Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2024

Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts

| Content | Chemistry experiments - video | Physics experiments - video | Home Page - Chemistry and Chemists |

|

Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2024 Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts |

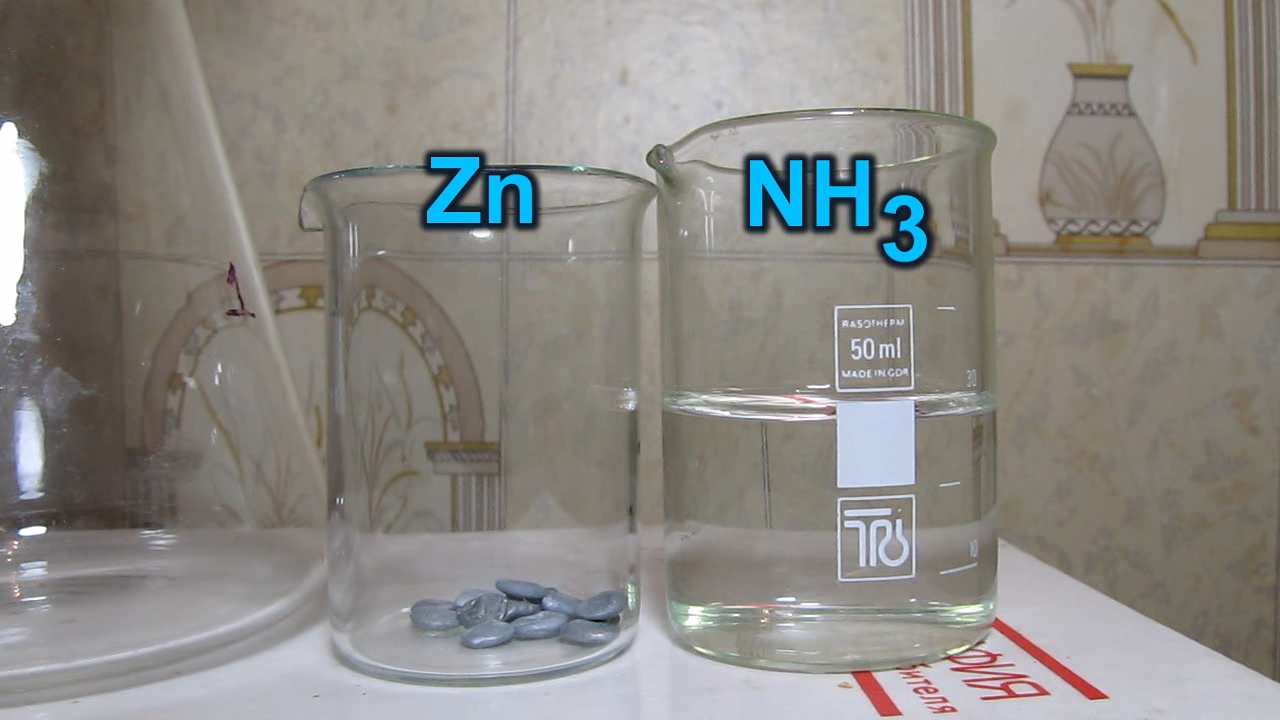

Zinc, ammonia and air (reaction of zinc metal with aqueous ammonia and oxygen) V.M. Viter |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

Zinc, ammonia and air (reaction of zinc metal with aqueous ammonia and oxygen)

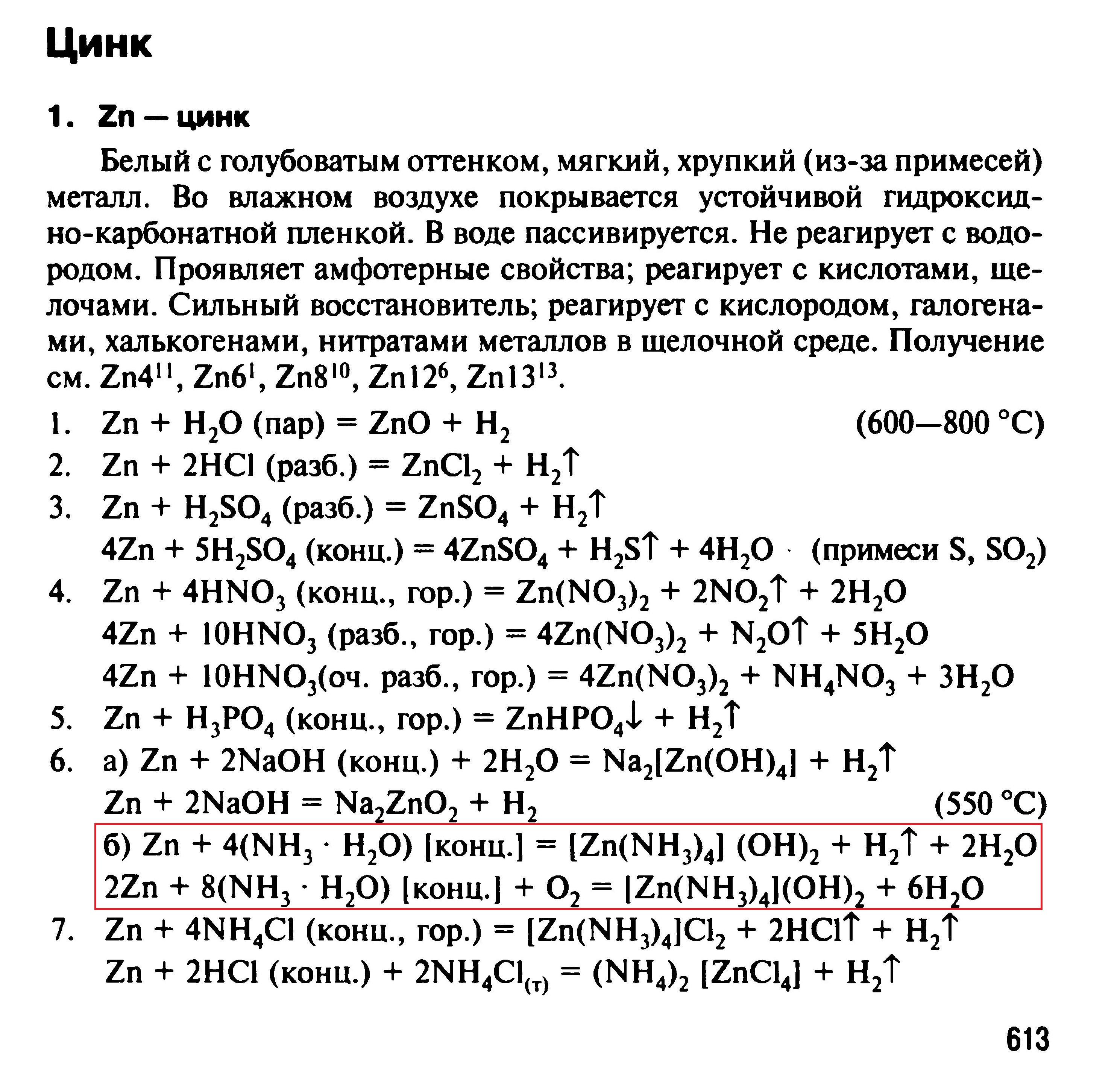

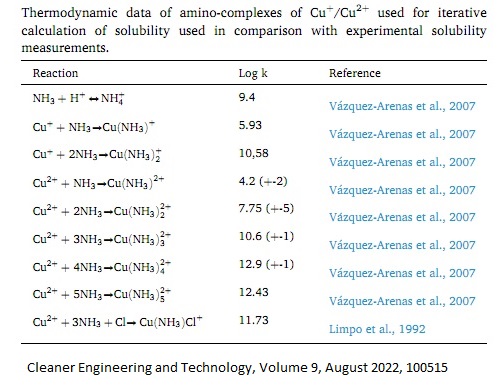

One of the most fascinating chemical experiments is the dissolution of copper metal in an aqueous solution of ammonia [1]. In the simplest version, copper wire or shavings are placed in a flask. Subsequently, a concentrated aqueous ammonia solution is added to completely cover the copper. There must be enough air above the surface of the solution. The flask is hermetically sealed. Цинк, аммиак и воздух (реакция металлического цинка с водным раствором аммиака и кислородом) Initially, the flask contains the colourless solution. Gradually, the solution turns dark blue due to the formation of the Cu(II) complex with ammonia molecules: Cu + 4NH3 + H2O + 0.5O2 = [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2 Oxygen acts as an oxidizing agent. After the oxygen inside the flask has entirely reacted, the solution, which contains the blue copper(II) complex [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2, will begin to discolour. The blue copper(II) complex reacts with metallic copper to form the colourless copper(I) complex [Cu(NH3)2](OH): [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2 + Cu = 2[Cu(NH3)2](OH) As a result, the solution will become colourless. As long as the flask is sealed, no further changes will occur. However, if the flask is opened, the colourless solution will gradually turn dark blue. This process can be speeded up by pouring the solution into another beaker or passing air through it. The fact is that the complex of monovalent copper with ammonia [Cu(NH3)2](OH) is easily oxidized by air to the corresponding complex of divalent copper [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2, which is coloured blue. 2[Cu(NH3)2](OH) + H2O + 0.5O2 + 4NH3 = 2[Cu(NH3)4](OH)2 Now, let us close the flask. Inside, there is the blue solution which will gradually discolour over time: [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2 + Cu = 2[Cu(NH3)2](OH) The flask can be opened again to allow air to enter, so the initially colourless solution will turn dark blue. The described cycle can be repeated many times (until one of the reactants is used up). There is another version of this experiment. Instead of a pure ammonia solution, the solution of a copper (II) salt with an excess of a concentrated ammonia solution is poured into a flask with copper metal. The vessel is hermetically sealed. The flask initially contains a dark blue solution of the divalent copper complex [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2, which gradually reacts with metallic copper, causing the solution to become discoloured. The further procedure is similar to that described above. This reaction can also be used for other types of chemical demonstrations. For instance, to remove a copper coating from steel products (coins, gun casings, etc.) [2].

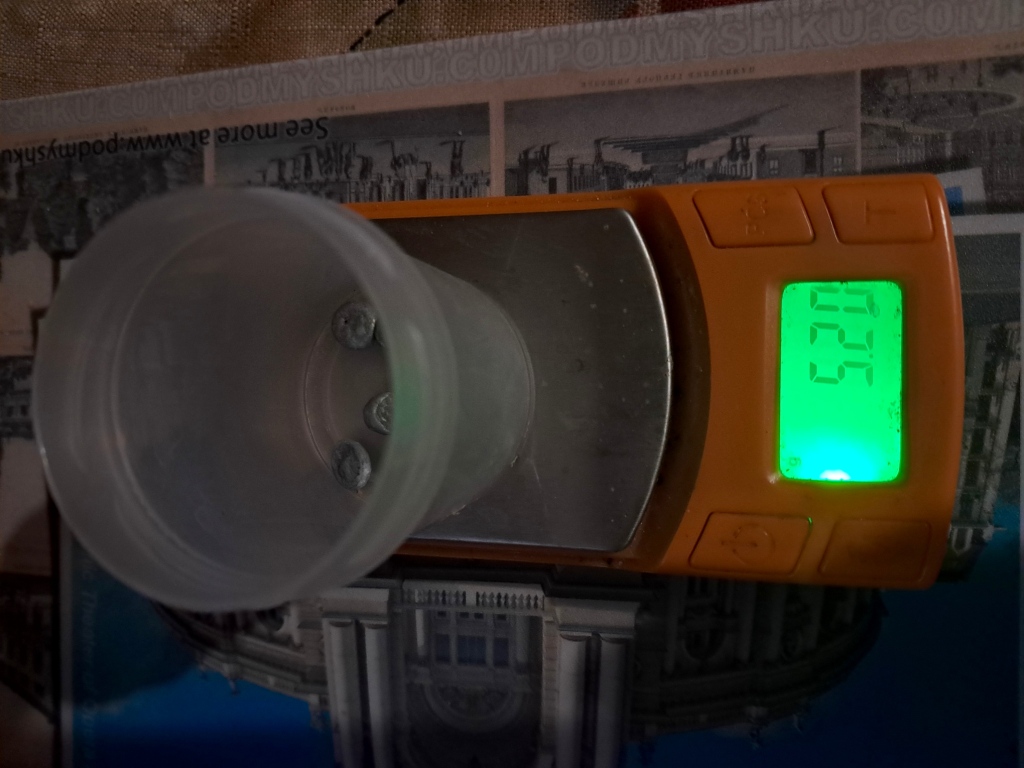

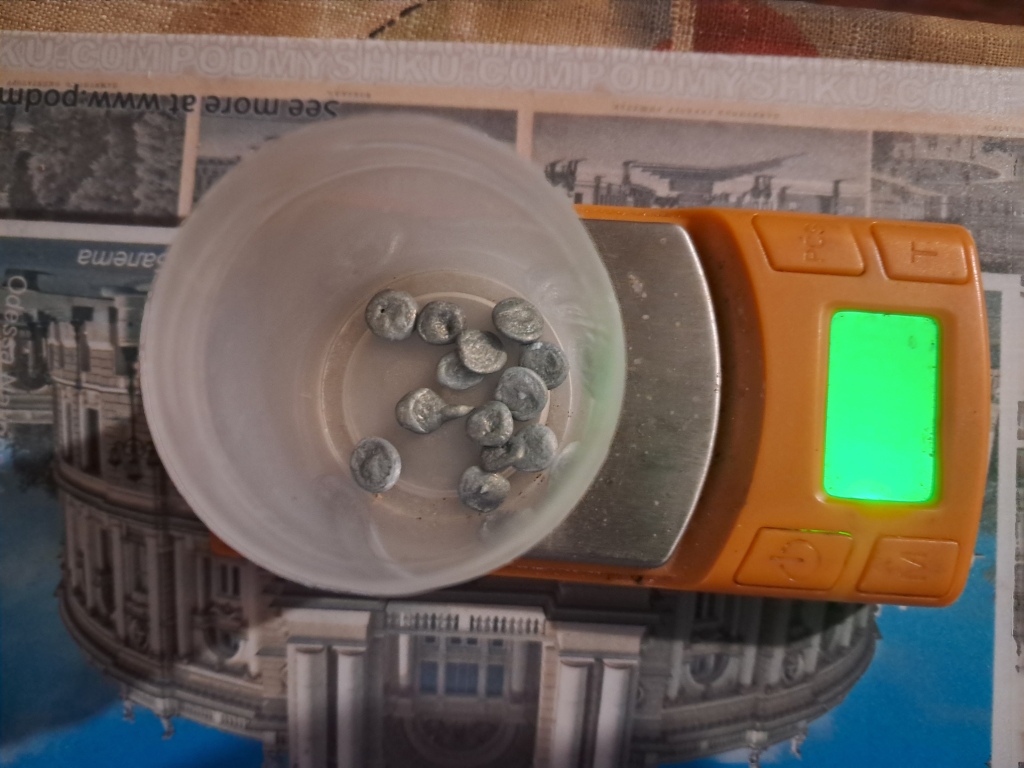

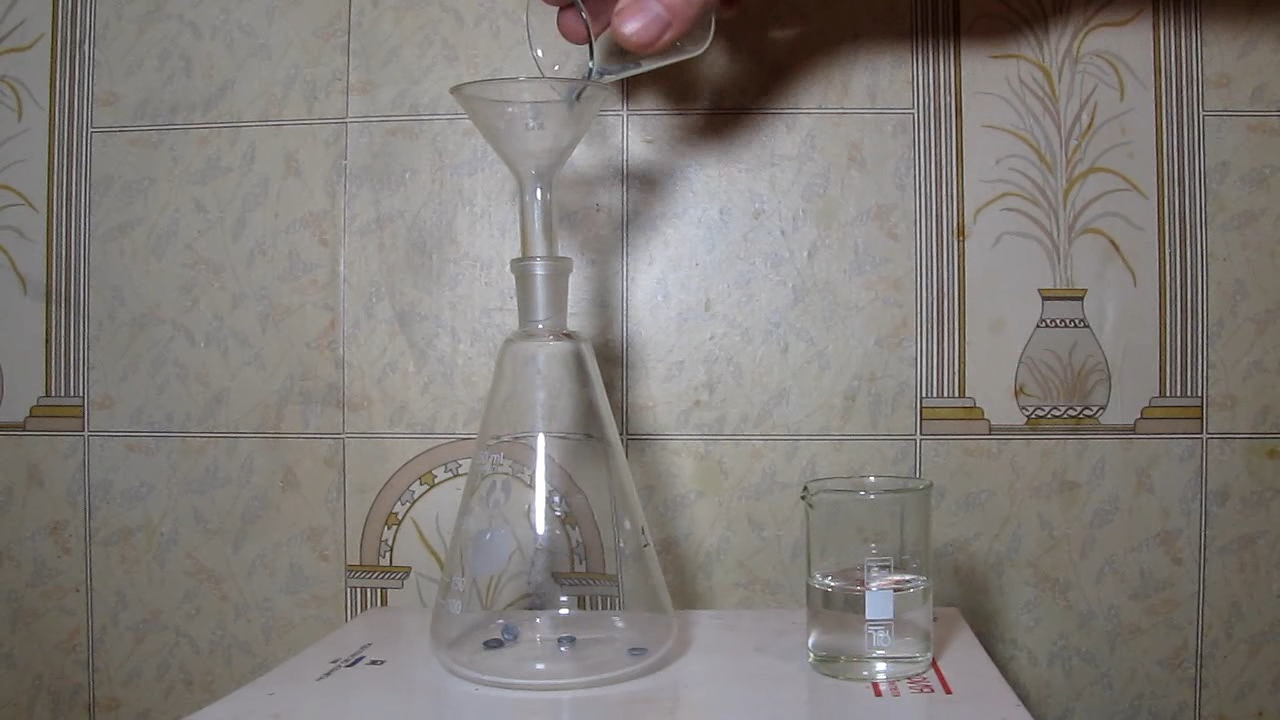

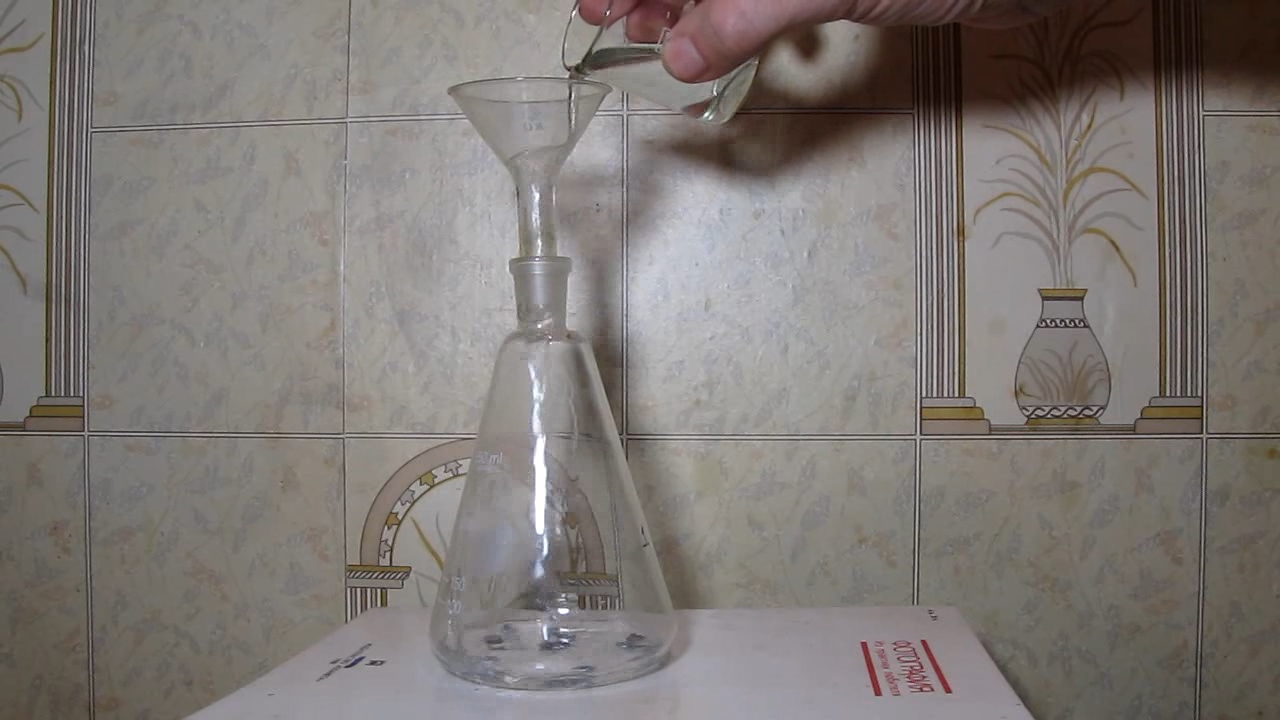

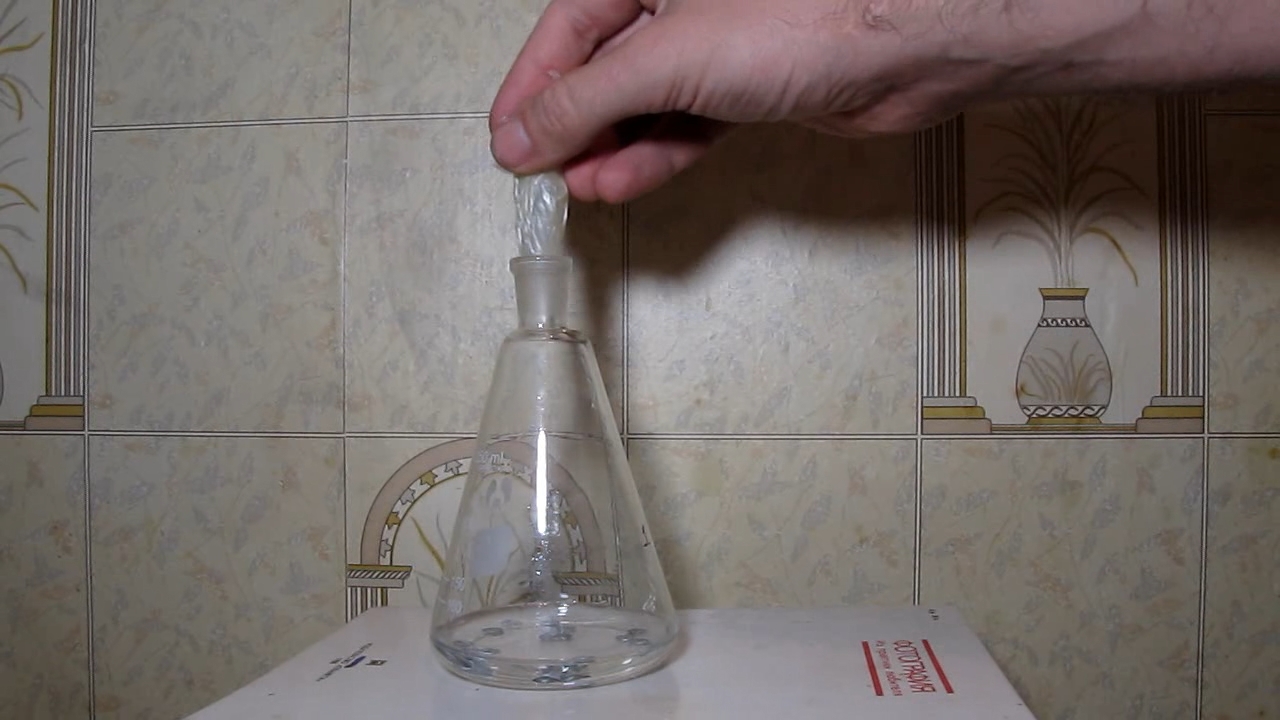

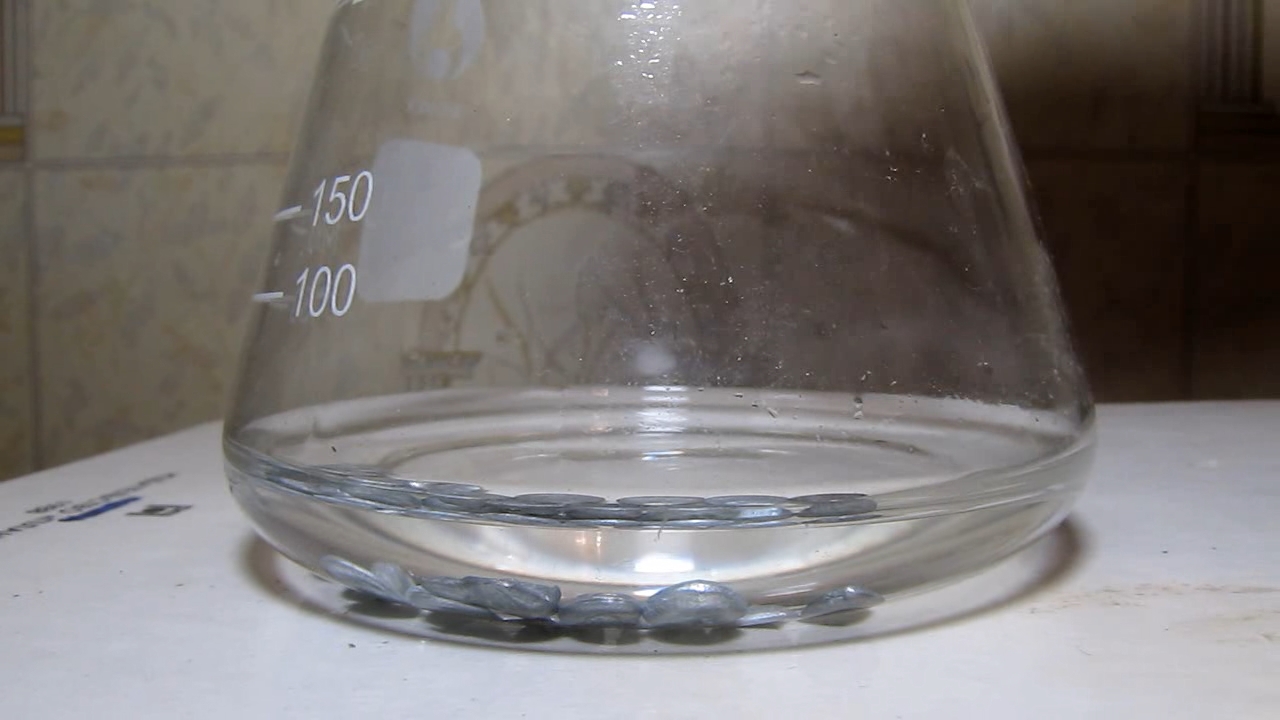

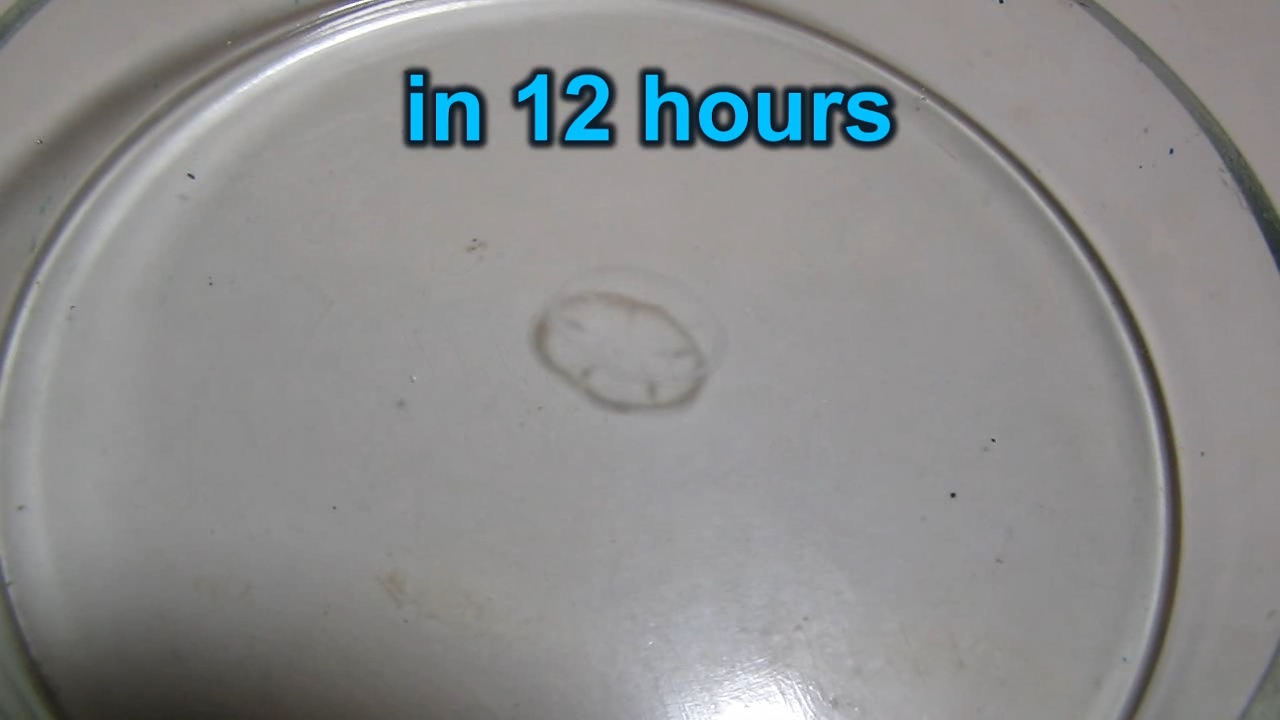

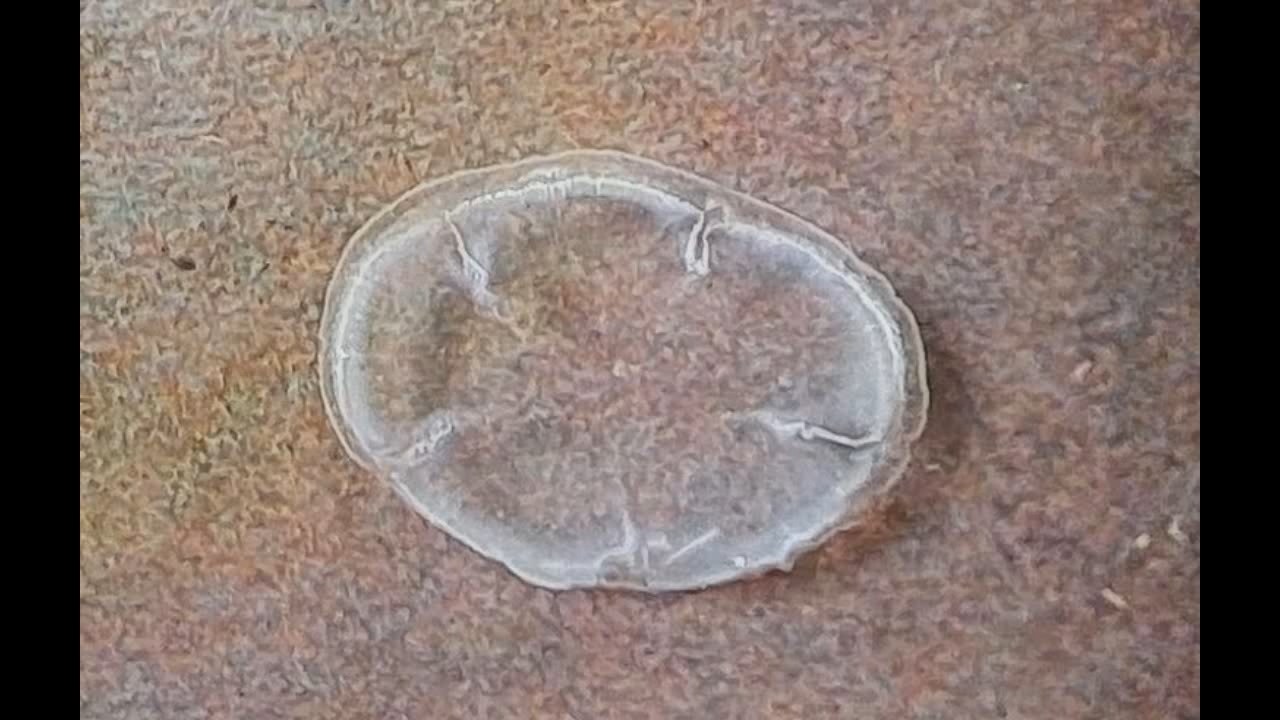

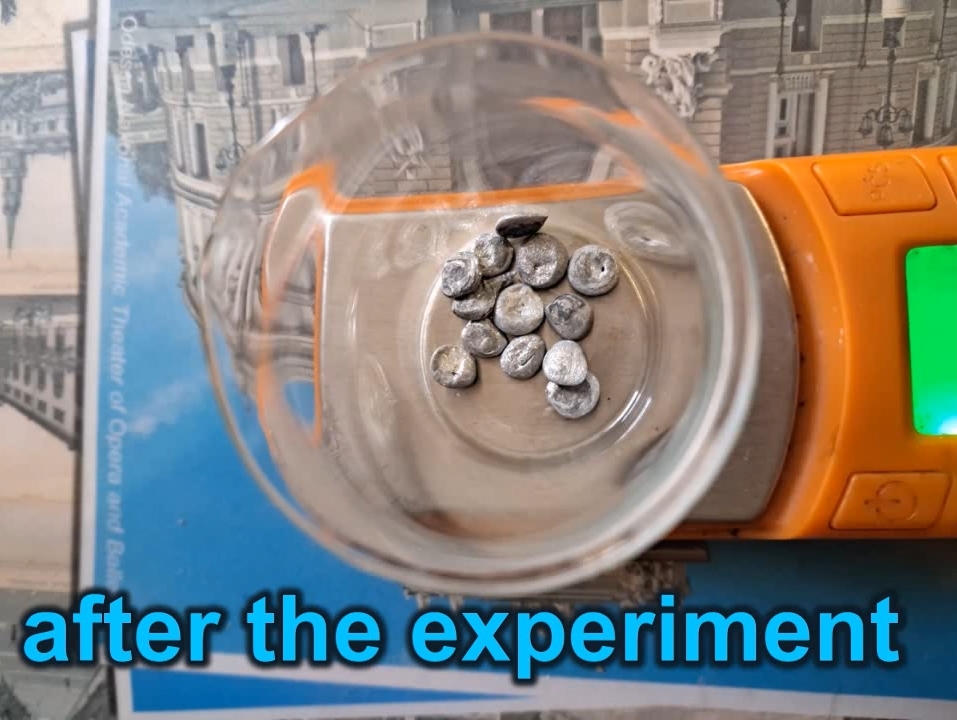

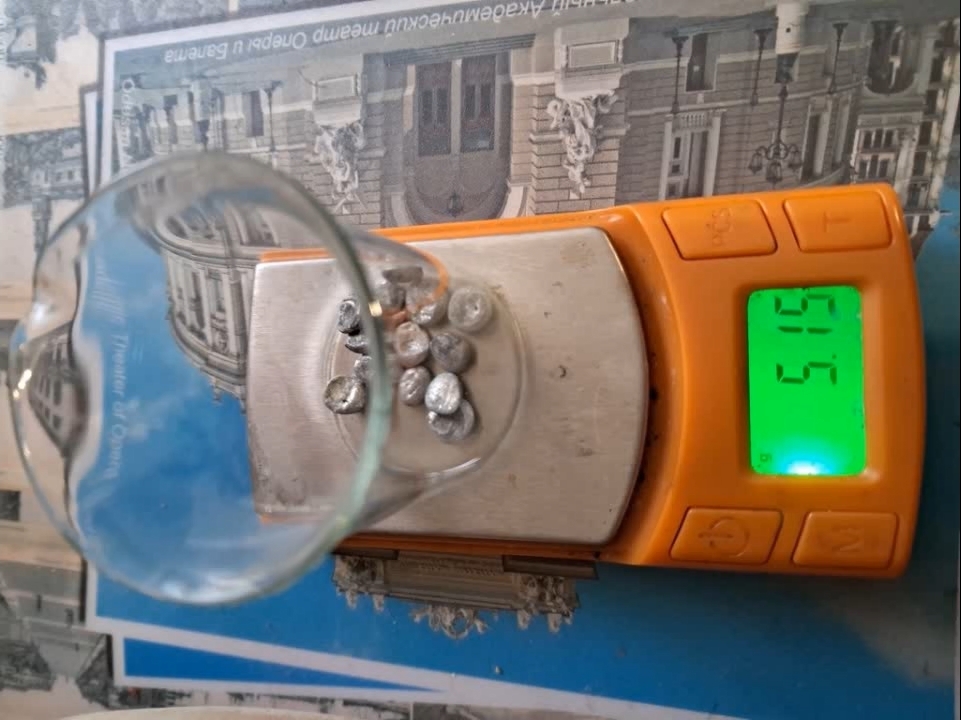

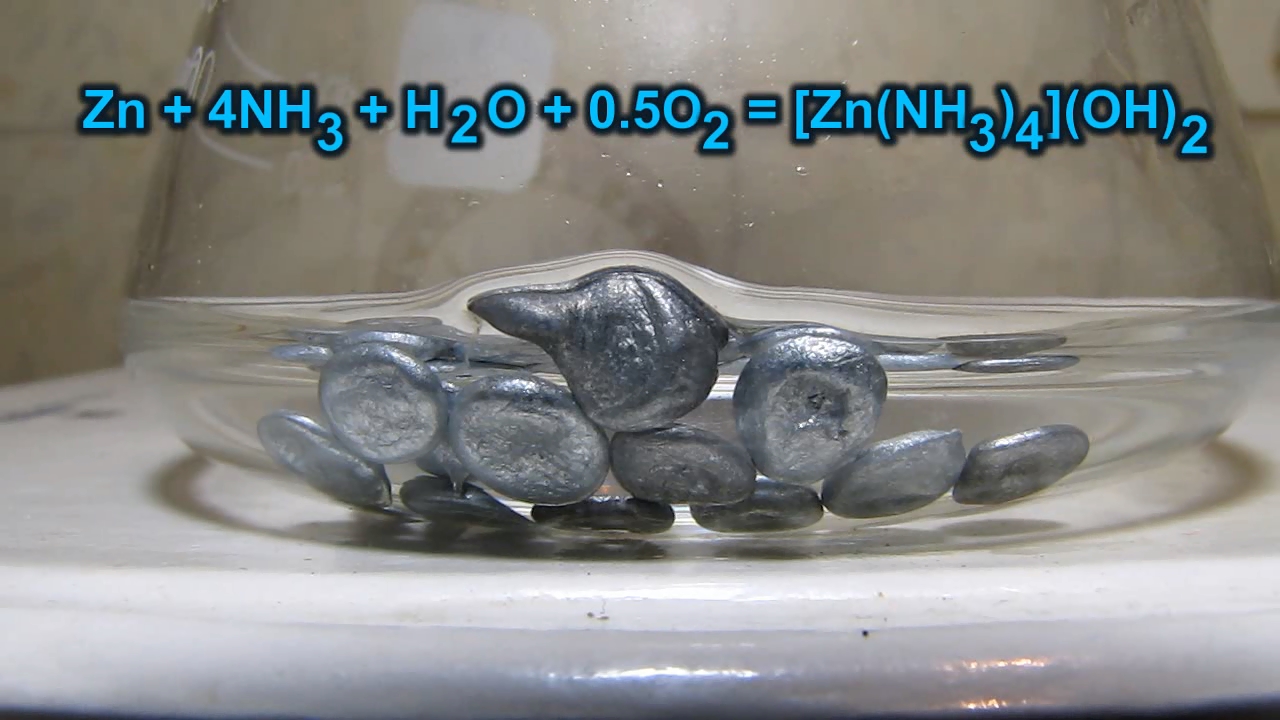

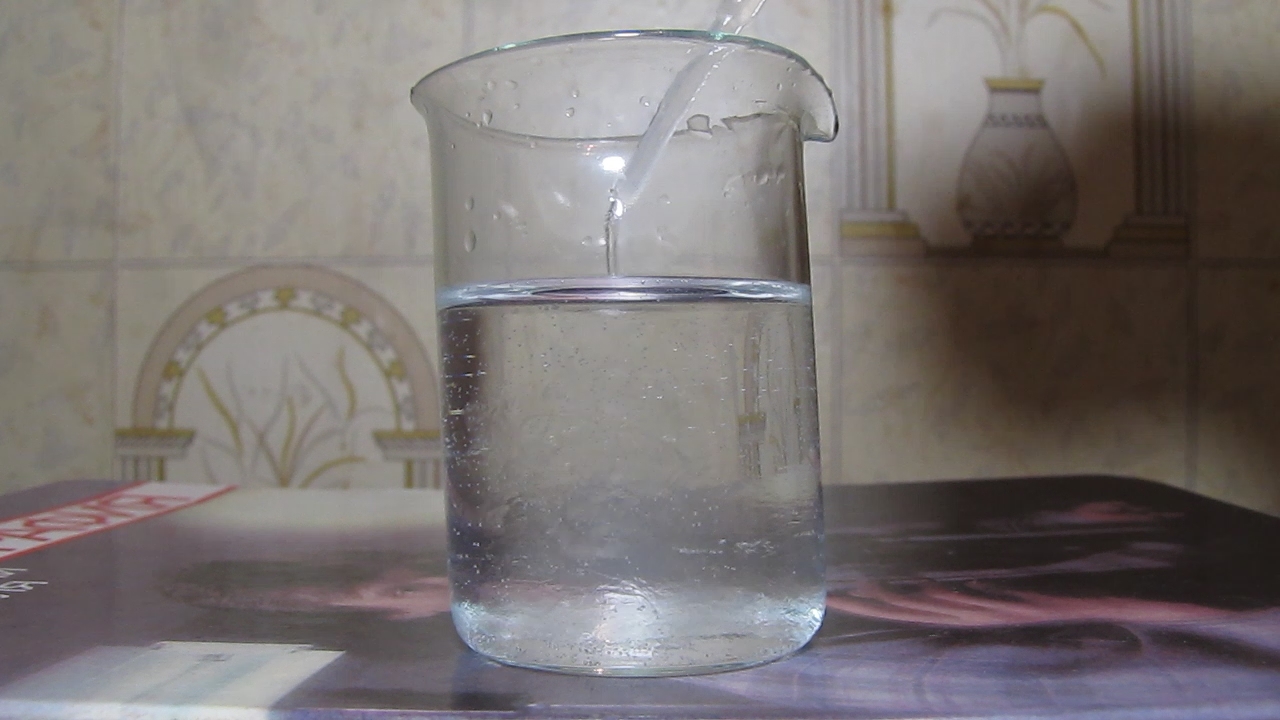

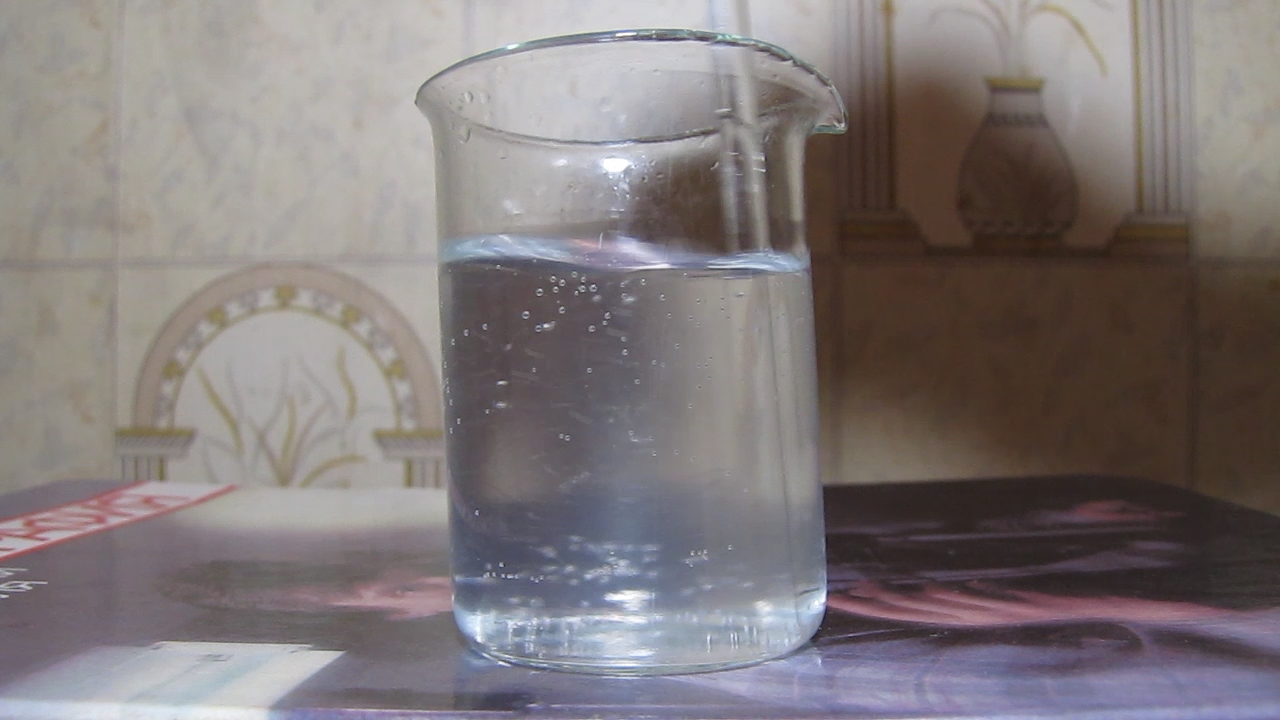

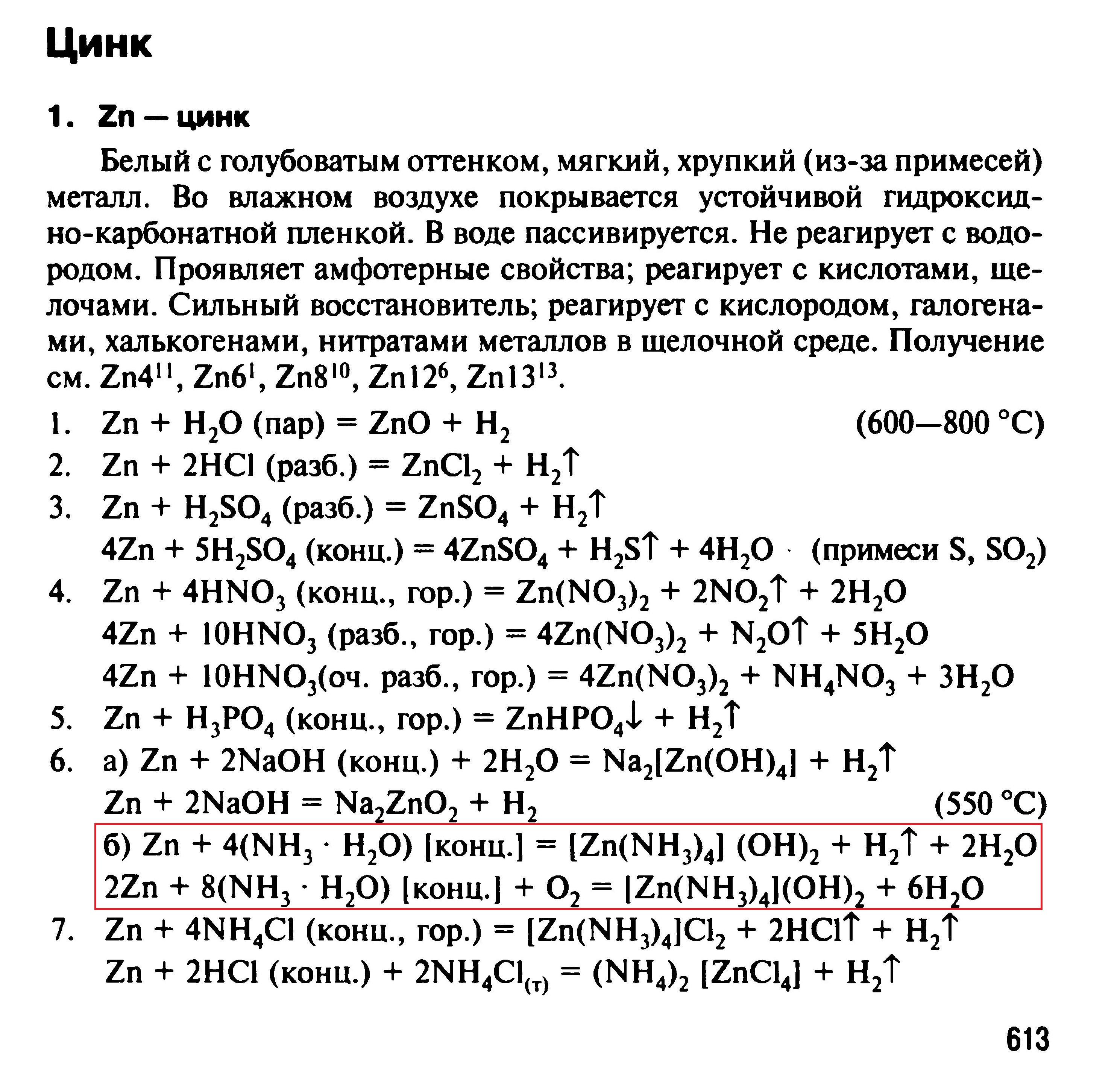

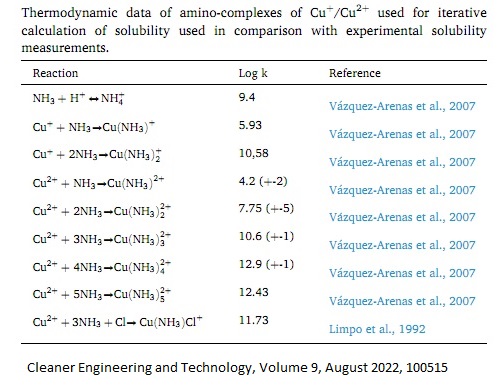

Why did I describe the reaction of ammonia and copper metal in such detail? The fact is that copper is far from the only metal that forms a strong complex with ammonia [3]. I immediately remembered zinc, then cobalt and nickel. I do not have cobalt metal; nickel is in stock, but I recalled about it later. Therefore, I decided to experiment with zinc. Zinc, similarly to copper, forms a complex with ammonia of the composition [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2. But there are also significant differences. Firstly, zinc, unlike copper, does not exhibit (+1) oxidation state in aqueous solutions. Secondly, the [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 complex is colourless. In other words, if we place metallic zinc and a concentrated aqueous solution of ammonia in a flask, the colour of the solution does not change, regardless of whether the formation reaction of [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 occurs or not. Zn + 4NH3 + H2O + 0.5O2 = [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 If this reaction takes place and the [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 complex is formed, then this complex will not react with metallic zinc to produce the hypothetical Zn(I) complex - "[Zn(NH3)2](OH)", since the latter compound does not exist. Let us start the experiment. I poured 30 ml of a concentrated ammonia solution into the flask and added 5.20 g of zinc metal. I closed the flask and left it standing. Once a day, I stirred the contents of the flask. Most of the internal volume of the flask was occupied by air. The flask stood for 10 days, and during this time, the appearance of the solution and zinc granules did not change. How can we determine whether the above reaction has occurred or not? There are several ways. First way. Take part of the solution from the flask, add acid in small portions and mix. Judging by analogy with the zinc-hydroxo complex - [Zn(OH)4]2-, when an acid is added to [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 complex, the precipitate of zinc hydroxide Zn(OH)2 should first form, which will then dissolve in the excess acid: [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 + 4H+ = Zn(OH)2 + 4NH4+ Zn(OH)2 + 2H+ = Zn2+ + 2H2O A little later, the second method came to my mind. It is much simpler and requires only a few drops of the test solution. If zinc has reacted with ammonia, water and oxygen, then the solution will contain the [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 complex, which is a single non-volatile substance in this solution. Therefore, instead of carrying out the described above reactions, it is enough to place a small portion of the solution on a glass and let it evaporate. If a white residue remains on the glass, it indicates the presence of the zinc complex with ammonia ligand [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 in the solution. So, I did. I dropped a drop of the solution into a Petri dish. By the next day, the solution dried out, and a white spot formed on the glass. This means the reaction of zinc, ammonia, oxygen and water occurred. The experiment could have been completed at this point, but I decided to further confirm the presence of the [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 complex in the solution using the first method given. I poured the entire solution from the flask with zinc into a glass and gradually began to add glacial acetic acid to it, stirring. White ammonium acetate smoke formed above the solution, but at first, nothing significant happened in the solution itself. Then, a white turbidity appeared in the liquid. Is it zinc hydroxide? However, further addition of acetic acid did not lead to the disappearance of the turbidity. The ammonia smell has disappeared. I checked the pH of the solution using a piece of indicator paper - it turned out to be about 5. But the turbidity did not disappear. As is known, zinc hydroxide easily dissolves in an excess of acetic acid. I had a seditious thought: perhaps the white substance is not zinc hydroxide. The white compound is an impurity dissolved in glacial acetic acid. When this acid was mixed with an aqueous ammonia solution, the dissolved compound precipitated as a distinct phase. Recently, I already had this happen: acetic acid, when diluted with water, gave a white cloudy solution. I then decided that the acid extracted impurities from the plastic of the bottle cap. Perhaps this acetic acid is also contaminated with compounds that are soluble in acetic acid but not soluble in water (by the way, both samples of acetic acid were given to me by the same person). A control test should be conducted to verify that the white cloudiness is not caused by impurities present in the added acetic acid. The control experiment is quite simple. I poured the acetic acid into another glass and added water to it. Familiar white turbidity appeared. At first, the turbidity of this solution was less intense than in the glass with the test solution (ammonia, water, ammonia zinc complex and acetic acid). But when I added more the acetic acid to the control beaker with the acetic acid and water, the intensity of the solution's turbidity in the two glasses became equal. Psychologically, it was very difficult, but I had to admit the obvious fact that the white particles were NOT zinc hydroxide but rather a compound contained in the acetic acid as an impurity. Why did no zinc hydroxide precipitate form? Was there no ammonia complex of zinc [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 in the solution? Does zinc not react with aqueous ammonia in the presence of oxygen? Fortunately, I quickly realized where I had gone wrong. I vaguely remembered that zinc hydroxide dissolves in aqueous solutions of ammonium salts. Not only in acids, alkalis and aqueous ammonia but also in ammonium salts! The reaction of acetic acid with ammonia produced ammonium acetate. CH3COOH + NH3 = CH3COONH4 + H2O Since zinc hydroxide is soluble in ammonium salts, it must not precipitate when the solution contains an excess of ammonium salts, such as ammonium acetate. I have looked in one monograph and one textbook on analytical chemistry - this is true: zinc hydroxide dissolves in ammonium salts. Thus, the first method was initially erroneous. It is okay, "You learn from your mistakes." But there is also a third way: I weighed the zinc granules BEFORE the experiment. After the reaction, I washed the granules with distilled water, dried and weighed them again. The initial mass was 5.20 g, the final mass was 5.15 g, the difference was 0.05 g. This is not enough. If I had had an analytical balance that allowed me to weigh with an accuracy of 0.0001 g, this result would have satisfied me, but the accuracy of my scales is 0.01 g. Doubts struck: perhaps the first method (evaporation of drops of solution on glass) is also incorrect. What if there were dissolved impurities in the original ammonia solution that gave a white residue on the glass? This could be easily verified by evaporating a few drops of the original ammonia solution on a glass surface. That is to conduct a blank test. If the ammonia is pure, there is no significant solid residue after it evaporates. Unfortunately, I had already added another ammonia solution from another batch to the bottle with the ammonia solution (which was used for the experiment) since there was not enough of the first solution in the bottle. At first, the situation puzzled me, and I decided to repeat the experiment. However, then I realized that not everything is so bad. It was necessary to evaporate the mixture of two ammonia solutions on a glass surface; this mixture was currently in the bottle. If a significant amount of solid residue forms, one of the two solutions is contaminated (or both solutions are impure). But if there is practically no solid residue, it means that both ammonia solutions are clean. I carried out the test: after the solution was evaporated, a white residue formed, but its amount was very small (the solid substance was barely noticeable on the glass). Thus, both ammonia solutions were pure. My doubts disappeared: part of the metallic zinc dissolved when interacting with an aqueous ammonia solution and air. I looked in the reference book [4]. It turns out that zinc metal reacts with ammonia solution not only in the presence of air but also under anaerobic (oxygen-free) conditions. Moreover, zinc metal dissolves in a hot ammonium chloride solution:  1 See the article Oxidation of copper (I) ammonia complex [Cu(NH3)2]OH with atmospheric oxygen / Окисление аммиаката меди (I) [Cu(NH3)2]OH кислородом воздуха [link]. 2 See the article Cartridge case, copper, ammonia and oxygen / Винтовочная гильза, медь, аммиак и кислород [link]. 3 Copper forms not a single but several complexes with ammonia (which are in equilibrium with each other).  4 Реакции неорганических веществ: справочник / Р. А. Лидин, В. А. Молочко, Л. Л. Андреева; под ред. Р. А. Лидина. - 2-е изд., перераб. и доп. - М.: Дрофа, 2007 [link]. | ||||||||

Zinc, ammonia and air (reaction of zinc metal with aqueous ammonia and oxygen) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The evaporation of the obtained solution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The mass of the zinc after the reaction |

|

|

I added glacial acetic acid to the obtained solution. The turbidity appeared due to impurity which was in the acetic acid |

|

|

|

|

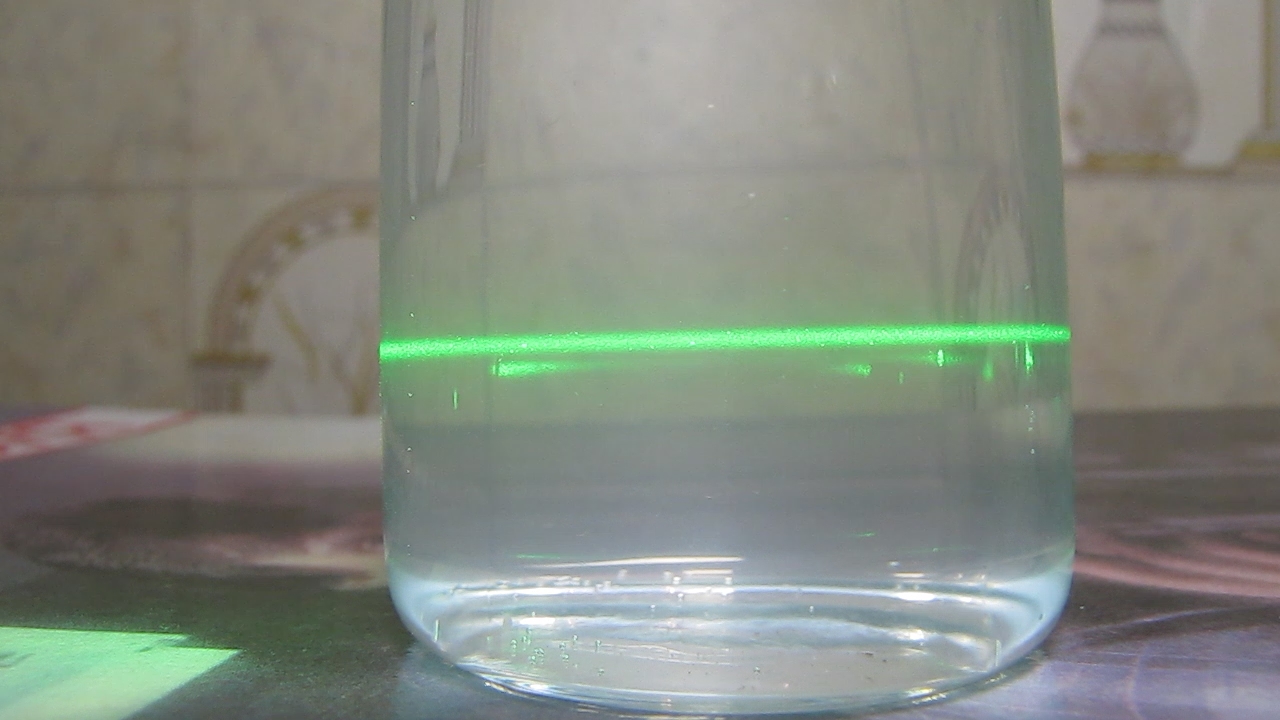

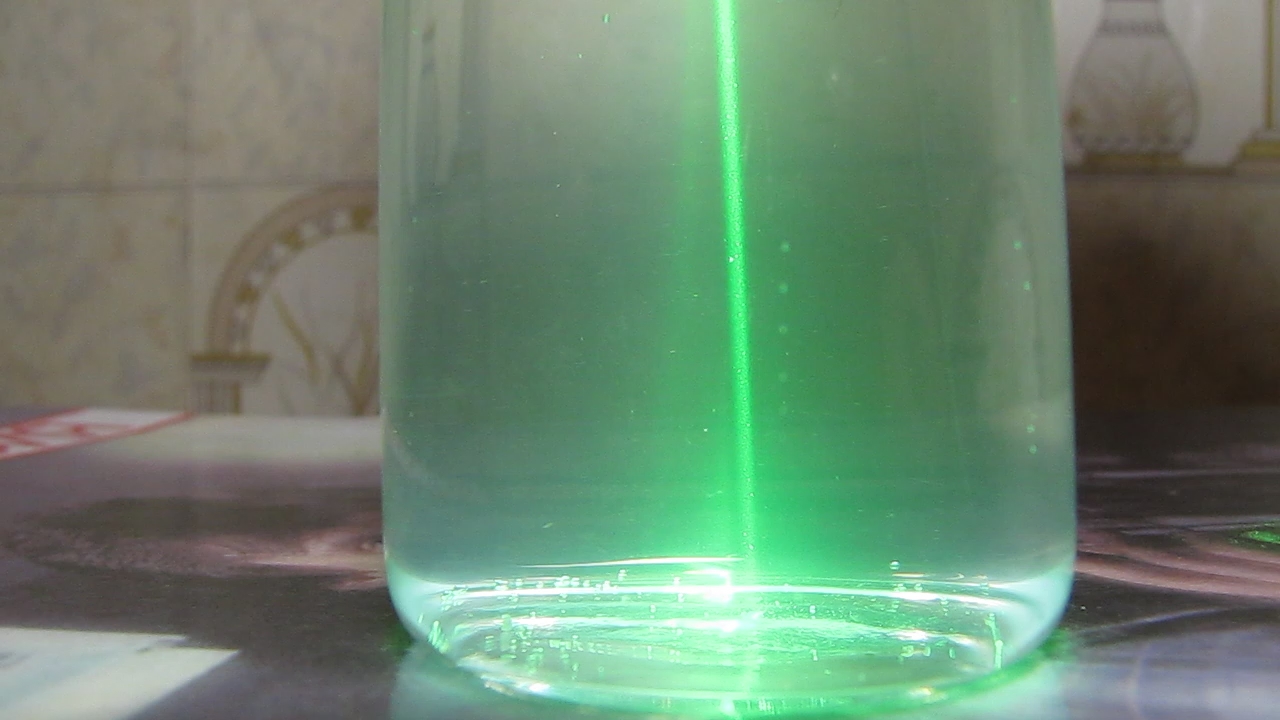

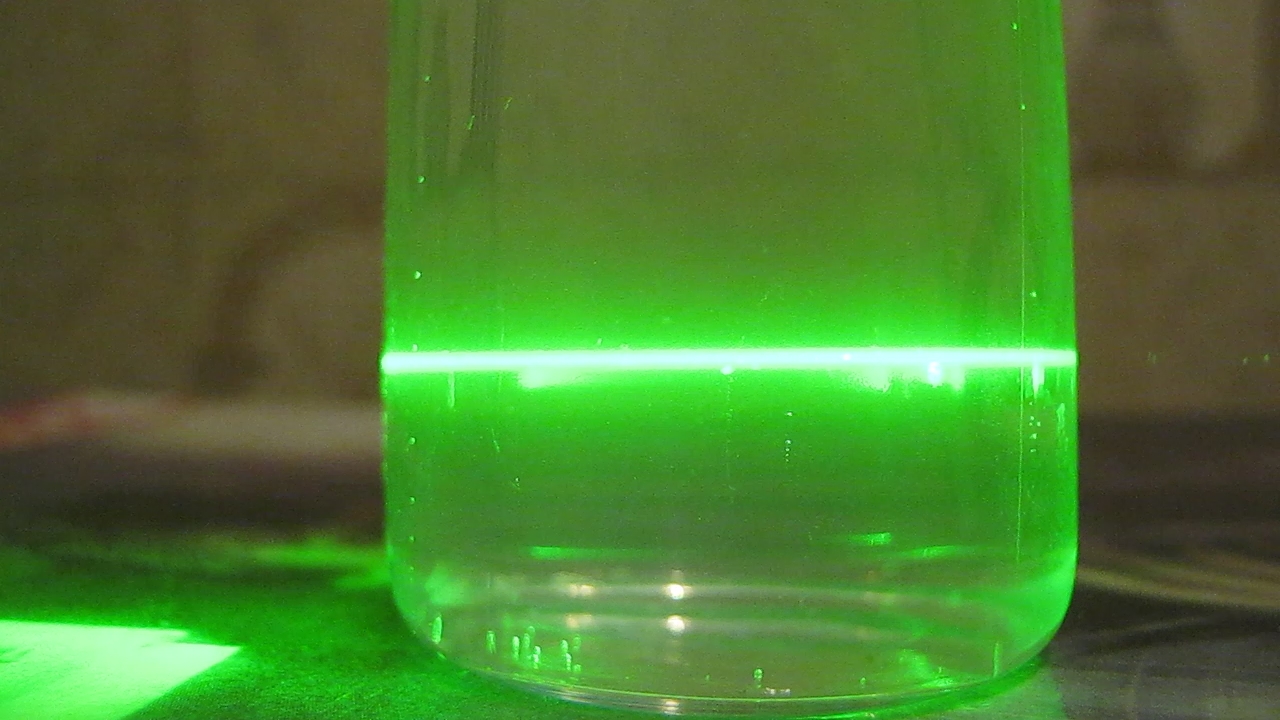

The Tyndall effect in the solution |

|

|

|

|

Цинк, аммиак и воздух (реакция металлического цинка с водным раствором аммиака и кислородом)

Один из самых интересных химических экспериментов - растворение металлической меди в водном растворе аммиака [1]. В самом простом варианте в колбу помещают медную проволоку или медные стружки и заливают их концентрированным водным раствором аммиака (чтобы раствор полностью покрыл медь). Над поверхностью раствора должно находиться достаточно воздуха. Колбу герметично закрывают. Первоначально в колбе находится бесцветный раствор. Постепенно раствор становится темно-синим за счет образования комплекса Cu(II) с молекулами аммиака: Cu + 4NH3 + H2O + 0.5O2 = [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2 Окислителем выступает кислород. После того, как весь кислород внутри колбы израсходовался на реакцию, раствор начинает обесцвечиваться. Синий комплекс меди (II) [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2 реагирует с металлической медью, образуя бесцветный комплекс меди (I) [Cu(NH3)2](OH): [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2 + Cu = 2[Cu(NH3)2](OH) В результате раствор станет бесцветным. Пока колба герметично закрыта, дальнейших изменений происходить не будет. Но, если колбу открыть, бесцветный раствор постепенно станет темно-синим. Этот процесс можно ускорить, если перелить раствор в другую емкость или пропустить сквозь него воздух. Дело в том, что комплекс одновалентной меди и аммиака [Cu(NH3)2](OH) легко окисляется воздухом до соответствующего комплекса двухвалентной меди [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2, который окрашен в синий цвет. 2[Cu(NH3)2](OH) + H2O + 0.5O2 + 4NH3 = 2[Cu(NH3)4](OH)2 Теперь закроем колбу. Внутри колбы содержится синий раствор, который при стоянии постепенно обесцветится: [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2 + Cu = 2[Cu(NH3)2](OH) Колбу можно снова открыть, чтобы впустить в нее воздух - бесцветный раствор станет темно-синим. Описанный цикл можно повторять много раз (пока не израсходуется один из реагентов). В другом варианте этого эксперимента в колбу с металлической медью наливают не чистый раствор аммиака, а раствор соли меди (II) с избытком концентрированного раствора аммиака. Колбу герметично закрывают. Первоначально в колбе содержится темно-синий раствор комплекса двухвалентной меди [Cu(NH3)4](OH)2, который постепенно реагирует с металлической медью, в результате чего раствор обесцвечивается. Дальше - аналогично описанному выше. Данную реакцию также можно использовать для химических демонстраций другого типа. А именно - для снятия медного покрытия со стальных изделий (монеты, ружейные гильзы и т.д.) [2]. Почему я так детально описал реакцию аммиака и металлической меди? Дело в том, что медь - далеко не единственный металл, который образует прочный комплекс с аммиаком [3]. Я сразу вспомнил цинк, потом - кобальт и никель. Металлического кобальта у меня нет, никель - есть в наличии, но я вспомнил о нем позже. Поэтому решил поэкспериментировать с цинком. Цинк аналогично меди образует комплекс с аммиаком состава [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2. Но есть и существенные различия. Во-первых, цинк в отличие от меди не проявляет в водных растворах степени окисления (+1). Во-вторых, комплекс [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 бесцветен. Другими словами, если мы поместим в колбу металлический цинк и концентрированный водный раствор аммиака, то окраска раствора не изменится независимо от того, будет протекать реакция образования [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2, или нет. Zn + 4NH3 + H2O + 0.5O2 = [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 Если эта реакция будет иметь место и образуется комплекс [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2, то данный комплекс не будет реагировать с металлическим цинком с образованием гипотетического комплекса Zn(I) - "[Zn(NH3)2](OH)", поскольку последнее соединение не существует. Приступим к эксперименту. Я налил в колбу 30 мл концентрированного раствора аммиака, добавил 5.20 г металлического цинка. Колбу закрыл и оставил стоять. Один раз на день перемешивал содержимое колбы. Большую часть внутреннего объема колбы занимал воздух. Колба простояла 10 дней, за это время внешний вид раствора и гранул цинка не изменился. Как определить, произошла приведенная выше реакция или нет? Существует несколько способов. Первый способ. Отобрать из колбы часть раствора и небольшими порциями добавлять к нему кислоту, перемешивать. Если судить по аналогии с гидроксокомплексом цинка - [Zn(OH)4]2-, при добавлении кислоты к [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 сначала должен выпасть осадок гидроксида цинка Zn(OH)2, который потом растворится в избытке кислоты: [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 + 4H+ = Zn(OH)2 + 4NH4+ Zn(OH)2 + 2H+ = Zn2+ + 2H2O Чуть позже мне пришел в голову второй способ. Он гораздо проще и требует буквально несколько капель исследуемого раствора. Если цинк прореагировал с аммиаком, водой и кислородом, то в растворе находится комплекс [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2, который является единым нелетучим веществом в данном растворе. Следовательно, вместо того чтобы проводить приведенные выше реакции достаточно поместить небольшую порцию раствора на стекло и дать ей испариться. Если на стекле останется белый осадок (остаток), значит раствор содержит аммиачный комплекс цинка [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2. Так и сделал. Капнул одну каплю раствора в чашку Петри. На следующий день раствор высох, на стекле образовалось белое пятно. Значит, реакция цинка, аммиака, кислорода и воды имела место. На этом эксперимент можно было закончить, но я решил дополнительно подтвердить наличие в растворе комплекса [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2 первым приведенным способом. Из колбы с цинком вылил весь раствор в стакан и постепенно стал добавлять к нему ледяную уксусную кислоту, перемешивал. Над раствором образовался белый дым ацетата аммония, но сначала в самом растворе ничего существенного не происходило. Затем в жидкости появилась белая муть. Это гидроксид цинка? Но дальнейшее добавление уксусной кислоты не привело к исчезновению мути. Запах аммиака исчез. Я проверил pH раствора с помощью индикаторной бумажки - оказалось около 5. Но муть не исчезала. Как известно, гидроксид цинка легко растворяется в избытке уксусной кислоты. Возникла у меня крамольная мысль: возможно, белая муть - не гидроксид цинка. Белое вещество - примесь, которая была растворена в ледяной уксусной кислоте, а потом выделилась в твердую фазу при смешивании этой кислоты с водным раствором аммиака. Недавно у меня такое уже было: уксусная кислота при разбавлении водой дала белую муть. Тогда я решил, что кислота экстрагировала вещества из пластика крышки бутылки. Возможно, данная уксусная кислота тоже загрязнена примесями, которые растворимы в уксусной кислоте, но не растворимы в воде (кстати, оба образца уксусной кислоты мне дал один и тот же человек). Необходимо провести контрольный тест, чтобы убедиться, что белая муть не является результатом того, что добавленная уксусная кислота содержала примеси. Контрольный опыт очень простой. Налил в другой стакан уксусную кислоту и добавил к ней воду. Возникла знакомая белая муть. Сначала мутность данного раствора была менее интенсивной, чем в стакане с исследуемым раствором (аммиак, вода, аммиачный комплекс цинка и уксусная кислота). Но когда я добавил больше уксусной кислоты в контрольный стакан с уксусной кислотой и водой, интенсивность помутнения раствора в двух стаканах сравнялась. Психологически это было очень трудно, но пришлось признать очевидный факт, что белые частицы - НЕ гидроксид цинка, а вещество, которое содержится в качестве примеси в уксусной кислоте. Почему осадок гидроксида цинка НЕ образовался? Неужели в растворе не было аммиачного комплекса цинка, [Zn(NH3)4](OH)2? Цинк не реагирует с водным раствором аммиака в присутствии кислорода? К счастью, я быстро понял, где я ошибся. Я смутно вспомнил, что гидроксид цинка растворяется в водных растворах солей аммония. Не только в кислотах, щелочах и водном аммиаке, но и в солях аммония! При реакции уксусной кислоты с аммиаком образовался ацетат аммония. CH3COOH + NH3 = CH3COONH4 + H2O Поскольку гидроксид цинка растворяется в солях аммония, он не должен выпадать в осадок, когда в растворе содержится избыток солей аммония, например, ацетата аммония. Посмотрел одну монографию и один учебник по аналитической химии - так и есть: гидроксид цинка растворяется в солях аммония. Таком образом, первый способ был изначально ошибочным. Ничего, "на ашипках учаться". Но есть еще и третий способ: я взвесил гранулы цинка ДО эксперимента. После поведения реакции я промыл гранулы дистиллированной водой, высушил и снова взвесил. Первоначальная масса была 5.20 г, конечная 5.15 г, разница - 0.05 г. Это мало. Были бы у меня аналитические весы, которые позволяют взвешивать с точностью до 0.0001 г - такой результат меня бы удовлетворил, но точность моих весов - 0.01 г. Вонзили сомнения: возможно первый способ (испарение капель раствора на стекле) тоже некорректный. А вдруг в исходном растворе аммиака были растворенные примеси, которые дали белый осадок на стекле? Это можно было легко проверить, испарив несколько капель исходного раствора аммиака на стекле. Т.е., провести холостую пробу. Если аммиак чистый, после его испарения не должно быть существенного твердого остатка. К сожалению, в бутылку с раствором аммиака (который был использован для эксперимента) я уже долил другой раствор аммиака из другой партии, поскольку первого раствора в бутылке было мало. Сначала ситуация поставила меня в тупик, и я решил повторить эксперимент. Но потом понял, что не все так плохо. Нужно испарить на стекле смесь двух растворов аммиака, которая теперь находилась в бутылке. Если образуется существенное количество твердого остатка, значит один из двух растворов был загрязнен (или оба раствора были "химически нечистыми"). Но если твердого остатка практически не будет, значит, оба раствора аммиака были чистыми. Провел тест: после упаривания раствора белый остаток образовался, но его оказалось очень мало (твердое вещество было едва заметно на стекле). Таким образом, оба раствора аммиака были достаточно чистыми. Сомнения исчезли: часть металлического цинка растворилась при взаимодействии с водным раствором аммиака и воздухом. Посмотрел справочник [4]. Оказывается, что металлический цинк реагирует с раствором аммиака не только в присутствии воздуха, но и в анаэробных условиях. Более того, металлический цинк растворяется в горячем растворе хлорида аммония:  1 See the article Oxidation of copper (I) ammonia complex [Cu(NH3)2]OH with atmospheric oxygen / Окисление аммиаката меди (I) [Cu(NH3)2]OH кислородом воздуха [link]. 2 See the article Cartridge case, copper, ammonia and oxygen / Винтовочная гильза, медь, аммиак и кислород [link]. 3 Медь образует не один, а сразу несколько комплексов с аммиаком (которые находятся между собой в равновесии).  4 Реакции неорганических веществ: справочник / Р. А. Лидин, В. А. Молочко, Л. Л. Андреева; под ред. Р. А. Лидина. - 2-е изд., перераб. и доп. - М.: Дрофа, 2007 [link]. |