Chemistry and Chemists № 2 2025

Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts

| Content | Chemistry experiments - video | Physics experiments - video | Home Page - Chemistry and Chemists |

|

Chemistry and Chemists № 2 2025 Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts |

Old Acetone Peroxide Disposal Chemist |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

About eight months ago, I synthesized acetone peroxide for a colleague who works with polymer synthesis. This compound, like other organic peroxides, serves as an initiator of radical polymerization. The experiment was successful, the work is complete, and the article is currently under review.

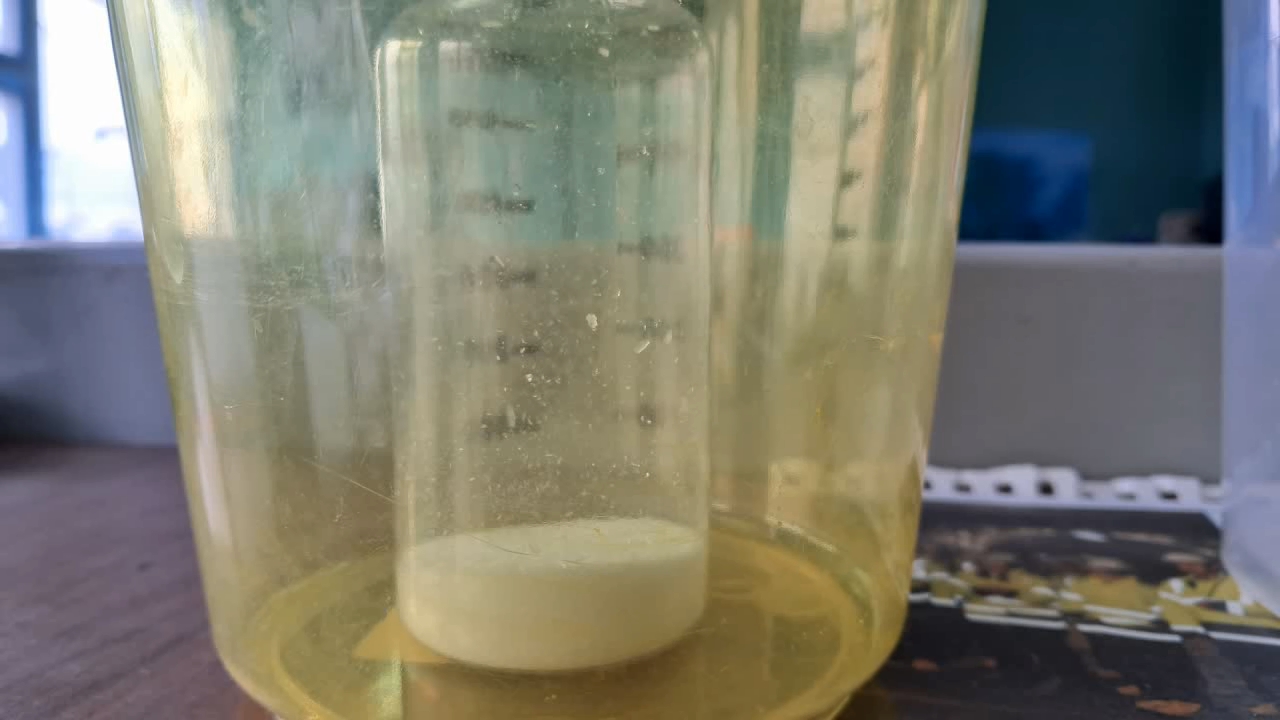

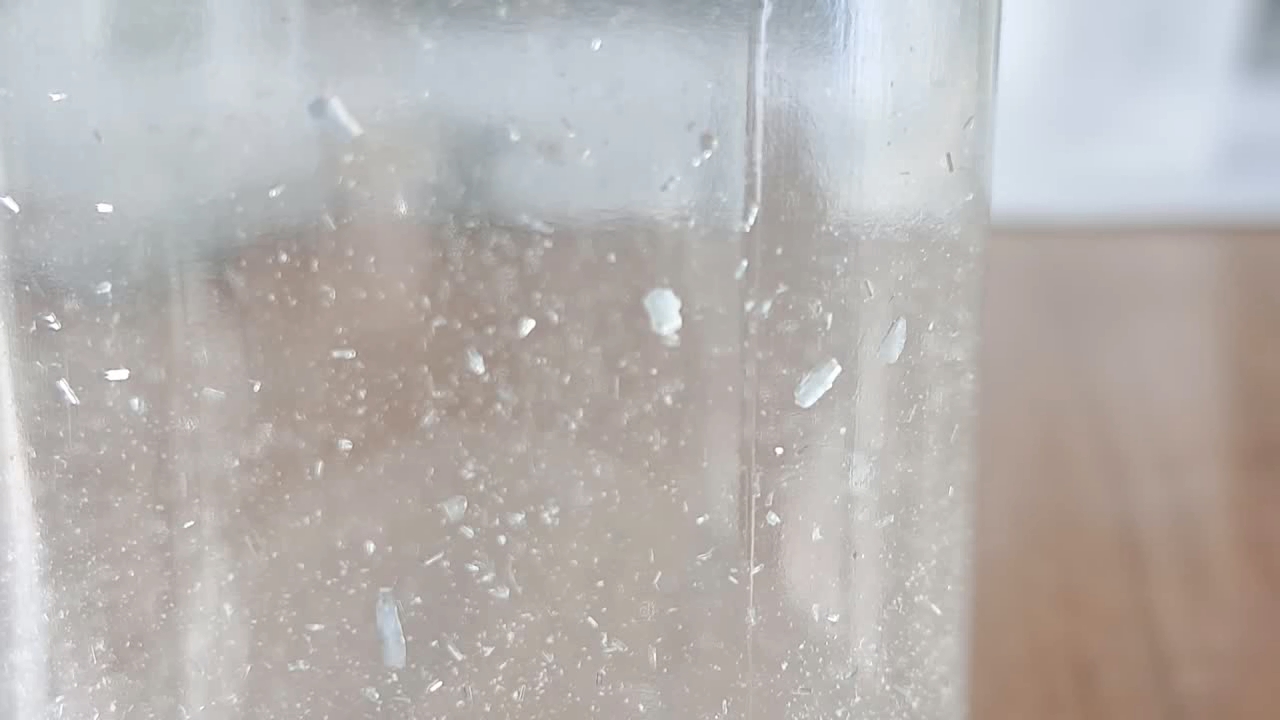

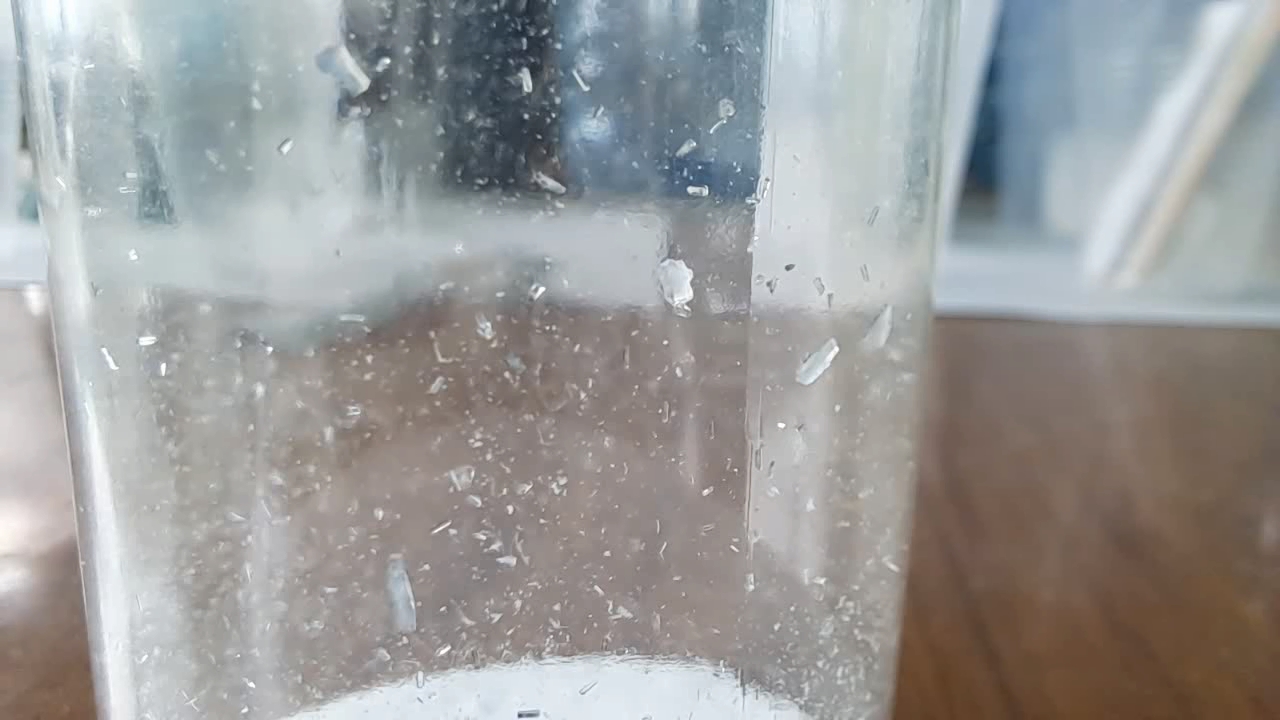

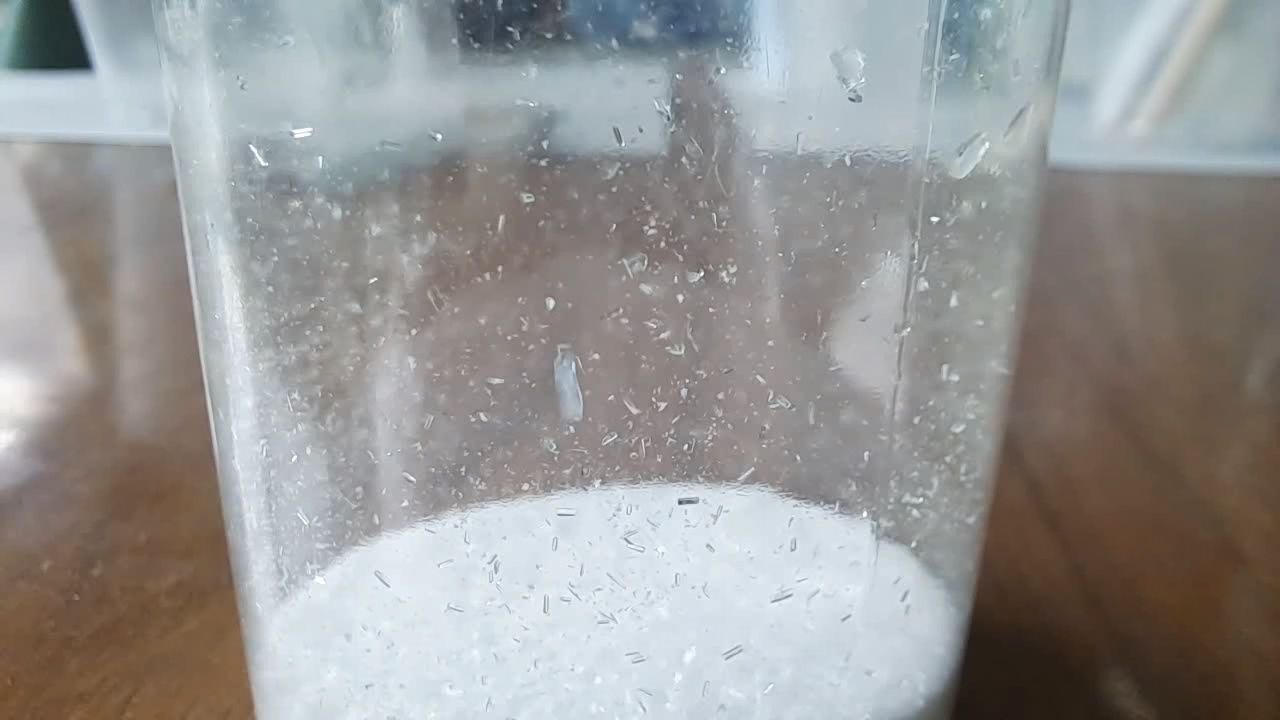

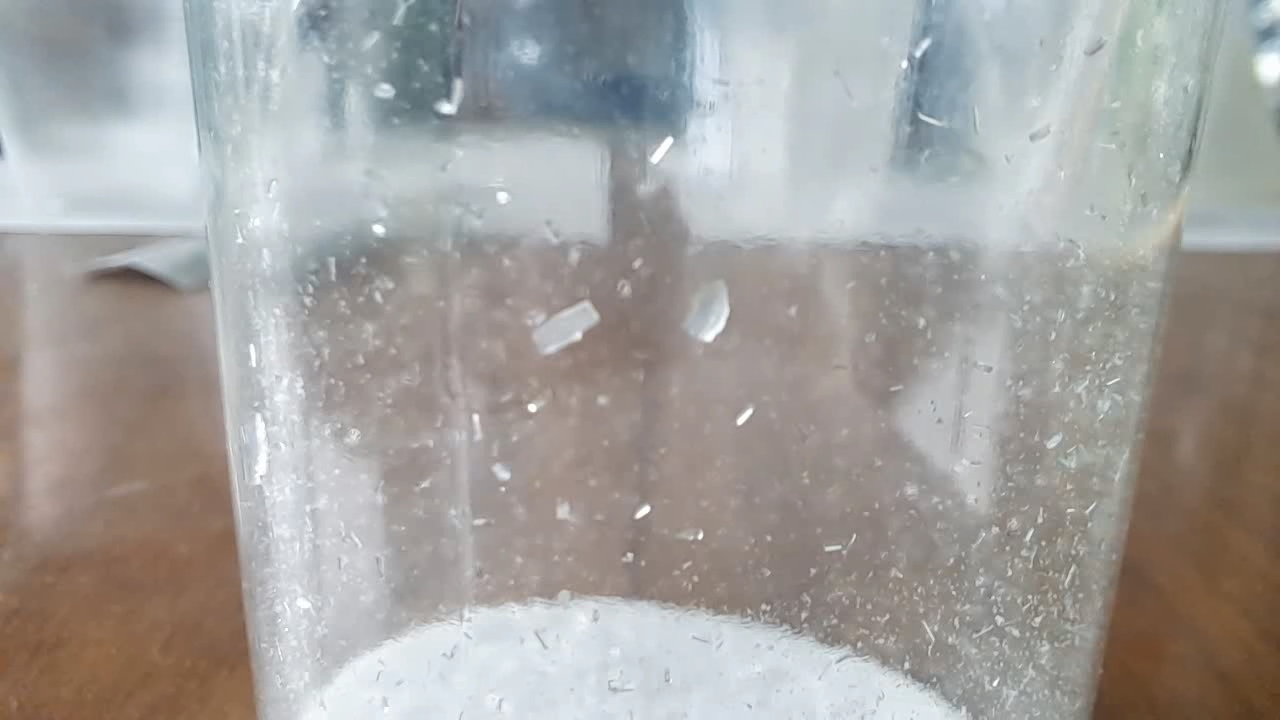

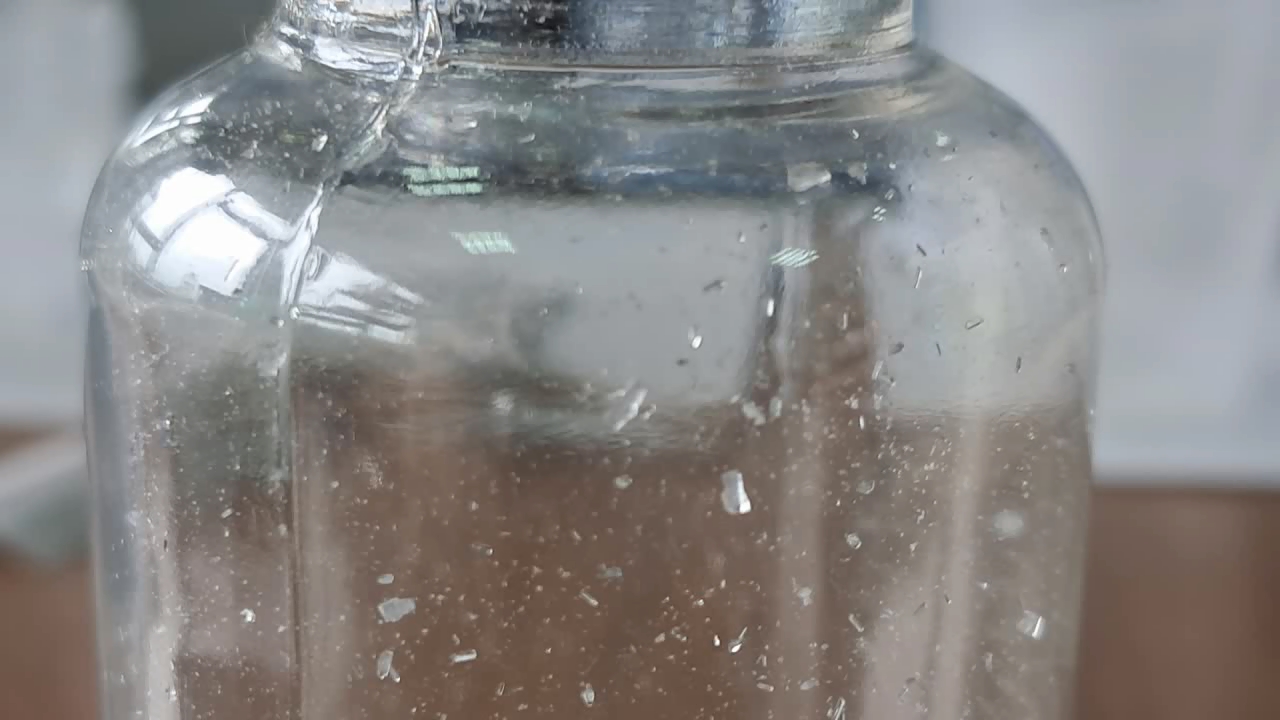

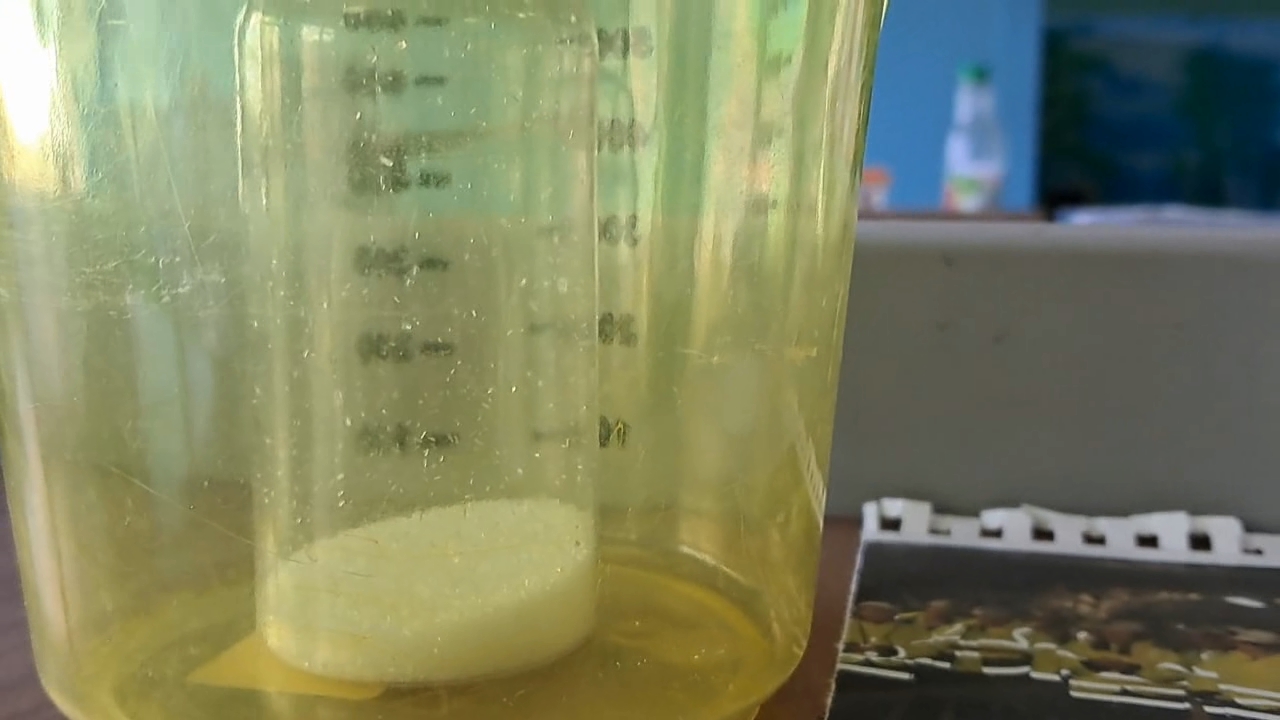

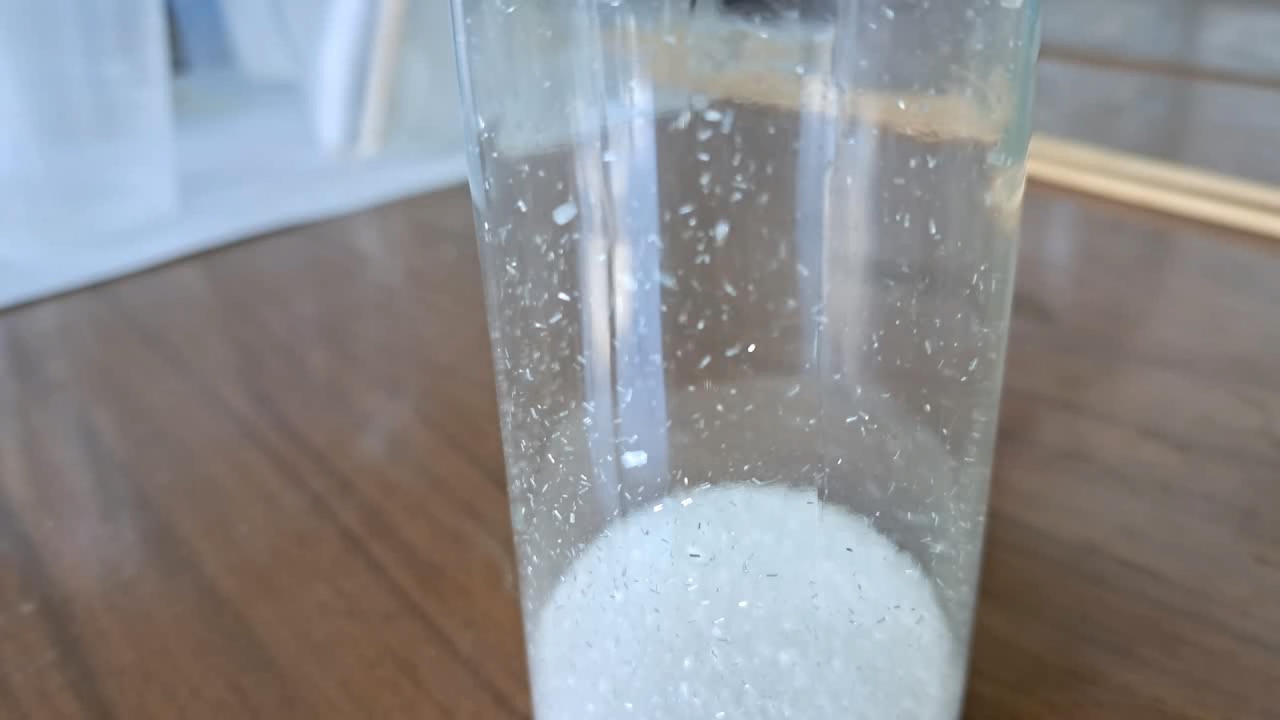

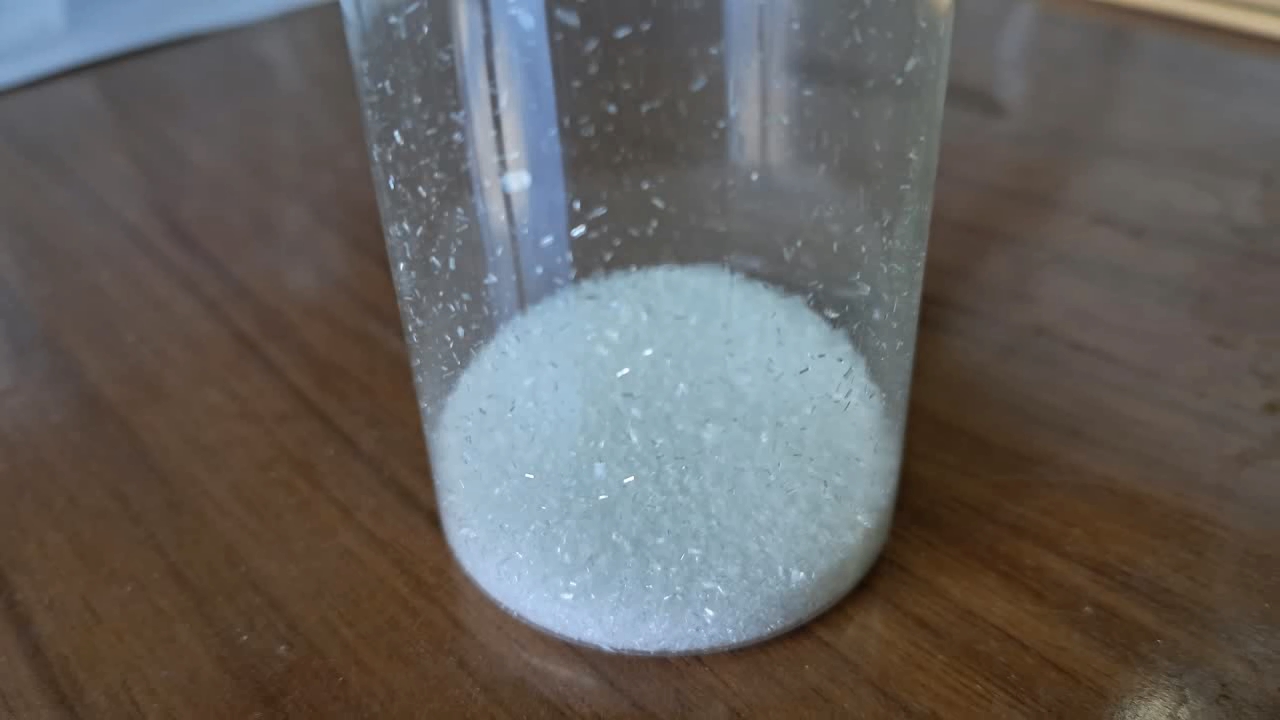

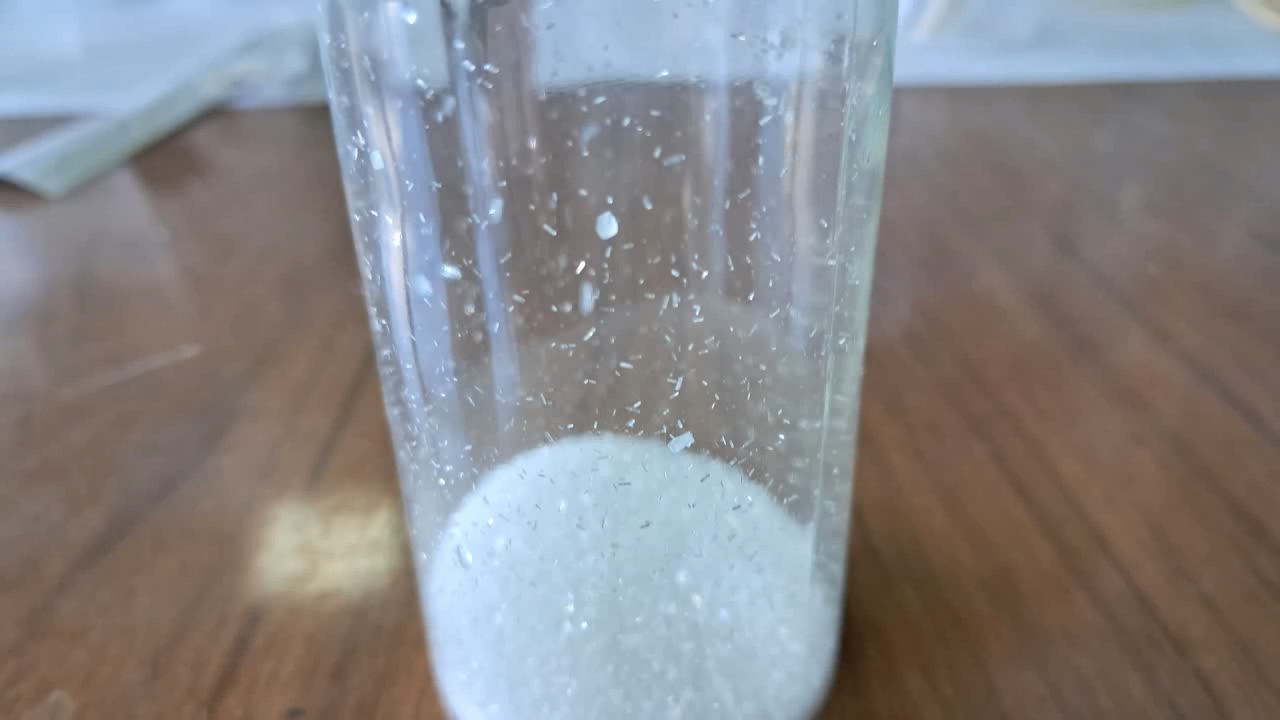

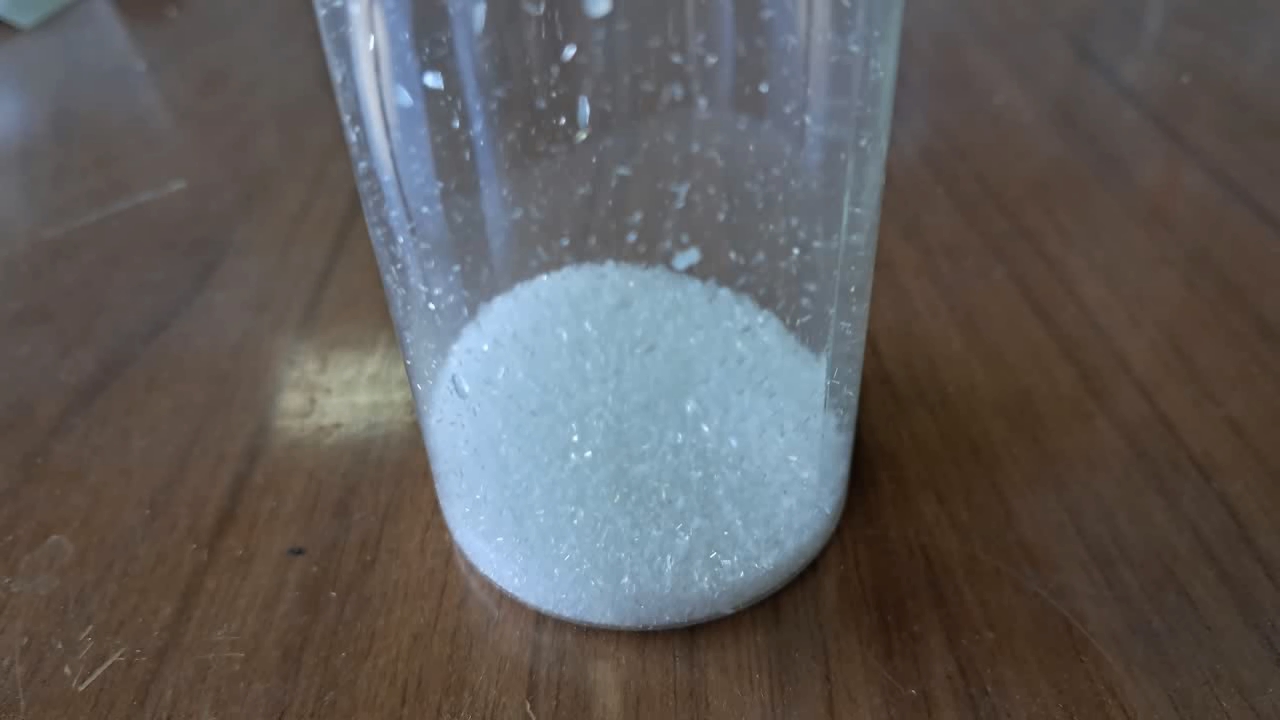

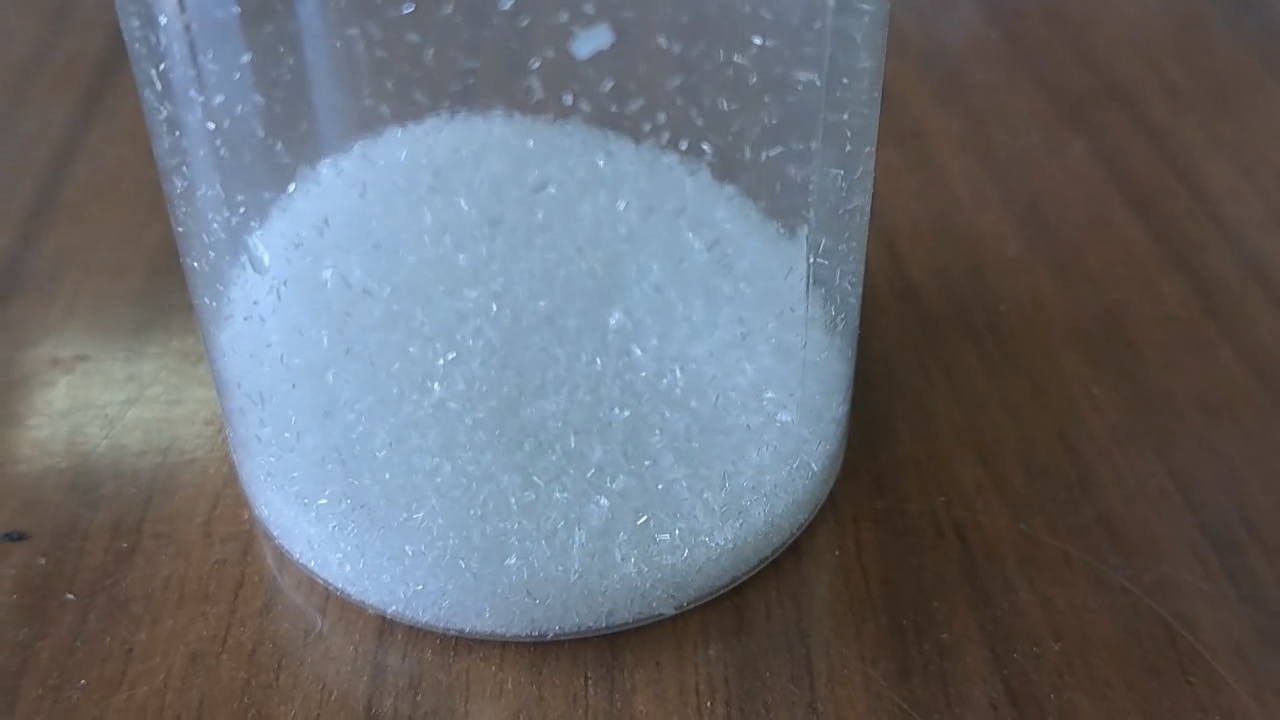

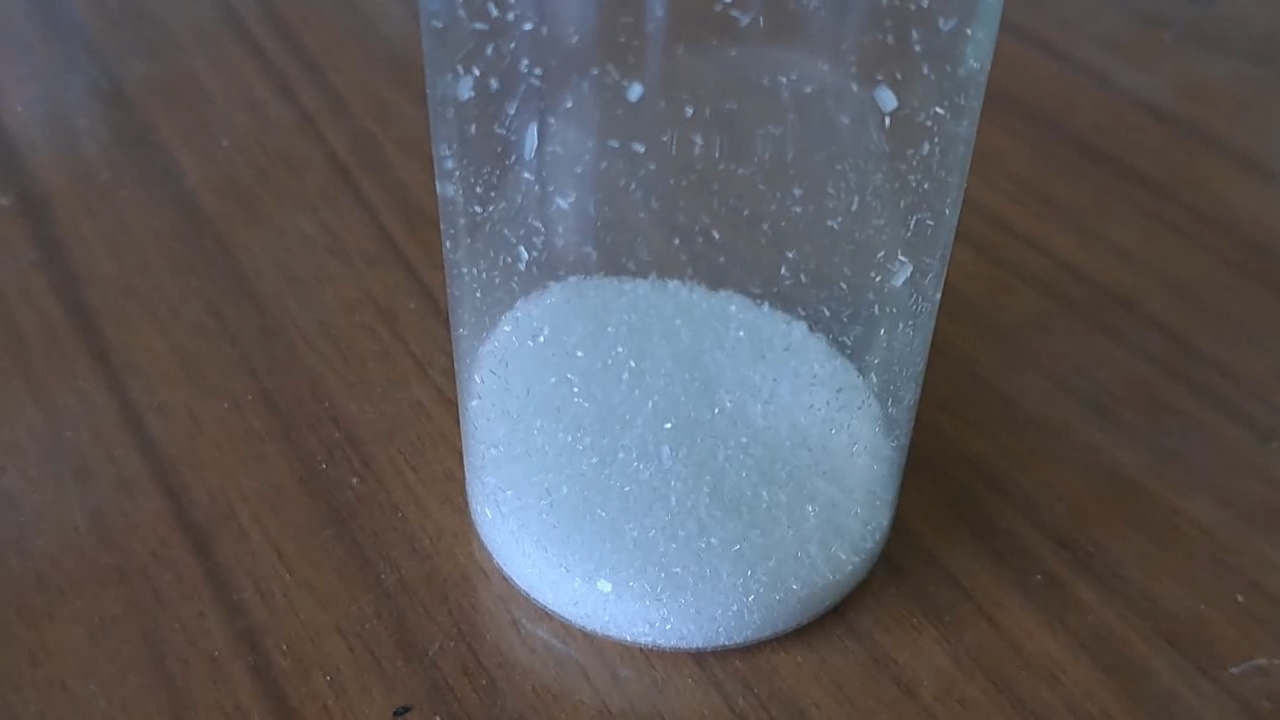

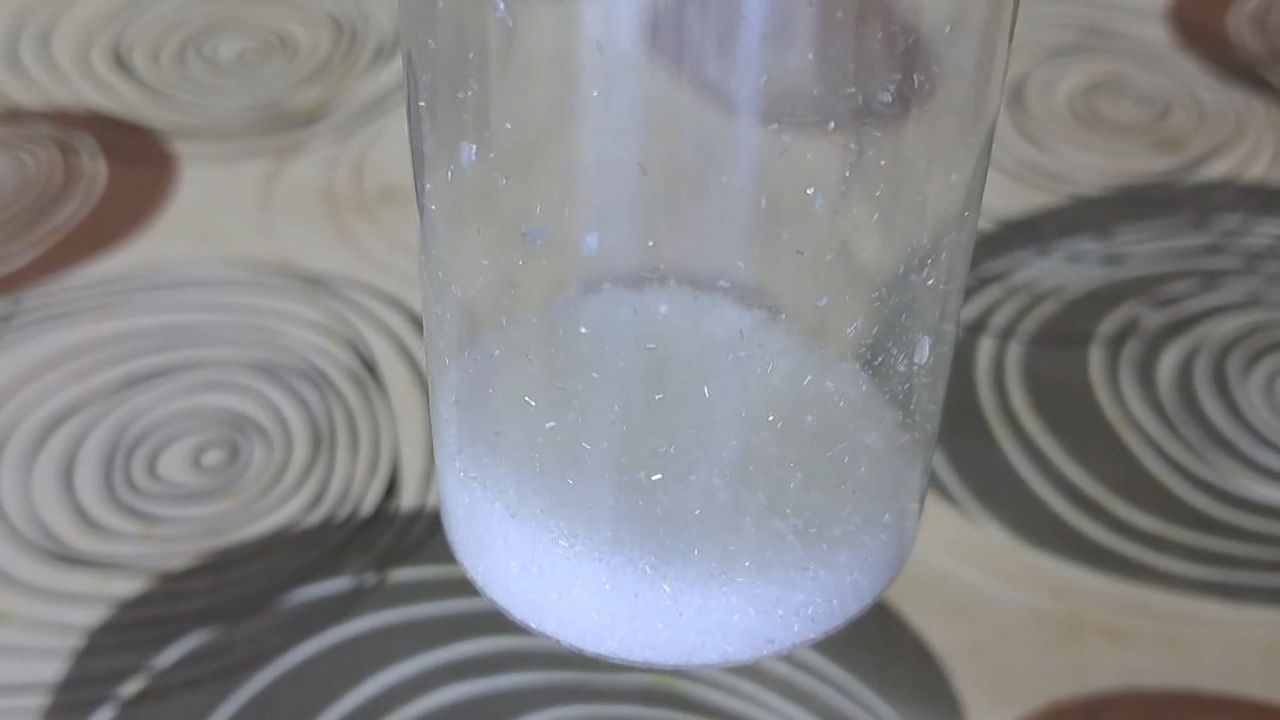

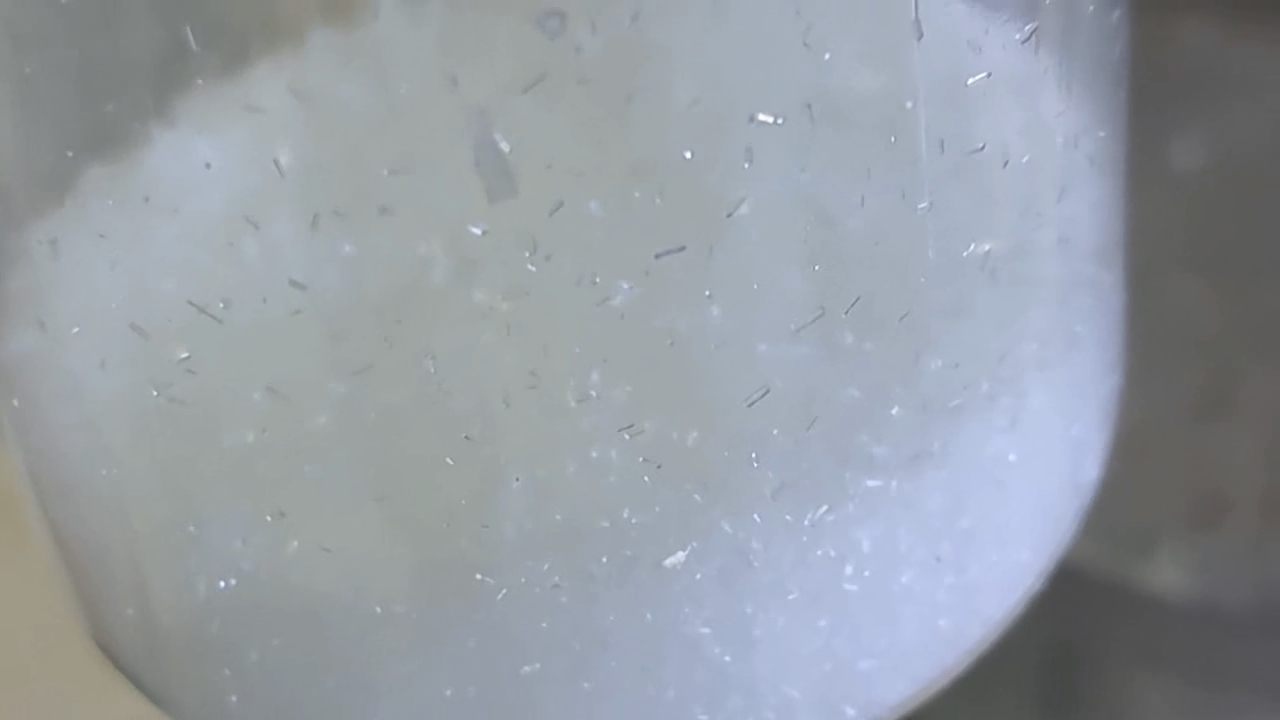

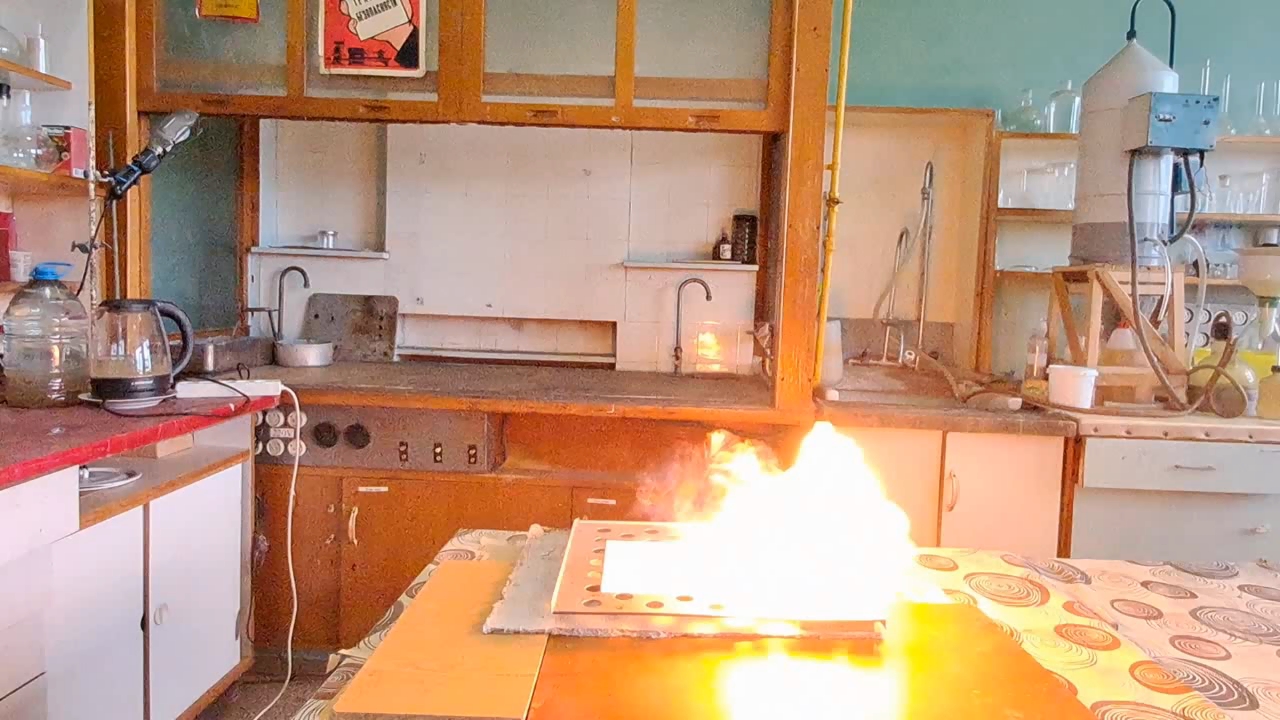

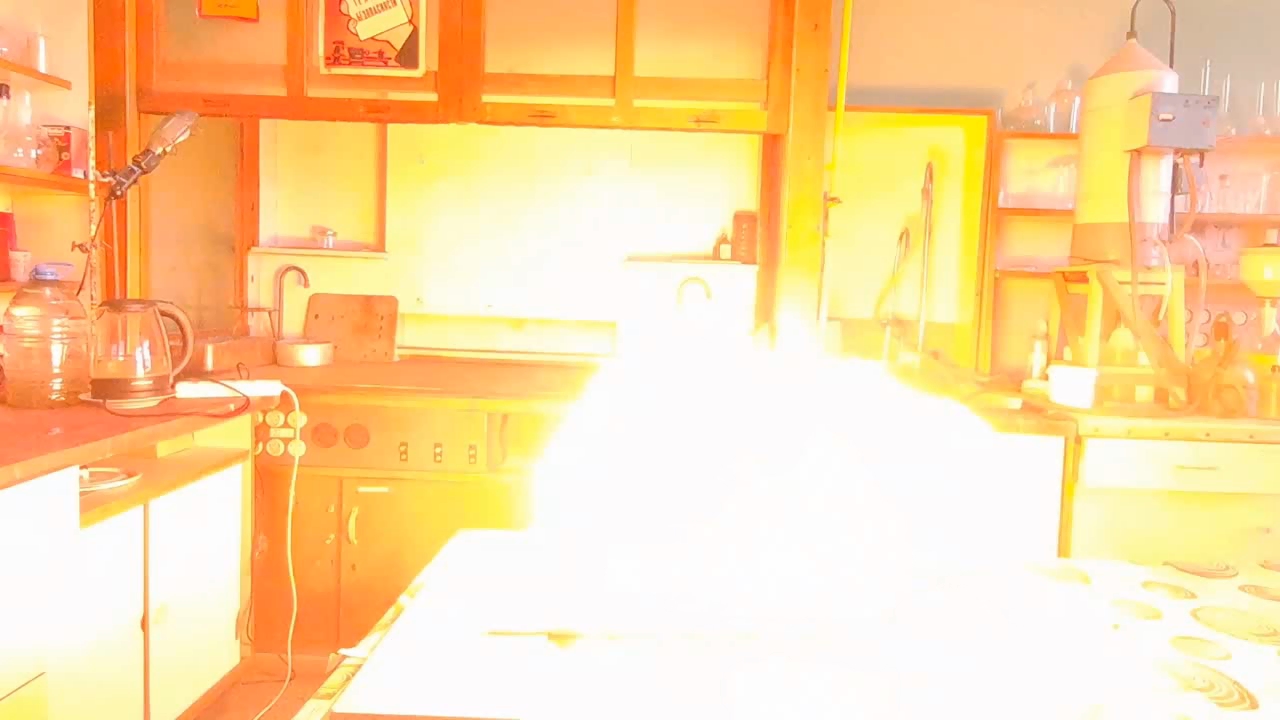

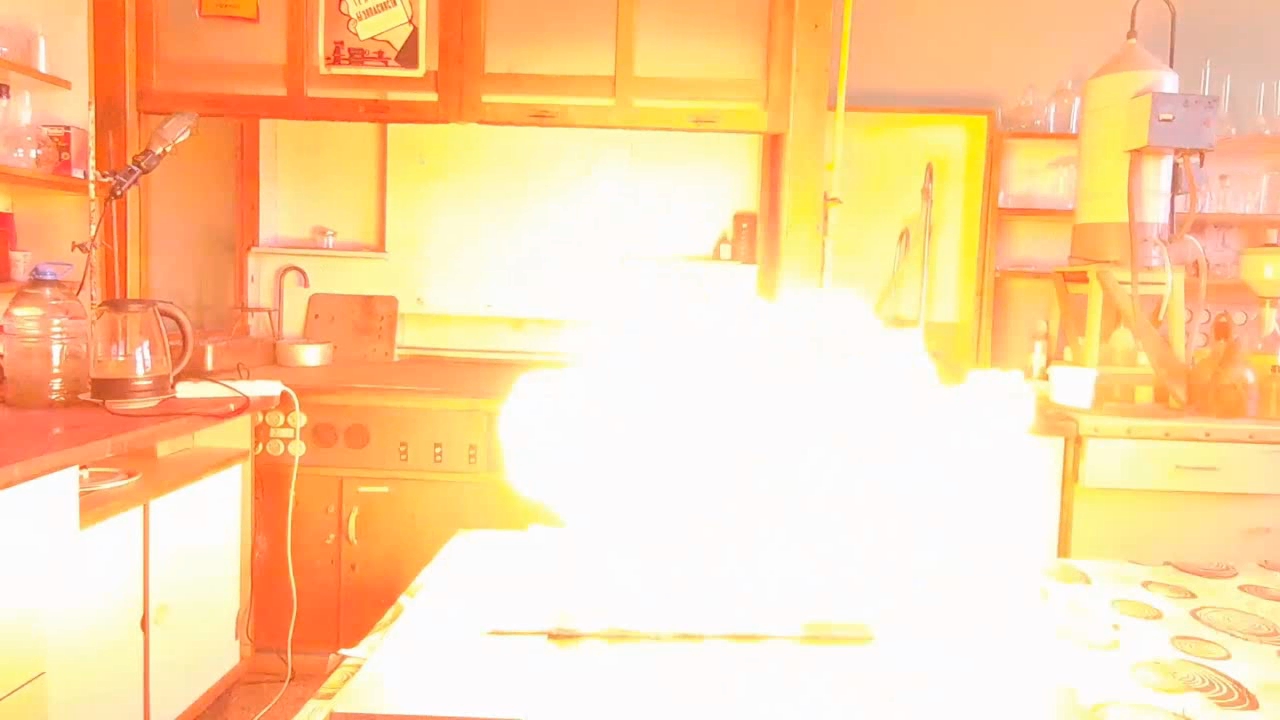

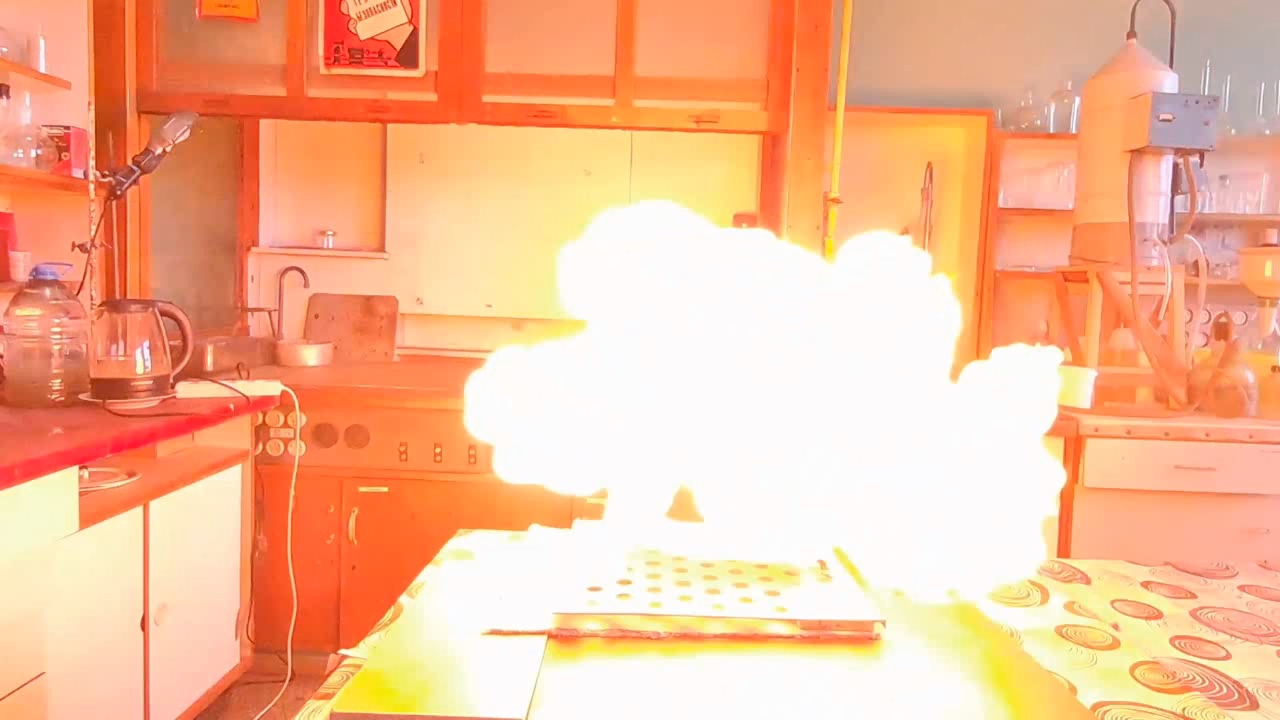

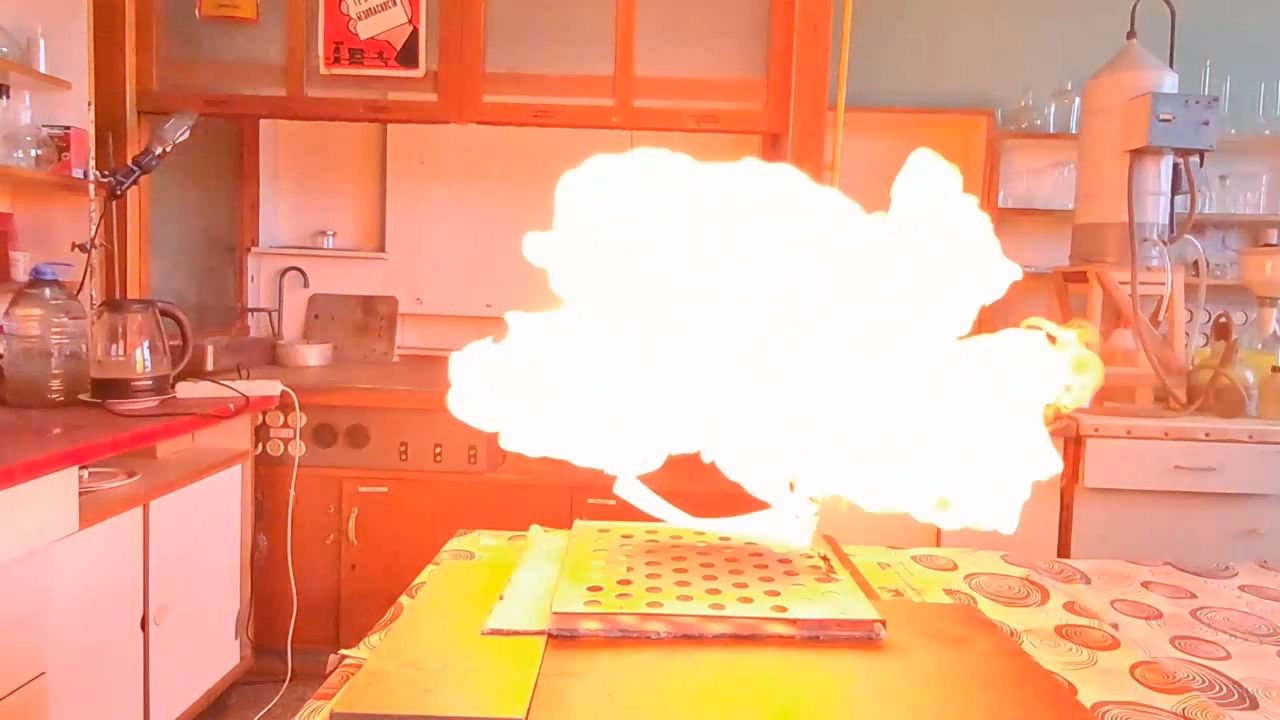

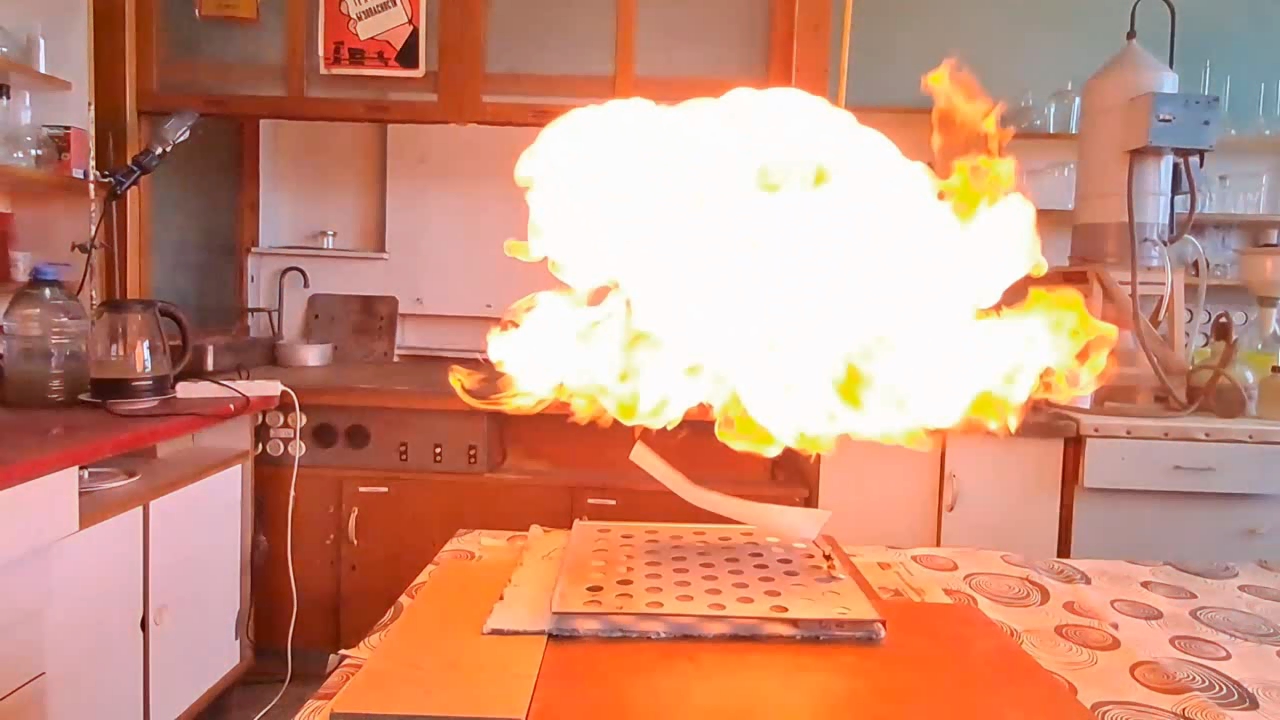

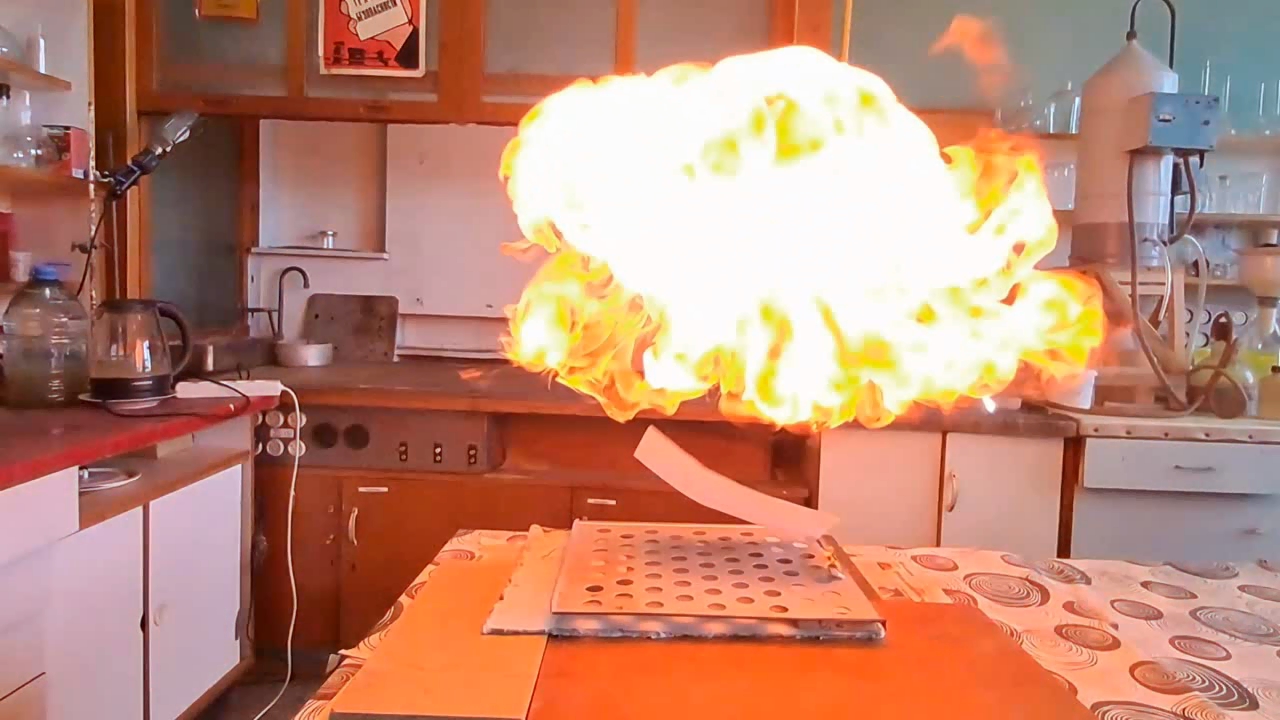

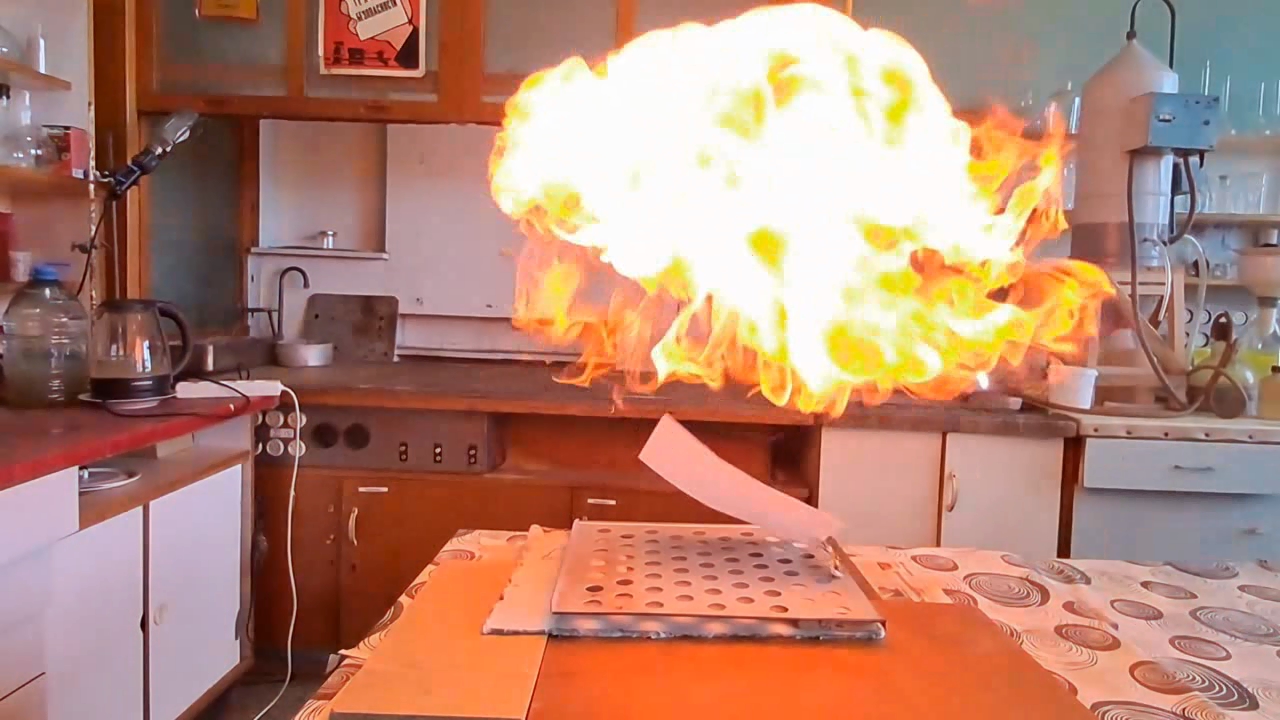

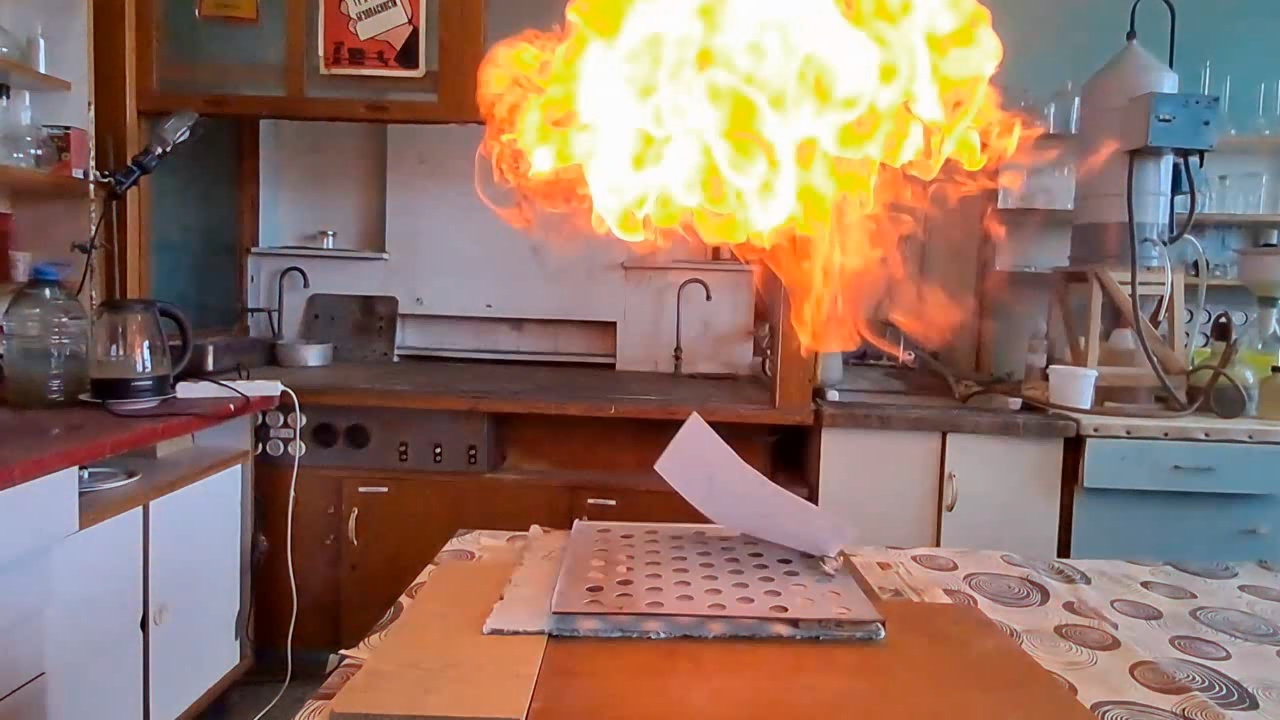

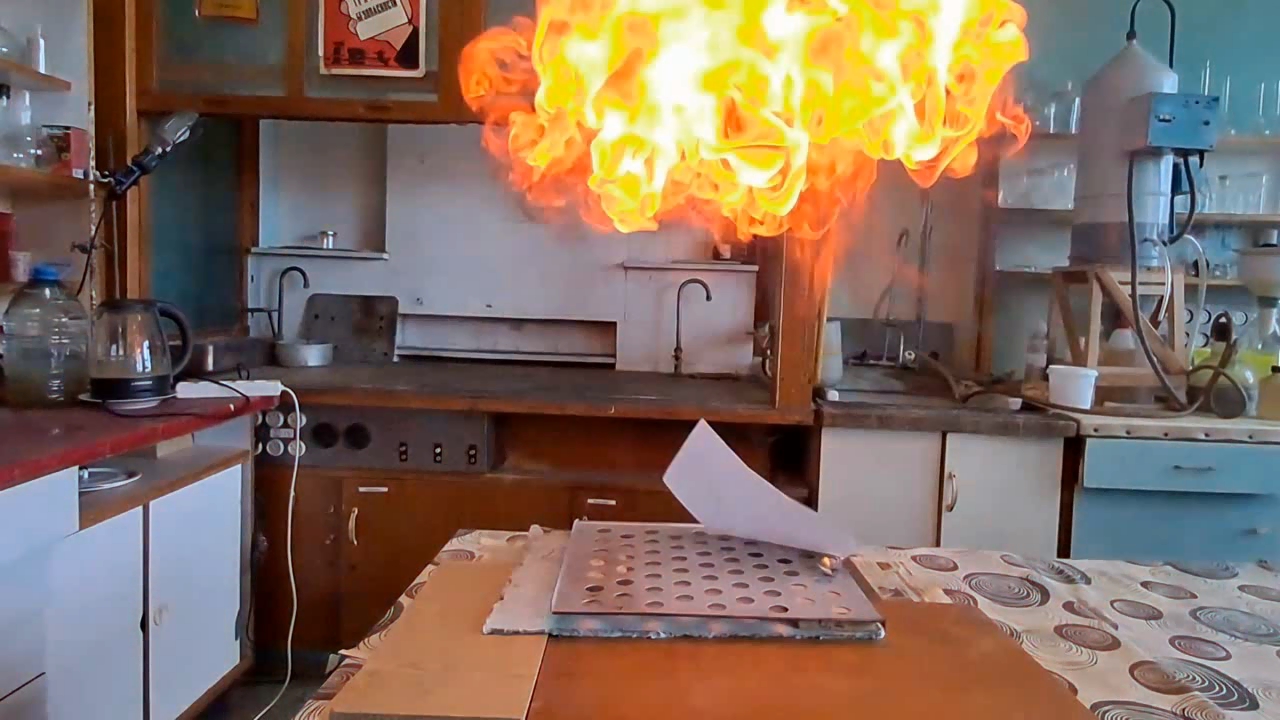

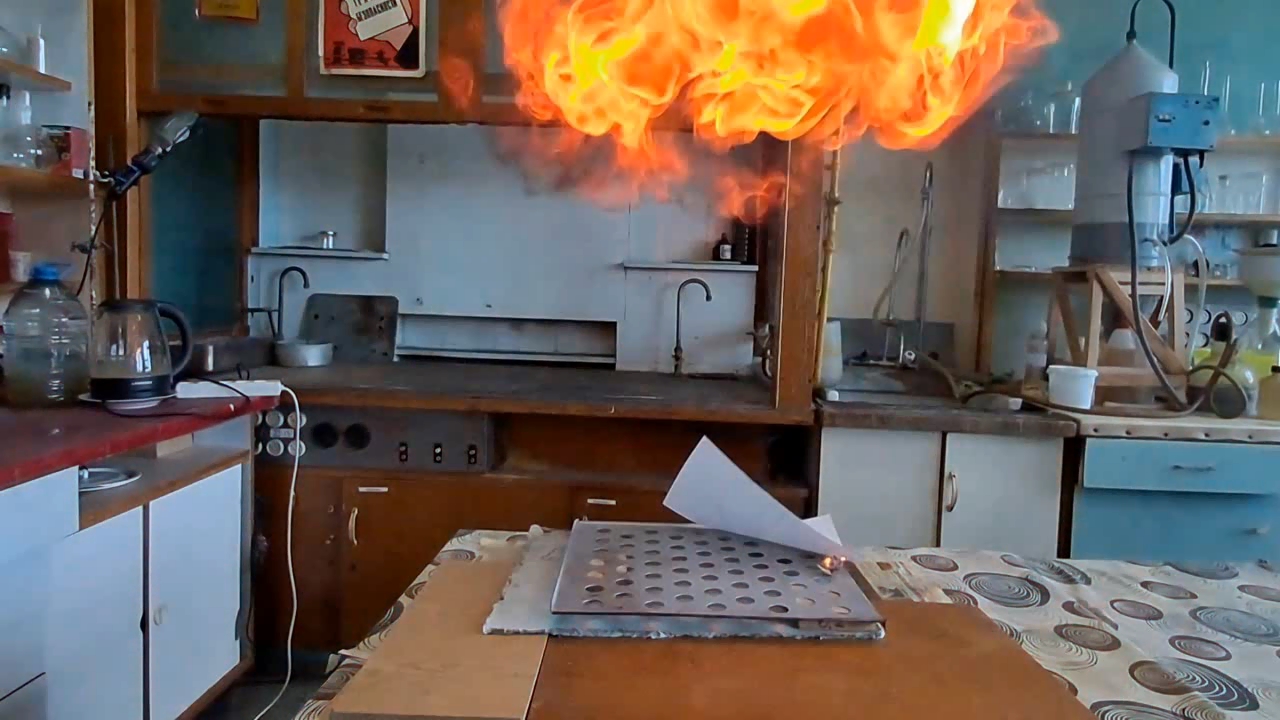

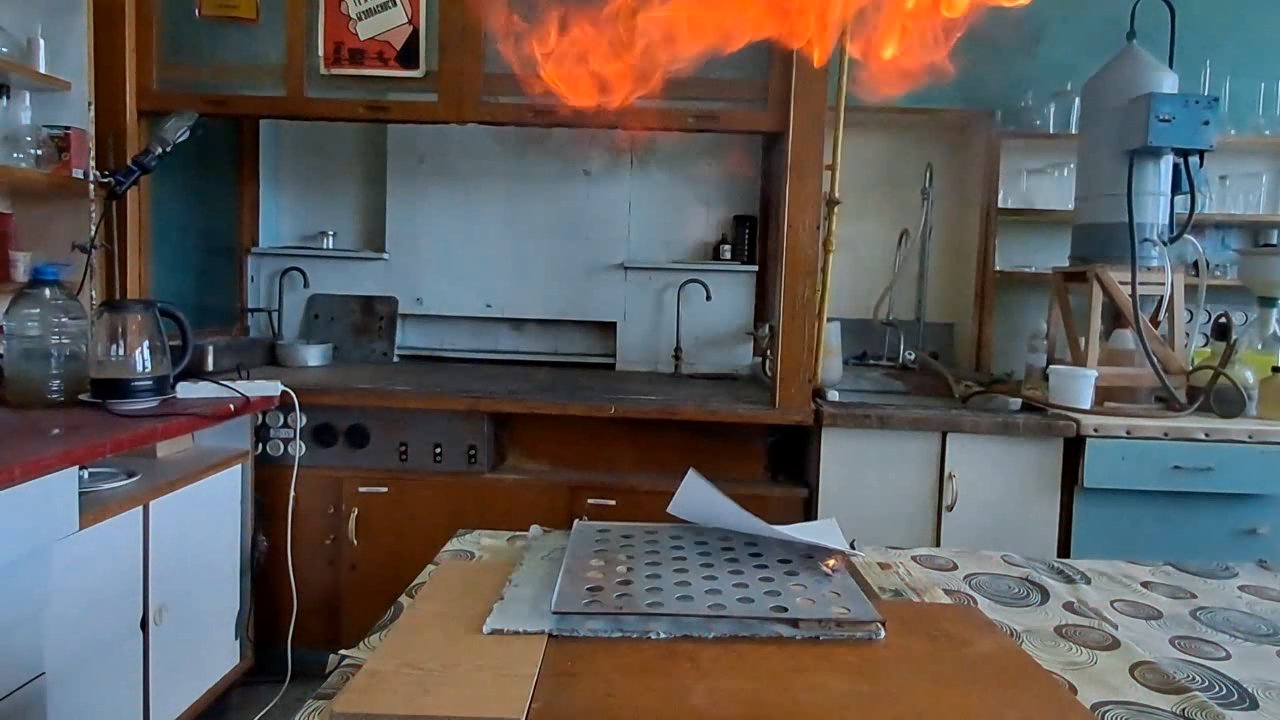

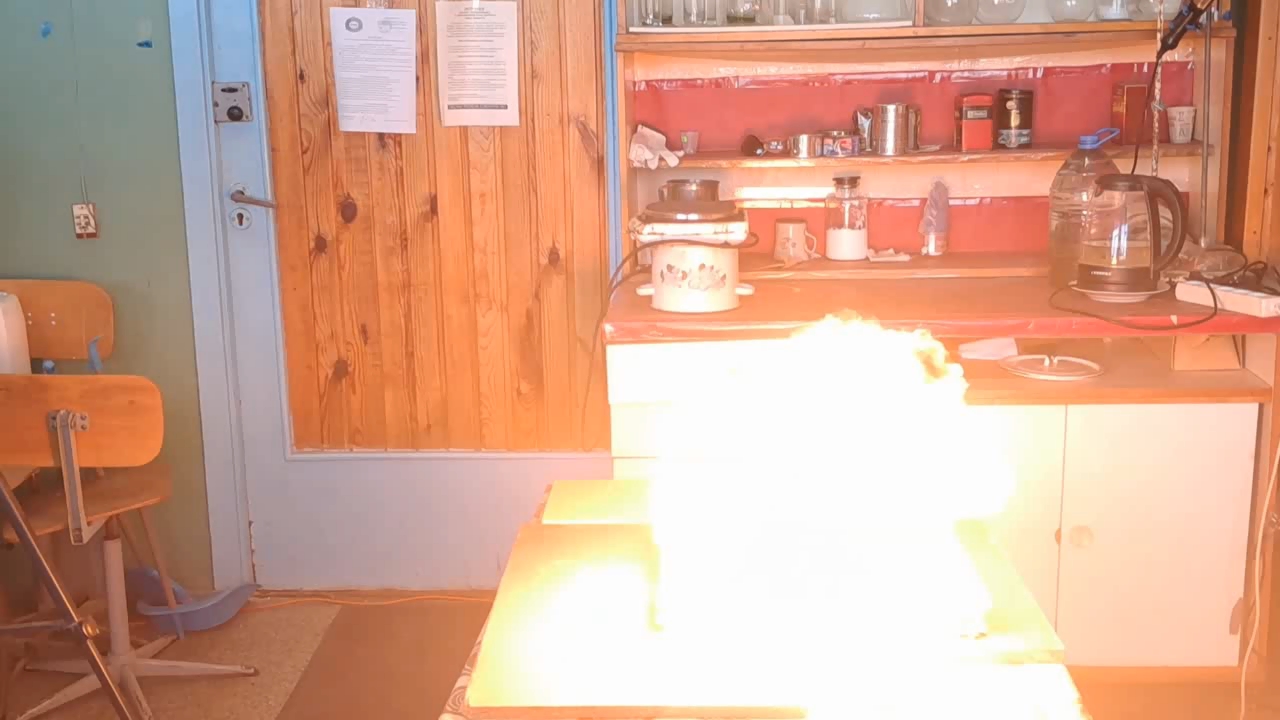

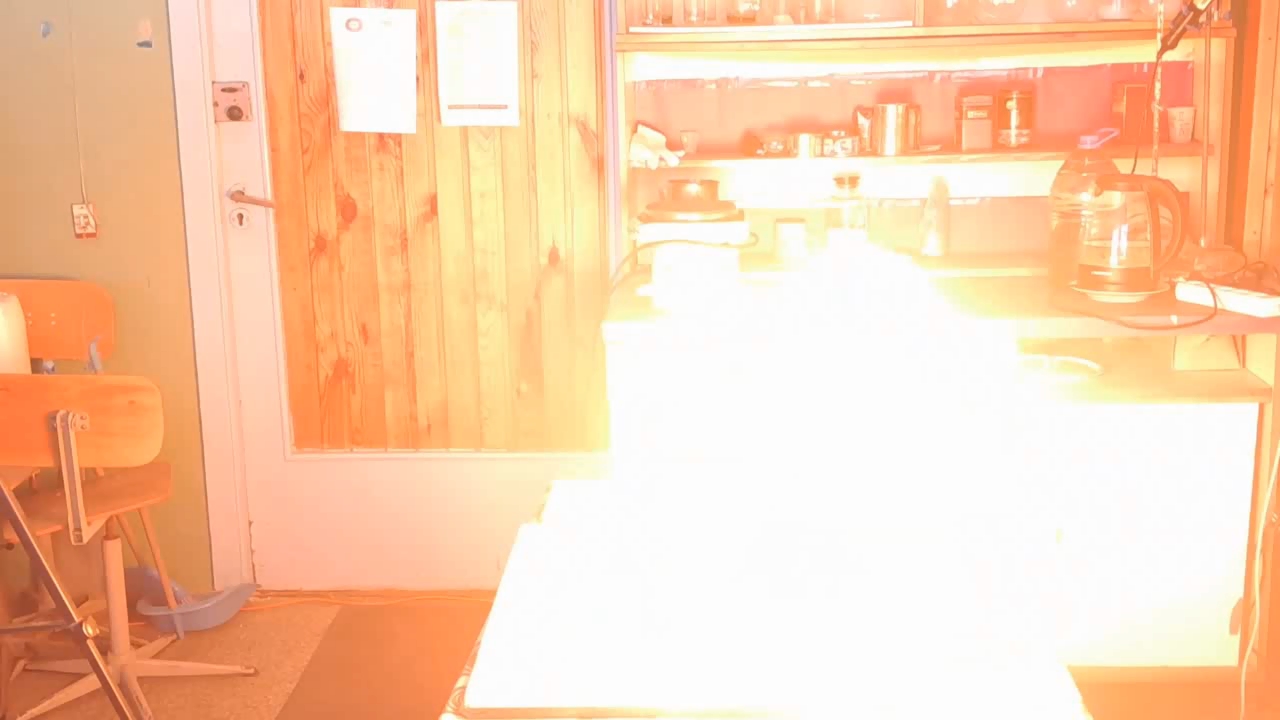

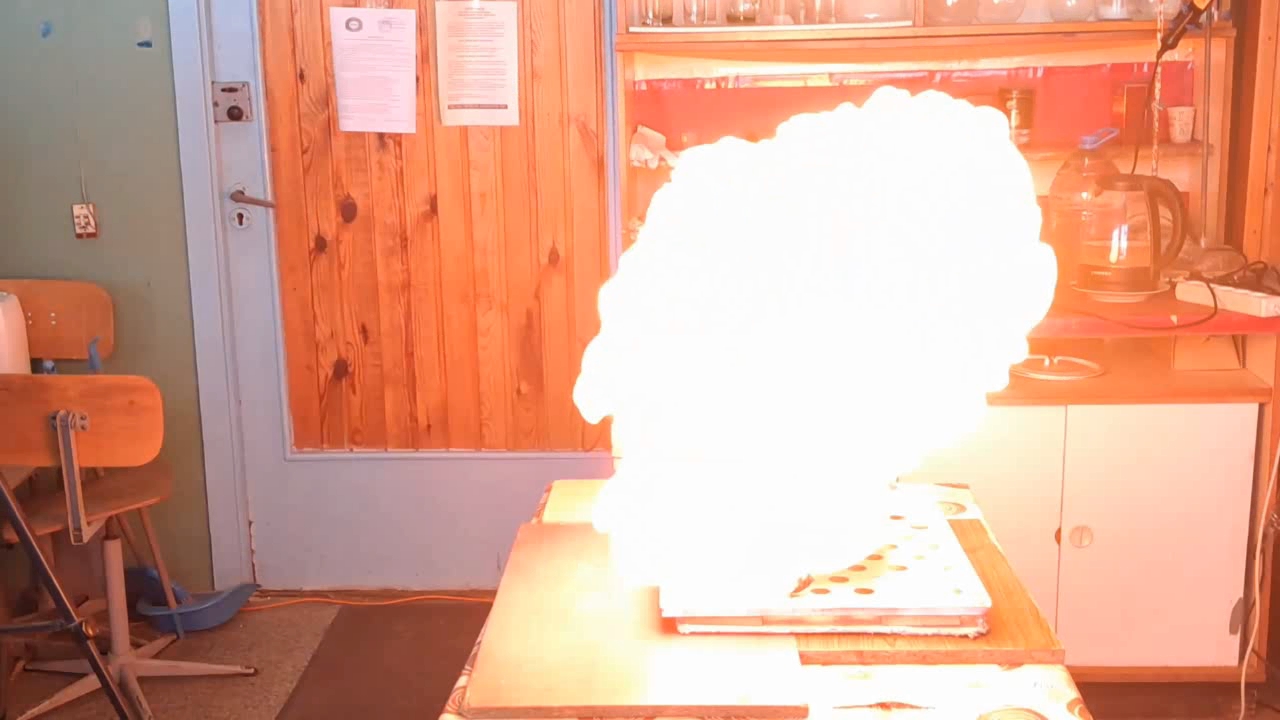

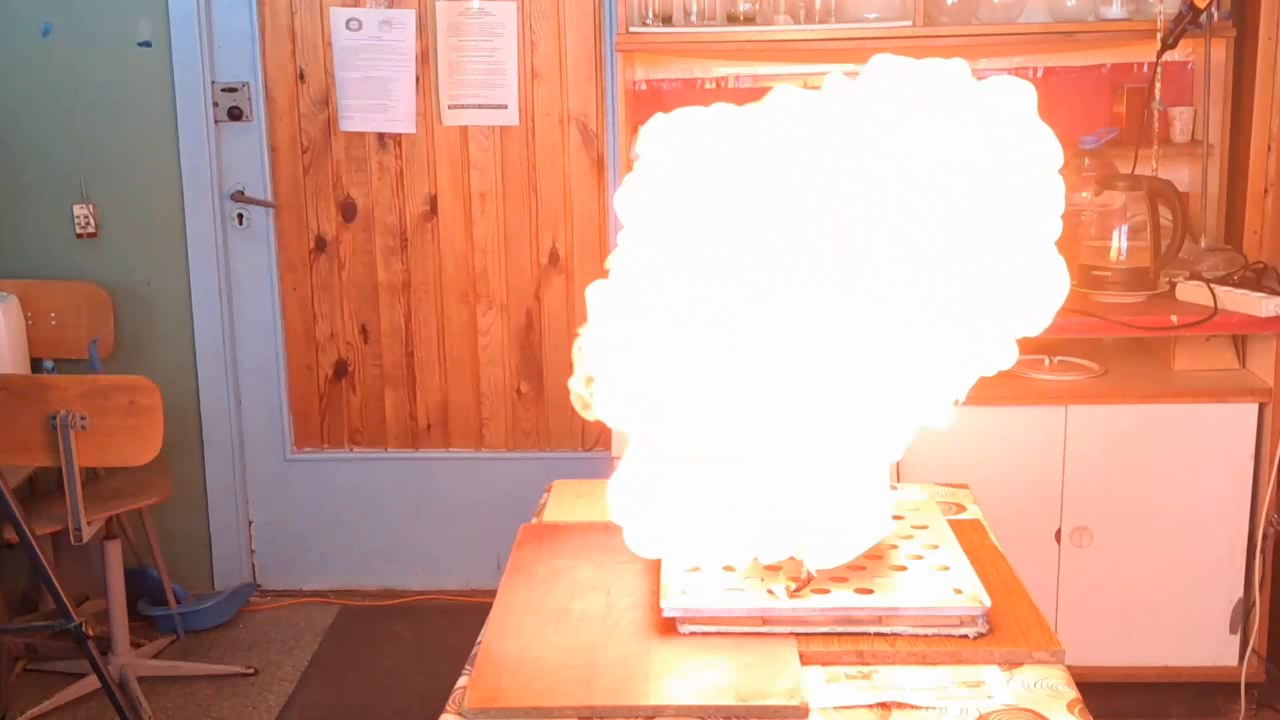

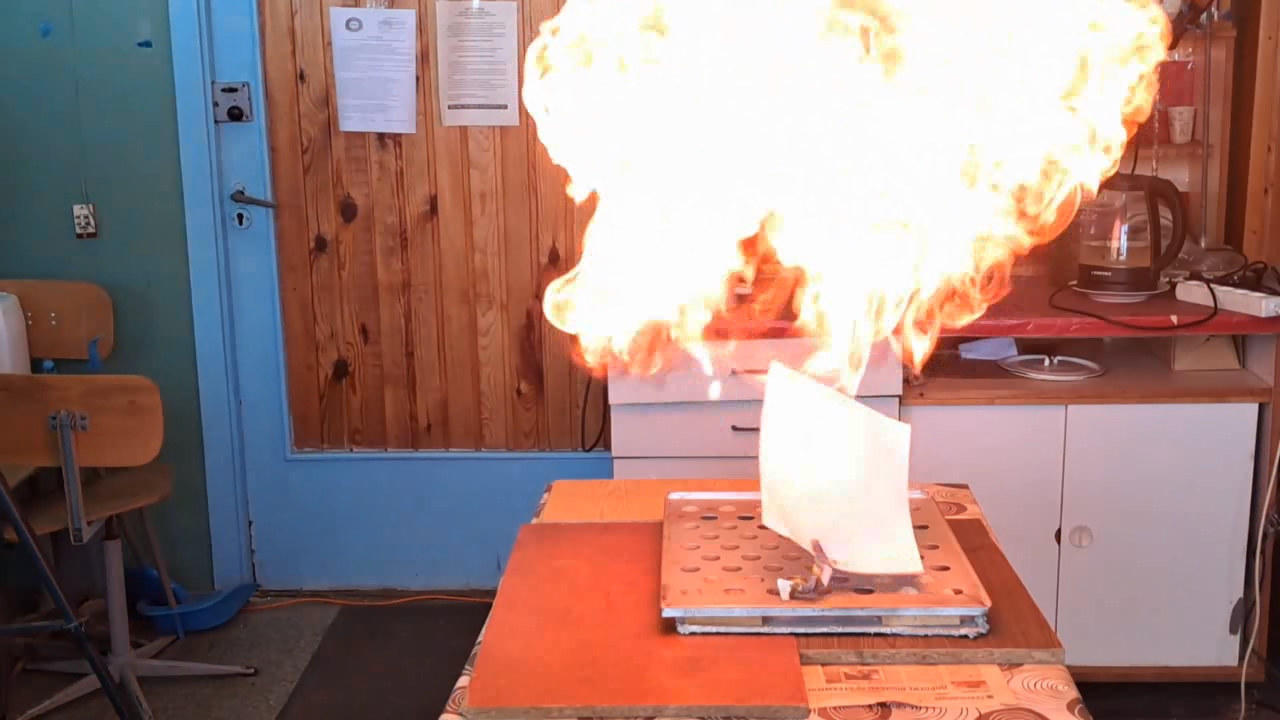

Most of the substance remained unused, so my colleague simply left it on a shelf in a transparent plastic bottle. However, acetone peroxide is not only an initiator of polymerization, but also a sensitive explosive that can easily detonate from friction or impact and is extremely sensitive to heat. Moreover, acetone peroxide crystals sublimate even at room temperature and then condense on the walls of the bottle and the threads of the cap. Attempting to unscrew the cap could result in the detonation of the entire contents. When I visited my colleague, I found that crystals of acetone peroxide had formed on the inner walls of the bottle. Similar crystals could have grown between the cork and the neck of the bottle. Large crystals of acetone peroxide are particularly dangerous. The compound needed to be disposed of immediately. The safest method would have been to carry out the disposal outdoors. However, less than a month had passed since I had accidentally started a fire in the laboratory courtyard. It was unlikely that the staff had forgotten this incident. In order not to alarm anyone, I decided to dispose of the compound indoors. The first task was to safely open the cork. It was made of cotton wool and gauze, wrapped in polyethylene. The risk of an explosion from opening a soft cork was minimal, but it still existed. I put on a protective plexiglass face shield and headphones. I secured the neck of the bottle with a utility clamp (from a retort stand). Using long-handled crucible tongs, I removed the cork - there was no explosion. Next, I placed a sheet of asbestos on the table, then a perforated metal sheet on top, and finally a sheet of paper on top of that. I began to carefully pour the acetone peroxide onto the paper, trying to spread it out in a thin, even layer. I did not hold the bottle in my hand, but kept it fixed in the utility clamp. These precautions were absolutely necessary in case of an unexpected detonation. I was only able to pour out part of the material. It turned out that the crystals had caked together - or rather, had fused during storage. Recrystallization caused by sublimation and subsequent condensation had occurred not only on the bottle walls, but also within the bulk of the acetone peroxide. As a result, the crystals had grown in size and partially fused together. I managed to extract most of the substance by carefully tapping the bottom of the bottle with pliers. Despite considerable effort, the acetone peroxide was reluctant to come out. I stepped away from the sheet containing the material and began tapping the bottom more forcefully. In this way, I was able to extract most of the remaining peroxide. A small amount of acetone peroxide remained tightly stuck to the bottom and walls of the bottle. I didn't attempt to scrape off these crystals; instead, I simply poured water into the bottle, hoping they would decompose over time. However, two weeks passed, and the crystals remained unchanged [UPD]. The bulk of the substance had already been poured onto a sheet of paper. Now it was time to ignite the acetone peroxide. A notable characteristic of this compound is that when subjected to impact, friction, or burning in a confined space, it detonates. However, when spread out in a thin layer in an open area, it ignites when exposed to flame and burns without exploding. That said, if a large amount burns, even in open air, the combustion can escalate into an explosion. In this case, there were about 10 grams of the substance, so I couldn't predict exactly how it would behave. I was well aware that even a much smaller amount of acetone peroxide can cause serious damage. To reduce the risk of explosion, I spread the crystals as thinly as possible across the paper. How can one safely ignite a substance that may explode? A fuse is essential. I initially planned to use a strip of paper, but it burned unevenly and kept going out. A colleague suggested using a mixture of potassium nitrate and sugar. I wasn't keen on looking for potassium nitrate and sugar and then preparing the mixture, so I looked for alternatives. Eventually, I found smokeless powder (nitrocellulose). I laid out a narrow trail of smokeless powder on a strip of paper. Then I took a torch and tried to ignite the paper - but the gas in the canister had run out. I replaced the canister and discovered that the torch had lost its seal: aerosolized butane sprayed in all directions. That explained why the previous canister had emptied so quickly. I quickly detached the canister to avoid further danger. In the end, I had to light the paper with a regular lighter - and succeeded on the second attempt. When the flame reached the acetone peroxide, it produced a bright yellow flash accompanied by a characteristic popping sound. A fireball shot upward, producing black soot. Despite the significant number of oxygen atoms in the acetone peroxide molecule, its overall oxygen balance is negative. The flame was intense; however, the paper beneath didn't ignite or even char after the flash. The sheet only began to burn a few seconds later, accidentally ignited by the strip of paper used as a fuse. ____________________________ UPD. I poured water from the bottle. The acetone peroxide crystals completely evaporated in two days. |

|

Утилизация старой перекиси ацетона

Примерно восемь месяцев назад я синтезировал пероксид ацетона для коллеги, который занимается синтезом полимеров. Данное вещество, подобно другим органическим перекисям, является инициатором радикальной полимеризации. Эксперимент завершился успешно, работа окончена, статья проходит рецензирование.

Большая часть вещества осталась неиспользованной, поэтому коллега просто оставил его на полке в прозрачной пластиковой бутылке. С другой стороны, перекись ацетона является не только инициатором полимеризации, но и чувствительным взрывчатым веществом, которое легко детонирует от трения или удара, весьма чувствительно к огню. Более того, кристаллы перекиси ацетона сублимируются даже при комнатной температуре, а затем конденсируются на стенках бутылки и резьбе крышки. Попытка открутить крышку может привести к взрыву всего количества вещества. Придя в гости к коллеге, я обнаружил, что кристаллы перекиси ацетона выросли на стенках бутылки. Такие же кристаллы могли вырасти между пробкой и горлом бутылки. Крупные кристаллы перекиси ацетона особенно опасны. Вещество было необходимо срочно утилизировать. Безопаснее всего было провести этот процесс за пределами помещения, однако, не прошло и месяца с тех пор, как я случайно устроил пожар во дворе лаборатории. Вряд ли сотрудники успели забыть это событие. Чтобы не пугать людей, решил провести утилизацию вещества в помещении. Первая задача - безопасно открыть пробку. Пробка была из ваты и марли, обернутая полиэтиленом. Вероятность взрыва при открытии мягкой пробки была минимальна, но риск оставался. Надел защитную маску из оргстекла и наушники. Зажал горлышко бутылки в лапке лабораторного штатива. С помощью тигельных щипцов с длинной ручкой открыл пробку - обошлось без взрыва. Далее поместил на стол лист асбеста, на него - перфорированный металлический лист. Сверху постелил лист бумаги. Начал осторожно высыпать перекись ацетона из бутылки на бумагу, стараясь распределить ее тонким равномерным слоем. При этом я не держал бутылку в руке - она была зажата в лапке штатива. Такая предосторожность абсолютно необходима на случай неожиданного взрыва. Высыпать удалось лишь часть вещества. Оказалось, что кристаллы слежались, точнее - срослись во время хранения. Перекристаллизация за счет сублимации с последующей конденсацией происходила не только на стенках бутылки, но и внутри слоя перекиси ацетона. В результате размер кристаллов увеличивался, а сами кристаллы частично срослись между собой. Осторожно постукивая по дну бутылки плоскогубцами, мне удалось высыпать большую часть вещества. Несмотря на значительные усилия, перекись ацетона высыпалась неохотно. Отошел подальше от листа с веществом и стал стучать по дну сильнее. Таким способом удалось извлечь большую часть перекиси ацетона. Небольшое количество перекиси ацетона намертво пристало к дну и стенкам бутылки. Не стал отскребать эти кристаллы, просто залил бутылку водой. Надеялся, что они разложатся со временем. Однако, прошло уже две недели, а кристаллы по-прежнему не изменились [UPD]. Итак, основную массу вещества удалось высыпать на лист бумаги. Теперь предстояло поджечь перекись ацетона. Особенность данного вещества в том, что при ударе, трении или сгорании в закрытом объеме перекись ацетона взрывается. Однако, при действии огня на перекись ацетона, рассыпанную тонким слоем на открытом пространстве, вещество вспыхивает и сгорает без взрыва. Разумеется, при сгорании большого количества вещества, горение может перейти во взрыв даже на открытом пространстве. В нашем случае количество вещества было около 10 грамм, как поведет себя перекись ацетона, я не знал. Однако я помнил, что взрыв гораздо меньшего количества перекиси ацетона может причинить большой ущерб. Чтобы избежать взрыва, распределил вещество как можно более тонким слоем по бумаге. Как безопасно поджечь вещество, которое может взорваться? Необходим замедлитель (фитиль). Решил использовать для этой цели полоску бумаги, однако, она горела неравномерно и часто гасла. Коллега предложил приготовить смесь нитрата калия и сахара. У меня не было желания искать нитрат калия и сахар, а потом их смешивать. Зато нашел бездымный порох (нитроцеллюлоза). На полоску бумаги насыпал дорожку из бездымного пороха. Взял горелку, попытался поджечь бумагу - в баллончике закончился газ. Поменял баллончик и обнаружил, что горелка потеряла герметичность: аэрозоль сжиженного бутана полетел во все стороны. Именно поэтому газ в предыдущем баллончике закончился. Срочно отсоединил баллончик от горелки. Пришлось поджечь бумажку обычной зажигалкой - со второго раза это удалось. Когда пламя коснулось перекиси ацетона, произошла сильная желтая вспышка с характерным хлопком. Огненное облако устремилось вверх, образовав черную копоть. Несмотря на значительное количество атомов кислорода в молекуле перекиси ацетона, кислородный баланс данного вещества отрицательный. Пламя было очень сильным, однако, бумага после вспышки перекиси ацетона не загорелась и даже не обуглилась. Горение листа началось на несколько секунд позже, когда его случайно подожгла полоска бумаги, использованная в качестве фитиля. ____________________________ UPD. Вылил воду из бутылки. Кристаллы перекиси ацетона за два дня полностью испарились. |

Old Acetone Peroxide Disposal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|