Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2024

Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts

| Content | Chemistry experiments - video | Physics experiments - video | Home Page - Chemistry and Chemists |

|

Chemistry and Chemists № 1 2024 Journal of Chemists-Enthusiasts |

Vegetable oils, ammonia and 'inverted' lava lamp - pt.1, 2 V.M. Viter |

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

Sunflower oil and ammonia solution - part 1

During experiments to obtain emulsions from vegetable oil, I remembered the 'lava lamp'. It is a decorative lamp invented in the 1960s. The lamp has a transparent body filled with two immiscible liquids. These liquids have close but not equal densities. The upper liquid is transparent and colourless or slightly coloured. Below it is another slightly heavier liquid, which is brightly coloured. When the lava lamp is turned on, the bottom layer is heated by the incandescent lamp located underneath it, so the density of the bottom liquid decreases. As a result, the lower liquid becomes less dense than the upper one and floats up as bright, large drops, creating bizarre shapes in the lamp's light. At the top of the reservoir, these drops cool; therefore, their density becomes higher than the density of the surrounding ('upper') liquid, after which the drops sink to the bottom, where they heat up again. Ordinary convection occurs, which causes the appearance of an 'art object'.

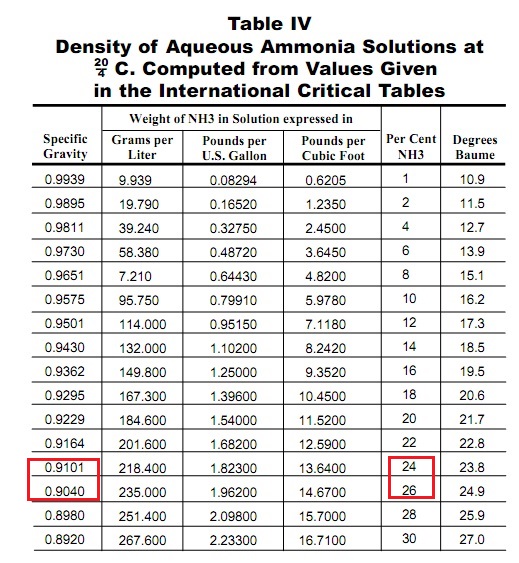

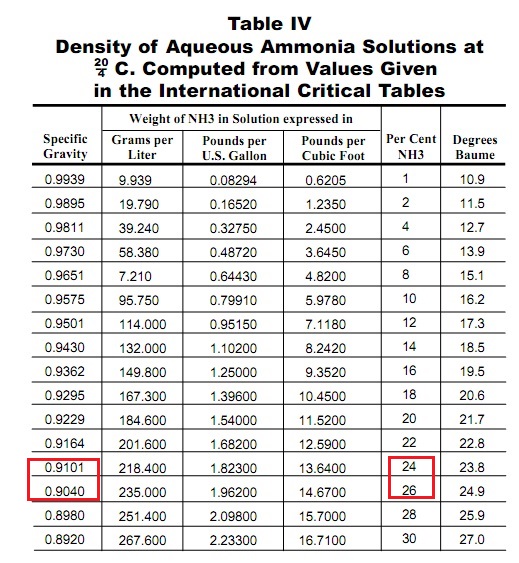

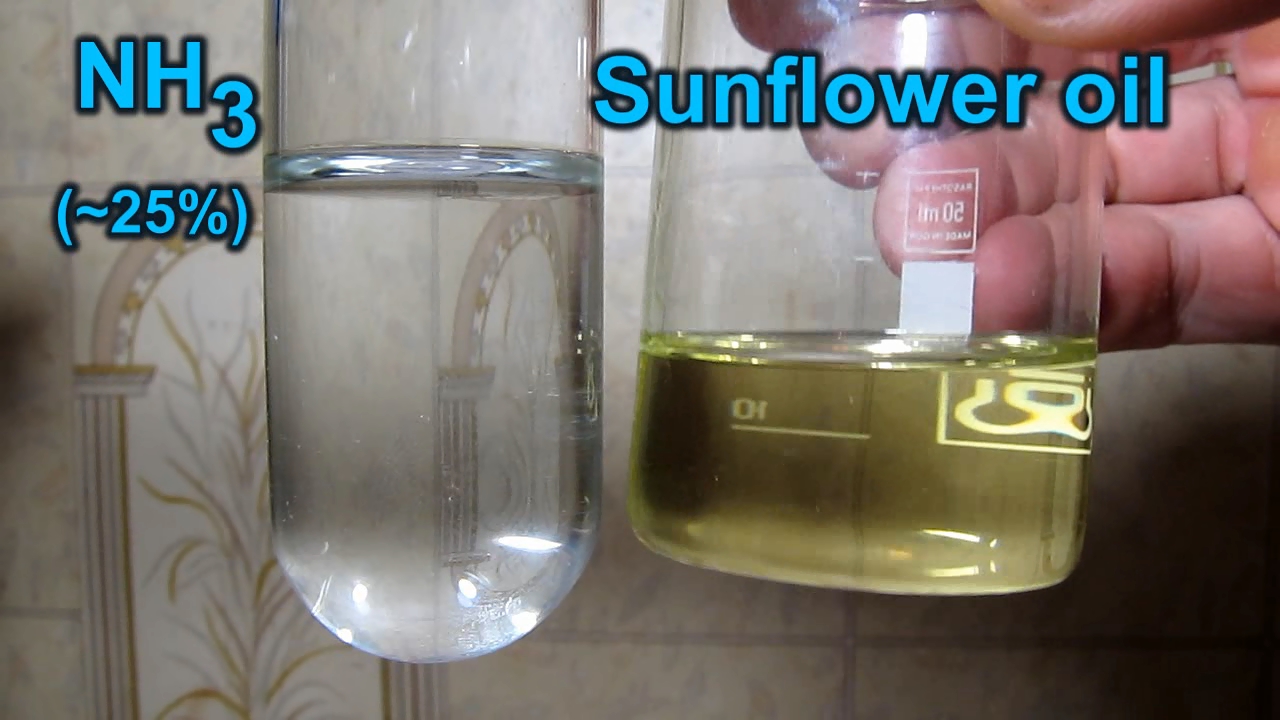

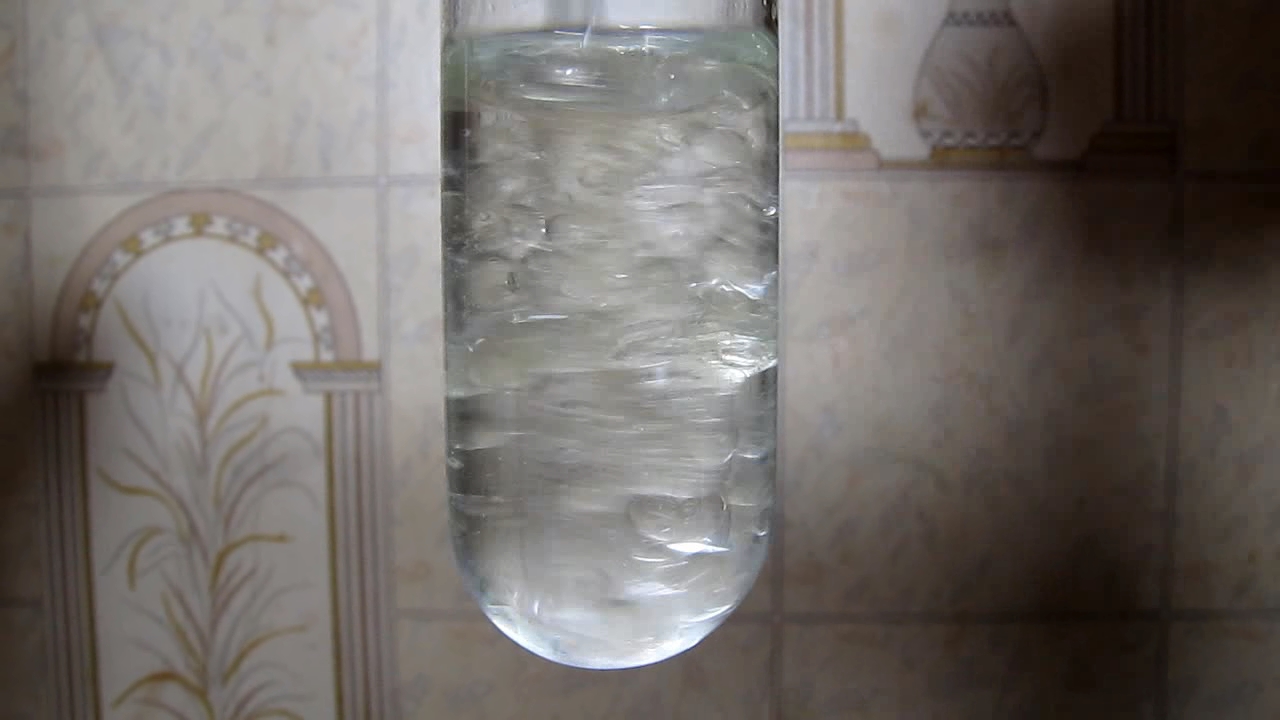

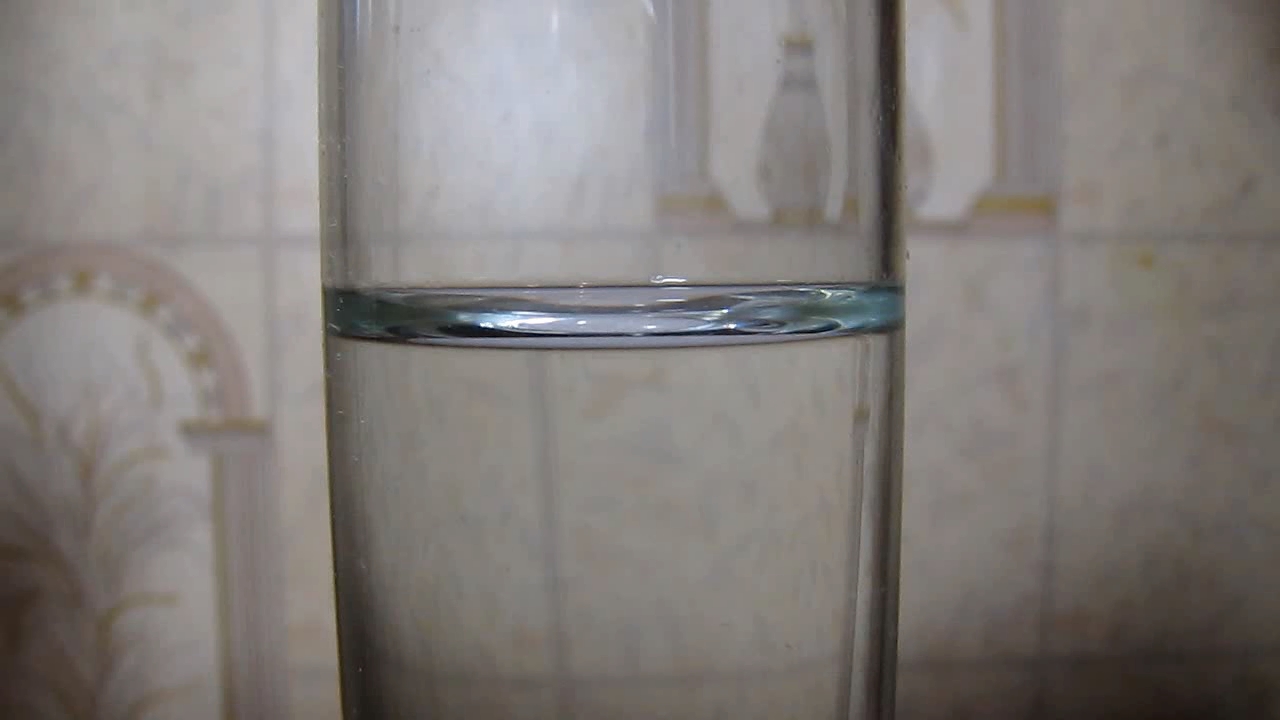

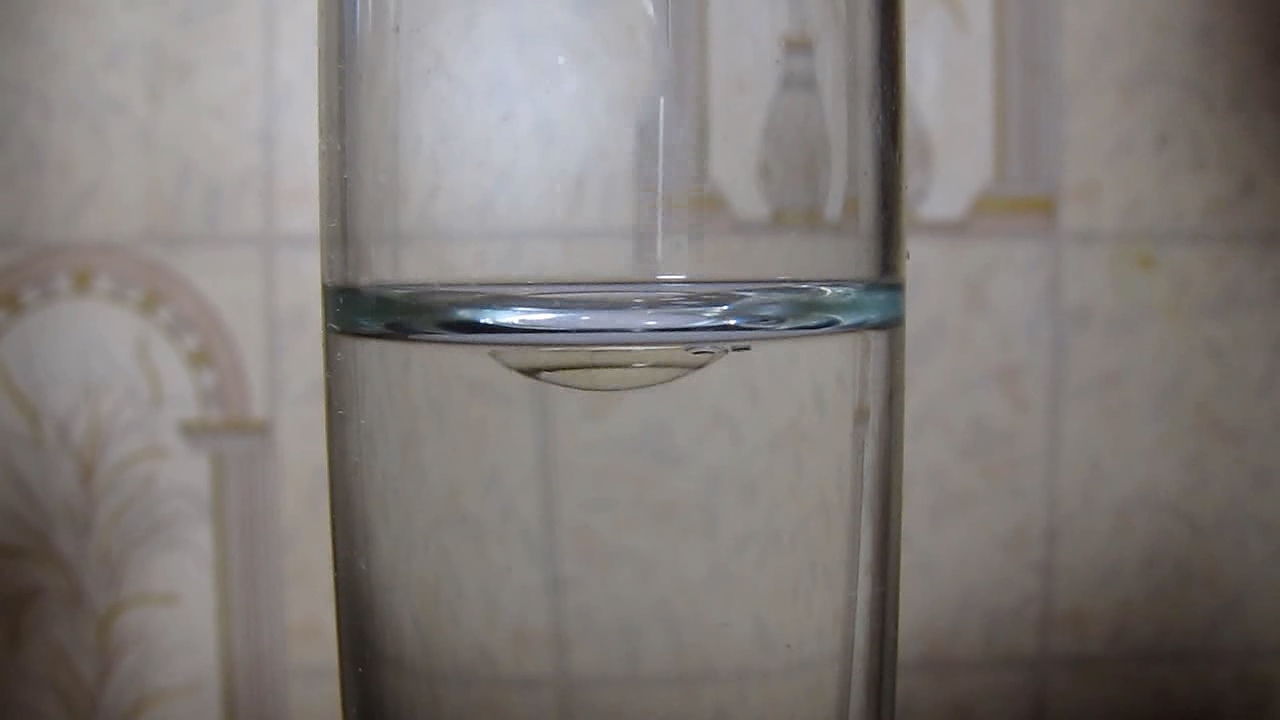

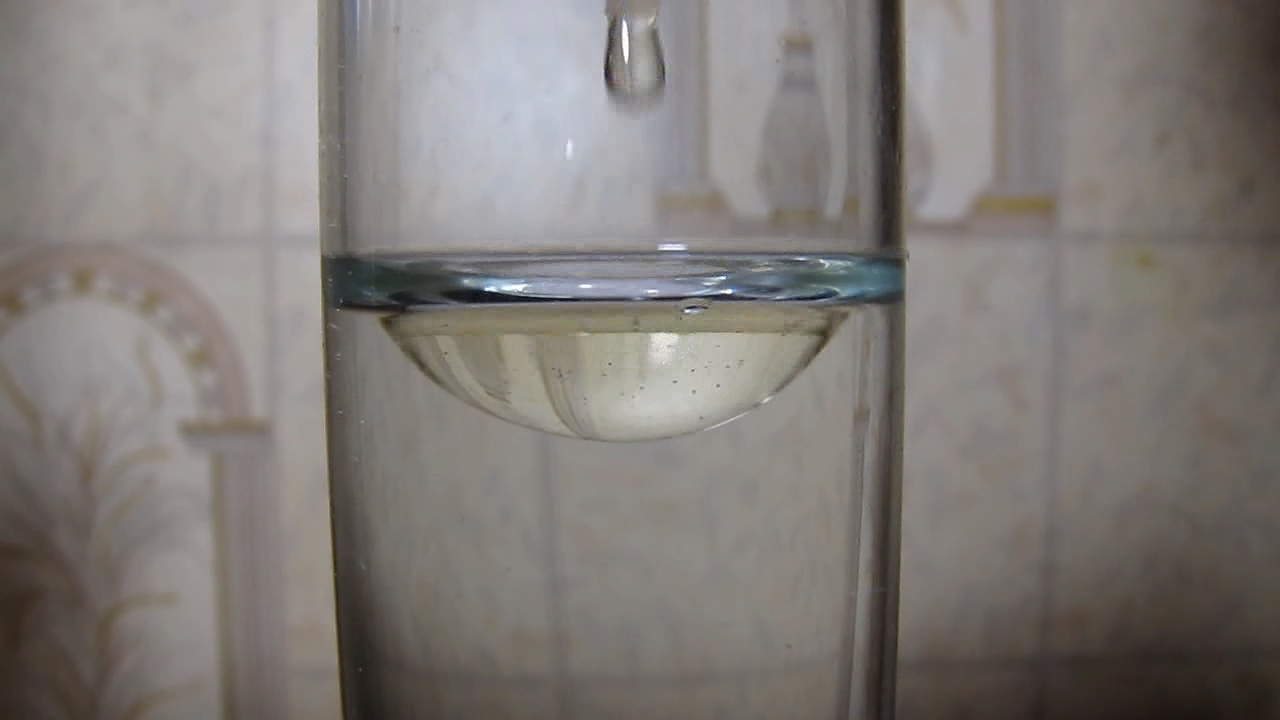

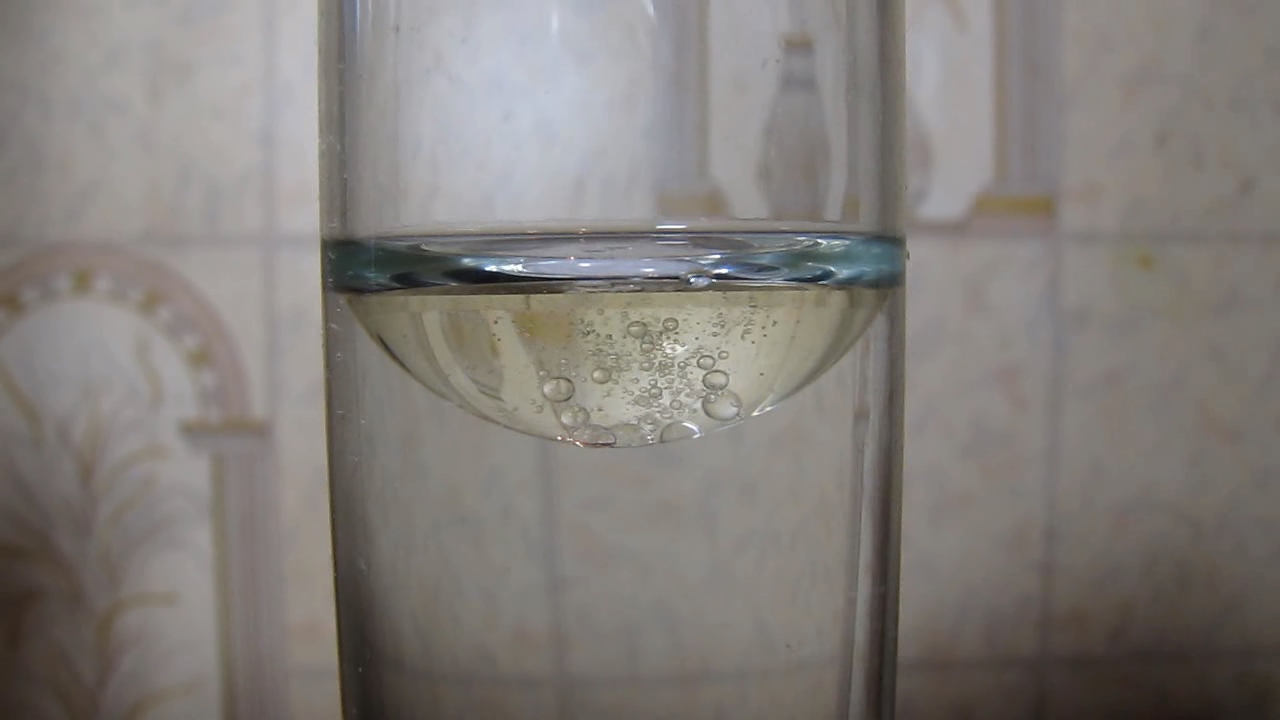

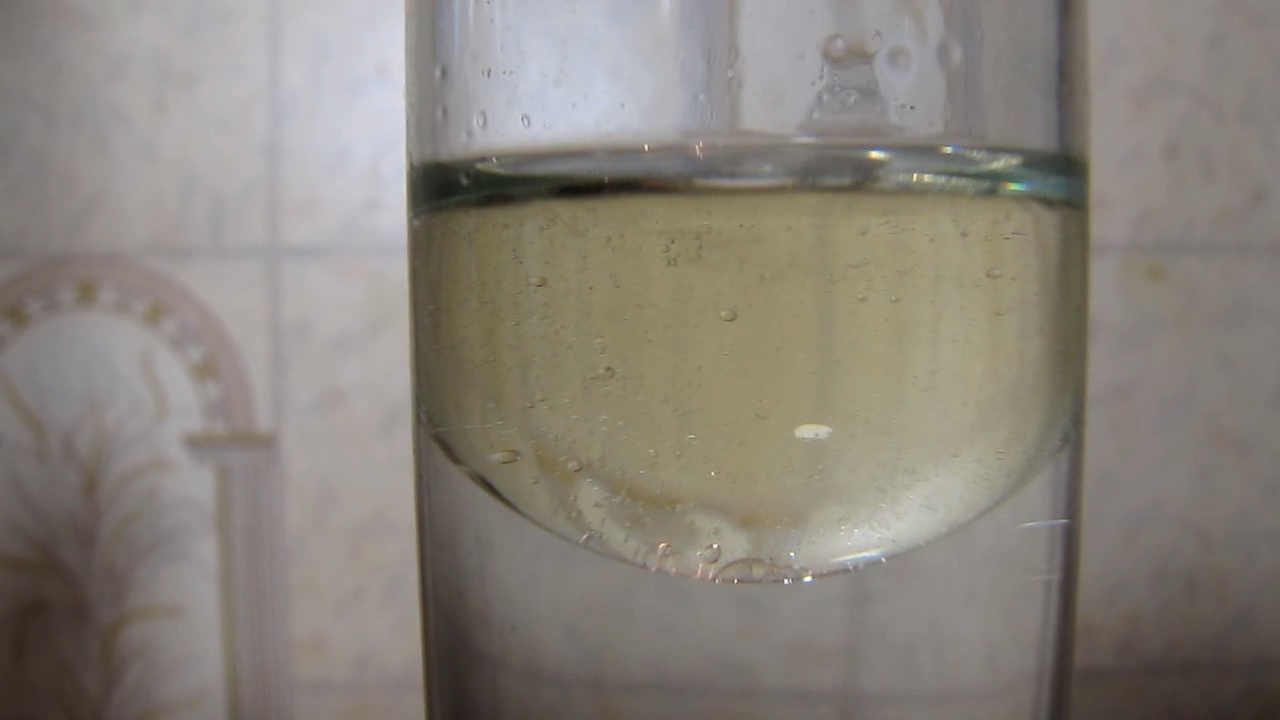

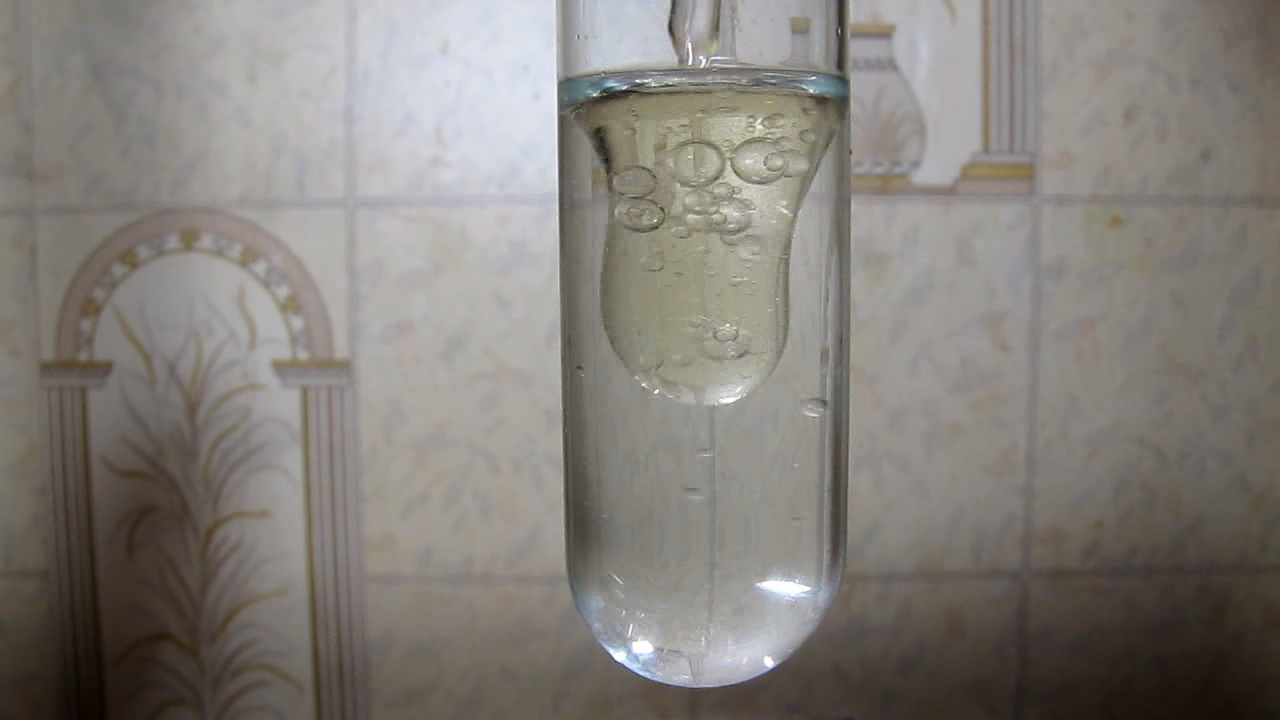

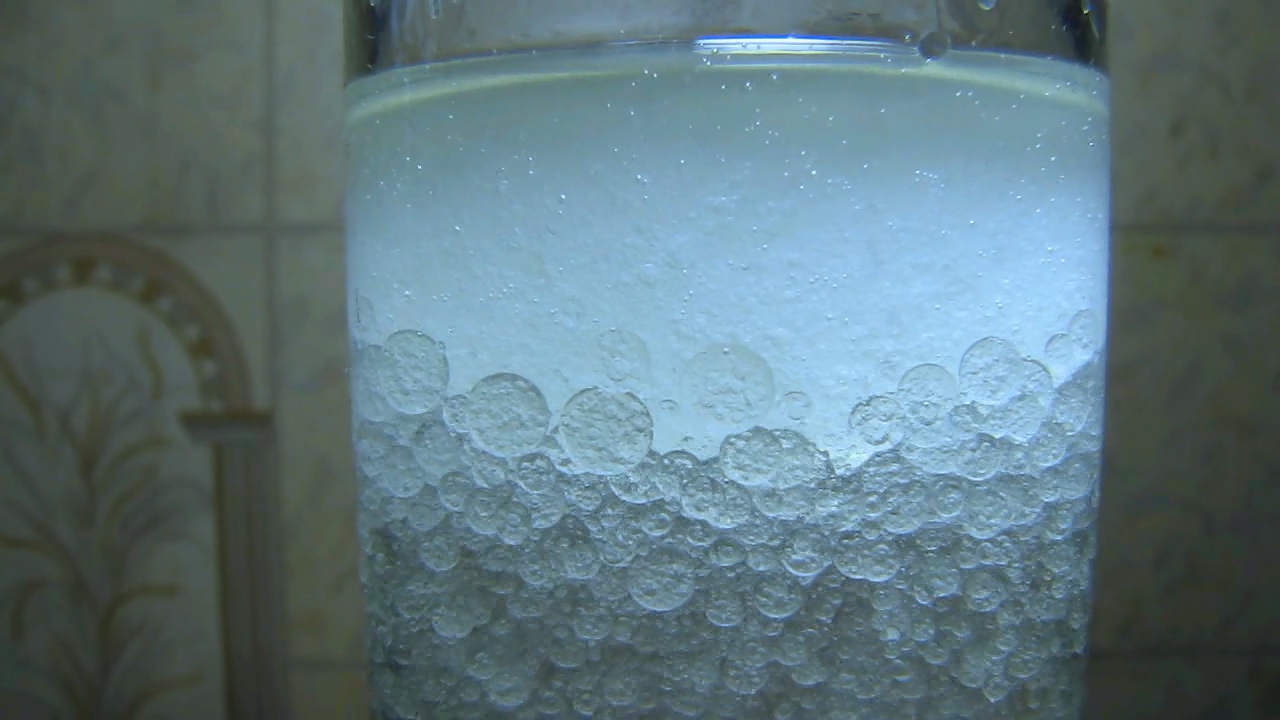

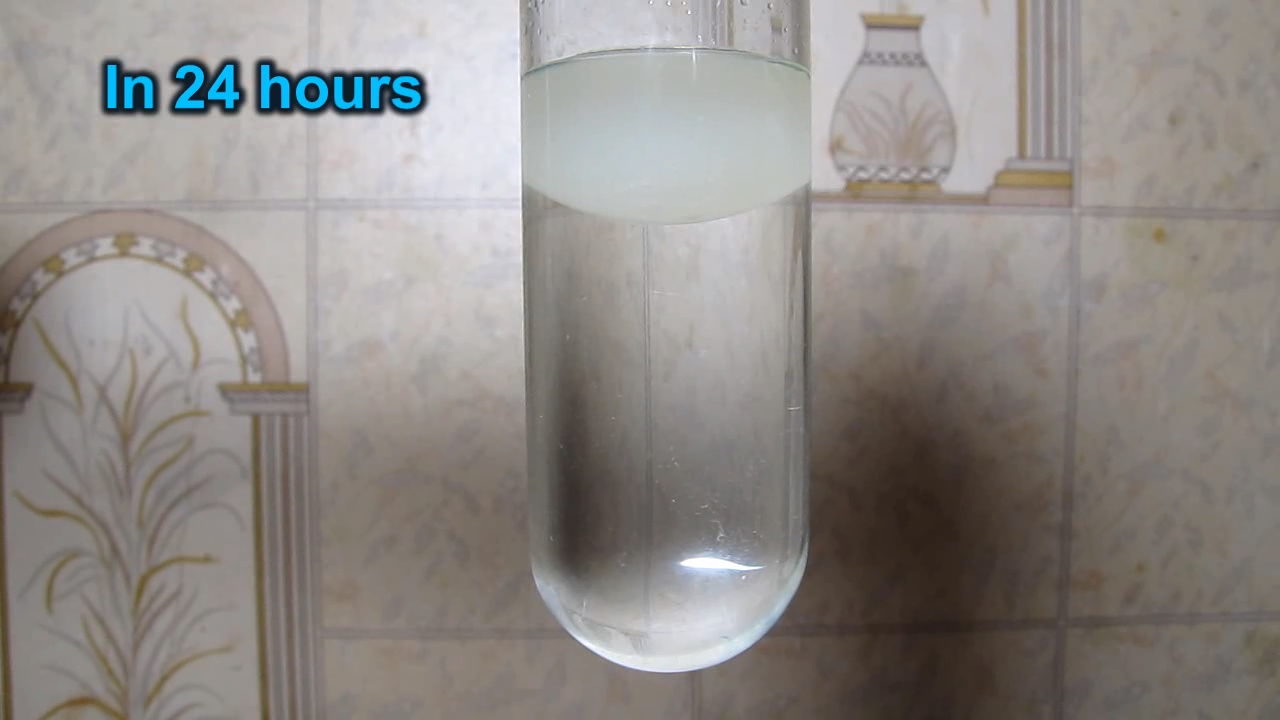

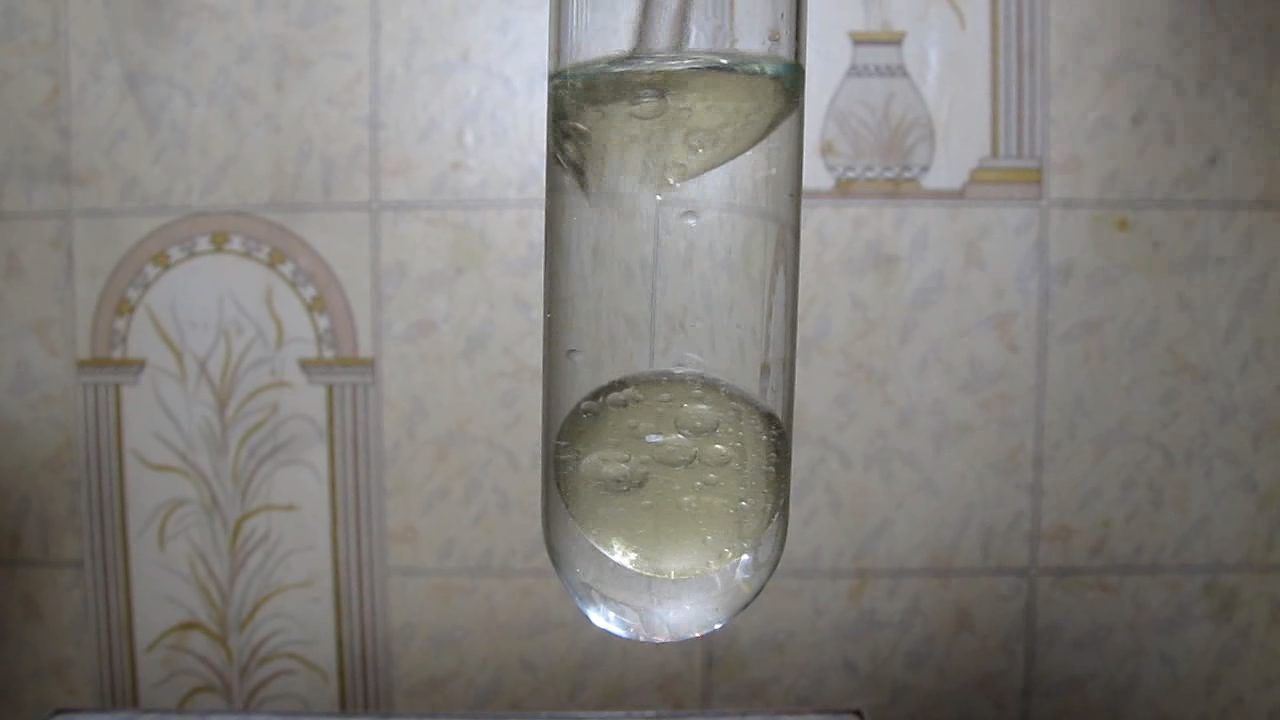

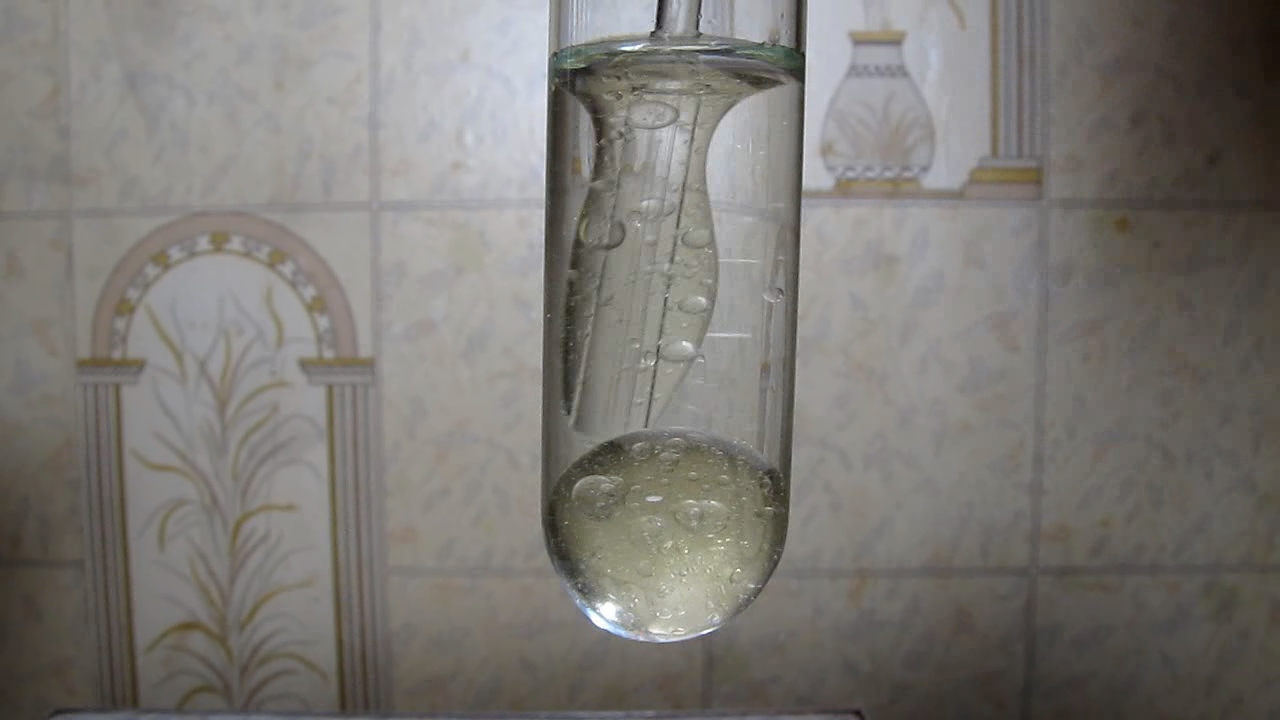

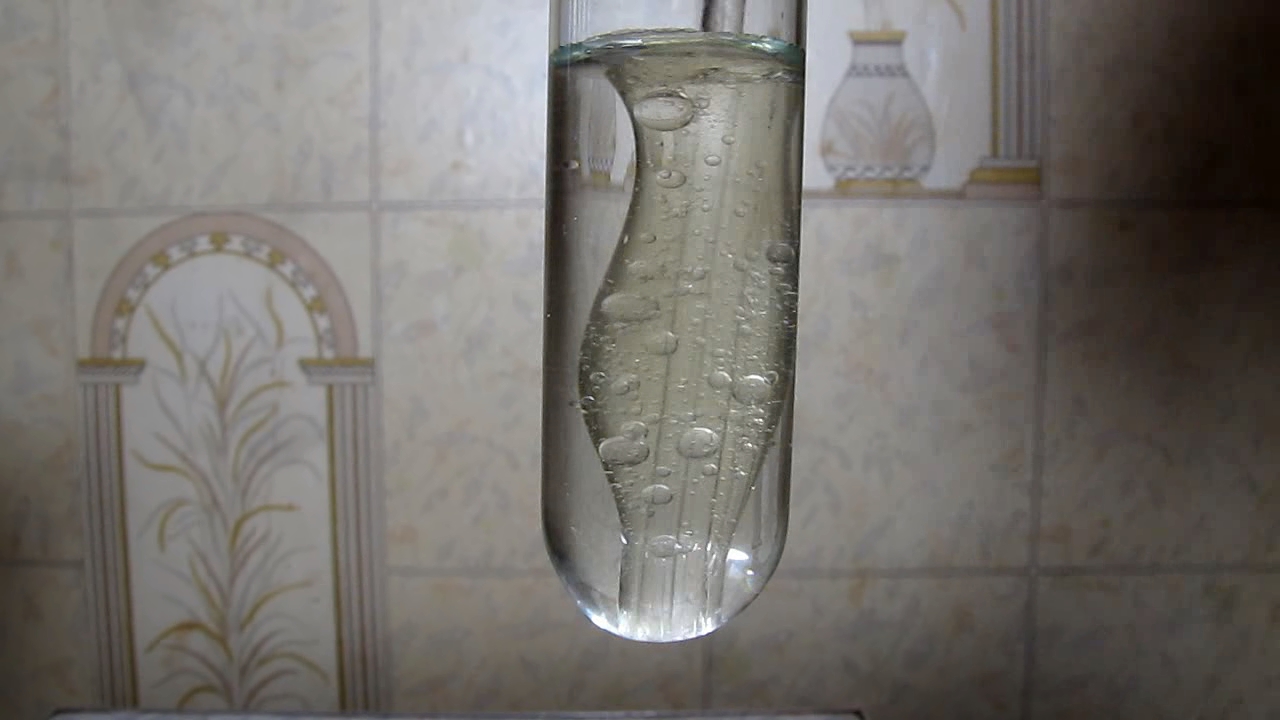

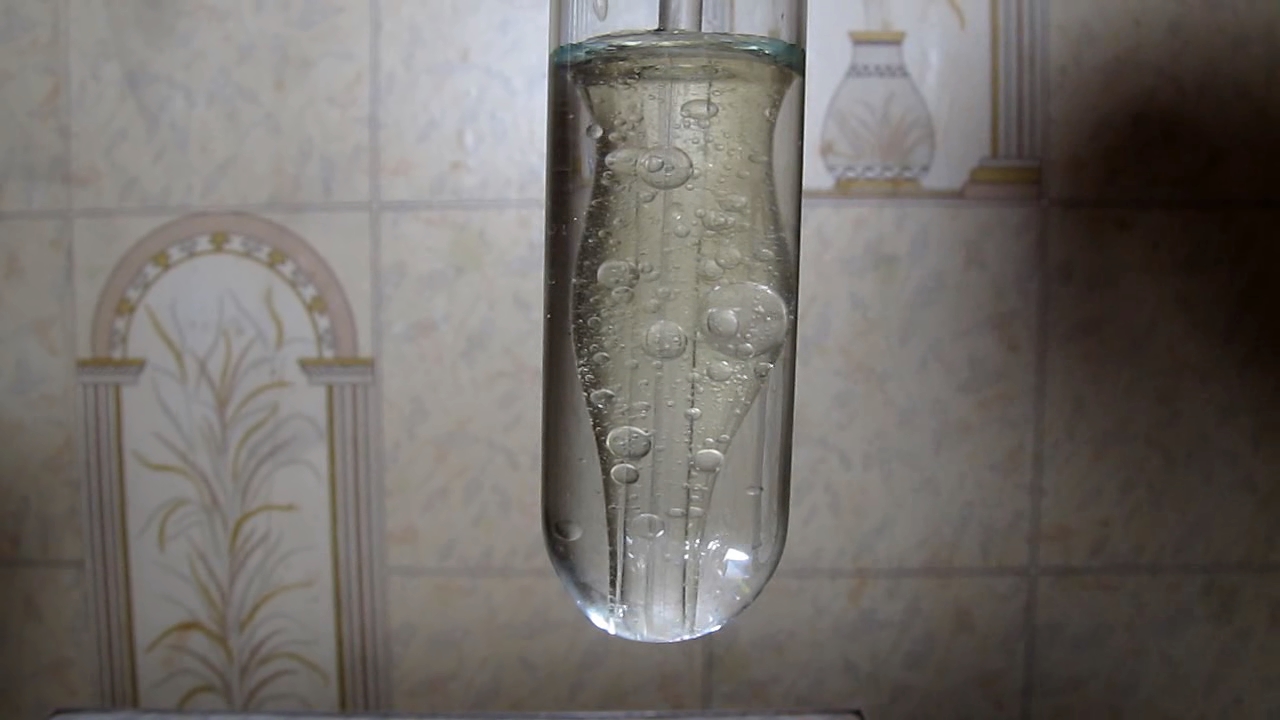

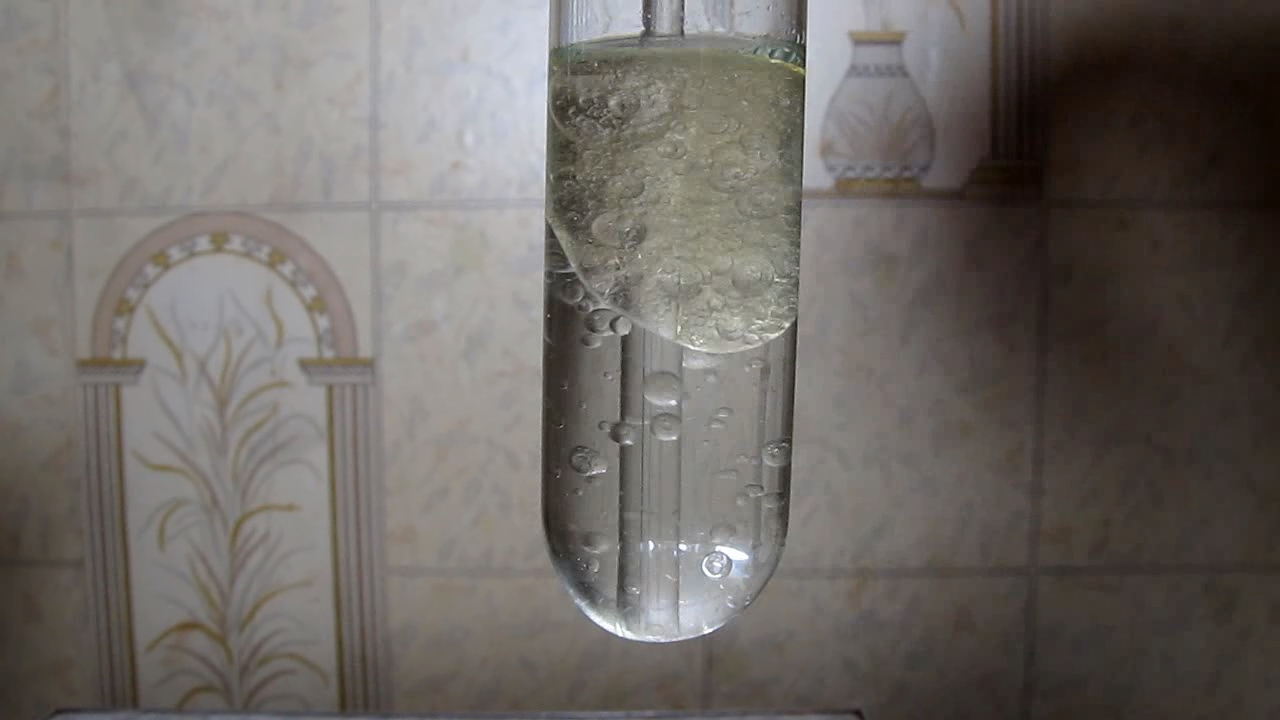

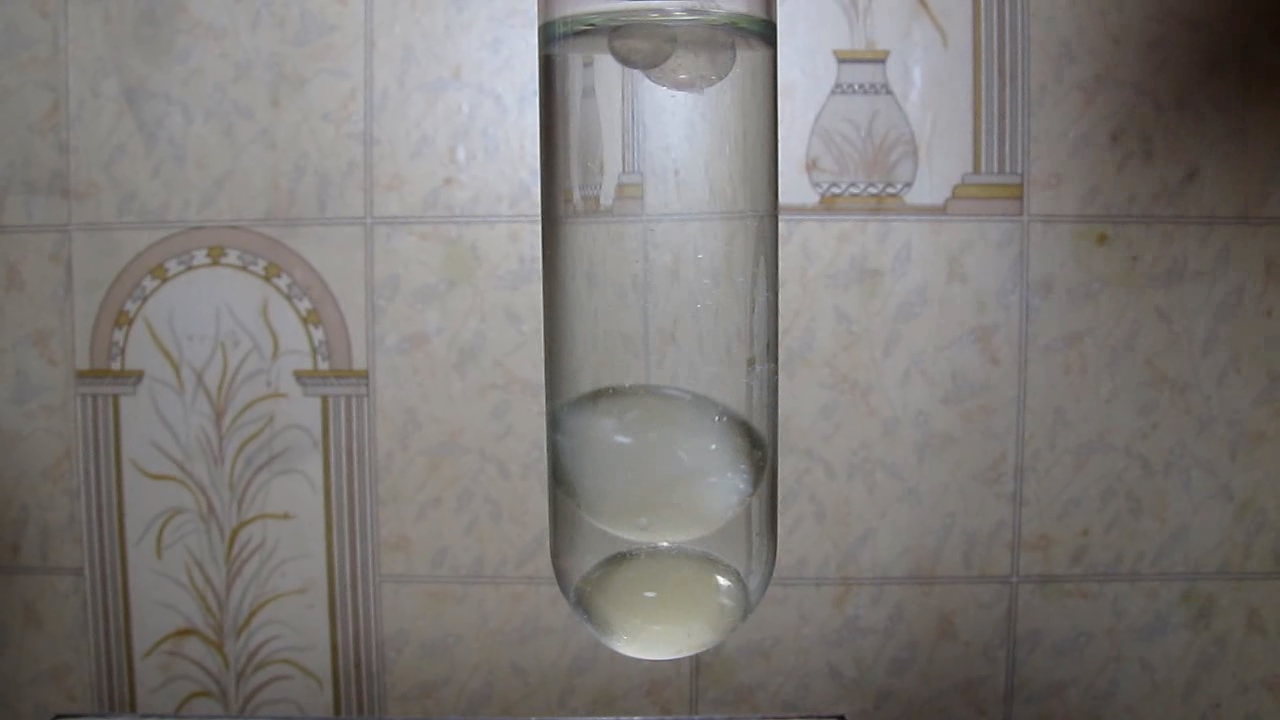

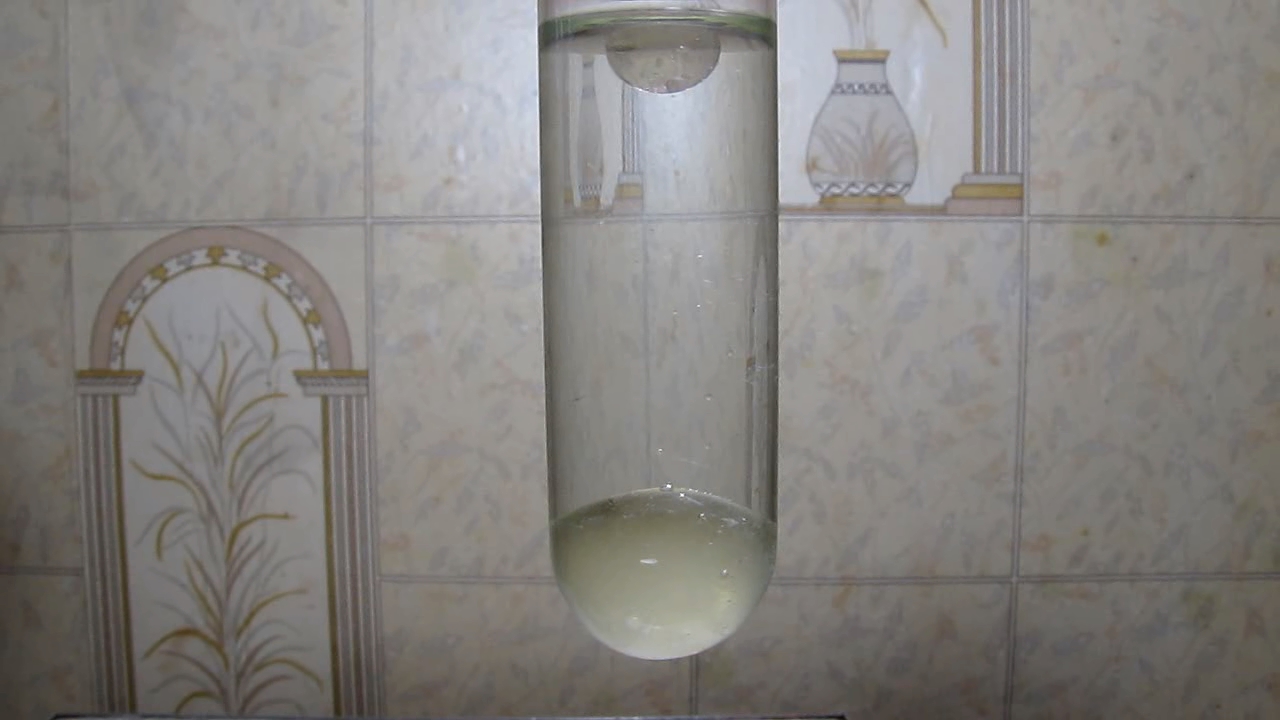

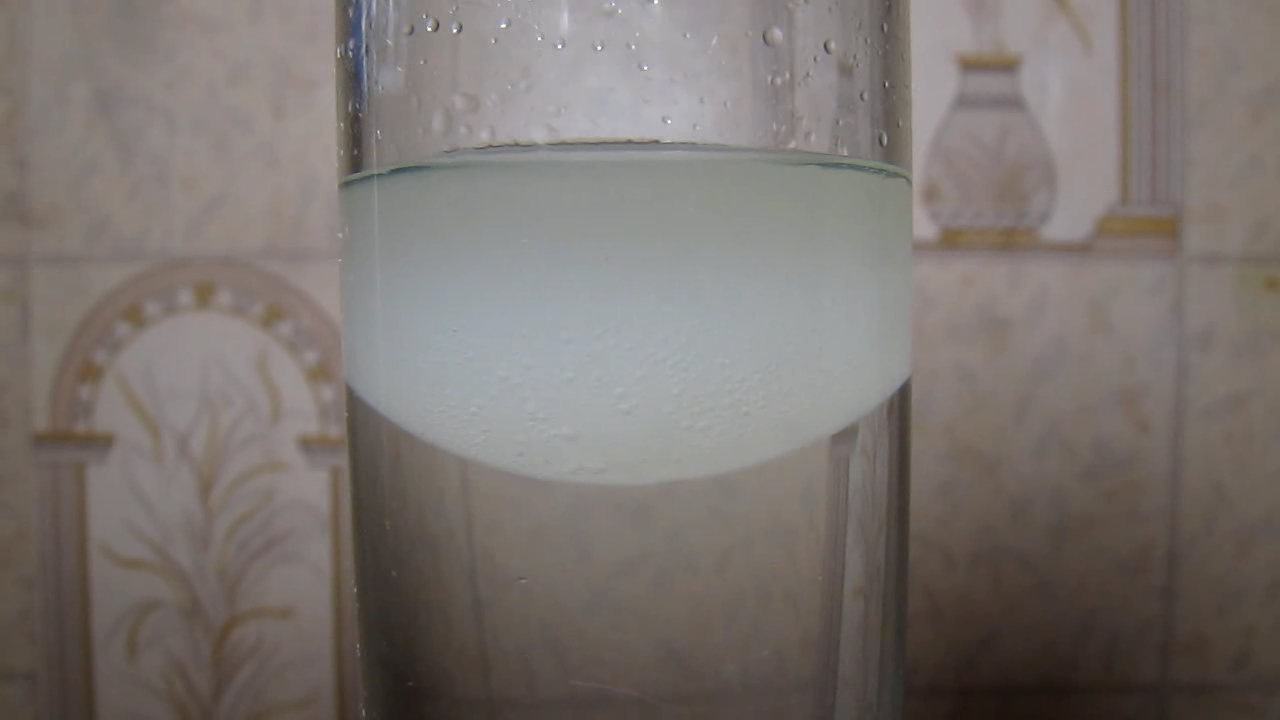

Растительные масла, аммиак и лавовая лампа 'наоборот' Подсолнечное масло и раствор аммиака - часть 1  I found this statement in another source: 'Lava-type lamps can be made with water mixed with isopropyl alcohol as one phase and mineral oil as the other. Other materials, which may be used as oil phase ingredients include benzyl alcohol, cinnamyl alcohol, diethyl phthalate, and ethyl salicylate.' A solution of isopropyl alcohol in water is the top liquid, and mineral oil is the bottom one. This looks more like the truth. By adding isopropyl alcohol to water, you can reduce its density and make the density of the isopropyl alcohol solution slightly lower than the density of mineral oil. Now, the logical thing was to find data on the densities of readily available liquids that could be used in a lava lamp. At that moment, an idea suddenly came to my mind, which forced me to delay the experiments with the lava lamp. Imagine vegetable oil sinking in water! I saw this picture vividly in my imagination... The water was ordinary, and no ethanol or isopropanol was added. How is this possible? After all, the density of vegetable oils is typically less than the density of water (about 1 g/cm3). The density of many mineral oils (technical mixtures of hydrocarbons obtained from crude oil) is also less than 1 g/cm3. How is this possible? I told you the truth and only the truth... but not the whole truth. A concentrated ammonia solution is 75% water, 25% ammonia and no added alcohols. From memory, the density of a concentrated aqueous ammonia solution (25% wt) is 0.89 g/cm3, and the density of vegetable oils is more than 0.9 but less than 1.0 g/cm3. As a result, the oils float in water but should sink in a concentrated ammonia solution. I googled. Below are the densities of some liquids of interest to us. Glycerol - 1.261 g/cm3 Ammonia solution - 0.880 g/cm3 Sunflower oil - 0.9188 g/cm3 Isopropyl alcohol - 0.786 g/cm3 If you believe this data, sunflower oil should sink in an aqueous ammonia solution. However, the density of glycerol is not suitable for our purposes: it is significantly heavier than the other liquids listed. Of course, when doing important experiments or designing chemical plants, you should rely only on data from reputable, trustworthy sources. And even they should be double-checked in other authoritative sources. However, data found using Google or other search engines may be a good starting point for trial experiments. This significantly speeds up the work. Then, before moving forward, it is necessary to ensure the information is accurate. Let us start the experiment. I poured a concentrated aqueous solution of ammonia (the concentration is about 25%) into a test tube, then began to add sunflower oil drop by drop, then in a thin stream. The first drop of oil, falling into the ammonia, did not sink but remained floating on top. The following portions of oil also did not sink but remained on top, forming a yellow layer. The interface between the liquids was not flat but resembled a lens. In other words, the surface of the oil was convex, like a magnifying lens (conversely, the surface of the solution was concave under the oil layer, like the meniscus of water in a burette or like a concave lens). The more sunflower oil I added, the more the liquid interface sagged. Now, only the force of surface tension prevented the oil from sinking. If I add more oil, its weight should overcome the resistance of this force. However, the oil did not sink but remained on top. I tried to press with a glass rod, "pushing" the sunflower oil down, but it did not help. The oil sank along with the glass rod and then floated up. There was no doubt: although the densities of the two liquids were close, the density of the oil turned out to be slightly less than the density of my ammonia solution. Therefore, sunflower oil did not sink in the ammonia. To make sure, I mixed the contents of the test tube with a glass rod. Sunflower oil turned into large drops and distributed over the ammonia layer. With more intense mixing, the drop size decreased. However, after the mixing was stopped, the droplets floated upward, combining into a layer of oil. As a result, the ammonia layer relatively quickly became transparent again (without turbidity). At the same time, the layer of sunflower oil was white and cloudy, which resembled the formation of a 'water-in-oil' emulsion, but let us not rush to conclusions regarding the emulsion. What is the reason for the failure of the experiment? To be honest, BEFORE the experiment, I hoped that the sunflower oil would sink in the ammonia solution (and wanted this); however, I understood that the oil could remain on top. There are several possible reasons for failure. The density value of an ammonia solution found on the Internet is unreliable; could this be the case? Of course, it can. However, I came across similar values for the density of ammonia solutions in several reference books on analytical chemistry back in the days when there was no public Internet and public computers. Another reason. If the seller or manufacturer claims that the ammonia concentration in the solution is 25% (by weight), then this is not necessarily true. Sellers nowadays often deliberately deceive buyers. The concentration of ammonia in the solution may be lower than stated. The lower the concentration of the ammonia aqueous solution, the higher its density. As a result, the density of the ammonia solution turned out to be higher than the density of sunflower oil. Even if the initial ammonia concentration was 25%, this compound could partially evaporate from the solution during transportation, packaging and storage. Moreover, I have already opened and used this bottle. As a result, the ammonia concentration could decrease. Even when stored in a tightly closed plastic bottle, ammonia (and water) can escape through the walls and cap. Another possible reason is that sunflower oil is not an individual chemical substance but a complex mixture of compounds, the composition of which can vary. Accordingly, the density of different batches of sunflower oil may also differ. Unlike the previous case, the difference in oil density does not necessarily indicate variations in product quality.   It also turned out that the density value of '0.89 g/cm3' corresponds to an ammonia concentration of not 25, but 30%. Where did the value '0.880 g/cm3' come from then? It turns out that this is the density of a saturated aqueous ammonia solution. Commercially available ammonia solution usually has a lower concentration since handling a saturated solution of ammonia involves additional inconveniences and risks. In our country, they commonly sell '25% concentrated ammonia solution,' which indicates it is not saturated. For example, Wikipedia writes: 'The maximum concentration of ammonia in water (a saturated solution) has a density of 0.880 g/cm3 and is often known as '.880 ammonia'. <...> At 15.6°C (60.1°F), the density of a saturated solution is 0.88 g/ml, and it contains 35.6% ammonia by mass.' I have never seen such a name in our country. Thus, it was impossible to 'drown' sunflower oil in the aqueous ammonia solution. On the one hand, a negative result is also a result. I can mount a video demonstrating that sunflower oil does not sink in a concentrated ammonia solution. However, it turned out that even such a result still needs to be fought for. At the beginning of the experiment described, I added sunflower oil to the ammonia solution. As a result, I noticed that a white particle got into the test tube along with the oil. When shooting a macro video, foreign particles spoil the video, so I tried to fix the problem. As a result, I felt like a stupid donkey or rather like a cat... I did not realize it immediately, but the next day, I understood WHAT I had been doing. Many people probably know that cats love to chase a sunbeam or a laser pointer. Not all cats, but most. For example, one of my cats was so smart that she took trying to play with her using a laser as an insult. But the rest of the animals loved and demanded such games. Cats perceive the laser dot as a material object suitable as prey.  That is right. I tried to catch an analogue of a 'laser dot' with a pipette, being confident this was a material object. Perhaps I behaved like crazy, but everything seemed logical during the experiment. The shape of the liquid surface was very unusual, causing the reflection to resemble a white solid particle, almost like a large piece of dandruff. This 'particle' appeared to be designed to enter the test tube with my fluids and ruin the video of the experiment. It was only the next day that I realized it was merely a reflection of the lamp, not a solid impurity. This realization dawned on me as I carefully reviewed the footage. Despite the numerous 'lyrical digressions' in the article, it is devoted to chemistry and physics, not to artistic images. I set a specific task, and it had to be achieved. It is necessary to ensure that the sunflower oil sinks to the bottom in an ammonia solution. First, I repeated the experiment described above, no longer trying to 'hunt' for the reflection of the lamp using a pipette. I knew that sunflower oil would not drown in ammonia, but it was necessary to shoot an additional video. This time, the sunflower oil also formed a top layer with a convex surface (like a magnifying glass or a ball that lies on the table). Attempts to 'drown' the layer of the oil with a glass rod led to the fact that the oil sank but then floated up again [1]. During mixing, the sunflower oil broke up into droplets; as a result, the liquid in the test tube became cloudy. After the stirring stopped, the droplets floated to the surface and merged into a layer of oil on top. As a result, the ammonia solution became transparent again, but the oil remained white and cloudy when standing (even after two days). Moreover, when standing, the white colour of the oil intensified. This behaviour is not at all typical for an emulsion. In the next part, I will try to explain this phenomenon. Looking ahead, I will say that I achieved that sunflower oil sank in an aqueous solution of ammonia (using the same ammonia solution and the same oil). __________________________________________________ 1 I noticed spherical objects that formed in the oil layer with gentle stirring. At first, I thought I was observing 'soap antibubbles'. Ordinary soap bubbles have been familiar to us since childhood. It is gas enclosed in a thin film of liquid. In turn, soap antibubble is a droplet of liquid surrounded by a thin film of gas. Previously, I observed the formation of soap antibubbles when a soap solution was dripped into a vessel with a soap solution. It is possible that such antibubbles can occur in sunflower oil even without the addition of surfactants. However, it turned out that these balls did not float up in the oil but slowly sank, then combined with the lower layer of the ammonia solution. Consequently, these objects were ordinary drops of an ammonia solution (not enclosed in a shell of air). Обратил внимание на объекты сферической формы, которые образовались в слое масла при осторожном перемешивании. Сначала я решил, что наблюдаю 'мыльные антипузыри'. Обычные мыльные пузыри знакомы нам с детства. Они представляют собой газ, заключенный в тонкую оболочку жидкости. В свою очередь мыльные антипузыри представляют собой жидкость, окруженную тонкой оболочкой газа. Раньше я наблюдал образование мыльных антипузырей, когда капал раствор мыла в сосуд с раствором мыла. Возможно, такие антипузыри могут возникать в подсолнечном масла даже без добавки поверхностно-активных веществ. Однако оказалось, что эти шарики не всплывали в масле, а медленно опускались вниз, затем объединяясь с нижним слоем раствора аммиака. Следовательно, данные объекты представляли собой обычные капли раствора аммиака (не заключенные в оболочку из воздуха). |

|

Растительные масла, аммиак и лавовая лампа 'наоборот'

Во время экспериментов с целью получения эмульсий из растительного масла я вспомнил про 'лавовую лампу'. Она представляет собой декоративный светильник, изобретенный в 1960-х годах. Светильник имеет прозрачный корпус, заполненный двумя несмешивающимися жидкостями. Данные жидкости имеют близкую, но не равную плотность. Верхняя жидкость прозрачна и бесцветна или слабо окрашена. Под ней расположена другая чуть более тяжелая жидкость, которая ярко окрашена. При включении светильника нижний слой нагревается расположенной под ним лампой накаливания, поэтому плотность нижней жидкости уменьшается. В результате нижняя жидкость становится легче верхней и всплывает в виде ярких крупных капель, которые образуют причудливые фигуры при свете лампы. Вверху резервуара эти капли остывают, их плотность становится выше плотности окружающей ('верхней') жидкости, после чего капли опускаются на дно, где опять нагреваются. Происходит обыкновенная конвекция, которая становится причиной возникновения 'арт-объекта'.

Подсолнечное масло и раствор аммиака - часть 1  В другом источнике нашел утверждение: 'Lava-type lamps can be made with water mixed with isopropyl alcohol as one phase and mineral oil as the other. Other materials, which may be used as oil phase ingredients include benzyl alcohol, cinnamyl alcohol, diethyl phthalate, and ethyl salicylate.' Раствор изопропилового спирта в воде - верхняя жидкость и минеральное масло - нижняя. Это уже больше похоже на правду. Добавляя в воду изопропиловый спирт, можно уменьшить ее плотность и сделать, чтобы плотность раствора изопропилового спирта была чуть ниже плотности минерального масла. Теперь логичным было найти данные о плотности общедоступных жидкостей, которые потенциально можно использовать для лавовой лампы. В этот момент в голову неожиданно пришла идея, которая заставила меня отложить эксперименты с лавовой лампой. Представьте себе, что растительное масло тонет в воде! Я ярко видел эту картину в своем воображении... Вода была самая настоящая, без добавок этанола или изопропанола. Как такое возможно? Ведь плотность растительных масел обычно меньше плотности воды (около 1 г/см3). Плотность многих минеральных масел (технических смесей углеводородов, полученных из нефти) тоже меньше 1 г/см3. Как такое возможно? Я сказал вам правду и только правду... но не всю правду. Концентрированный раствор аммиака - это на 75% вода и только на 25% аммиак, зато - никаких добавок спиртов. По памяти, плотность концентрированного водного раствора аммиака (25% вес.) равна 0.89 г/см3, а плотность растительных масел больше 0.9, но меньше 1.0 г/см3. В результате масла всплывают в воде, но должны тонуть в концентрированном растворе аммиака. Погуглил. Ниже приведены плотности некоторых интересующих нас жидкостей. Glycerol - 1.261 g/cm3 Ammonia solution - 0.880 g/cm3 Sunflower oil - 0.9188 g/cm3 Isopropyl alcohol - 0.786 g/cm3 Если верить этим данным, подсолнечное масло должно тонуть в водном растворе аммиака. Зато плотность глицерина для наших целей подходит плохо: он существенно тяжелее других приведенных жидкостей. Конечно, для важных экспериментов или при проектировании химических производств следует использовать исключительно данные из солидных, заслуживающих доверия источников. И даже их следует перепроверить в других авторитетных источниках. Однако для пробных экспериментов в качестве отправной точки могут подойти данные, найденные с помощью Google или других поисковых систем. Это существенно ускоряет работу. Потом, прежде чем двигаться дальше, важно убедиться в достоверности и точности этой информации. Приступим к эксперименту. Налил в пробирку концентрированный водный раствор аммиака (концентрация около 25%), потом стал добавлять подсолнечное масло по каплям, затем - тонкой струйкой. Первая капля, масла, попав в аммиак, не утонула, а осталась плавать сверху. Следующие порции масла также не утонули, а остались сверху, образуя желтый слой. Граница раздела жидкостей не была плоской, а напоминала линзу. Другими словами, поверхность масла была выпуклой, словно увеличительная линза (и наоборот, поверхность раствора под слоем масла была вогнутой, как мениск воды в бюретке или как уменьшительная линза). Чем больше я добавлял подсолнечного масла, тем сильнее прогибалась поверхность раздела жидкостей. Казалось, масло вот-вот опустится на дно. Сейчас только сила поверхностного натяжения не позволяла ему утонуть. Если добавить больше масла, его вес должен преодолеть сопротивление этой силы. Но масло не утонуло, а осталось сверху. Попробовал надавить стеклянной палочкой, "подталкивая" подсолнечное масло вниз, но это не помогло. Масло погружалось вместе с палочкой, а потом всплывало. Сомнений не осталось: хотя плотности двух жидкостей были близки, но плотность масла оказалась немного меньше, чем плотность моего раствора аммиака. Поэтому подсолнечное масло не тонуло в аммиаке. Чтобы убедиться окончательно, я перемешал стеклянной палочкой содержимое пробирки. Подсолнечное масло разделилось на крупные капли, которые распределились по слою аммиака. При более интенсивном перемешивании размер капель уменьшился. Однако после прекращения перемешивания капли всплывали вверх, объединяясь в слой масла. В результате слой аммиака сравнительно быстро снова стал прозрачным (без мути). В то же время слой подсолнечного масла был бело-мутным, что напоминало образование эмульсии 'вода-в-масле', но не будем спешить с выводами относительно эмульсии. В чем причина неудачи эксперимента? Если честно, ДО опыта я надеялся, что подсолнечное масло утонет в растворе аммиака (и хотел этого), однако, я понимал, что масло может остаться сверху. Возможных причин неудачи сразу несколько. Значение плотности раствора аммиака, которое я нашел в интернете, недостоверно, может такое быть? Разумеется, может. Однако, аналогичные значения плотности растворов аммиака я встречал в нескольких справочниках по аналитической химии еще во времена, когда не было общедоступного интернета и общедоступных компьютеров. Еще одна причина. Если продавец или производитель утверждает, что концентрация аммиака в растворе равна 25% (весовых), то это не обязательно правда. Продавцы в наше время часто сознательно обманывают покупателей. Концентрация аммиака в растворе может быть ниже заявленной. А чем ниже концентрация водного раствора аммиака, тем выше его плотность. В результате плотность раствора аммиака оказалась выше плотности подсолнечного масла. Даже, если исходная концентрация аммиака составляла 25%, то при транспортировке, фасовке и хранении данное вещество могло частично испариться из раствора. Тем более, что я эту бутылку уже открывал и использовал. В результате концентрация аммиака могла понизится. Даже при хранении в плотно закрытой пластиковой бутылке аммиак (и вода) могут улетучиваться сквозь стенки и пробку. Другая возможная причина состоит в том, что подсолнечное масло - не индивидуальное химическое вещество, а сложная смесь веществ, состав которой может быть разным. Соответственно, плотность разных партий подсолнечного масла может также отличаться. В отличие от предыдущего случая, разница в плотности масла не обязательно указывает на изменение качества продукта.   Также оказалось, что значение плотности '0.89 г/см3' соответствует концентрации аммиака не 25, а 30%. Откуда тогда взялось значение '0.880 г/см3'? Оказывается, это плотность насыщенного водного раствора аммиака. В продажу обычно поступает раствор аммиака более низкой концентрации, поскольку обращение с насыщенным раствором аммиака связано с дополнительными неудобствами и рисками. В нашей стране обычно продают '25% концентрированный раствор аммиака', который насыщенным не является. Например, в Википедии пишут: 'The maximum concentration of ammonia in water (a saturated solution) has a density of 0.880 g/cm3 and is often known as '.880 ammonia'. <...> At 15.6°C (60.1°F), the density of a saturated solution is 0.88 g/ml, and it contains 35.6% ammonia by mass.' У нас в стране я такого названия не встречал. Таким образом, 'утопить' подсолнечное масло в водном растворе аммиака не получилось. С одной стороны, отрицательный результат - тоже результат. Я могу смонтировать видео, которое демонстрирует, что подсолнечное масло не тонет в концентрированном растворе аммиака. Однако, оказалось, что и за такой результат еще нужно побороться. В начале описанного эксперимента я добавлял подсолнечное масло в раствор аммиака. В результате заметил, что вместе с маслом в пробирку попала какая-то белая частица. При съемке макро-видео посторонние частицы портят ролик, поэтому попытался устранить проблему. В результате я почувствовал себя глупым ослом, точнее - котом... Почувствовал не стразу, а на следующий день, осознав, ЧЕМ я занимался. Многие, наверно, знают, что коты любят бегать за солнечным зайчиком и/или за пятном от лазерной указки. Не все коты, но большинство. Например, одна из моих кошек была насколько умной, что восприняла попытку поиграть с ней лазером как оскорбление. А остальные животные - любили и требовали такие игры. Коты думают, что перед ними материальный объект, который подойдет в качестве добычи.  Все верно. Я ловил пипеткой... аналог 'солнечного зайчика', думая, что он материален. Возможно, я и сошел с ума, но во время эксперимента все казалось логичным. Форма поверхности жидкости была очень необычной, поэтому отражение напоминало белую твердую частицу (вроде крупного кусочка перхоти). Эта частица была буквально создана для того, чтобы попасть в пробирку с моими жидкостями и испортить видео эксперимента. Только на следующий день понял, что это было отражение лампы, а не твердая примесь. Это стало очевидным, когда я внимательно посмотрел отснятое видео. Несмотря на многочисленные 'лирические отступления' в статье, она посвящена химии и физике, а не художественным образам. Я поставил конкретную задачу и ее предстояло выполнить. Необходимо добиться того, чтобы подсолнечное масло опустилось на дно в растворе аммиака. Сначала я повторил описанный выше эксперимент, уже не пытаясь 'охотиться' за отражением лампы с помощью пипетки. Я знал, что подсолнечное масло не утонет в аммиаке, но было необходимо снять дополнительное видео. В этот раз подсолнечное масло также образовало верхний слой с выпуклой поверхностью (словно увеличительное стекло или шар, который лежит на столе). Попытки 'утопить' слой масла стеклянной палочкой привели к тому, что масло опускалось, но потом опять всплывало [1]. Во время перемешивания подсолнечное масло распадалось на капли, в результате жидкость в пробирке становилась мутной. После прекращения перемешивания капли всплывали и объединялись в слой масла сверху. В результате раствор аммиака снова становился прозрачным, но масло при стоянии оставалось белым и мутным (даже через двое суток). Более того, при стоянии белый цвет масла усиливался. Такое поведение совсем не характерно для эмульсии. В следующей части я попытаюсь объяснить данное явление. Забегая наперед скажу, что мне удалось достичь того, что подсолнечное масло тонуло в водном растворе аммиака (используя тот же раствор аммиака и то же масло). |

Sunflower oil and ammonia solution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Having noticed a mistake in the text, allocate it and press Ctrl-Enter

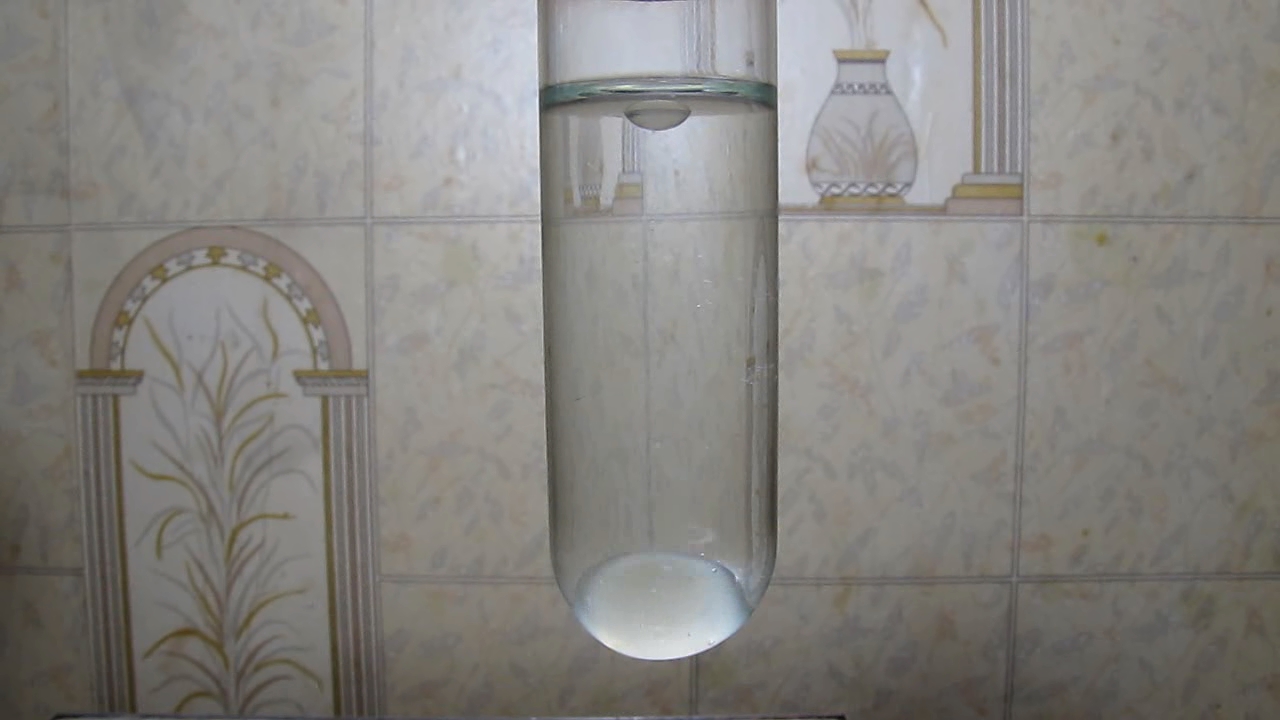

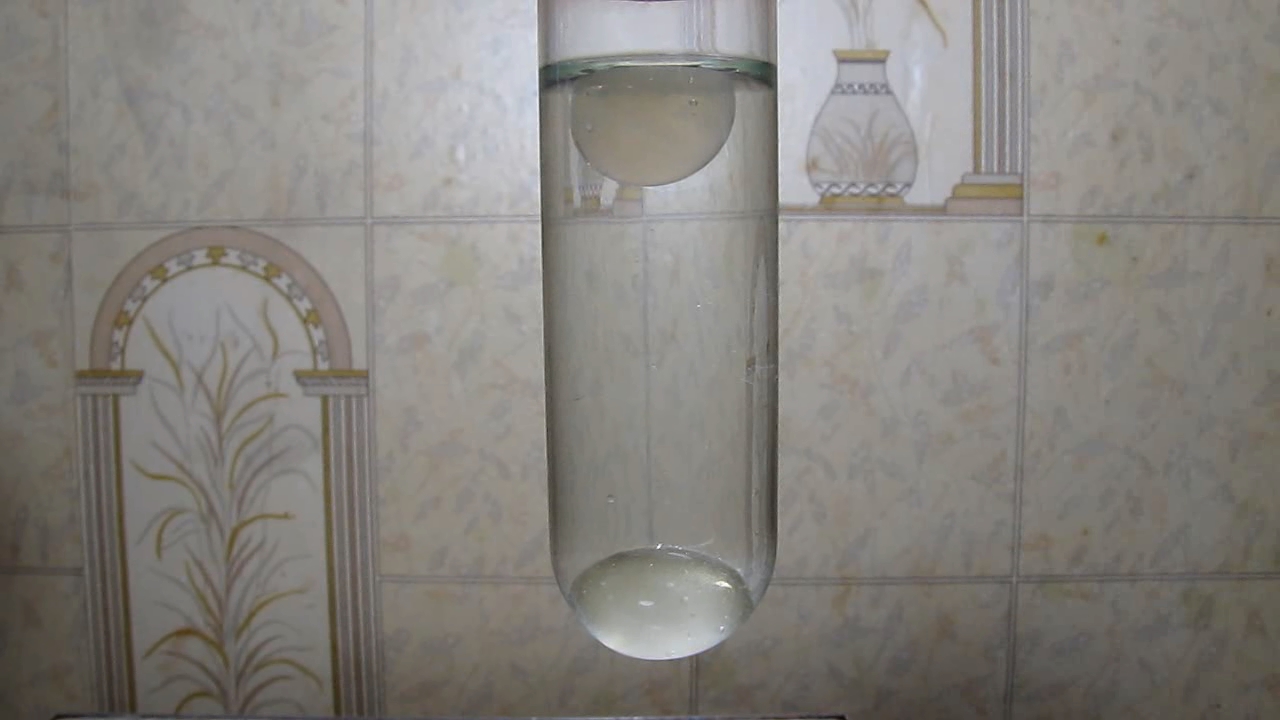

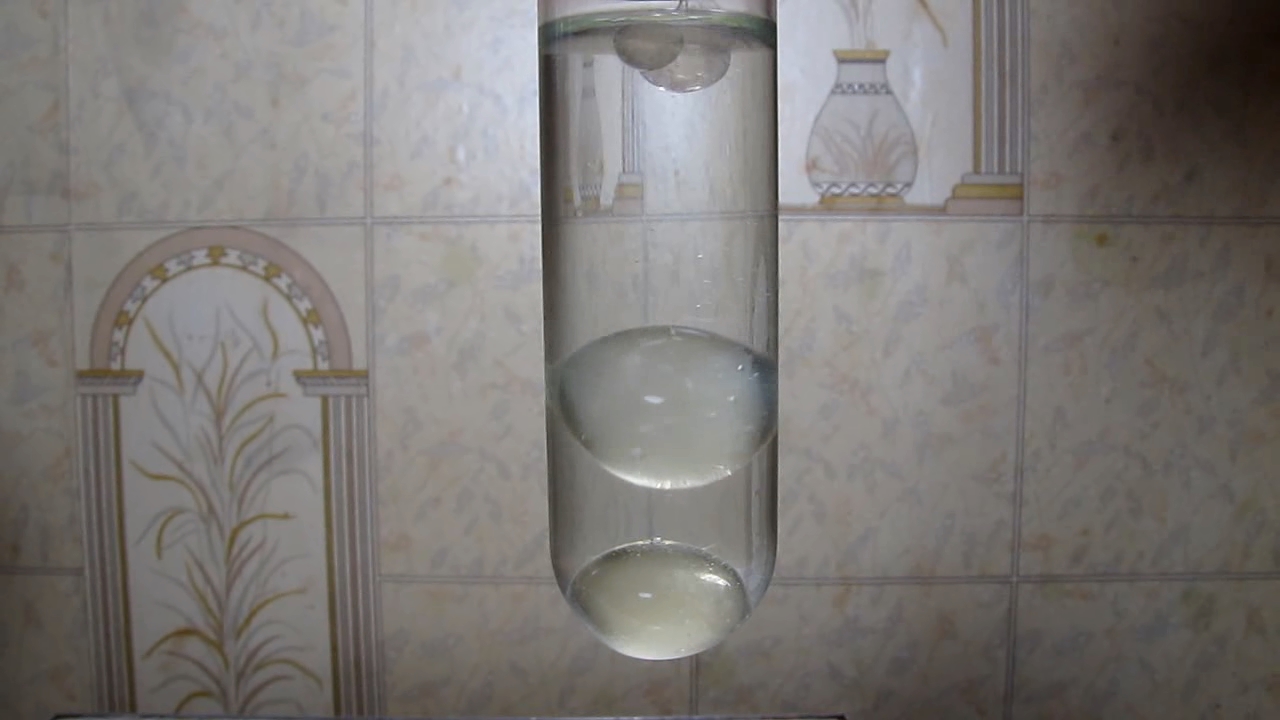

During a previous experiment, unfortunately, sunflower oil did not sink in a concentrated ammonia aqueous solution (~25% wt.). Thus, this experiment was not successful. To achieve a positive result, it is necessary to either slightly increase the density of the sunflower oil or slightly decrease the density of the ammonia solution, which were used in the experiment.

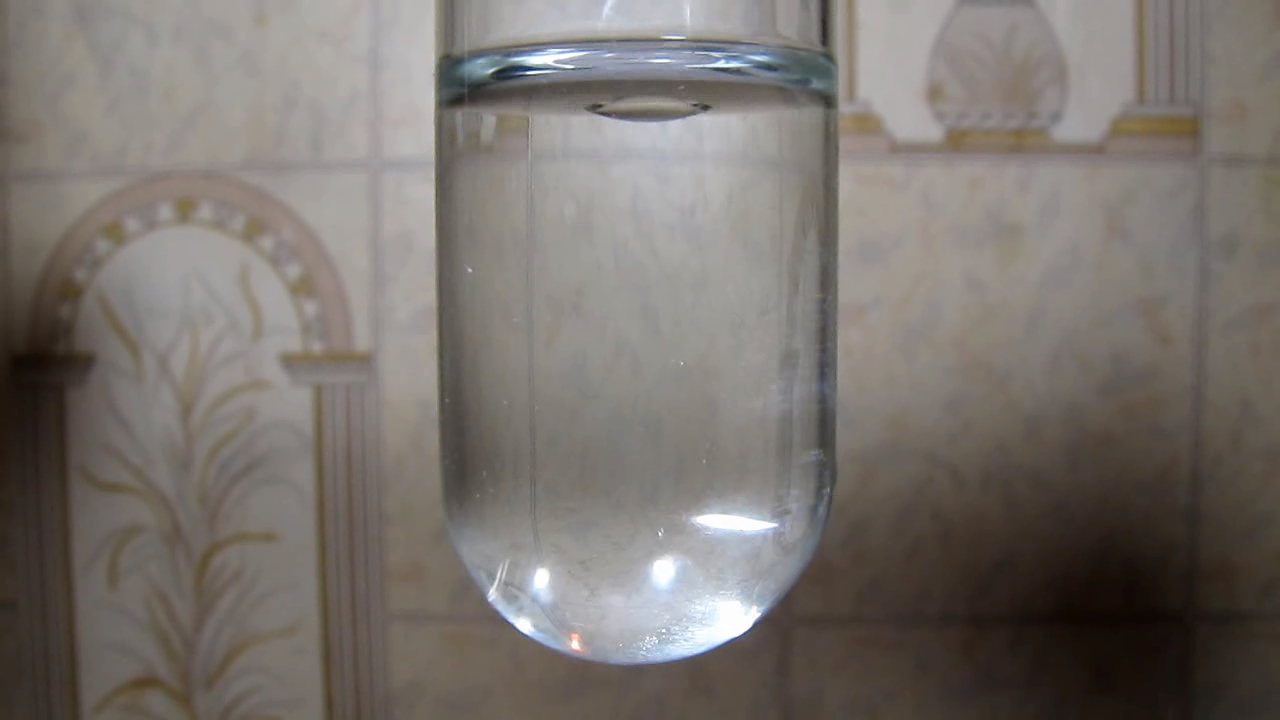

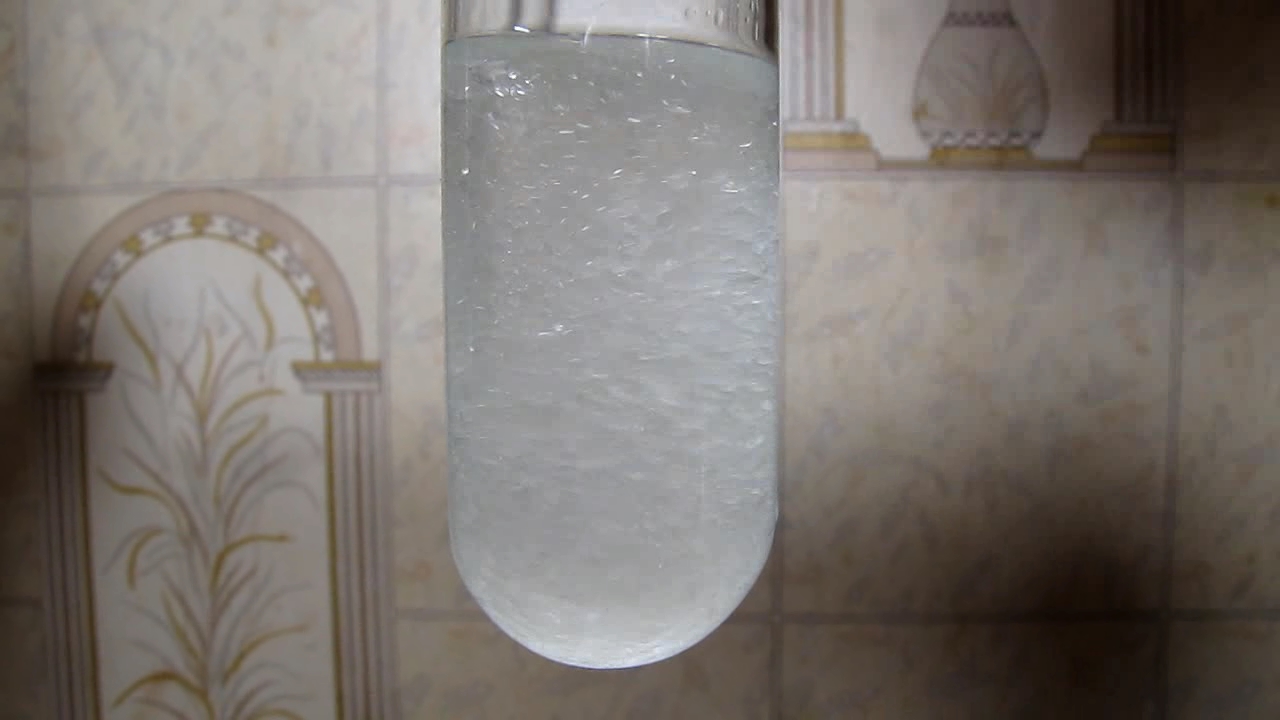

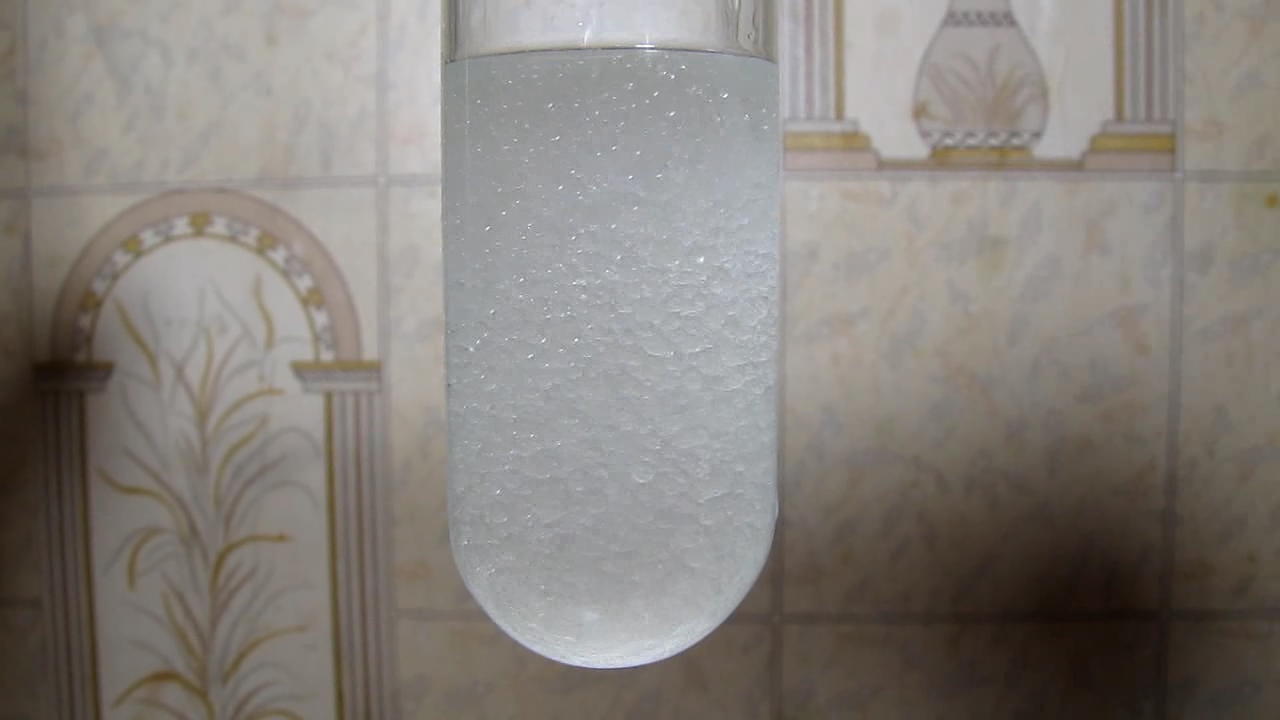

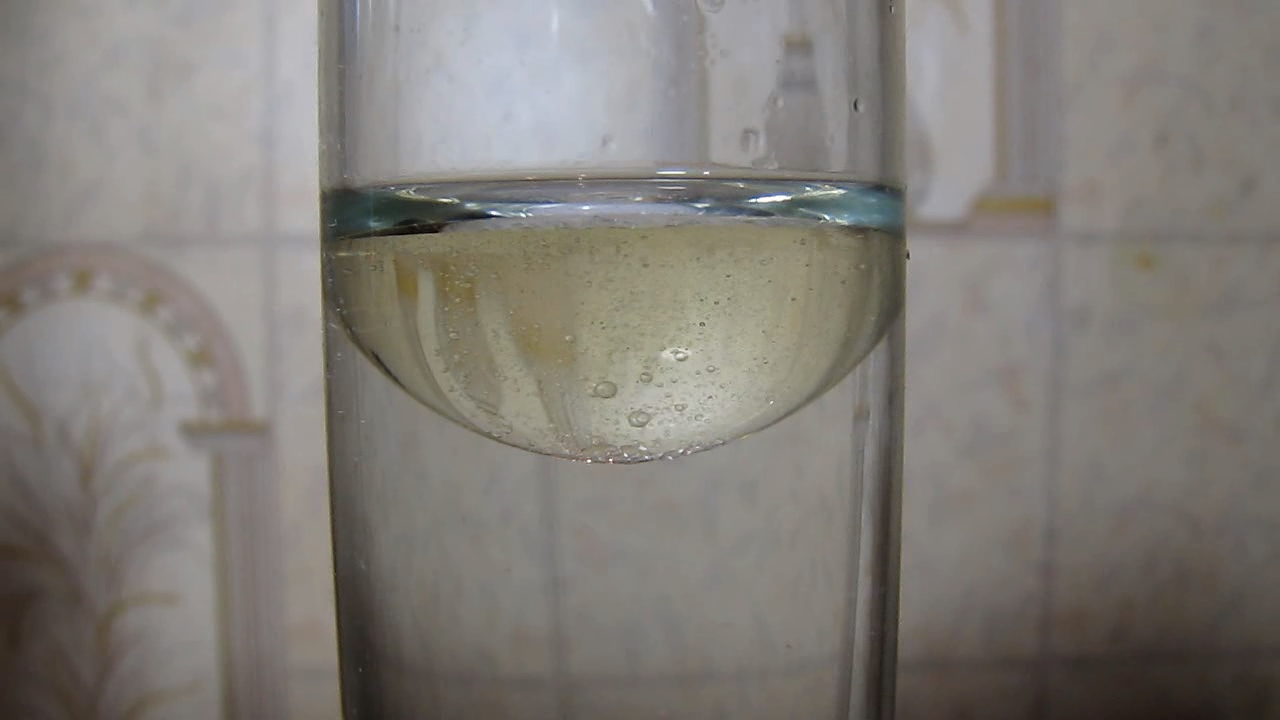

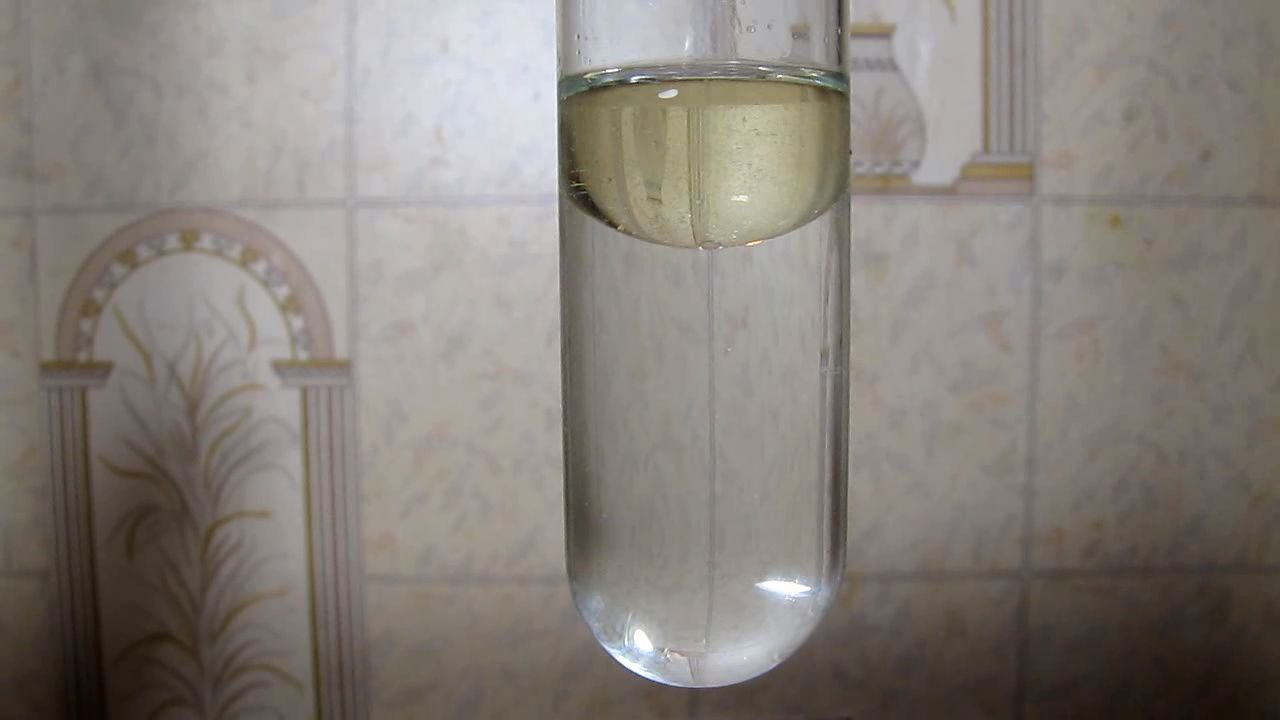

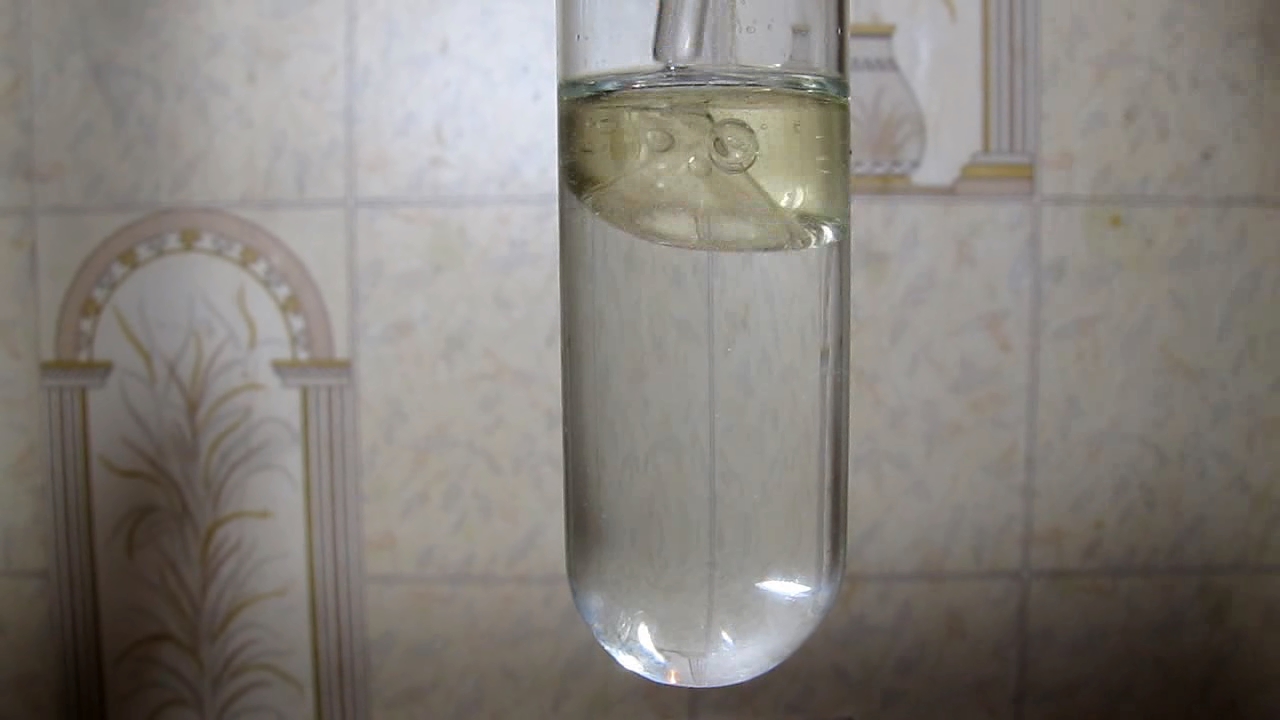

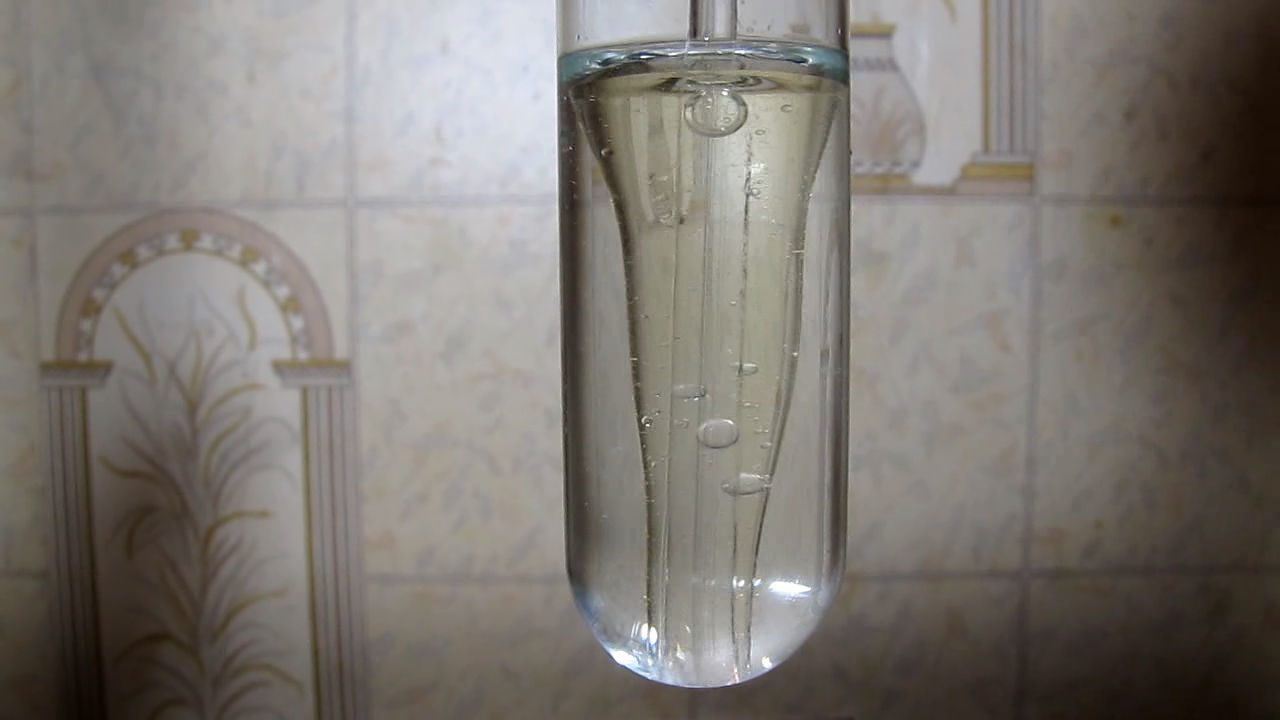

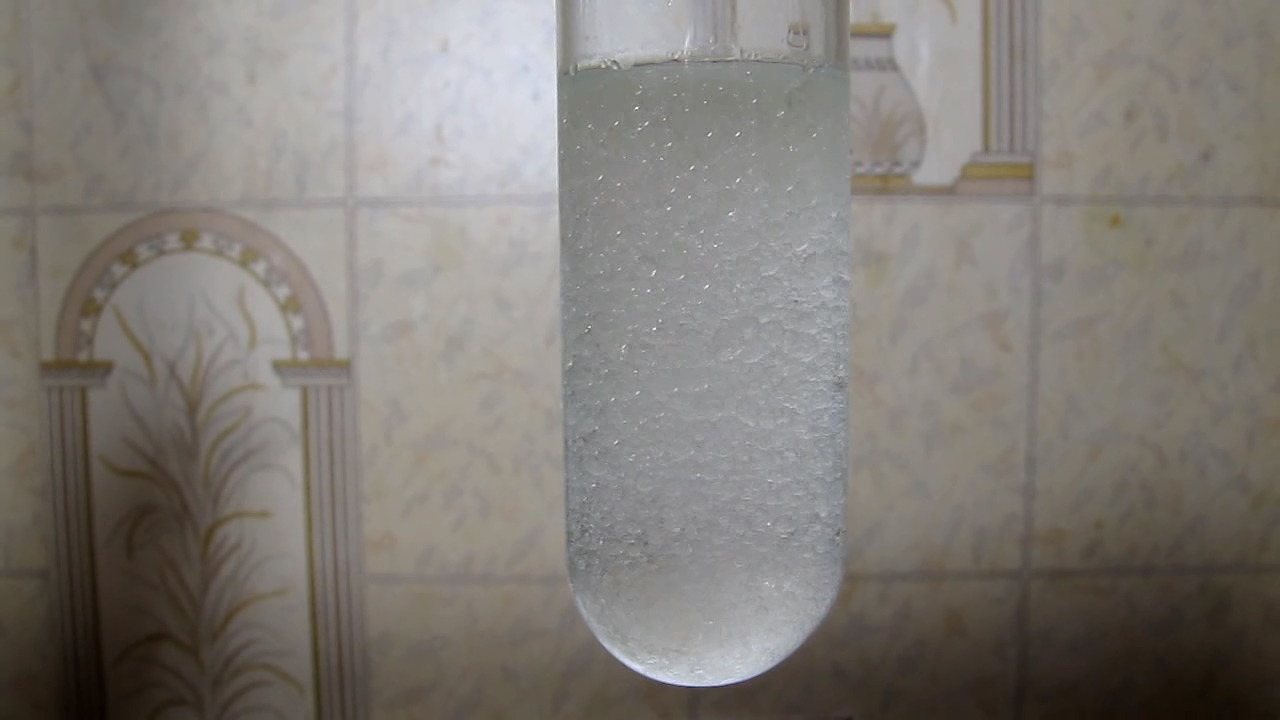

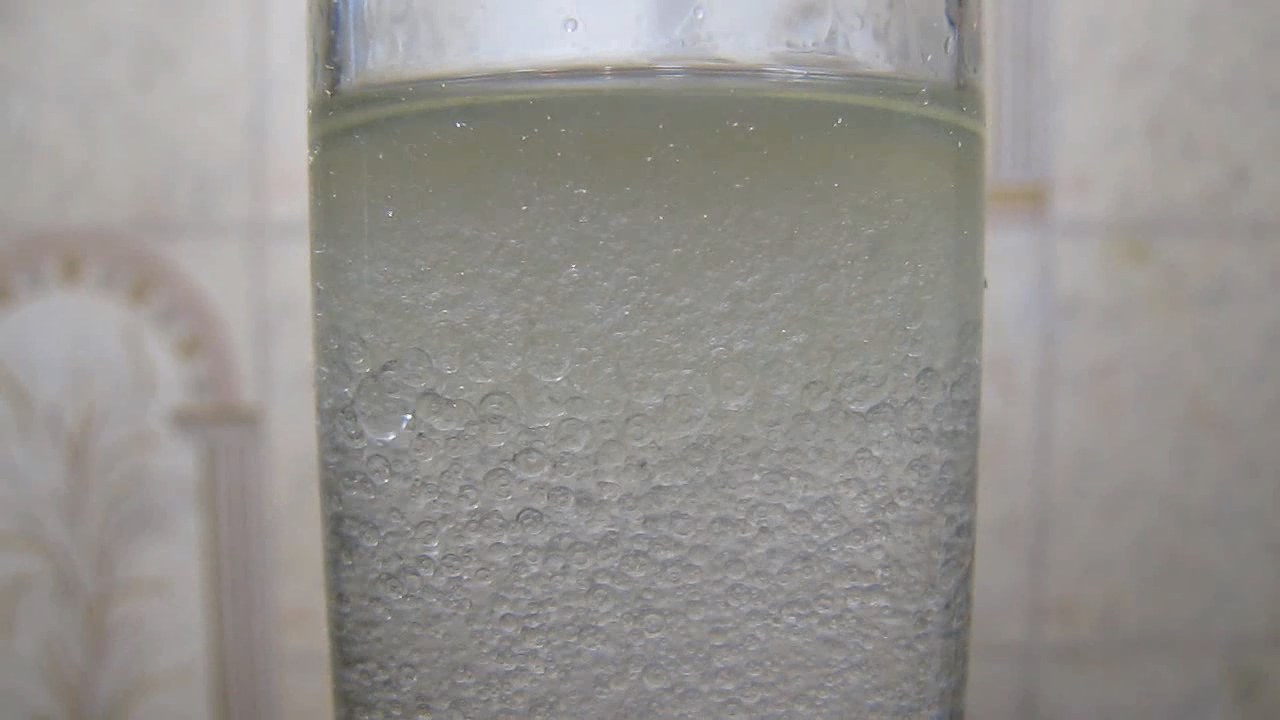

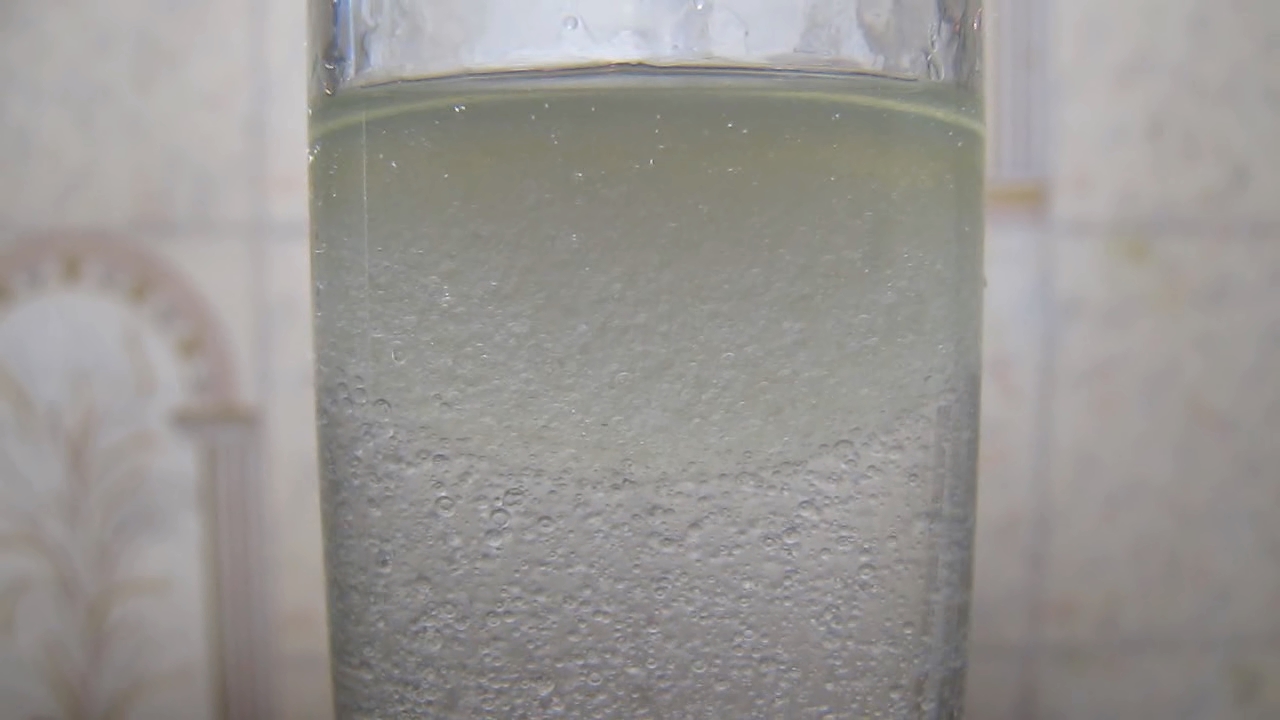

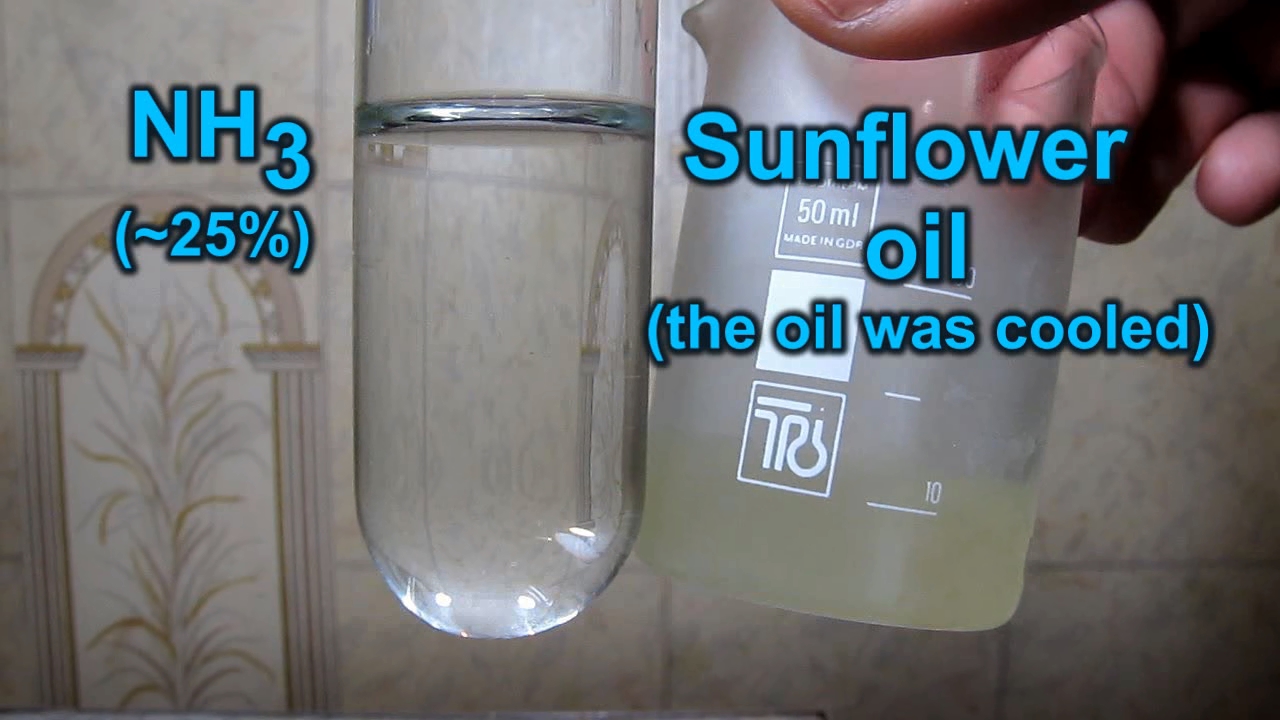

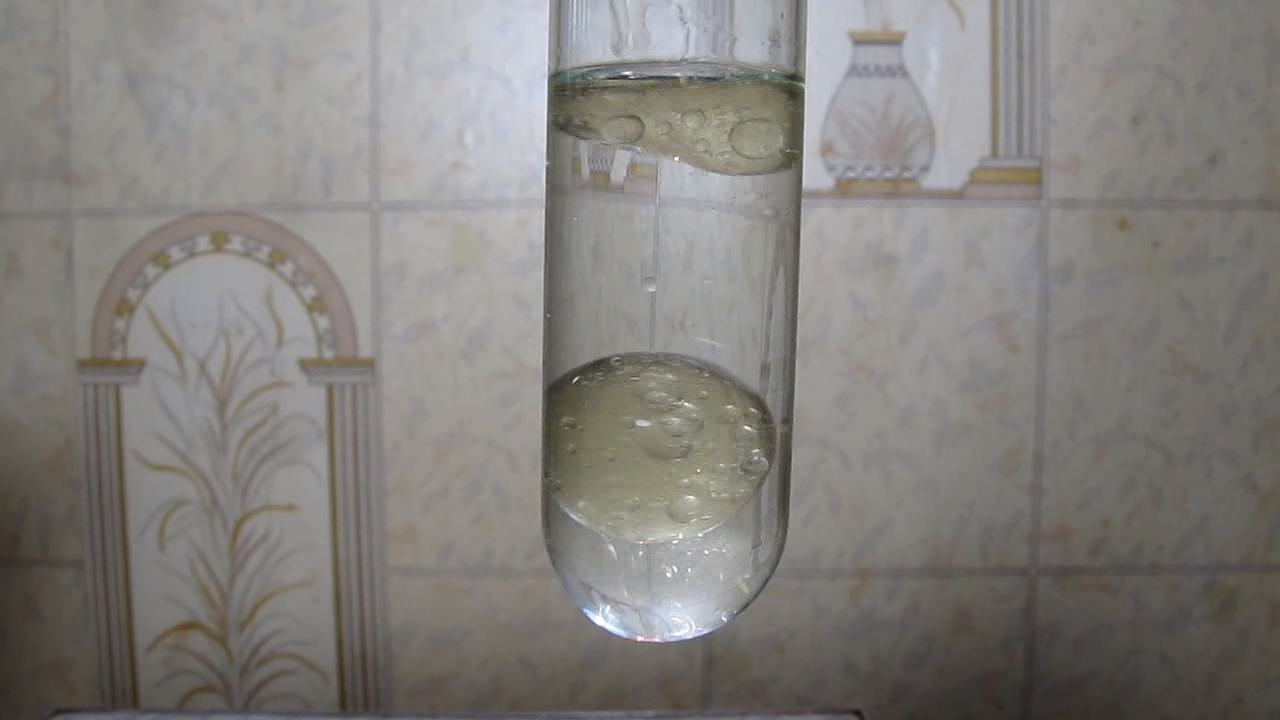

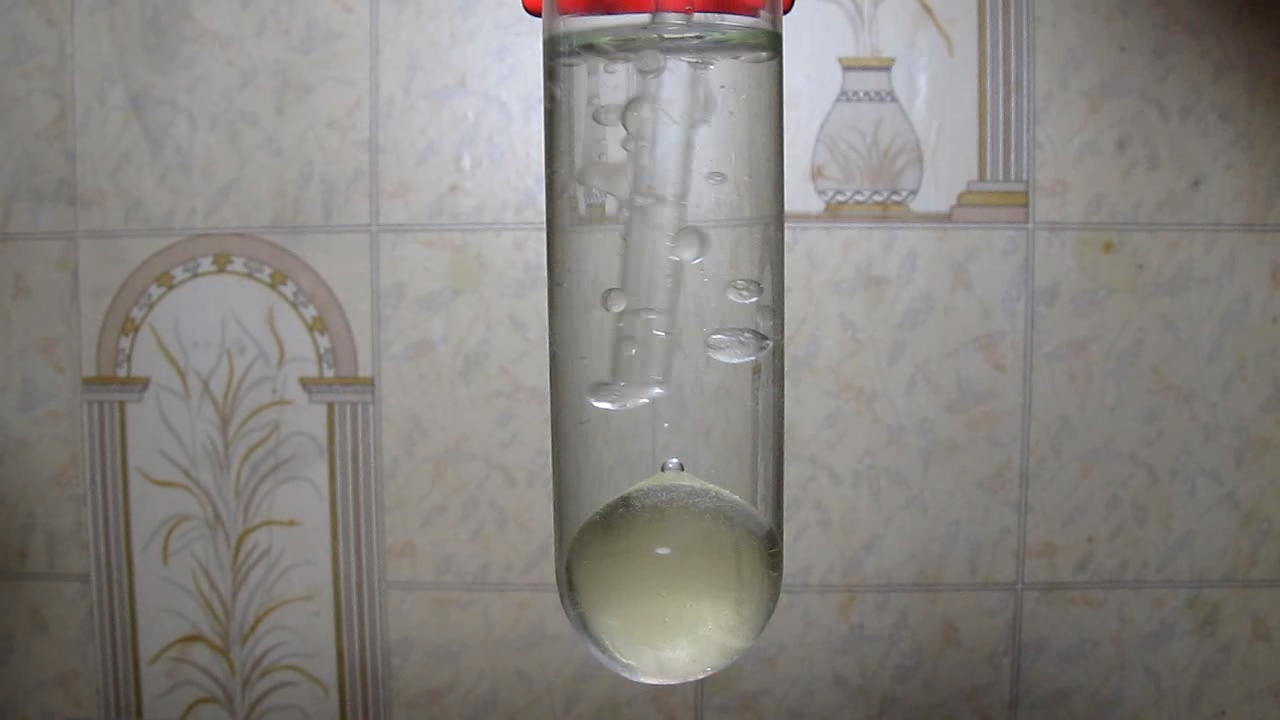

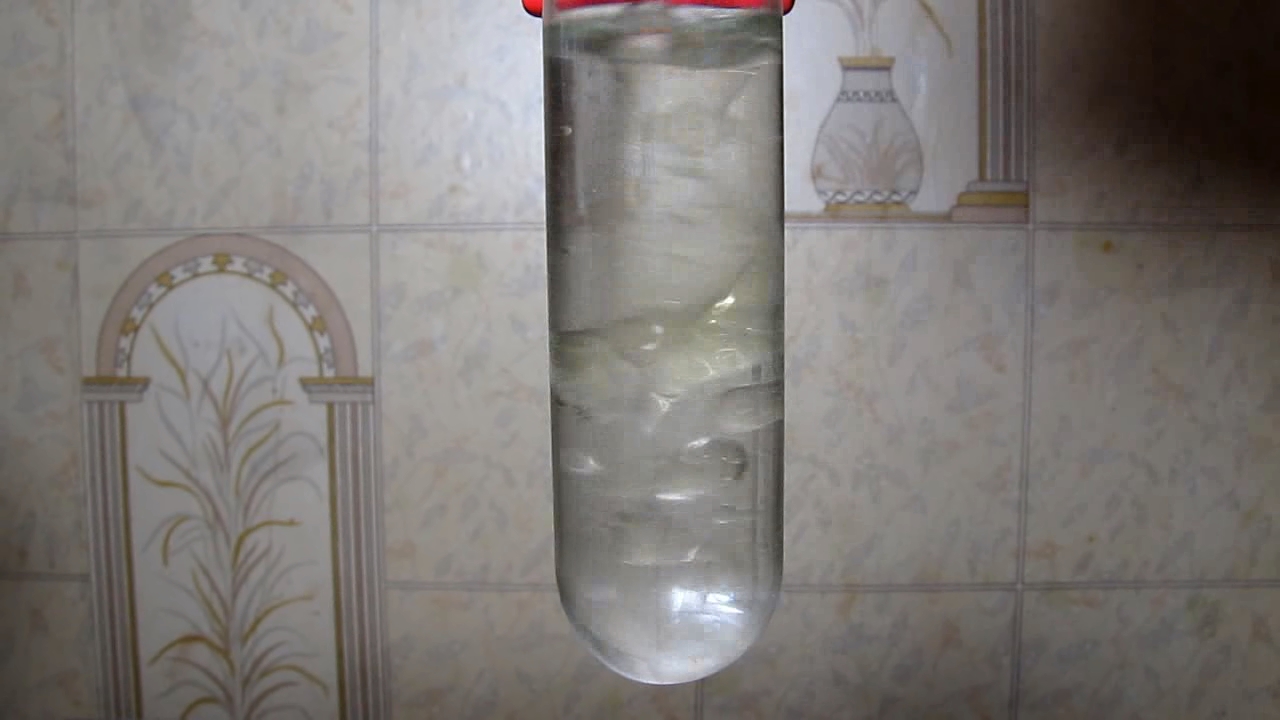

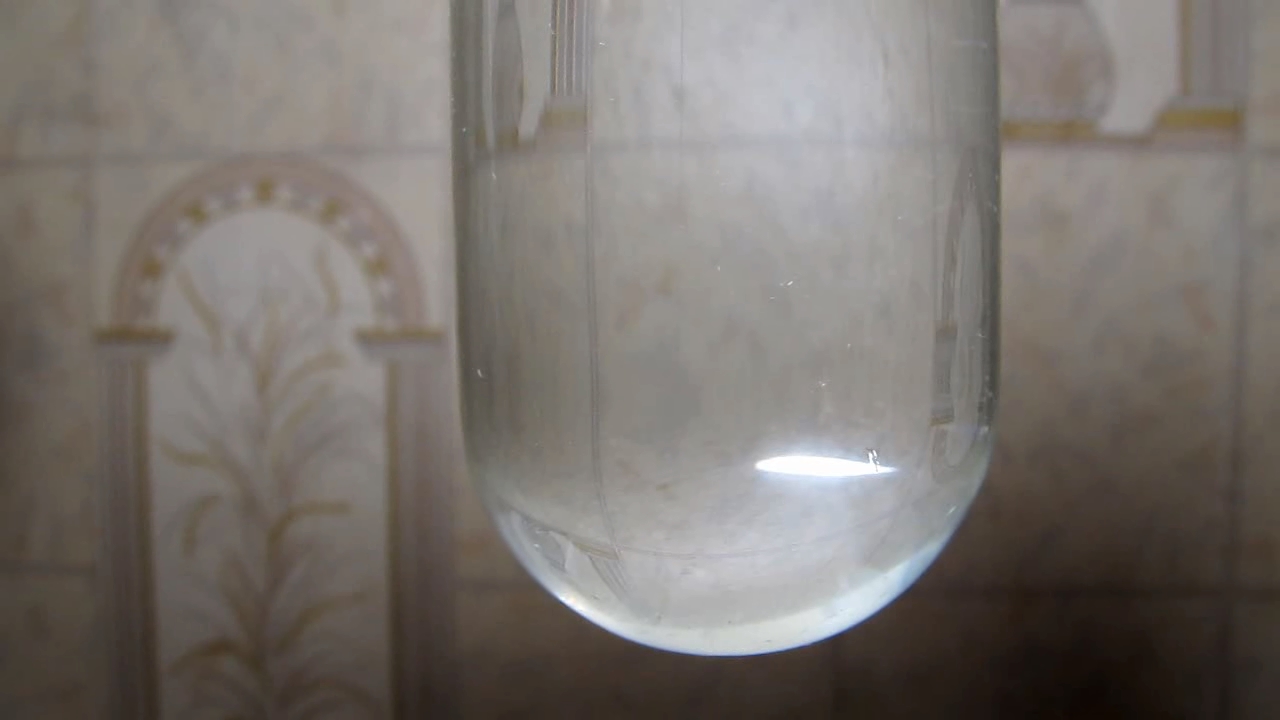

For example, ethyl or isopropyl alcohol can be added to an ammonia solution. These alcohols will reduce the density of the solution. However, this effect can be achieved by adding the alcohols to pure water. It is not necessary to use an ammonia solution for this purpose. It is possible to saturate the ammonia solution with ammonia gas while cooling. This is a good idea from a chemical point of view, but from a practical point of view, not really. A well-equipped laboratory is not yet available, and it is not wise to work with ammonia gas in my kitchen. Such works are possible but will not be pleasant. Another idea came up. As you know, the density of liquids depends not only on their chemical composition but also on temperature. In most cases, when a liquid is cooled, the density increases. Therefore, I can place a glass with sunflower oil in the freezer of the refrigerator! After cooling, quickly pipette the oil and pour it into the ammonia solution. I expected the cooled sunflower oil to sink at first because its density would be higher than the density of the ammonia solution. At the bottom, the oil would heat up, its density would increase, and the oil would float up. Of course, I need to pipette oil and add it to the test tube quickly so that sunflower oil does not have time to heat up BEFORE adding it to the ammonia solution. So, I placed a glass with sunflower oil (along with a pipette) in the freezer, and after half an hour, I discovered that the clear oil had become cloudy. I have often observed this phenomenon when oil bottles were sold outside in frosty weather. Many people believe that the cloudiness of the oil occurs because unscrupulous sellers add some water to the oil, and the water freezes in the cold. This opinion is incorrect because the solubility of water in oil is very low. Also, if water is present in the oil, forming an emulsion, the oil will be cloudy even at room temperature. A colleague explained to me the reason why sunflower oil becomes cloudy during cooling. It turns out that this oil contains higher paraffin hydrocarbons. When cooled, they form a solid phase. It is difficult to separate these hydrocarbons, and they do not degrade the quality of the oil, so everything is left as is. By the way, other vegetable oils (not just sunflower oil) also become cloudy in the cold. Solid paraffin hydrocarbons did not interfere with the experiment either. However, the oil viscosity increased significantly after cooling, making it difficult to draw the oil into a pipette with a narrow mouth. So, I took another pipette with a wider mouth that had not been pre-cooled in the freezer. I drew the cold oil with the pipette and found that the cloudiness disappeared. This meant the oil was warming up, and the solid hydrocarbons had dissolved again [K1]. I quickly added cold sunflower oil to the ammonia solution. The drops sank into the solution, forming balls. Some of the balls sank to the bottom, and some surfaced. At the bottom, drops of oil combined into a large ball. The drops that floated to the surface formed a top layer of oil with a strongly convex bottom surface (like a magnifying glass lying on a table). The subsequent portions of the oil always rose, combining with the top layer. During the addition, the oil had time to warm up, resulting in a decrease in density; therefore, the sunflower oil no longer sank in the aqueous ammonia. I tried to immerse the top layer of oil into the solution, pressing lightly on it with a glass rod. The result was the opposite: due to shocks in the liquid, the lower layer of oil came off the bottom and floated to the surface, combining with the upper layer. The temperature of the oil at the bottom became equal to the temperature of the ammonia solution, so this oil also floated to the surface. I continued trying to 'drown' the oil with a glass rod. Once it was successful - a big ball of sunflower oil temporarily sank to the bottom. I decided to redo the experiment, slightly changing the technique. I placed a wide-mouth pipette in a glass with sunflower oil, having previously filled the pipette with oil. I put the glass in the freezer to cool. I took a new test tube with a concentrated ammonia solution. When the oil in the freezer had cooled down, I took the pipette and quickly added the contents into the ammonia solution (without giving time for the oil to warm up in the air). At first, the white and turbid oil collected near the surface of the solution but then formed a huge drop that sank to the bottom. I added the next portion of cold oil - and the same thing happened. However, not all of the oil sank - a small part remained floating on the surface of the solution. In the ammonia solution, the oil warmed up and restored its original appearance. The white and cloudy liquid became yellow, almost not turbid, since the solid paraffin hydrocarbons had dissolved again. However, the oil did not float to the surface of the ammonia solution after warming to room temperature, instead forming the bottom layer. Minutes passed, and the oil remained at the bottom. According to Archimedes' principle, the oil should float to the surface under the influence of buoyant force since the density of sunflower oil was now lower than that of the surrounding ammonia solution. It turns out that the oil should not float up. The buoyant force (Archimedes' force) acts on objects partially or fully immersed in a liquid. However, if there is no liquid beneath the object, only the bottom of a vessel, the buoyant force does not act on such object. The opposite phenomenon is observed - a hydrostatic pressure presses the object to the bottom [2]. Another force that kept the oil at the bottom was the adhesion of the oil to the glass of the test tube. Time passed, but the oil did not want to float - what a shame! I tapped the test tube with my finger - the oil did not surface. I tried warming the bottom of the test tube with my palm - that did not help either. The oil must be separated from the test tube's bottom to float. To do this, I immersed a glass rod in the ammonia solution and rotated it carefully over the oil layer. After several attempts, the oil formed a large ball and slowly rose to the surface. Upon reaching the surface of the ammonia solution, the ball turned into a top oil layer. Some of the oil remained at the bottom, but I also made it float with the glass rod. I mixed the contents of the test tube. The oil layer turned into droplets, which were dispersed in the ammonia solution. After the mixing stopped, the droplets quickly floated to the surface and merged, forming the top layer of oil. After a day, the ammonia layer became transparent and colourless (without turbidity), but the oil layer remained white and opaque. After a week, the oil layer remained opaque. Cloudiness of the sunflower oil can be explained by the formation of a 'water-in-oil' emulsion, but such an emulsion should gradually break down without stabilizers. Even before conducting a literature search, I concluded that the white colour of sunflower oil is due to a chemical reaction. To explain the train of thought, I will give a few facts. As you know, vegetable and animal fats consist mainly of triglycerides of higher fatty acids (esters of higher fatty acids and glycerol). When fats interact with aqueous solutions of sodium (potassium) hydroxide or carbonates of these metals, a chemical reaction occurs called 'saponification'. As a result, glycerol as well as sodium (potassium) salts of fatty acids form, which are called soaps. That is right - good old soap is formed. This process has been known for many centuries; it was used for making soap in ancient times. A recipe for making soap was found on a Sumerian clay tablet around 2500 BC. Nowadays, many other substances and their mixtures have appeared that are sold under the name 'soap', but 'traditional' soaps obtained from fats and alkalis have not lost their importance. What happens if you use an aqueous solution of ammonia instead of sodium hydroxide? How will it react with fats? Is ammonium soap formed instead of sodium soap? If the answer is 'yes', then it is clear why sunflower oil turned white and opaque when interacting with a concentrated ammonia solution. Let us try to answer the questions raised. Sodium hydroxide and potassium hydroxide are strong bases, while higher fatty acids are weak acids. Accordingly, sodium (potassium) salts of higher fatty acids undergo hydrolysis in an aqueous solution, as a result of which the solution becomes alkaline. Let me emphasize that hydrolysis, in this case, is only partial. These salts are quite stable. On the other hand, salts of weak bases and weak acids readily undergo hydrolysis in an aqueous solution (the degree of hydrolysis is high). In some cases, hydrolysis of such salt occurs completely, making it impossible to obtain this salt from the solution. For example, silicic acid is weak. Sodium hydroxide, as we have already noted, is a strong base. An aqueous solution of ammonia is a weak base. This determines the stability of corresponding salts. Sodium silicate is a well-known and readily available compound. More precisely, many different sodium silicates are known; the formula of their mixture is simplified as Na2SiO3. In an aqueous solution, this substance is partially hydrolyzed, consequently; a solution of sodium silicate is alkaline. Unlike the previous case, when trying to obtain ammonium silicate (NH4)2SiO3, for example, by an exchange reaction between ammonium sulfate and sodium silicate, you will get silicic acid and ammonia instead of ammonium silicate since this compound is completely decomposed by water. Na2SiO3 + (NH4)2SO4 = Na2SO4 + 2NH3 + [H2SiO3]* *xSiO2·yH2O A similar attempt to obtain aluminium sulfide in an aqueous solution leads to the formation of hydrogen sulfide and aluminium hydroxide. 2AlCl3 + 3Na2S + 6H2O = 2Al(OH)3 + 3H2S + 6NaCl Note that aluminium sulfide can be easily obtained by heating aluminium and sulfur powders. This reaction is accompanied by combustion. 2Al + 3S = Al2S3 Solid aluminium sulfide is stable unless it comes into contact with water. When water is added, rapid hydrolysis of aluminium sulfide occurs with the release of gaseous hydrogen sulfide. In the case of chromium(III) sulfide, things become even more interesting. Attempts to obtain this compound in an aqueous solution (for example, through the reaction of chromium(III) sulfate and sodium sulfide) result in the formation of chromium hydroxide and hydrogen sulfide. Chromium (III) behaves similarly to aluminium in this reaction. However, chromium sulfide, synthesized by heating chromium and sulfur, exhibits resistance to water. What about ammonium salts of higher fatty acids? Do they exist? It is possible that ammonium soaps do not exist because they are decomposed by water; is this assumption correct? I found information on this topic. It turns out that ammonium soaps exist and are used as herbicides. These compounds are formed in the reaction of fatty acids with an aqueous solution of ammonia. However, when the solution is evaporated, ammonium soaps decompose into ammonia and fatty acids. As an example, below is a quote from the patent: 'Ammonium soaps are usually made by reaction of a solution of ammonium hydroxide with a fatty acid. The ammonium hydroxide is diluted with water. To this hot water ammonium hydroxide solution is added the molten fatty acid. Soaps made by this process result in paste products having 20 to 75% solids as ammonium soaps. It is well known in the art that the removal of water by standard practices would result in the decomposition of the salt into the fatty acid and ammonia gas which would be lost during the removal of the water. (United States Patent P 3,053,867 - Anhydrous ammonium soap)' If fatty acids react with ammonia, then the triglycerides of fatty acids that are contained in sunflower oil will also react. Thus, the change in the appearance of sunflower oil in an aqueous ammonia solution is due to the saponification reaction. Photos/Video __________________________________________________ 2 Nowadays, anyone can find many scientific and educational videos at any convenient time. It was different during my childhood. There were no computers and the Internet available then. Educational films and programs were shown on television, but not often. For example, sometimes you could watch physics lessons. Then, these lessons were too complicated for me, but I had to watch them because there was no alternative. During one of these lessons, an interesting exercise on physics was given, the solution of which was explained by the outstanding teacher K.V. Corsac (К.В. Корсак). At the bottom of an aquarium with water is a paraffin wax block in the shape of a rectangular parallelepiped with the following dimensions (...). Calculate the magnitude of the force that acts on the block. The exercise had a trick. Many students would calculate the buoyant force that pushes the block to the water's surface. But, there is no water under the block, so the paraffin wax will not float. On the contrary, the hydrostatic pressure of the water will press the paraffin wax to the bottom. In this case, the material of the block does not matter since the pressure force of the water does not depend on the density of this material. There must be no water between the block and the bottom of the vessel. Sometimes, in the text of such exercise, they give the density of paraffin wax (which is not needed for the solution) to confuse students. A similar phenomenon was observed in the case of our sunflower oil. Сейчас найти научное и образовательное видео может любой желающий в любое удобное время. Во времена моего детства было иначе. Доступных компьютеров и интернета тогда не было. По телевидению показывали образовательные фильмы и передачи, только нечасто. Например, иногда можно было посмотреть уроки физики. Тогда для меня они были слишком сложными, но приходилось их смотреть, поскольку альтернатива отсутствовала. На одном из таких уроков я встретил интересную задачу по физике, решение которой объяснял выдающийся преподаватель К.В. Корсак. На дне аквариума с водой находится брусок парафина в форме прямоугольного параллелепипеда с такими-то размерами (...). Рассчитайте величину силы, которая действует на брусок. Задача была с подвохом. Многие ученики стали бы рассчитывать силу Архимеда, которая выталкивает брусок на поверхность. Но под бруском нет воды, поэтому парафин не будет всплывать. Наоборот, гидростатическое давление воды будет прижимать парафин ко дну. В данном случае материал бруска не имеет значения, так как сила давления воды не зависит от плотности этого материала. Важно, чтобы между бруском и дном сосуда не было воды. Иногда в тексте подобной задачи приводят величину плотности парафина (которая не нужна для решения), чтобы сбить учеников с толку. Подобное явление наблюдалось и в случае нашего масла. |

|

Подсолнечное масло и раствор аммиака - часть 2

Во время прошлого эксперимента не хватило немного удачи, чтобы наблюдать, как подсолнечное масло тонет в концентрированном водном растворе аммиака (~25% вес.). Для достижения такого результата нужно чуть увеличить плотность подсолнечного масла или чуть уменьшить плотность раствора аммиака, использованных для эксперимента.

Например, в раствор аммиака можно добавить этиловый или изопропиловый спирт. Это уменьшит плотность раствора. Однако, такого эффекта можно достичь и, добавляя спирты в чистую воду. Раствор аммиака для этой цели использовать не обязательно. Можно насытить раствор аммиака газообразным аммиаком при охлаждении. С химической точки зрения это хорошая идея, однако, исходя из практических соображений, - не совсем. Оснащенная лаборатория пока недоступна, а на моей кухне лучше не работать с газообразным аммиаком. Это не смертельно (от слова 'совсем'), но приятного будет мало. Возникла новая идея. Как известно, плотность жидкостей зависит не только от их химического состава, но и от температуры. В большинстве случаев при охлаждении плотность увеличивается. Раз так, то что мешает мне поместить стакан с подсолнечным маслом в морозильную камеру холодильника! После охлаждения быстро набрать масло пипеткой и вылить его в раствор аммиака. Я ожидал, что сначала охлажденное подсолнечное масло утонет, поскольку его плотность будет выше плотности раствора аммиака. На дне масло нагреется, его плотность увеличится и масло всплывет. Разумеется, набирать масло пикетной и добавлять его в пробирку нужно быстро, чтобы подсолнечное масло не успело нагреться ДО добавления его в раствор аммиака. Итак, поместил я стакан с подсолнечным маслом в морозильник (вместе с пипеткой), а через полчаса обнаружил, что прозрачное масло стало мутным. Данное явление я наблюдал много раз, когда бутылки с маслом продавали в морозную погоду за пределами помещения. Многие люди считают, что помутнение масла происходит из-за того, что недобросовестные продавцы добавляют в масло воду, а вода на морозе замерзает. Это мнение неверно, поскольку растворимость воды в масле очень низкая. А, если вода будет присутствовать в масле в виде эмульсии, масло будет мутным и при комнатной температуре. Причину помутнения подсолнечного масла при охлаждении мне объяснил коллега. Оказывается, данное масло содержит высшие парафиновые углеводороды. При охлаждении они образуют твердую фазу. Отделять эти углеводороды трудно и они не ухудшают качество масла, поэтому все оставляют, как есть. Кстати, на морозе становятся мутными и другие растительные масла (не только подсолнечное масло). Твердые парафины также не мешали нашему эксперименту. Однако, после охлаждения вязкость масла сильно увеличилась, в результате его было трудно набрать пипеткой с узким носиком. Я взял другую пипетку с более широким носиком, которая не была предварительно охлаждена в морозильнике. Набрал масло и обнаружил, что муть исчезла. Это означало, что масло нагревается и парафины снова растворились [K1]. Быстро добавил холодное подсолнечное масло в раствор аммиака. Капли погрузились в раствор, образуя шарики. Некоторые из шариков опустились на дно, некоторые всплыли. На дне капли масла объединились в большой шар. Капли, которые всплыли, образовали верхний слой масла с сильно выпуклой нижней поверхностью (как увеличительная линза, которая лежит на столе). Следующие порции масла всегда выплывали, объединяясь с верхним слоем. За время добавления масло успело нагреться (его плотность уменьшилась и подсолнечное масло уже не тонуло в водном аммиаке). Попробовал погрузить в раствор верхний слой масла, слегка надавливая на него стеклянной палочкой. Результат оказался противоположным: из-за толчков в жидкости нижний слой масла оторвался ото дна и всплыл, объединившись с верхним слоем. Температура масла на дне выровнялась с температурой раствора аммиака и это масло также всплыло. Продолжил попытки 'утопить' масло стеклянной палочкой. Один раз это удалось - крупный шар масла временно опустился на дно. Решил переделать эксперимент, немного изменив технику. Поместил пипетку с широким горлом в стакан с подсолнечным маслом, заранее наполнив пипетку маслом. Поставил стакан в морозилку охлаждаться. Взял новую пробирку с концентрированным раствором аммиака. Когда масло в морозилке остыло, взял пипетку и быстро выдавил содержимое в раствор аммиака (не давая времени, чтобы масло нагрелось на воздухе). Сначала бело-мутное масло собралось возле поверхности раствора, но потом образовало огромную каплю, которая опустилась на дно. Добавил следующую порцию холодного масла - с ней произошло то же самое. Правда, не все масло утонуло - небольшая часть осталась плавать на поверхности раствора. Находясь в растворе аммиака, масло нагрелось и восстановило свой первоначальный внешний вид. Белая и мутная жидкость стала желтой и почти немутной, поскольку твердые парафины опять растворились. Однако, нагретое до комнатной температуры масло НЕ всплывало на поверхность, образуя нижний слой. Шли минуты, а масло так и оставалось на дне. Но ведь под действием силы Архимеда масло должно всплыть на поверхность, поскольку теперь его плотность ниже, чем плотность окружающего раствора аммиака. Оказывается, масло и не должно всплывать. Сила Архимеда действует на тела, погруженные в жидкость частично или полностью. Однако, если под объектом нет жидкости, а только дно сосуда, сила Архимеда на такой объект не действует. Наблюдается обратное явление - гидростатическое давление прижимает объект ко дну [2]. Другая сила, которая удерживала масло внизу - адгезия масла к стеклу пробирки. Время шло, а масло не хотело всплывать - это уже какое-то безобразие. Постучал по пробирке пальцем - масло не всплыло. Пробовал греть низ пробирки ладонью - это тоже не помогло. Чтобы масло всплыло, его нужно отделить от дна. Для этого я погрузил в раствор аммиака стеклянную палочку и стал осторожно совершать круговые движения над маслом. После нескольких попыток масло образовало крупный шар, который медленно всплыл. Достигнув поверхности раствора аммиака, шар масла образовал верхний слой. Часть масла осталась на дне, но я также заставил ее всплыть с помощью палочки. Перемешал содержимое пробирки. Слой масла превратился в капельки, которые диспергировались в растворе аммиака. После прекращения перемешивания капли быстро всплыли и слились, образуя верхний слой масла. Через сутки слой аммиака стал прозрачным и бесцветным (без мути), зато слой масла остался белым и непрозрачным. Через неделю слой масла остался непрозрачным. Помутнение масла можно объяснить образованием эмульсии 'вода-в-масле', но такая эмульсия без стабилизаторов должна постепенно разрушаться. Еще до того, как провести поиск в литературе, я пришел к мнению, что белая окраска подсолнечного масла обусловлена химической реакцией. Чтобы объяснить ход мыслей, приведу несколько фактов. Общеизвестно, что растительные и животные жиры состоят в основном из триглицеридов высших жирных кислот (сложных эфиров высших жирных кислот и глицерина). При взаимодействии жиров с водным растворами гидроксида натрия (калия) или карбонатов этих металлов происходит химическая реакция, которая носит название 'реакция омыления'. В результате образуются глицерин и натриевые (калиевые) соли жирных кислот, которые называются мылами. Так и есть - образуется старое доброе мыло. Данный процесс известен многие века, его использовали для варки мыла еще в древности. Рецепт изготовления мыла был найден на шумерской глиняной табличке около 2500 г. до н.э. В наши времена появилось много других веществ и их смесей, которые продаются под названием 'мыло', но 'традиционные' мыла, полученные из жиров и щелочи, не потеряли своего значения. А что будет, если вместо гидроксида натрия использовать водный раствор аммиака? Как он будет реагировать с жирами? Образуется ли вместо натриевого мыла аммониевое? Если ответ "да", то понятно, почему подсолнечное масло стало белым и непрозрачным при действии концентрированного раствора аммиака. Попробуем ответить на поставленные вопросы. Гидроксид натрия и гидроксид калия - сильные основания, а высшие жирные кислоты - слабые кислоты. Соответственно, натриевые (калиевые) соли высших жирных кислот подвергаются гидролизу в водном растворе, в результате чего раствор приобретают щелочную реакцию. Подчеркну, гидролиз в данном случае лишь частичный. Указанные соли вполне стабильны. С другой стороны, соли слабых оснований и слабых кислот подвергаются гидролизу в водной среде гораздо сильнее. В некоторых случаях гидролиз таких солей происходит полностью, а это означает невозможность получить соответствующую соль из водного раствора. Например, кремниевая кислота слабая. Гидроксид натрия, как мы уже отмечали, сильное основание. Водный раствор аммиака - слабое основание. Это определяет устойчивость соответствующих солей. Силикат натрия - хорошо известное и легко доступное соединение. Точнее, разных силикатов натрия известно много, упрощенно формулу их смеси пишут как Na2SiO3. В водном растворе данное вещество частично гидролизуется, в результате раствор силиката натрия щелочной. В отличие от предыдущего случая, при попытке синтезировать силикат аммония (NH4)2SiO3, например, реакцией обмена между сульфатом аммония и силикатом натрия, вы получите кремниевую кислоту и аммиак вместо силиката аммония, поскольку данное вещество полностью разлагается водой. Na2SiO3 + (NH4) 2SO4 = Na2SO4 + 2NH3 + [H2SiO3]* *xSiO2·yH2O Аналогичная попытка получить в водном растворе сульфид алюминия приводит к образованию сероводорода и гидроксида алюминия. 2AlCl3 + 3Na2S + 6H2O = 2Al(OH) 3 + 3H2S + 6NaCl Обратите внимание, сульфид алюминия можно легко получить нагреванием порошков алюминия и серы. Реакция происходит со вспышкой. 2Al + 3S = Al2S3 Твердый сульфид алюминия устойчив, если он не контактирует с водой. При добавлении воды происходит быстрый гидролиз сульфида алюминия с выделением газообразного сероводорода. В случае сульфида хрома (III) все еще интереснее. Попытка получить данное вещество в водном растворе (например, реакцией сульфата хрома (III) и сульфида натрия) приводит к образованию гидроксида хрома и сероводорода. Хром (III) ведет себя аналогично алюминию. Однако, сульфид хрома, синтезированный нагреванием хрома и серы, устойчив к действию воды. А как обстоит дело с аммониевыми солями высших жирных кислот? Существуют ли они? Возможно, аммониевые мыла не существуют, поскольку они разлагаются водой, верно ли это допущение? Провел поиск. Оказывается, аммониевые мыла существуют и применяются в качестве гербицидов. Данные соединения образуются в результате реакции жирных кислот с водным раствором аммиака. Однако, при упаривании раствора аммониевые мыла разлагаются на аммиак и жирные кислоты. Для примера приведу цитату из патента: 'Аммиачное мыло обычно получают путем реакции раствора гидроксида аммония с жирной кислотой. Гидроксид аммония разбавляют водой. К этому горячему водному раствору гидроксида аммония добавляют расплавленную жирную кислоту. Мыло, полученное данным способом, представляет собой пастообразные продукты, содержащие от 20 до 75% твердых веществ в виде аммиачного мыла. В данной области производства хорошо известно, что удаление воды стандартными методами приведет к разложению соли на жирную кислоту и газообразный аммиак, который будет потерян при удалении воды. (Патент США P 3053867 - Безводное аммиачное мыло)' 'Ammonium soaps are usually made by reaction of a solution of ammonium hydroxide with a fatty acid. The ammonium hydroxide is diluted with water. To this hot water ammonium hydroxide solution is added the molten fatty acid. Soaps made by this process result in paste products having 20 to 75% solids as ammonium soaps. It is well known in the art that the removal of water by standard practices would result in the decomposition of the salt into the fatty acid and ammonia gas which would be lost during the removal of the water. (United States Patent P 3,053,867 - Anhydrous ammonium soap)' Если жирные кислоты реагируют с аммиаком, значит будут реагировать и триглицериды жирных кислот, из которых состоит подсолнечное масло. Таким образом, изменение внешнего вида подсолнечного масла в водном растворе аммиака обусловлено реакцией омыления. |

Cooled sunflower oil and ammonia solution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Комментарии

К1

By the way, olive oil does solidify not only in the freezer, but also in the refrigerator near zero Celcias. In this way it was proposed to determine the authenticity of olive oil. However, today there are many varieties of olive oil on sale of different quality and obtained using different technologies.

Кстати, оливковое масло застывает даже не в морозилке, а просто в холодильнике около нуля. Таким способом предлагалось определять подлинность оливкового масла. Правда, нынче в продаже есть много разновидностей оливкового масла разного качества и полученных по разным технологиям. |