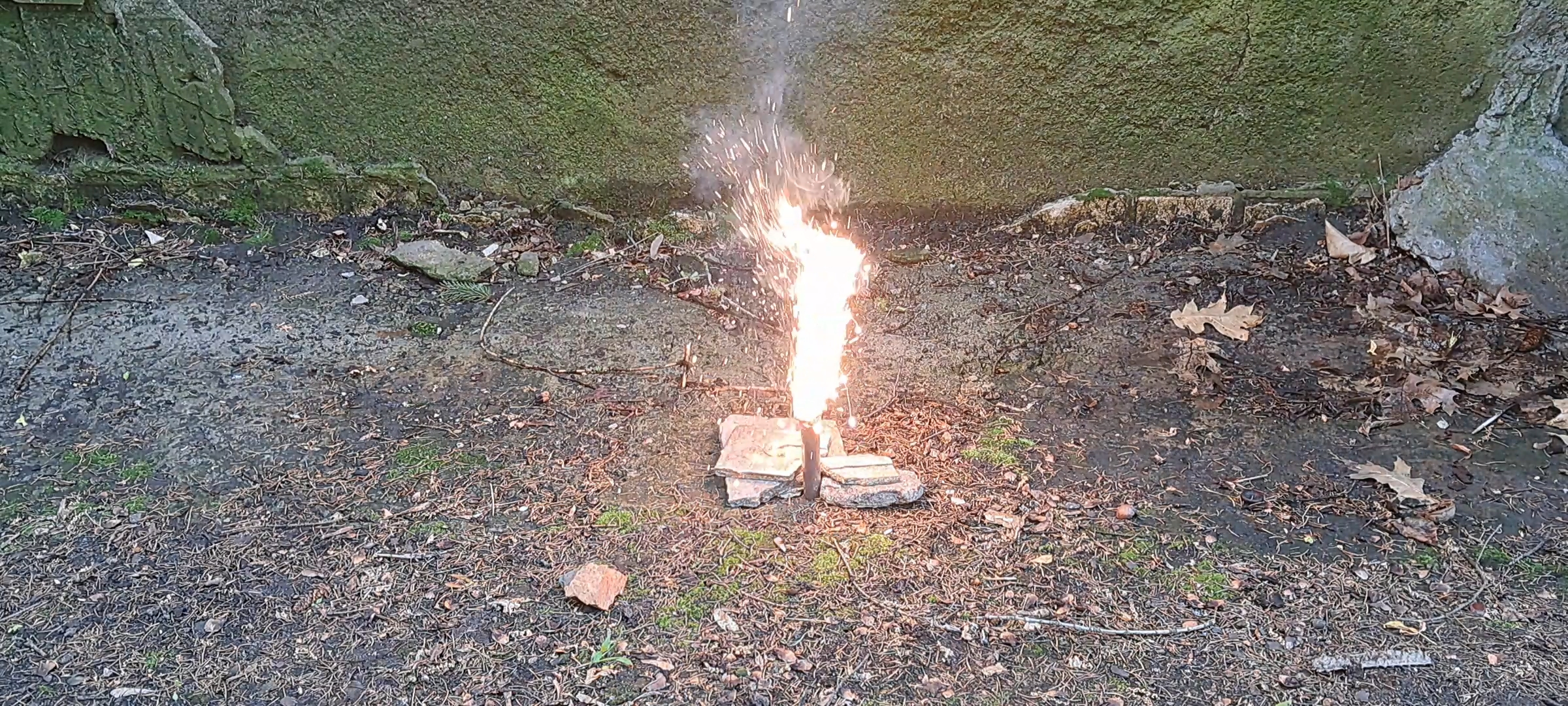

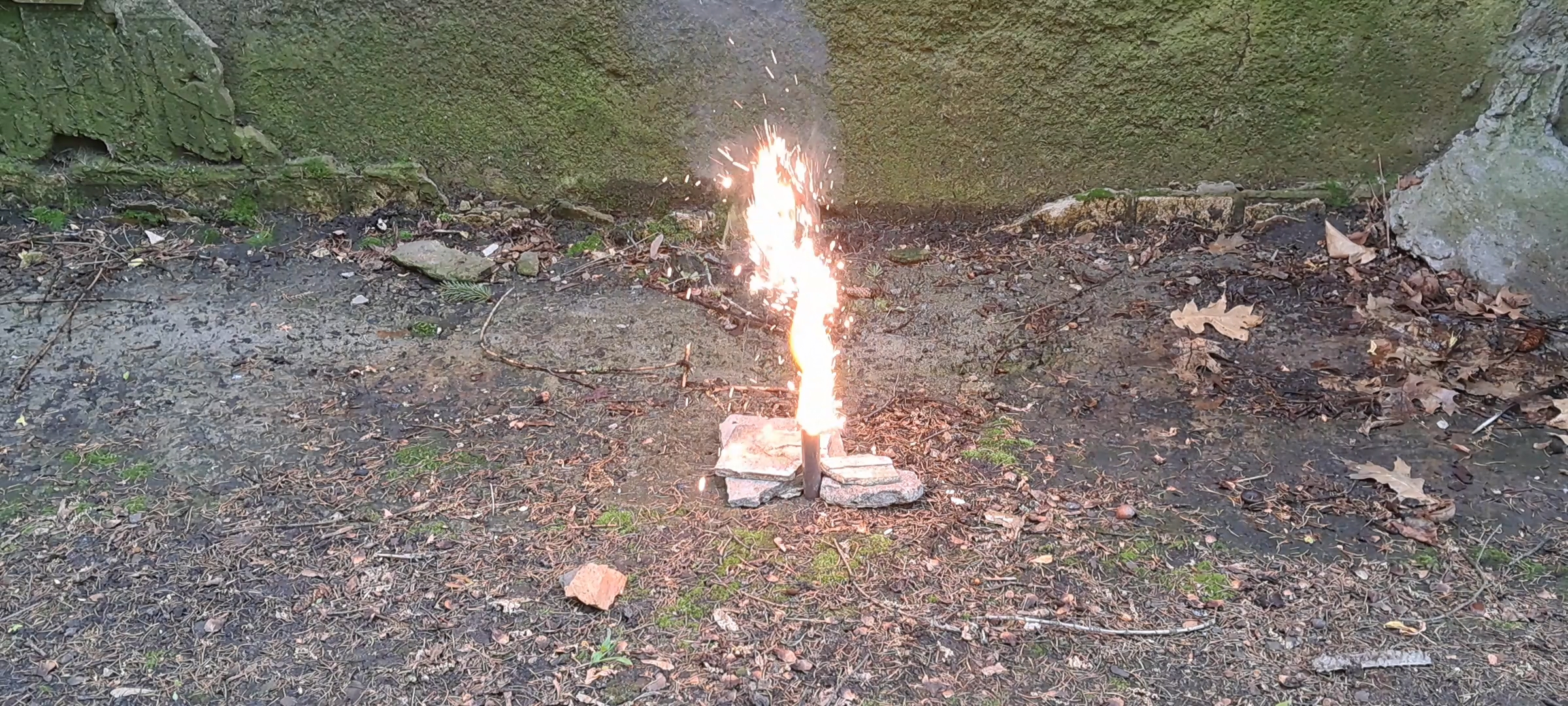

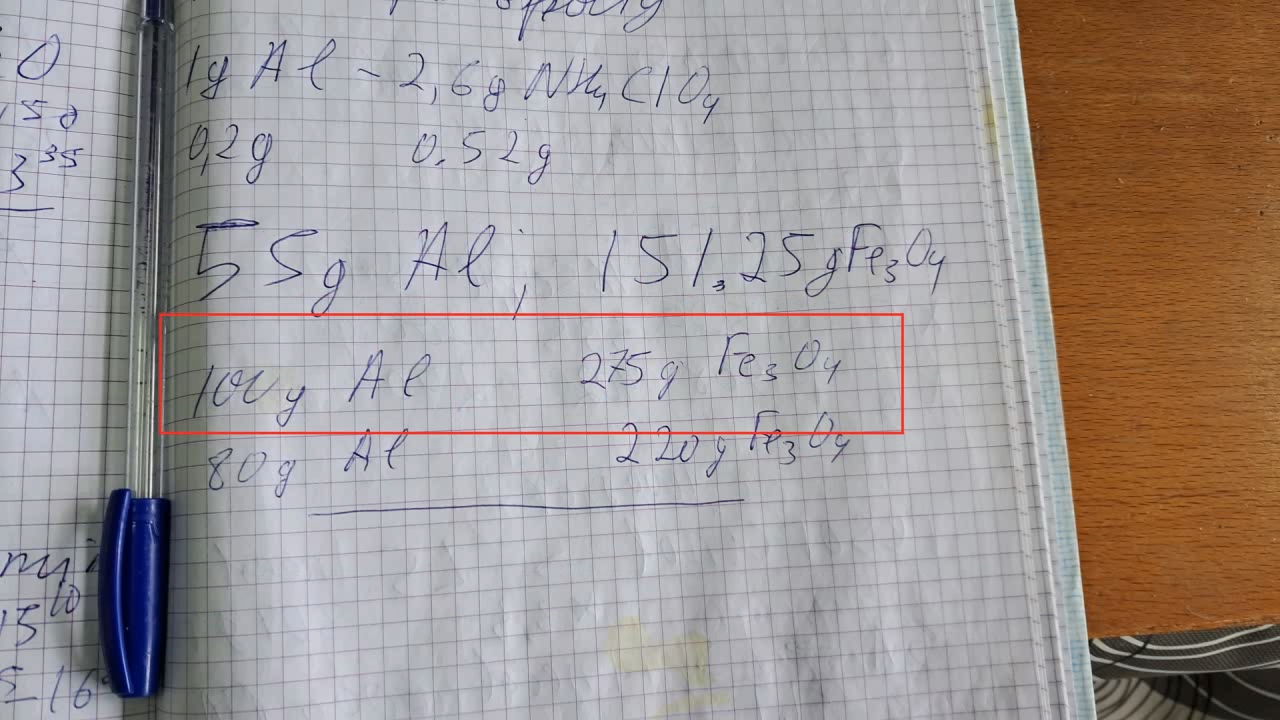

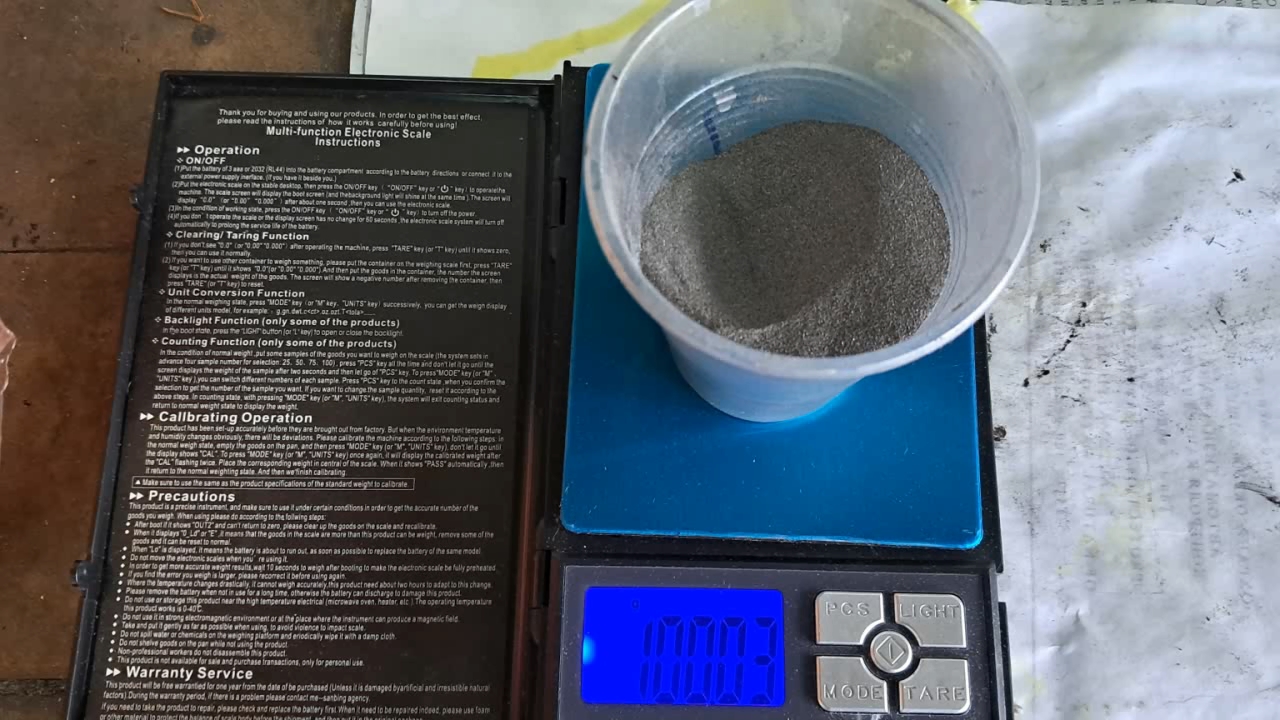

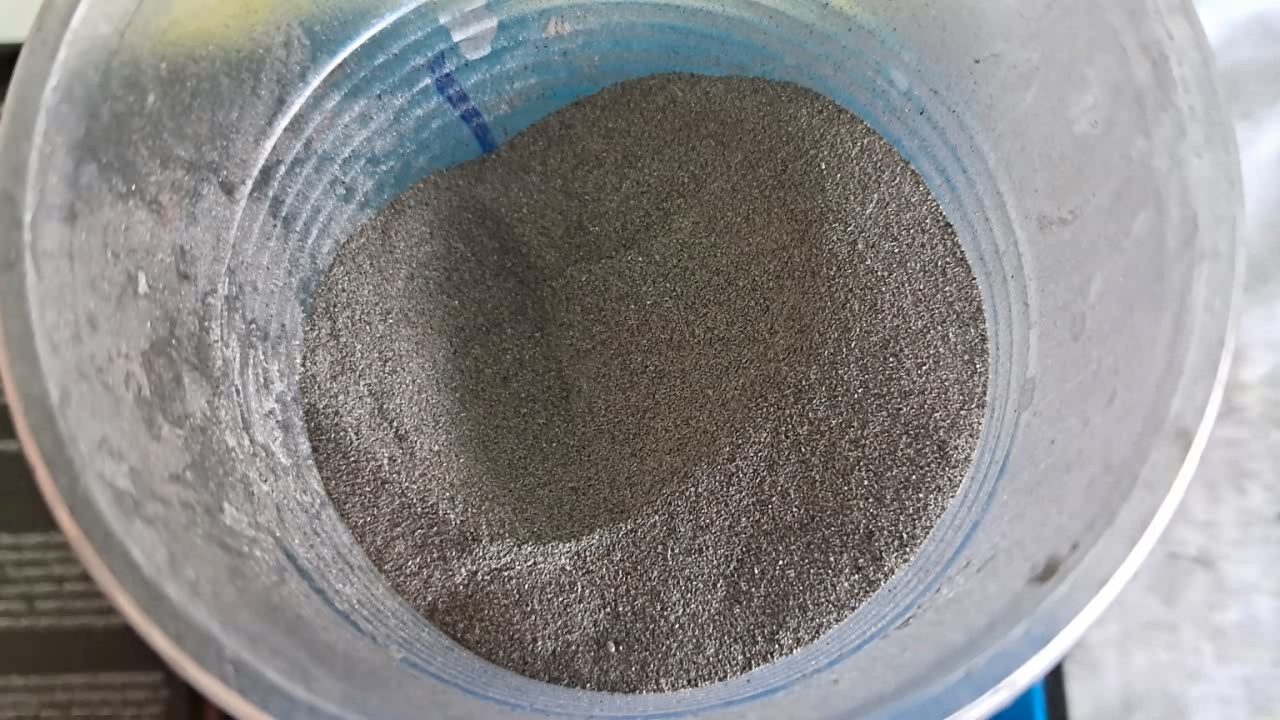

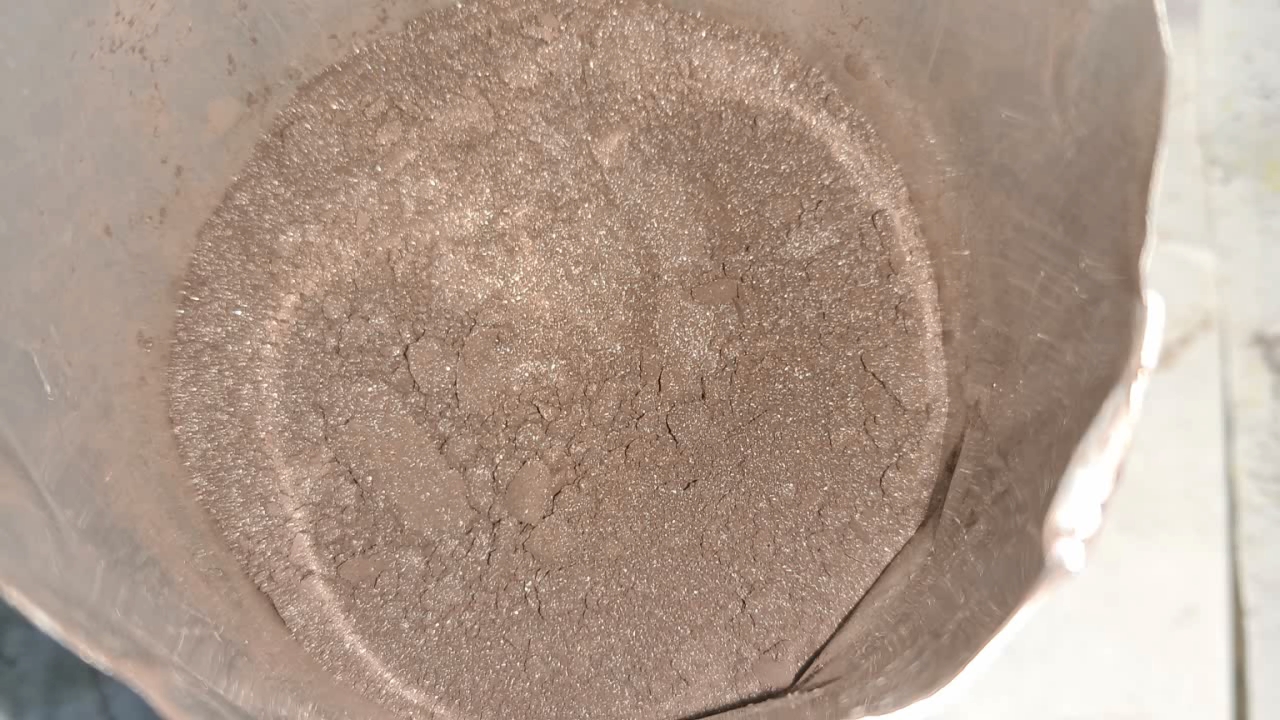

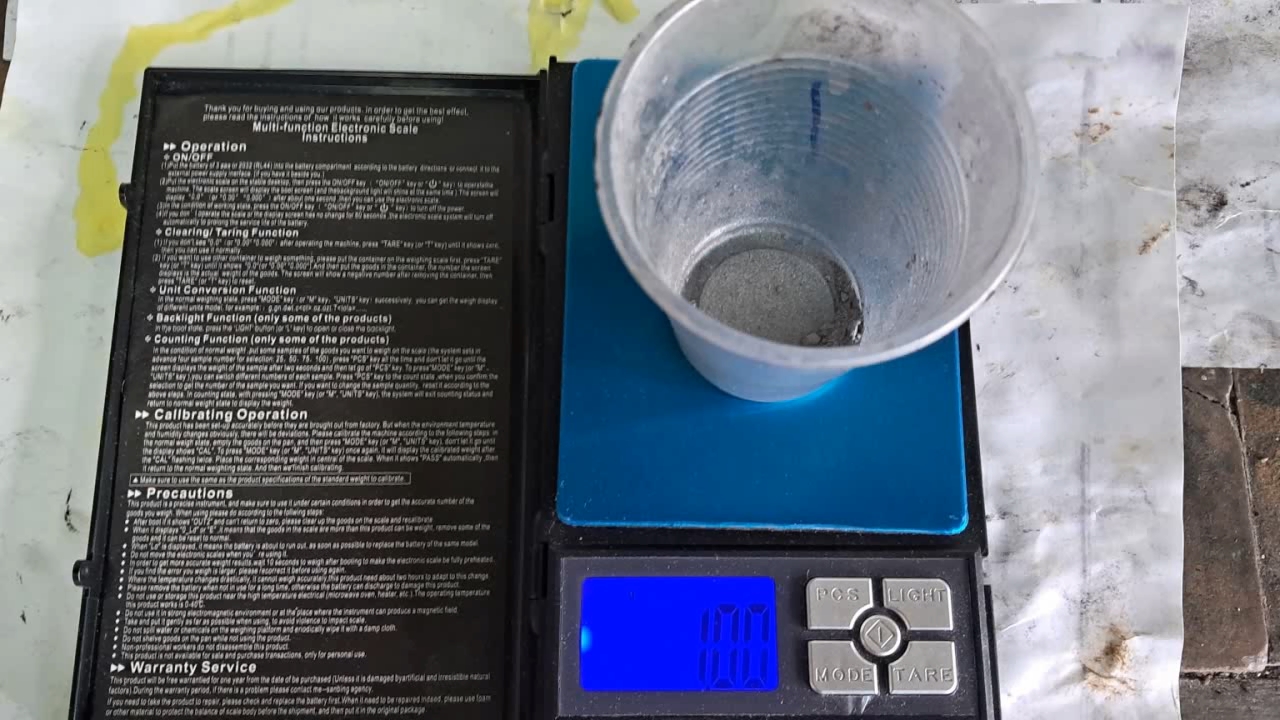

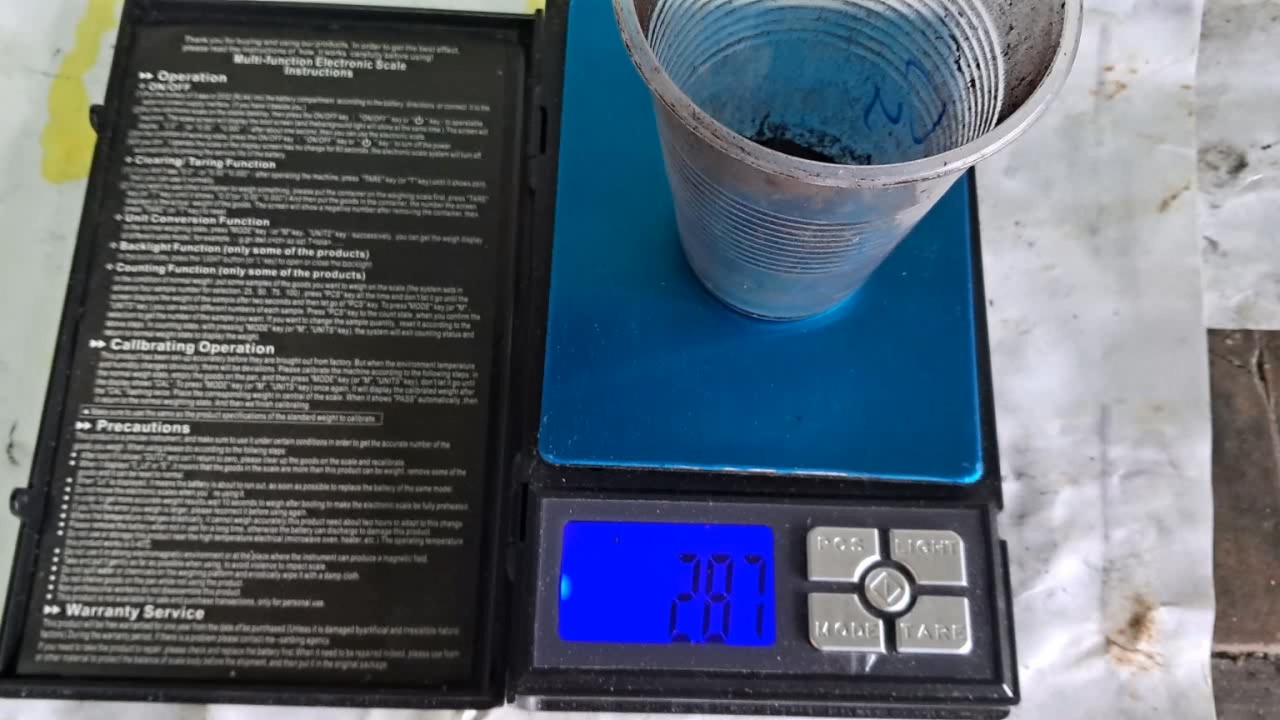

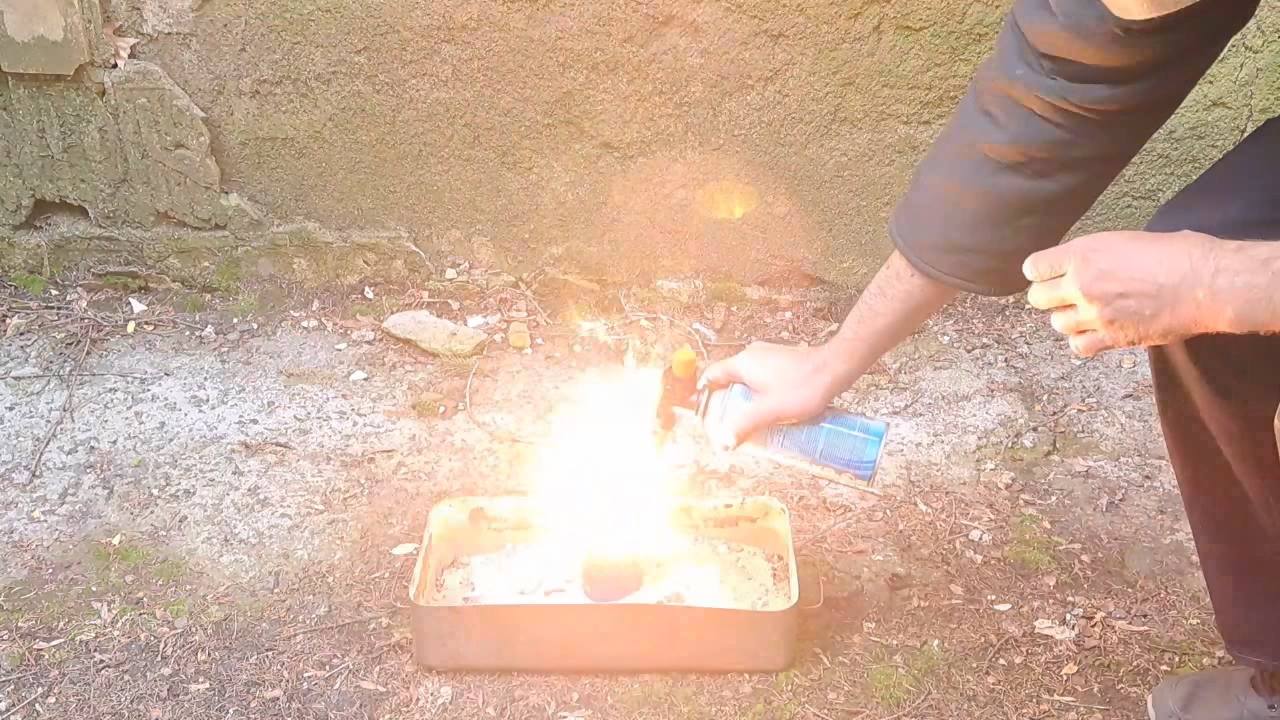

Брикет из термита: оксид железа (II, III)/алюминий (неудачный эксперимент) - часть 19 I decided to try a simple, though not entirely reliable, method. I cut a rectangular sheet from a beer can, rolled it into a cylinder about 2.5 cm in diameter, and tightly wrapped it with tape. I also sealed the bottom hole with tape. My plan was to pour small portions of thermite into the cylinder, compress them using blows from an iron rod, add more thermite, compress again, and so on. Finally, I would cut the tape, unroll the aluminum sheet, and remove the compressed briquette. To improve the mechanical properties of the powders and make pressing easier, a binder is often added. According to the literature, small amounts of castor oil, mineral oil, drying oil, acrylic polymers, rubber, or similar additives can be used in thermites. I decided to use a small amount of polystyrene dissolved in acetone for this purpose. I prepared a mixture of 10 g of aluminum powder (100-140 microns) and 27.5 g of iron oxide (Fe3O4), and added a few drops of polystyrene solution (made from foam plastic) in acetone. The solution turned out to be too thick and formed lumps. After mixing, I pressed the thermite into a cylinder as described above. I placed it in a thermostat to remove the solvent. After drying, it turned out that the briquette was not mechanically strong—it crumbled when squeezed in the palm of my hand. I crushed the thermite, added 2 g of petroleum jelly (Vaseline), and pressed the powder into a briquette again. The new briquette was also fragile. Some sources recommended using liquid glass (an aqueous solution of sodium silicate) as a binder for thermite in amounts of a few percent. However, I assumed such thermite would be difficult to ignite, so I abandoned the idea of using thermite without a casing. I crushed the thermite once more and pressed it into a polypropylene test tube, hoping that the polypropylene would easily burn during the thermite reaction. On top of the pressed thermite, I poured an incendiary mixture consisting of 1 g of fine aluminum and 2.75 g of iron oxide (Fe3O4). I directed a strong burner flame at the incendiary mixture. The thermite ignited, producing a fountain of flame and sparks. However, after a few seconds, the combustion of the thermite was replaced by the combustion of the polypropylene—the thermite went out. Further attempts to ignite the thermite directly with a strong burner flame were unsuccessful (an incendiary mixture was required). This reminded me of a popular video about thermite, where a strong burner flame was directed into a bucket of thermite. Even though the surface heated to 800°C, the mixture did not ignite. Thus, the excess of organic binders and the polypropylene shell caused the burning thermite to go out, and it could not be ignited with a burner alone. The energy of the thermite was consumed by melting and decomposing the organic materials, and as a result, the heat released was not sufficient to sustain the thermite reaction. I noticed that some thermite mixtures containing organic binders also included additional oxidizers, such as sodium, potassium, strontium, or barium nitrates. These oxidizers react with the organic substances, releasing extra energy. I decided not to explore this topic further. |

Briquette Made of Thermite: Iron(II, III) Oxide/Aluminum (Failed Experiment) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The reagents and labware stocks |

|

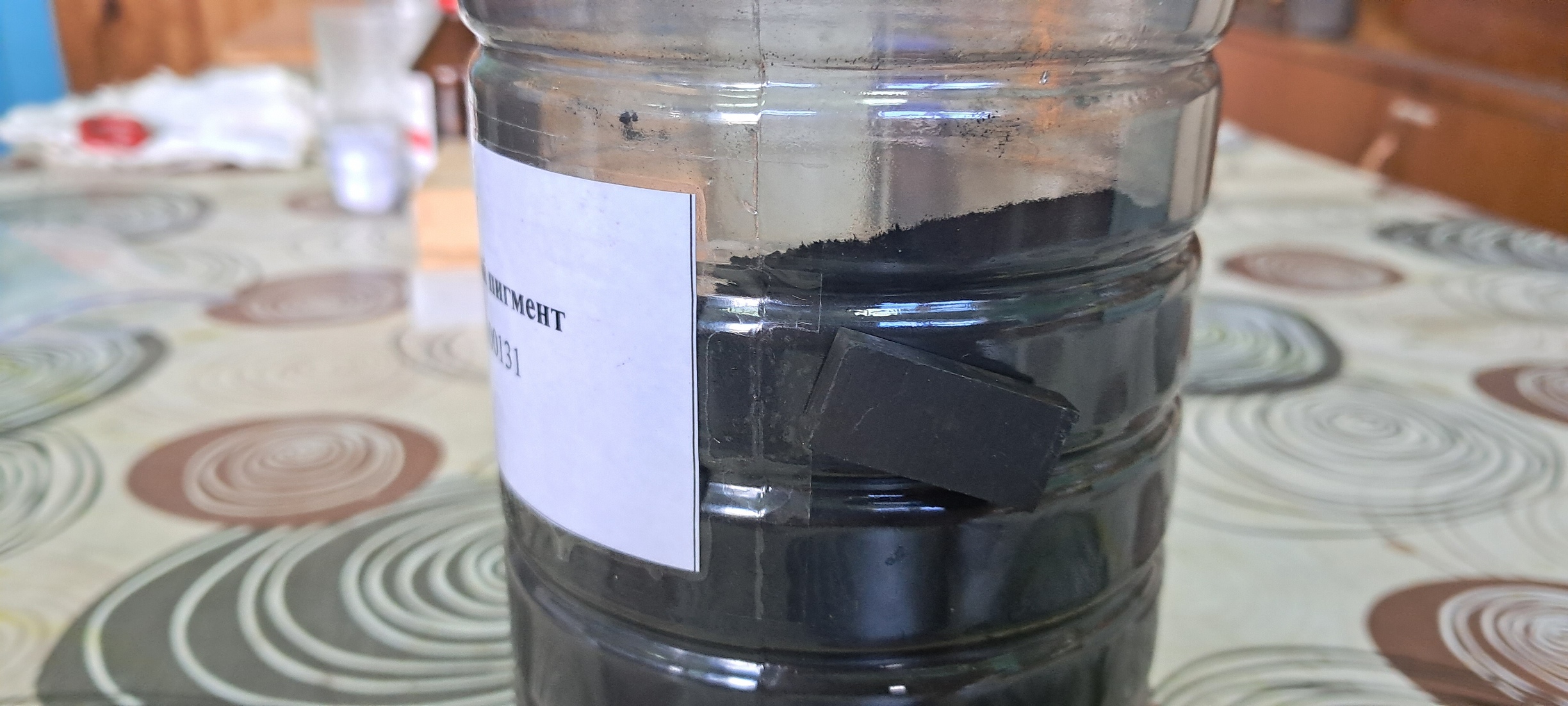

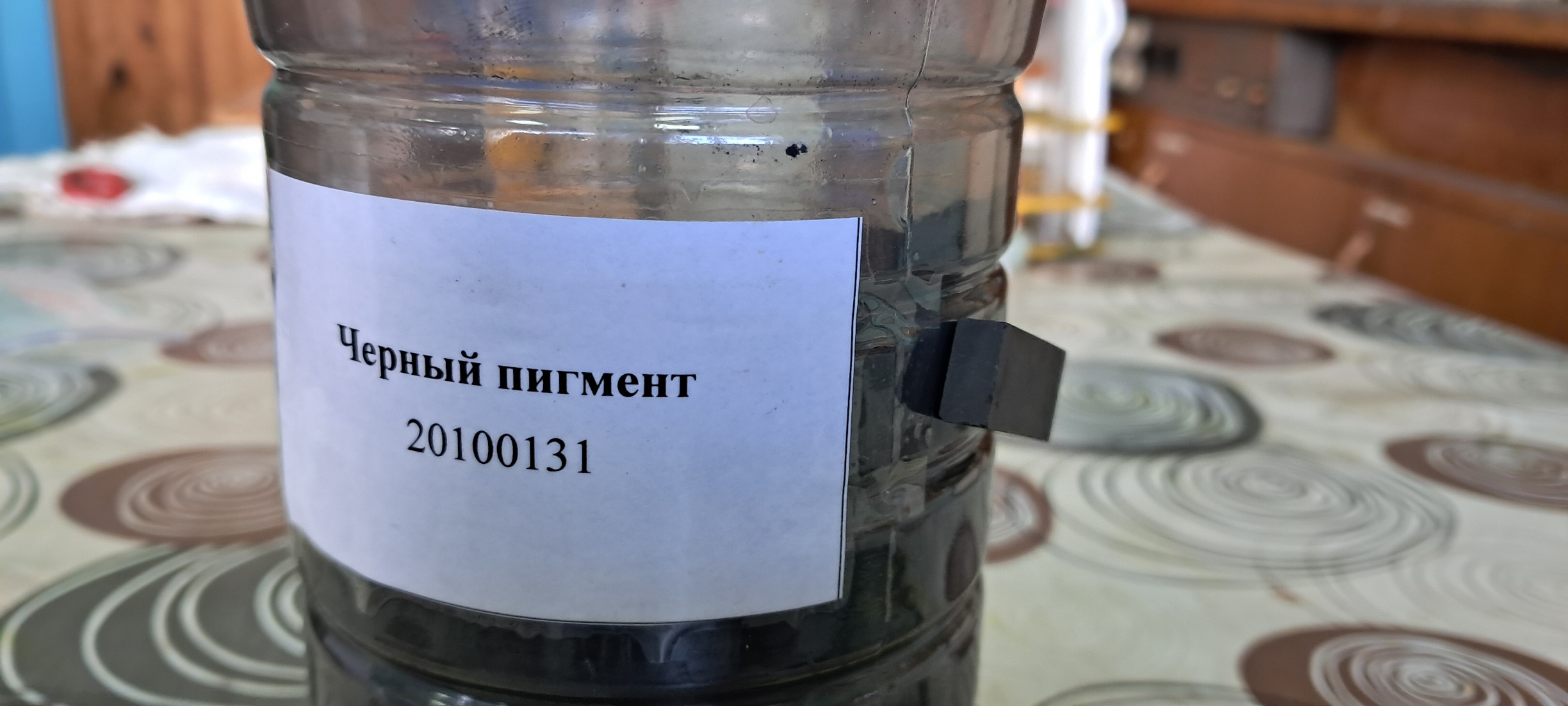

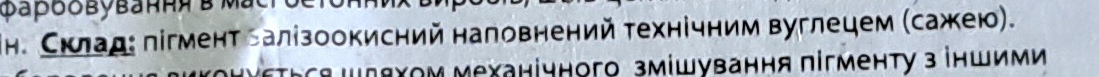

The new pigment |

The new pigment and a magnet |

|

The new pigment |

The pigment I have used |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

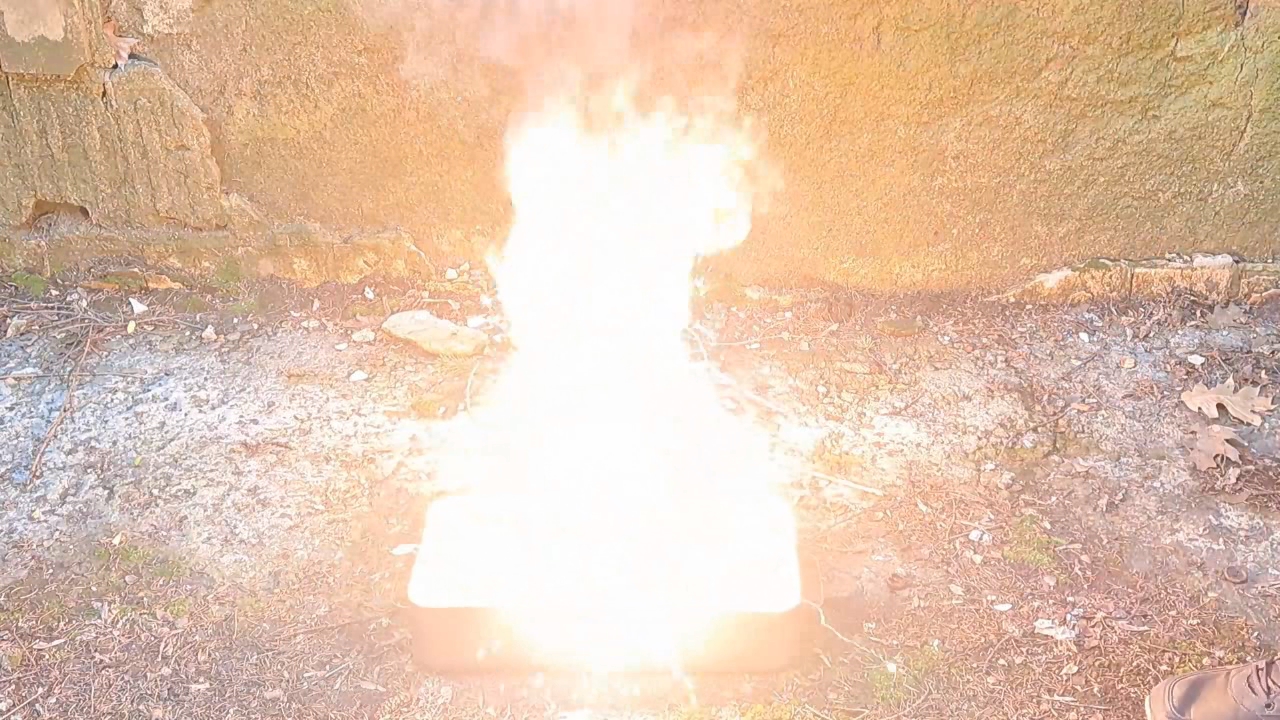

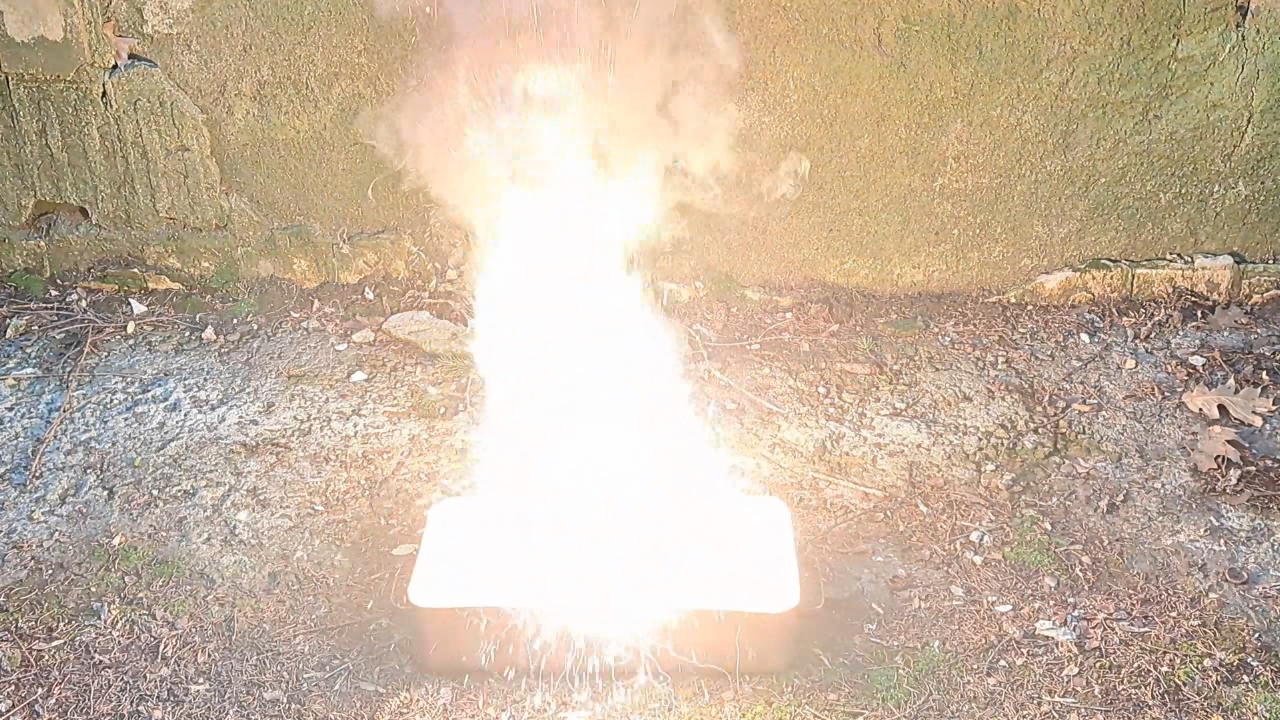

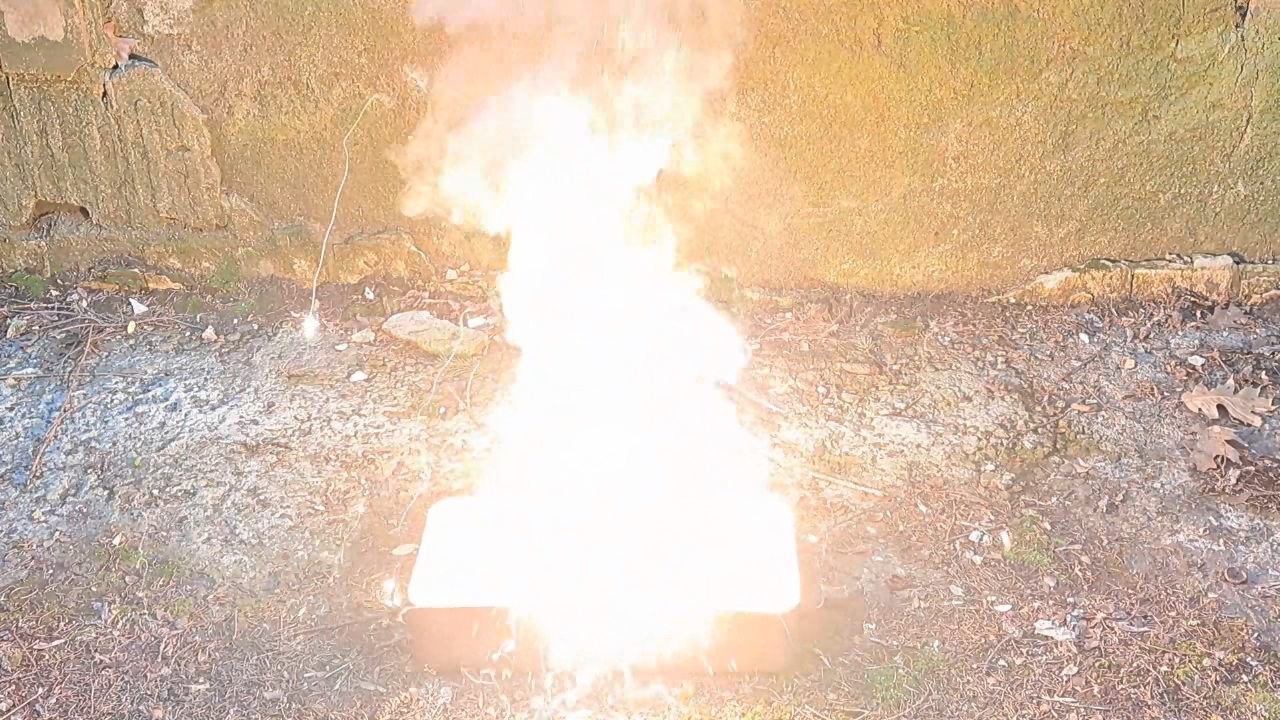

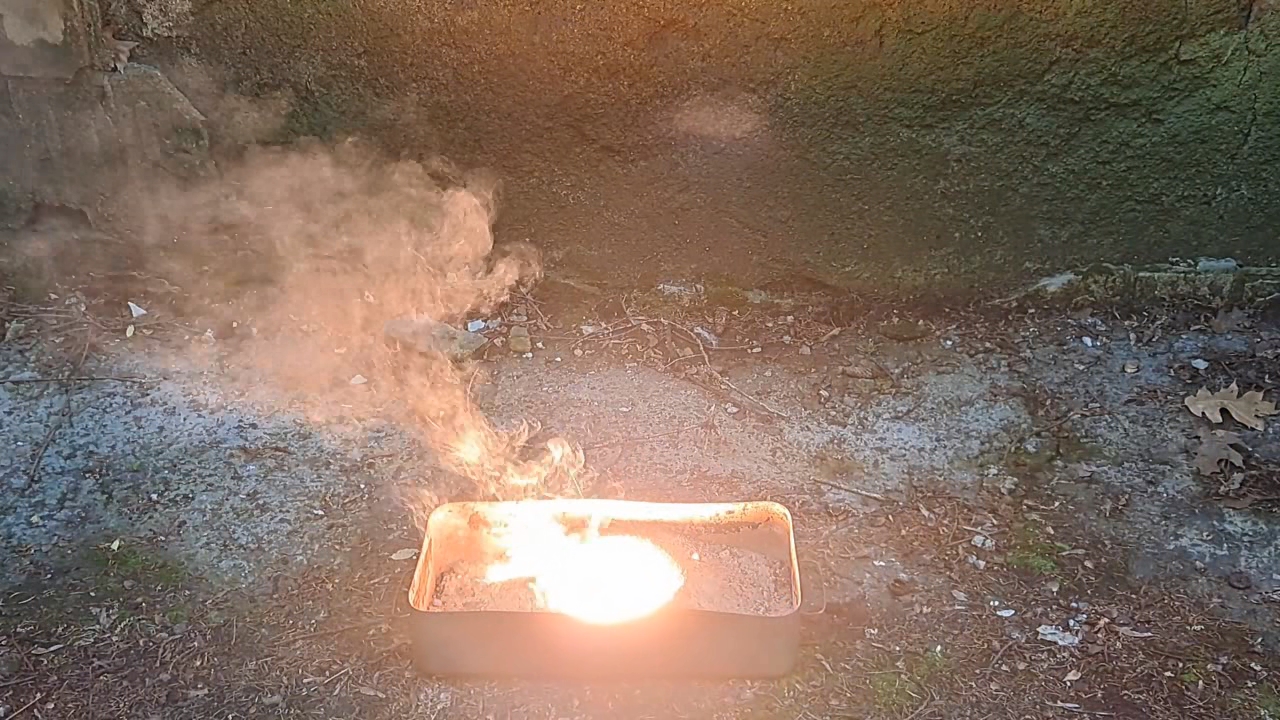

Combustion of Thermite: Iron(II, III) Oxide/Aluminum (Fe3O4/Al) - Part 21

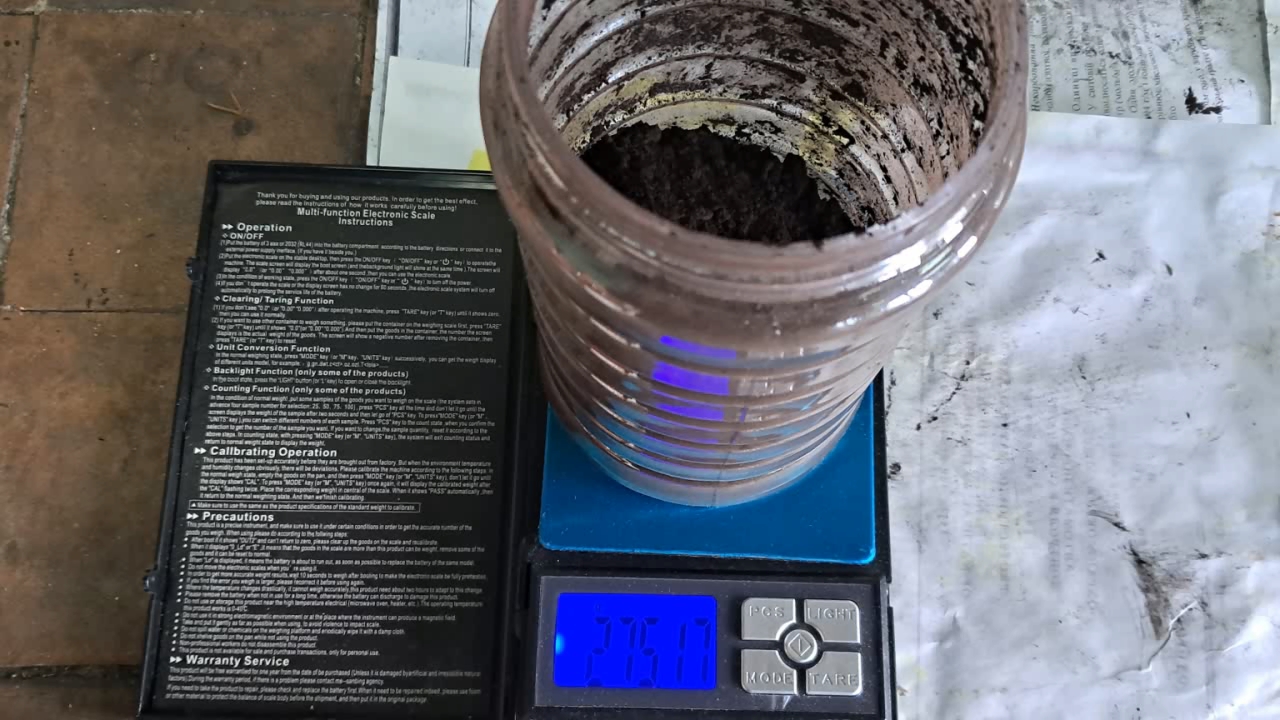

I prepared a mixture of 100 g of aluminum and 275 g of iron oxide (Fe3O4). The aluminum particles were 100-140 microns in size. I carefully pressed the mixture into an aluminum beer can using a hammer. On top, I poured an incendiary mixture consisting of 1 g of finely dispersed aluminum and 2.75 g of iron oxide.

Горение термита: оксид железа (II, III)/алюминий (Al/Fe3O4) - часть 21 This experiment was almost identical to the previous thermite experiment described in Part 18. However, I made a few small changes. First, I did not add sulfur to the thermite. Second, I used iron oxide with added soot to prepare the incendiary mixture. I had recently found a jar of this oxide (see Part 20 of the article), and I wanted to test whether the addition of soot interferes with the combustion of the iron oxide-aluminum mixture. If the soot had posed a problem, the incendiary mixture could easily have been replaced with one based on high-quality iron oxide. Finally, this time I placed the smartphone closer, accepting the risk of it being damaged by the burning thermite. I aimed the burner flame at the incendiary mixture. It flared up, then the thermite ignited. The flame was bright and extremely hot. Sparks flew in all directions, and a lot of gray smoke was produced. The sight of the furious burning was frightening. Watching the thermite reaction, I realized that if I had conducted this experiment in the lab, the flame would certainly have gotten out of control. The combustion lasted about 10 seconds, leaving behind a "lake" of molten iron and aluminum oxide. A colleague motioned for me to pick up the camera and film the melt from close range—so I did. As I approached the yellow-hot mass, I felt intense heat. At that moment, I thought: "Will the infrared radiation damage the smartphone?" The heat and smoke made me feel dizzy. The smoke interfered with the camera's ability to focus, but I continued filming. A few seconds later, I discovered… that the camera was off. When I took it off the tripod, I had accidentally pressed the stop recording button. This had happened during one of the previous experiments—interesting footage was lost. This time, however, the reaction products cooled slowly, so the lost shots were not critical. I turned the camera back on and filmed the molten "lake," which gradually cooled and solidified. A little later, I turned it over with a stick—the solidified reaction products had formed an ingot shaped like a one-sided convex lens. The sand beneath this "lens" glowed red. I asked a colleague to press the "lens" with a stick to squeeze any remaining melt from its core. However, by this time, the entire mass had solidified. During the cooling process, it cracked. Sharp, hot fragments, dangerous to the eyes, flew off. I did not remove my protective mask the entire time. |

Combustion of Thermite: Iron(II, III) Oxide/Aluminum (Fe3O4/Al) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|